- 200 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

In an age of virtual offices, urban flight, and planned gated communities, are cities becoming obsolete? In this passionate manifesto, Moshe Safdie argues that as crucibles for creative, social, and political interaction, vital cities are an organic and necessary part of human civilization. If we are to rescue them from dispersal and decay, we must first revise our definition of what constitutes a city.Unlike many who believe that we must choose between cities and suburbs, between mass transit and highways, between monolithic highrises and panoramic vistas, Safdie envisions a way to have it all. Effortless mobility throughout a region of diverse centers, residential communities, and natural open spaces is the key to restoring the rich public life that cities once provided while honoring our profound desire for privacy, flexibility, and freedom. With innovations such as transportation nodes, elevated moving sidewalks, public utility cars, and buildings designed to maximize daylight, views, and personal interaction, Safdie's proposal challenges us all to create a more satisfying and humanistic environment.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access The City After The Automobile by Moshe Safdie,Wendy Kohn in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Sciences sociales & Sociologie. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Topic

Sciences socialesSubtopic

SociologiePart I

Visions of the City

CHAPTER 1

The Ailing City

Universal Dispersal

There is a consensus today that our cities are not well. Toward the end of the twentieth century, they are inundated with problems — physical, social, and economic. Urban transportation is deficient; inner city problems have deepened; violent crime remains a serious threat in vast areas of the historic city centers.

Is there a common denominator to the ailments of cities of the industrialized West and of the populous Third World, in the North and in the Tropics — of New York and Mexico City, Jakarta and Hong Kong, Toronto and Copenhagen? Despite distinct differences of scale and resources, of climate and history, there is, indeed, a universal pattern. Everywhere in the world we find examples of expanded regional cities — cities that in recent decades have burst out of their traditional boundaries, urbanizing and suburbanizing entire regions, and housing close to a third of the world's population.1

The initial explosion of the traditional city was primarily generated by industrial-era population growth due to prosperity, better medicine, immigration, and the shrinking of traditional agricultural economies, which sent workers streaming into cities. Movement to suburbs surrounding the urban core was then facilitated by extended transit and rail lines, and finally, most decisively, by the automobile. In the United States, the most intensive growth occurred after the Second World War and was enhanced by the construction of the interstate highway system, funded by federal legislation in 1956. In 1940, cars were owned by about one person in five2; today, we are fast approaching an equal population of cars and people.

Automobiles and their road systems have completely redefined the old boundaries of cities. Today's regional city of seventy or eighty miles across encompasses the "old" downtown (or in some cases, several old downtowns), as well as industrial, commercial, and residential sprawl. As seen from the air, urbanization extends for miles beyond the old centers, clustering haphazardly along the freeway system and thickening around its cloverleaf intersections. From this distance, in fact, the car and the freeway have become the essence of the regional city.

Infrastructure Misfit

There are many conflicting views as to the impact and meaning of the exploded city in our lives. But without exception, all agree on one issue: a fundamental conflict — a misfit — exists between the scale of cities and the transportation systems that serve them. Dispersed around the region, we can no longer conform our individual paths of travel to the fixed lines of mass transit. And the more highways and expressways we build, the sooner they become overburdened with traffic; no investment in highways seems great enough to satisfy our voracious necessity to travel by car.

The automobile has devastated the physical fabric of both older and younger cities. Older cities have had to adapt their downtowns to traffic volumes unimagined at the time they were built. In these cities, which were originally served by streetcars, streets evolved with buildings lining the sidewalks, providing elaborate window shopping and ceremonious entrances for the pedestrian; together, buildings defined streets and public spaces.

Neither the scale of traditional streets, nor the size of individual building parcels, anticipated the growing volume of traffic or the need for off-street parking. Common solutions to making older cities accessible to cars have been widening streets (Montreal's Boulevard René Lévesque); displacing pedestrians to underground districts (Montreal; Toronto) or overhead walkways (Minneapolis); cutting new traffic arteries between neighboring urban districts (Seattle's waterfront; Boston's North End; downtown Hartford, CT) or through the middle of cohesive neighborhoods (everywhere); and replacing fine old urban buildings with parking lots all over the world. As the highways have taken over, the tightly woven fabric of urban streets has been progressively destroyed.

