- 280 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

A volume of collected papers by one of the most prominent thinkers on psychoanalytic processes in organisations. The papers in this collection span two-and-a-half decades and address some of the most difficult, complex, and paradoxical aspects of the human condition.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

Topic

PsychologieCHAPTER ONE

Thinking refracted

Groups and thinking

Groups of human beings can be tyrannous, or benign. They are, pre-eminently, the loci of experience. It is experience that gives rise to feelings/emotions, which activate our thinking. Thinking is the capacity of human beings to engage with their world. Thinking depends on our ability to experience our experiences as opposed to merely perceiving them as events or happenings that occur, whose import never engages us emotionally.

Thinking I am to liken as a metaphor to light falling on a prism, which is then refracted into colour (wavelengths) on leaving the prism. Furthermore—and here I am beholden to Wilfred Bion—thinking and thought exist in search of a thinker. The thinker catches the thought and breaks it down into its constituents with which the thinker proceeds to “play”, creating new thinking and thoughts. The metaphor reaches its limits because thinking is not tangible like light.

I want, at the same time, to capture the idea that thinking can also arise from a thinker. It is as if the prism were initiating light from inside itself, which is then refracted through the prism. Thinking I regard as a two-way interactive process; it can be begun from either the outside or the inside of the individual. How else does one explain the inventiveness of an Einstein, who creates a totally new way of construing the world through quantum mechanics, with incalculable effects on thinking about the natural world in our own century? How else does one explain the work of a poet who captures in a telling image the feeling/emotion that a particular experience evokes, causing the reader to look at similar experiences in a totally new way?

While it is possible for individuals to give added value to what has been thought in the past through the quality of their new thinking, I am persuaded that most thinking arises from the context that we inhabit. The idea of “refraction” I will stay with as a metaphor because it captures the notion that thinking is a wave function that goes on all the time, to be realized on occasion as a particle function that consists of actual thoughts, which human beings can then transact. Thinking can be conceptualized as being either a wave or a particle. One can “measure” it (identify its qualities) either in one form or the other, but not at the same time.

This flux of thinking is experienced in groups. Without the experiences of taking part in groups we would be ignorant, or not conscious, of the ill-defined—possibly indefinable—oppositions between: creativity and destruction; chaos and cosmos; the sacred and the profane; immanence and transcendence; love and hate; joy and despair; the life-giving and anti-life tendencies; Eros and Thanatos; ruthlessness and ruth (concern); good and evil; knowing and unknowing; the finite and the infinite; the conscious and the unconscious; integration and disintegration; together with all the other interactive polarities that are necessary conditions for knowing and understanding, which are the quintessence of being a human being. In this long sentence I attempt to capture and express the continuous bombardment on our senses of knowing, and not knowing, that we come to experience in relation to other people in groups. Sometimes the thinking is a wave; at other times it freezes, or coagulates, into a particle.

Group life, no matter how small the configuration, is essential for our survival as a species. We learn to think by responding with our feelings to our experiences in relationships and groups, or in no-relationships or no-groups. The absence of a relationship, or group, can be a powerful experience, resulting in feelings and emotions. Ranging from our very first experiences of relating to mother, or mother-substitute, by whom we are inducted into speech, language, and culture, through to the groups and groupings we belong to as a child, as an adolescent, and as an adult, we face or confront the issues raised by the complexity of living. Thinking, coupled with the ability to use language to communicate, is what distinguishes human beings from any other animals. (Dolphins, for example, can think, but they have a different means of communication.) Thinking is integral to our humanity, but is so routine that it is difficult to comprehend how essential it is for us as humans.

All organizations, as I shall say throughout the following chapters, rely on the thinking of the people who take up roles within them. Without thinking, there would be no organization. Thinking is a defining characteristic of the life and work of the people in an organization. And the same can be said for any other social configuration.

One psychoanalyst who devoted his intellectual life to the study of thinking, thought, and knowing and how these are arrived at was Wilfred Bion. In his Introduction to Experiences in Groups (1961), he writes:

I am impressed, as a practising psycho-analyst, by the fact that the psycho-analytic approach, through the individual and the approach that these papers describe, through the group, are dealing with different facets of the same phenomena. The two methods provide the practitioner with a rudimentary binocular vision. The observations tend to fall into two categories, whose affinity is shown by phenomena which, when examined by one method, centre on the Oedipal situation, related to the pairing group, and when examined by the other, centre on the sphinx, related to problems of knowledge and scientific method. [Bion, 1961, p. 8, italics added]

Bion was using the myth of the riddle of the Sphinx to express the capability of human beings to ask questions of themselves about their existence and its meaning, which is the basis of knowing and knowledge. The private, personal Oedipal myth, which had been used by Freud to found psychoanalysis, Bion regarded as an “integral part of the human mind... that allows the young child to make real contact with his parents” (Bléandonu, 1994, p. 185).

