![]()

1

What Is Art?

Art is as simple as it is difficult to define. For those who belong to the “I know what I like” school, art, like beauty, is in the eye of the beholder. For others, art is any object or image that is so defined by its maker. Art can also be an object or an image not explicitly identified as such, but which strikes the observer as expressive or aesthetically pleasing.

Before there was art history and the methodologies considered in this book, there was philosophy. Philosophers have had a great deal to say about the nature of art and the aesthetic response. For Plato, visual art was mimesis—Greek for “imitation”—and techne, or “skill.” And beauty was an essential ideal that expressed the truth of things. But beauty and truth, in Plato’s view, were of a higher order than art. In fact, he had little interest in works of art because they were neither useful imitations of essential ideas nor the ideas themselves.

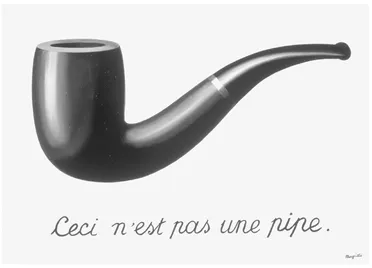

Take the example of Magritte’s twentieth-century The Betrayal of Images, which is a convincing painting of a pipe [1]. According to Plato, there would be, in the world of ideas, an essence of perfect “pipeness.” A pipe in the real world, on the other hand, might be useful, but it would lack the perfection of the ideal pipe. The painted image of the pipe, however, is neither useful nor ideal—as is implied by Magritte’s written text. For Plato, therefore, the image is the least “true” of the three conditions. Magritte’s title—The Betrayal—indicates that he, like Plato, believed that pictorial illusion is treacherous. But whether, as an artist himself, Magritte would agree with Plato’s banishment of artists from his Republic, or ideal state, is another question.

1. René Magritte, The Betrayal of Images, 1929, Los Angeles County Museum of Art.

In contrast to Plato and the Platonic tradition of ideal essences that artists strive to imitate, Aristotle’s empiricism allowed for more possibilities. Even though he followed Plato in the basic conception of art as a combination of mimesis and techne, he did not restrict it to the exact, or “essential,” copy. To know a thing, in Aristotle’s view, one had to know its matter, its maker, and its purpose, as well as its form. He thought that art could improve on nature by various means, such as idealization and caricature. These achieve an “essence” of a different kind and accord the work of art some grounding in the artist’s perception.

Plato banished the artists because he considered their images to be deviations from the truth (and therefore from the Good and the Beautiful—the kalos k’agathos). He also objected to art—to music and poetry—as capable of inciting destructive passions. Aristotle, on the other hand, believed in the power of art to repair the deficits of nature. These ancient Greek philosophical positions address the origins of art as well as its character. For Plato, art derives from an ideal, but its distance from that ideal makes it useless at best and possibly dangerous. For Aristotle, art can be a route to knowledge. He believed that we are delighted by a good imitation because we can learn from it, and that this makes us delight in learning itself. Whereas for Plato the original ideas—and not the art—contain truth and beauty, for Aristotle truth and beauty are contained in the forms and structures of art.

These and other philosophical issues have addressed the question, What is ART? right up to the present day. In 1927 this question had its day in court. At issue was a sleek bronze sculpture entitled Bird in Space by the Romanian artist Constantin Brancusi [2] (and see cover image). The American photographer Edward Steichen had purchased the Bird in France, and on his return to the United States he declared it to customs as an original work of art. In American law, original works are exempt from import duty, but the customs officer rejected Steichen’s claim. The Bird, he said, was not ART, and it entered the country under the category of Kitchen Utensils and Hospital Supplies. Steichen had to pay six hundred dollars in tax.

Later, financed by Gertrude Vanderbilt Whitney, the American sculptress and founder of the Whitney Museum, Steichen sued. Testimony revolved around the nature of art. Conservatives championed the Platonic view of art as mimesis and techne, and wanted to know why the Bird had no head, feet, or tail feathers. To the conservatives, the Bird was neither an accurate imitation of nature nor the product of a skilled technician. According to the modernists, on the other hand, the Bird satisfied the essential criteria of “birdness.” For them, Brancusi had captured the very essence of a bird suspended in space. Its graceful form expressed qualities of birdness as perceived by the artist, and its high degree of polish evoked its relation to the sun when in flight. Furthermore, the modernists testified that Brancusi had called his sculpture a bird, which was sufficient evidence that it was indeed a bird. Their position thus approximated Aristotle’s view of art as originating in the perceptions of the artist. On this occasion the modernists prevailed, and the court ruled in Steichen’s favor. Brancusi’s Bird was declared a work of ART.

2. Constantin Brancusi, Bird in Space, 1941, Musée National d’Art Moderne, Centre Geroges Pompidou, Paris, France.

Aesthetic value judgments of the kind illustrated in Steichen’s court case and disputed by the philosophers are not the central issue of art history. The latter has traditionally focused on identifying, cataloguing, and characterizing specific works or groups of works. Nevertheless, the art historian has to make certain judgments in selecting the work to be considered.