In newer North American cities, the patterns of development, land-use, and land coverage were all determined by the requirements and presumptions of car-dominated transportation from the beginning of their major growth. Each new act of city building required appropriate parking to be included at the outset, and wide urban streets were laid out and constructed with the specific goal of assuring car access. Buildings, the distances between them, and the sequences of entering and exiting them all deferred to the demands of the car. The result was an unprecedented scale and pattern: large amounts of paved open space devoted primarily to roadways and parking, with structures interspersed at distances. Every physical premise of the traditional city disappeared: continuous pedestrian circulation; a well-defined and habitable public domain; and the entire array of architectural details on buildings and streets — door frames, entry moldings, window sills, stoops, lamps, benches, trees, and all. The new form addressed the issue of vehicular access and parking, but did not replace or reinvent other aspects of urban life that had been inscribed into the older city grid over its history.

The vast majority of development in cities such as Los Angeles, Dallas, and Houston, for example, is dispersed over a region of four to six thousand square miles3 in a pattern not related to any type of pedestrian travel, but generated instead by regional highways and their principal intersections, and extended by regional arterial and county roads. With this dispersal has emerged both new building types and entirely new urban forms: the "strip," an arterial road lined with readily available parking and low-density, one-story commercial development; the mall or regional shopping center, a concentration of stores surrounded by a sea of parking and generally located on a freeway intersection; and the suburban office complex, one huge block or cluster of buildings set along a regional highway, served by a parking structure or enormous lots.

The highway has come to double as a new kind of urban street. Along these vast thoroughfares, no order of principal urban streets and public buildings exists like those that structure cities like Manhattan or Washington, DC. Highways separate office parks from shopping centers, which are separated from hotels and housing. Schools are isolated in residential suburbs, distant from cultural and recreation facilities that remain in the traditional centers. The distinguishing pattern of dispersed land uses is not a composition, but an isolation of different activities.

How have we reacted to this reign of the car? City governments have legislated requirements for ample parking in urban centers only to give up in despair, as more parking only attracts more cars, and then requires even more parking. The alternative policy, to forbid the construction of parking, aims to send commuters back to public transportation and carpooling. But while billions have been invested in subways and other urban mass transportation with some positive results (Toronto, Montreal, San Francisco, and Washington, DC), the process is often long, embattled, and immensely political. And attempts to do so in the newer automobile-era cities — Los Angeles, Dallas, Houston, Denver — often fail or are stalled because of greatly dispersed and random travel patterns, few continuous preexisting rights-of-way, and the absence of sufficiently concentrated populations.

Canada has struggled to keep its passenger train system intact, while failing to improve technology (and speed) and making no attempt to address the heavily traveled, longer-distance routes like the Montreal-Ottawa-Toronto corridor. Congestion at airports in such areas — on the roads leading to them and in the air itself — has suggested to many planners that rapid public transportation serving a region of three to four hundred miles could help alleviate the congestion associated with air travel. Yet despite the example of heavily government-subsidized rail systems built in Japan, France, and several other European countries, until very recently there has been little investment or hope of success for such rapid rail systems in North America.

But if neither more highways and cars, nor more subway lines and rapid rail as we know them today seem to fit our needs, then we either have to alter living habits that have matured over a century, or reconsider the transportation infrastructure so essential to supporting our mobile lives. In either case, we face a profound poverty of vision in planning for our cities.