This inherent thrust for fundamental knowledge of self in relation to the environment, this epistemophilic instinct (Klein, 1921, 1928), is what makes us human, though it will be impeded by anxieties and fears and rests at the root of all that we know of the world in which we live. It is the basis of knowledge of—or, rather, our personal knowing of—the world and our place in it. In the context of groups, this exploration into their own lives is represented by the riddle of the Sphinx. As Hanna Biran puts it, the person who takes part in the explorations of a group and its life is exploring

a hidden world long gone and forgotten, which survives in the form of myths leaving behind some traces and signs, which are in fact powerful enough to compel us to inquire into the meaning of our lives.[Biran, 1997, p. 32]

Bion makes the differentiation, when referring to Freud’s division between ego instincts and sexual ones, by advocating that in thinking of groups a better distinction would be “between narcissism on the one hand, and what I shall call socialism on the other” (Bion, 1992, p. 105). [At another point in his text, he writes the term as “social-ism”, which captures the root idea. This spelling of the word rids it from its associations with ideologies such as Marxism and political movements like communism.] Here Bion is drawing a distinction between the instincts that are mobilized for the fulfilment of the individual’s life as such and the instincts that are brought into being when the political, communal features of life are pre-eminent, which are about knowledge and understanding—that is, the shared concerns and preoccupations of peoples as a totality. What can be mobilized against this understanding is psychosis, which is based on a hatred of reality. Psychosis, to which all human beings are prone, is the process whereby humans defend themselves from understanding the meaning and significance of reality, because they regard such knowing as painful. To do this, they use aspects of their mental functioning to destroy, in various degrees, the very process of thinking that would put them in touch with reality. As Iris Murdoch once said in an interview, “The great task in life is to find reality”, having already made the point that we settle for illusion and fantasy. T. S. Eliot anticipated this when he wrote in Burnt Norton, in effect, that human beings cannot tolerate too much reality (Lines 42/43). The only way the group member can preserve his/her narcissism (the sense of being an individual) is to destroy common sense, or sense of group pressure, by not becoming available for any kind of understanding of the nature of external reality, through working hypotheses (or interpretation).

This can be experienced at first hand in the context of groups. As I have said, Bion makes the key, fundamental observation that we can interpret the phenomena that occur in a group from two perspectives (binocular vision): that of Oedipus and that of Sphinx. The latter is concerned with the “social-istic”, political preoccupation, which is that of knowledge and understanding of us, as a common concern, giving meaning to our existence, or being, finding answers to the basic puzzles of what it is to be human. The significance of the “social-ism” (human beings are group animals) is that it leads to, for instance, the development of economics, religions, political institutions, and psychology. Individuals, each with her/his Oedipus, so to speak, think about common concerns and try to find ways of living together by setting guidelines, or laws, or rules, or principles.

Thought products

We use the word “thinking” in everyday speech. It refers to the activities of reasoning, imagining, and remembering. Here I am concerned with thinking in its widest sense, encompassing fantasy and phantasy, the processes of imagining, dreaming, and dream-work, both awake and sleeping, reasoning and problem solving. The end products of thinking are “thought products”, such as “poetry and novels, painting and plays, scientific theories and inventions” (McKellar, 1968, p. 77). My focus in this book is on groups and organizations, which I also see as “thought products”. In the case of groups, the people participating in them create a narrative that makes sense to them.

Similarly an organization is a narrative, which, in the case of, say, the Shell International Petroleum Company, may stretch over decades. As new employees are inducted into the company, they are introduced to the thinking and thought process of the organization. As these role holders rise in the organization, they may alter the thinking and so change the “thought product” and the ongoing narrative of the company. When the Planning Group was able to predict perestroika, the company was able to change its strategic direction. The thinking from the Planning Group altered the nature of the narrative, which changed the “thought product” that is Shell International (Schwartz, 1991).

Whereas a novel or play or painting is a fixed, tangible “thought product” when completed, a group or a company is a continuous, unfolding one. The dynamic that is associated with a group or organization makes it such that one might rather call it a “thinking product” in order to capture the present continuous feeling of how it continually transforms itself. How this dynamic arises I shall try to disentangle.

Forms of thinking

Pursuing the project of Sphinx, my working hypothesis is that there are four forms of thinking, each with its distinguishing subject area. To be sure, these four forms have been thought about previously. All of us, as we participate in groups and groupings, have the possibility of thinking about them afresh for ourselves, even though we know that we shall never achieve truth and that what we think, in the present, may well have been thought about before by someone at some time.

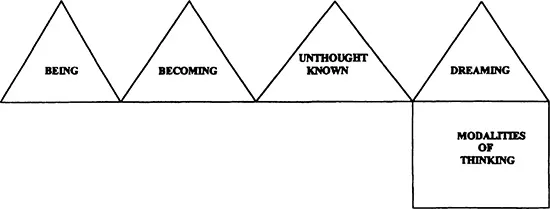

These four forms can be viewed as a four-sided pyramid. Thus we have the sense of refracted thinking, for knowledge, derived from experience, is not a body of thinking “out there” that has to be acquired through learning; it is, rather, both out there and in here. In a sense, we “make”, or construct, knowledge through thinking in our inner world of the mind.