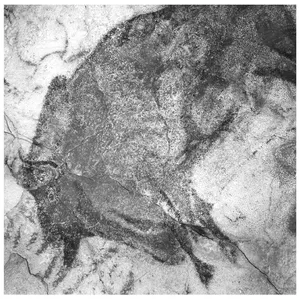

Art history deals with ancient as well as contemporary works, which raises new questions about the nature and definition of art. For example, when we see a painting over ten thousand years old on a cave wall—say at Lascaux in the Dordogne region of France, or at Altamira in Spain [3]—we know that the painter did not call it “art” in our sense. Our concept of “art” began to take shape during the eighteenth century. If a cave painting depicts an animal, as most do, we suspect that it functioned as a kind of picture magic and symbolically “captured” the animal necessary for the survival of the Paleolithic (Old Stone Age) hunting society that created the image. Today, people who make paintings are called artists. But we view cave paintings over a span of time and are far removed from the original context. When we “suppose” picture magic, we are trying to reconstruct the context based on what we know, or think we know, of the Old Stone Age, and our reconstruction is influenced by the theory that images of that period were part of wider religious and magical belief systems.

3. Room of the Bisons, c. 15,000–10,000 B.C., Altamira Caves, Spain.

Our assessment of the artist depends partly on our perception of what the notion of “art” represented to a particular society at a particular time. Since the identities of artists from certain societies and time periods are unknown, one function of art history is to determine attribution—that is, to match the names of artists with the works of art from a specific time and place. Whether or not attribution is possible depends on the vicissitudes of historical preservation, or lack of it, on the nature of the culture in question, and on the skill of the person making the attribution. In certain periods of Western art, notably ancient Greece and Europe from the Renaissance to the present, artists’ identities are better known and more easily connected with works of art than, for example, in the Middle Ages. From the nineteenth century, various methodological approaches to works of art have developed, and these provide us with different ways of thinking about images, artists, and even critics. In the best of all possible worlds, these “methods” of artistic analysis do not compete but rather reinforce one another and reveal the multifaceted character of the visual arts.

The Artistic Impulse

One thing that can be confidently said about “art” is that it derives ultimately from an inborn human impulse to create. Give children crayons, and they draw. Give them blocks, and they build. With clay, they model; with a knife and a piece of wood, they carve. In the absence of such materials, children naturally find other outlets for their artistic energy. Sand castles, snowmen, mud pies, scribbles, and tree houses are all products of the child’s impulse to impose created form on the world of nature. What children create may vary according to their environment and experience, but they invariably create something. This is borne out by biographies and autobiographies of artists, which frequently record a drive to draw, paint, sculpt, or build in early childhood. How such childhood drives are channeled depends on a complex interaction between the nature of the society, the family, and the propensities and experience of the individual.

All the creative arts—including the visual arts—separate the human from the nonhuman. Animals build only in nature, and their buildings are determined by nature. These include birds’ nests, beehives, anthills, and beaver dams. Mollusks, from the lowliest snail to the complex chambered nautilus, build their houses around their own bodies and carry them wherever they go. Spiders weave webs, and caterpillars spin cocoons. But such constructions are genetically programmed by the species that make them, and they do not express individual or cultural ideas.

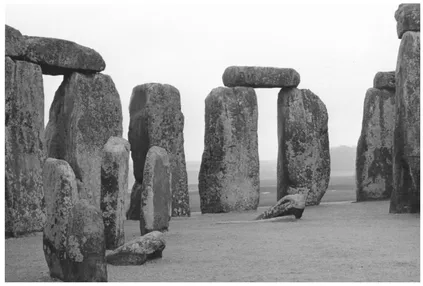

People, on the other hand, build in contrast to nature, even though buildings can be related to nature. The Neolithic cromlech, or circle of stones, at Stonehenge, for example, is both distinct from and related to its natural environment [4]. About 3000 B.C., Neolithic builders chose as their site the broad, flat plain now called Salisbury in the county of Wiltshire in England. Over the next twelve hundred years, Stonehenge developed into the last monumental cromlech of the Neolithic period in Western Europe. By around 1800 B.C., its builders had arranged the monolithic stones into a significant form and placed horizontal lintels on top of vertical posts.

4. Stonehenge, c. 1800 B.C., Salisbury Plain, Wiltshire, U.K.

Because of its open spaces and unpolished surfaces, Stonehenge strikes viewers as naturally related to the site. It also creates a visual transition between earth and sky. But it is distinct from nature in being man-made and in expressing cultural ideas. It reflects, for example, the belief that stones are imbued with a magic power to fertilize the earth. And on a broader level Stonehenge exemplifies the monumental stone architecture that developed when people made the transition from Paleolithic hunting societies to agriculture.

The Gothic cathedral at Chartres, begun in A.D. 1194, differs from Stonehenge in the degree to which it relates to nature [5]. Whereas Stonehenge is constructed on a flat, green expanse of land, Chartres rises from the highest point of a medieval French town. The cathedral builders used height to express the Christian belief that heaven is located in the sky and the aspiration to achieve it after death. Instead of a flat plain, the Gothic builders chose a naturally elevated site to enhance the soaring movement of the vertical spires. But the cathedral’s formal relationship to nature ends there. As a work of architecture, Chartres is more differentiated than Stonehenge; its interior has been enclosed by stone walls, stained-glass windows, and a roof. Its exterior is decorated with hundreds of sculptures and carved architectural details.

Animals come by their “architectural” skills naturally, but in most human societies one needs some training and formal study to become an artist. Even the so-called naive, or self-taught, artists study art and master certain techniques. The formal and technical control achieved by human artists is learned over time and with practice. Although the artistic impulse is inborn, someone had to teach Paleolithic children to paint cave walls, and medieval children had to learn various crafts, including engineering, in order to ensure the realization of Gothic cathedrals. Renaissance children studied for years as masters’ apprentices before becoming masters themselves. But there are no art schools or apprenticeships in the animal k...