The Time Is Now

Today's indiscriminate dispersal — the spatial separation of almost every type of new construction — is the product of the better part of a century's policy of laissez-faire land-use planning. In an era when market forces have been trusted to satisfy all worthwhile considerations, dispersed development has appeared not merely inevitable, but efficient and responsive to society's will. Yet our current environment clearly fails to satisfy many of our most urgent and basic needs. Never in recent history have we heard in the popular press so many calls to rebuild "community"; to create neighborhoods in which we can walk; to control car-related pollution; and to conserve our dwindling stretches of natural landscape. But any proposal to create sustained, vital urbanism today cannot be achieved for the majority of urban dwellers without an understanding of, and a confrontation with, the real, complex, and competing forces that have for decades so universally threatened our cities.

This book focuses on what these forces are, how they act destructively, and how we might take control of current patterns. Forty-three percent of the world's 5.5 billion inhabitants live in cities, many of them regional mega-cities, which are growing recklessly, increasing in congestion, and daily threatening their environment and its resources. If we are to progress, we must take lessons from the mega-city, not the Italian hill town, nor the American pre-industrial village. We must study the airport, the mega-mall, the convention centers, the enormous parking lots and structures, the freeways and their interchanges — even the sprawling strip developments along highways — for an understanding of current needs, contemporary behavior, and real economic necessities. We need not accept, but we must understand the powerful patterns that shape the city today.

Some say that mild massaging can make today's city workable. But surely the moment has come to declare "time out" — a pause, please, for reflection and assessment. Why have the old programs and investment in the prevailing patterns not worked? Why has the new expanded city failed to satisfy many of our needs for beauty, affiliation, or social commitment? How can we, as a society, begin to take responsibility not only for solving the problems we have already created, but also for planning to realize our dreams for the future?

In order to go forward and consider the city that might be, we must look at the many visions of our cities since the beginning of the massive urbanization that marks this century. What have the proposals been? Have they been tested, and if so, what have we learned from them? What were the values that guided their authors, and to what extent has society itself changed in the unfolding of the saga of twentieth-century urbanism?

CHAPTER 2

The Evolving City

Hierarchical City

Alexander the Great traveled the plains of Asia in the fourth century BC, determined to build a series of grand, new cities. As sites were selected, a generic plan was adapted to the particular features — the hills, rivers, waterfronts — of each site. Two monumental streets, the Cardo and the Decumanus, were laid out to cross each town east—west and north—south, from gate to gate. Major public buildings, theaters, palaces, gymnasia, markets, and temples were strategically placed along these principal routes. The royal administration saw to it that the main streets and public buildings along them were designed with enough formality and cohesion that altogether they formed a harmonious assemblage befitting a royal city. Individuals, on the other hand, were responsible for building the smaller-scale residential fabric of houses and workshops, extending out to the city walls.

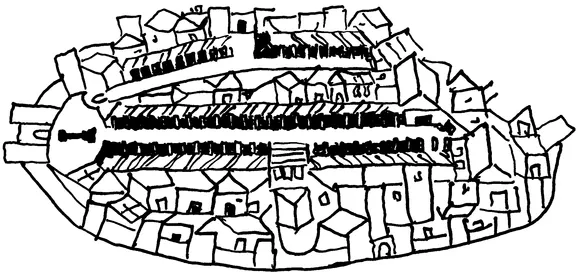

Through all Greek and Roman cities, this idea of a monumental spine forming the central lifeline of a city persisted. Byzantine Jerusalem, as described in the Madaba mosaic plan, is a vivid illustration of the principle. The walled city is punctuated by the city gates, which are the points of principal entry, and the Cardo Maximus, a sixty-five-foot-wide colonnaded street, stretches north-south, between two main gates. The Decumanus crosses at a ninety-degree angle from gate to temple in the east-west direction. The Holy Sepulcher, the palaces, the markets, and places of culture are all located along the Cardo. To this day, even with layer after layer of the city rebuilt over seventeen centuries, the same organization remains.

Madaba plan of Byzantine Jerusalem

In the centuries preceding our own, from Pope Sixtus V's sixteenth-century axial plan for Rome to the grand nineteenth-century schemes for Vienna and Paris, the public domain was the combination of principal streets or boulevards designated as important ceremonial and commercial axes, and piazzas and public buildings as focal points or formal enclosures. This model of a hierarchical city, in which the public domain and its public buildings form spines or districts through the general fabric of urban development, has produced vital places with a clear sense of orientation and legibility.