The base of the pyramid, which will be a square, can be allotted to the modality of communication. A written text will be different from a dialogue or conversation, or a play, or a novel. The quality of the thinking will be different as it relies on different modalities, which will alter the content of thinking. (See Figure 1.1.)

Figure 1.1

There is, it can be hypothesized: (1) thinking as being; (2) thinking as becoming; (3) thinking as Dreaming; and (4) thinking as the “Unthought Known” (Bollas, 1987, 1989).

1.Thinking as being is all the thought that has ever been thought and is to do with existing, living, in the world as it is perceived. The substance of this knowledge generated by this type of thinking is the working resolution to the fundamental puzzles of existing, or being, in the world and, I suggest, underlies all architecture, philosophy, ethics, arts, literature, the sciences, and what we know of history, which, in a sense, is continually being re-discovered. There is a real sense in which this approximates the tacit knowledge to which Michael Polanyi refers.

There is the stream of consciousness with which we are intimately bound up, for it is an expression of how we are continually monitoring the experience of events and happenings as they occur. How we construe this depends on the form of our thinking and on the state of our mental life, which I will argue below, under the headings of modalities and psychic structure. As we think in the present tense, we are inevitably caught up in thought in the past tense and in the future tense, but the idea of tense, with its rules, is the product of thinking. In groups and groupings one can see this. Organizations would not continue to exist if we did not have access to that thinking which we do practically every second of our lives. Experiencing–feeling–thinking is the process essential to our consciousness and our being.

2.THINKING as becoming is the thinking we engage with as we attempt to alter our state of being. If you will, it is always concerned with the future and arises from a sense of frustration—of wanting things to be different—and from a sense of destiny. To be sure, although I have separated out these two forms of thinking, they interpenetrate each other. As I think of being, I am always thinking of how reality could become. All the advances in the natural sciences, all the creativity associated with the arts of all kinds, have their roots in becoming.

Imagine the world of business: while businesses can continue as they have in the past, they are always in a state of transition as they transform themselves from what they are into what they are in the process of becoming. In business, for example, we bring markets into being. Markets exist because they have been thought of, but new markets always have to be brought into being. The business environment today exists in the world of information technology, in a global environment, and is in a state of increasingly instant communication. We can have the working hypothesis that the corporate environment is to be “brought into being” by the participation of managers in the environment as an ecosystem.

Anita Roddick brought into being a market of women who bought her beauty products because they came from natural resources and were not tested on animals. Consequently, all the traditional suppliers of similar products had to re-think their market share and had to change accordingly. But it took one woman to see the potential market.

Pursuing the idea of thinking as becoming, managers, in particular, have the task of experiencing as directly as possible the business as-a-series-of-events-in-its-environment, through participating in bringing them into being and interpreting the resultant experiences mutatively. (I am using the term “mutatively” to give the sense that interpretation itself leads to new insights and understanding, which, in turn, alters the original interpretation. This is the idea behind the working hypothesis that I will use repeatedly throughout this text, which is that we can only give an approximation of what reality might be. A working hypothesis generates, or stimulates, other working hypotheses from other people as a way of building up as true a picture as possible of what the “truth might be”, accepting that we cannot know absolute truth.)

The distinction between thinking as being and thinking as becoming is difficult, but not impossible, to discern. The edges around these two forms are fuzzy, in reality. I believe that the concept of future is a useful distinguishing mark. In organizations, when the people in the company start to plan the future, we can see the separation of what the company does now and what the company could become. For example, we can build scenarios of the future, hold these in mind, and alter the company’s state of being to fit the nature of reality that is emerging.

Both thinking as being and thinking as becoming are in consciousness, but they do have their origins also in the infinite aspects of mind. They are constructions of what reality is experienced as being and what it could become. As constructions, they owe part of their origin to the Oedipal aspects of the human being in that they are construed through processes of the psyche. Reality is made from the inside world of the individual and exists because of inters...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Dedication

- Acknowledgements

- Contents

- Foreword

- Introuduction

- 1 Thinking refracted

- 2 The management of oneself in role

- 3 Exploring the boundaries of the possible

- 4 Signals of transcendence

- 5 The fifth basic assumption

- 6 Beyond the frames

- 7 Emergent themes for group relations in chaotic times

- 8 The politics of salvation and revelation in the practice of consultancy

- 9 To surprise the soul

- 10 Psychic and political relatedness in organizations

- 11 Tragedy: private trouble or public issue?

- References

- Index

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Tongued with Fire by W. Gordon Lawrence in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Psychologie & Geschichte & Theorie in der Psychologie. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.