Urban historian Spiro Kostof defines pre-automobile cities as "places where a certain energized crowding of people" took place.1 Historical cities provided intense and active meeting places for commerce, the exchange of ideas, worship, and recreation. Even dictatorships produced a wide variety of spaces for formal and informal public gathering. People of diverse backgrounds came to, and lived in, the city, knowing that this conglomeration of people and the interaction offered by it would enrich their lives.

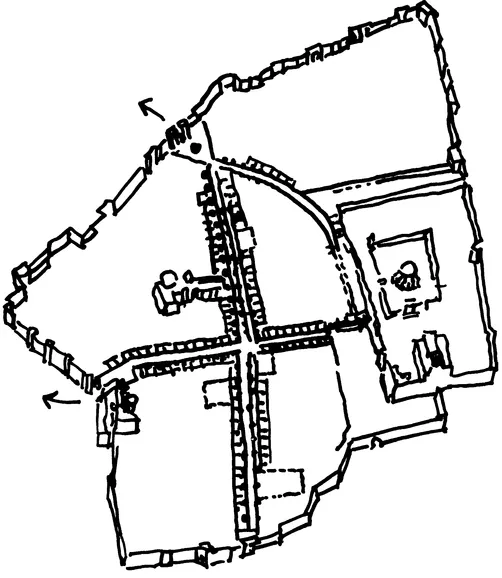

Plan of the Old City of Jerusalem today

The Modern City

At the turn of the twentieth century, during a period of unprecedented urban population growth, industrialization, and then crowding and filth — now familiar faults of industrial cities — there occurred a breakdown of many of the traditional urban systems of hierarchy and scale. At the moment, it seemed to those contemplating the future that the advent of automobiles, highways, and high-rise construction would provide an escape from the limitations and some of the oppressions of the old compact city. Greater speeds and heights held out the promise of breaking boundaries of all sorts, and, throughout the early decades of the century, inspired numerous explorations for a new kind of city.

Turn-of-the-century visionaries offered divergent recipes for the future city, and their attitudes toward density and urbanity varied enormously. Ebenezer Howard's influential "Garden City" proposal of 1898 suggested a city of dispersed low-density residential settlements. With parks at their center and agriculture at their periphery, the communities of Howard's vision appealed to those in England who still associated urban concentration with the "dark Satanic mills" (in William Blake's famous words) of the Industrial Revolution. And for the many Americans who were troubled by the influx into cities of unskilled labor from the South and new immigrants from Europe, and thus eager to distance their family lives from the hub of economic activity, the idea of living in a distant house set in nature was alluring — and, in hindsight, was a clear, early spark to the later suburban explosion.

Three decades later, Frank Lloyd Wright also resisted the idea of dense and concentrated cities. In fact, "to decentralize, he believed, was one of "several inherently just rights of man."2 His proposal for Broadacre City, a theoretical American suburban-regional city first exhibited in 1935, presented a uniform scattering of buildings across the land to satisfy this "inherent right." Small, decentralized commercial town centers — each one spatially distinct — would stand adjacent to every residential neighborhood. Like Ebenezer Howard before him, Wright assumed that these suburban cities would generate primarily local traffic, and would remain relatively autonomous and self-sufficient as communities.

Yet at the level of realistic transportation solutions, Wright's proposal broke down entirely, even at the time it was designed. In his vision, "every Broadacre citizen has his own car. Multiple-lane highways make travel safe and enjoyable. The road system and construction is such that no signals nor any lamp-posts need be seen."3 In many ways Broadacre City a...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title

- Copyright

- Contents

- Acknowledgments

- Prologue

- PART I: VISIONS OF THE CITY

- PART II: FACING REALITY

- PART III: TOWARD THE FUTURE

- Epilogue: Urbana

- End Notes

- Index