- 224 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Teaching Problem Solving in Vocational Education

About this book

The development of thinking skills which will improve learning and problem-solving performance at work is an important aim for vocational education and training. The best of workers - manual, technical, administrative, professional, scientific or managerial - have gained skills in problem solving. This book provides guidelines on how best to teach those problem-solving skills. Rebecca Soden argues that thinking skills are most effectively developed along with vocational competences, and offers practical strategies on which training sessions can be based.

Trusted by 375,005 students

Access to over 1 million titles for a fair monthly price.

Study more efficiently using our study tools.

Information

Topic

EducationSubtopic

Education GeneralChapter 1

Thinking matters at work

There was a time when the dividing lines were clear between jobs which needed thinking workers and ones which were so routinised that thinking was an unnecessary and even unhelpful skill. All of you who are involved in planning and delivering vocational education and training programmes know that more people than ever before are expected to be able to adjust their performance to accommodate everyday variations in task demands. Faced with a non-standard task or situation, they should be able to respond effectively. This helps define an important aim for vocational education and training in both the school and post-school sector. This aim is the development of thinking skills which are necessary and sufficient for flexible and adaptable performance of work tasks. Such skills also enhance learning, thereby offering the potential to improve levels of achievement. The notion of ‘vocational A levels’ implies a vocational curriculum which develops complex thinking skills.

This book will focus on those thinking operations which are most useful in skilled jobs in areas as diverse as catering, caring, engineering and business studies. These jobs and many others mentioned in the following chapters employ many thousands of people. To get their work done all of these people must work to agreed national standards and develop vocational competences. The best of workers, whether they be manual, technical, administrative, professional, scientific or managerial people, have gained skills in problem solving. This book provides guidelines for teaching those problem-solving skills.

Derived from cognitive theories about learning and problem solving, and from five research projects recently funded by the Employment Department, these guidelines will assist further education lecturers, teachers caught up in the increasing trend to vocationalise secondary education, and managers who have some role in facilitating the development of people.

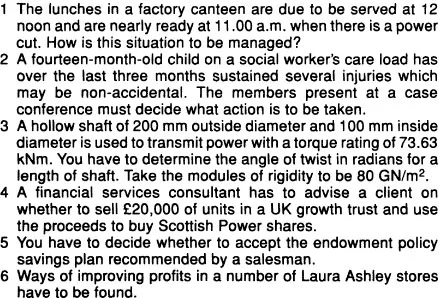

In every occupational area thousands of people, of all ages and various experiences, are now seeking National Vocational Qualifications (NVQs). Increasingly, thinking skills are being emphasised. A traditional view of reasoning is of mental processes that can be tapped independently of the situation which is being reasoned about. An alternative recent view is that there are no such things as thinking processes detached from the context in which they are being applied. Rather, the information which people use in reasoning about situations and the form of the reasoning are inseparable. The practical significance of this alternative view (on which this book is based) is that thinking skills are most effectively developed along with vocational competences and not as the separate ‘add-on’ courses which have been popular in schools and colleges. The problems in Figure 1.1 from different occupational areas illustrate the diversity of contexts in which thinking skills are applied.

Figure 1.1 Problems in different areas

The last problem was drawn from an experiment carried out during 1992 when staff in a number of Laura Ashley stores were given a free hand in solving the problem, with cash incentives linked to profits. Results were so much better than anticipated that the scheme is being developed. Reasoning by branch staff about increasing their own branch profits may be particularly effective because no one has had more practice than these employees in reasoning with the strands of information peculiar to that branch.

Effective financial consultants dealing with problem (4) above would reason with the technical information which is accumulated by competent practitioners. Out of this information would arise questions which are particularly effective for solving problems in this domain. They might, for example, ask about social, political and economic factors which currently, or in the near future, will influence both the costs of producing electricity and the price which can be obtained for the electricity. They would also ask questions about price/earnings ratios and dividend cover for the investments being considered. In tackling problem (5), questions need to be asked such as:

‘What charges will be made for managing my money?’

‘How much commission will you earn by selling me a policy?’

‘Can I lose money under any circumstances?’

‘Why should I give you my money rather than the building society?’

The canteen power cut described in problem (1) is discussed in Chapter 8, pages 142–3 and you will find a solution to problem (3) in Chapter 9.

These problems illustrate that thinking is closely bound up with what is being thought about. Central to thinking is interrogation of our own knowledge (in memory), a process which can both release information needed to solve problems and enable missing knowledge to be created. This relationship between thinking and information on which the thinking is based helps to explain the finding that people who are avid race-goers can solve complex problems when they are reasoning with race-track information but often cannot apply similar reasoning operations to problems outside the context of the race-track. This is not to say that people cannot learn to apply reasoning operations which they have learned in one situation to another, but that transfer is more problematic than is often implied in popular accounts of problem solving.

The distinctiveness of the approach lies in its synthesis of various findings in cognitive psychology to produce guidelines on teaching occupational problem-solving skills. These skills are gained in the course of imparting vocational knowledge rather than being taught in a separate, generic problem-solving course. What distinguishes this approach is its central idea (derived from Vygotsky’s work) that any instructional activity can, and should, have a dual focus. First, it must of course contribute to achievement of the targeted competence. It is the second focus which is mostly neglected. This is the teaching of thinking skills which are inextricably linked with competences.

This book describes how you can adapt your existing strategies to achieve this extra yield. In this approach you analyse the mental processes which underlie learning and problem solving in your own occupational area. Drawing on the principles and illustrations in this book you can introduce these processes with the vocational content at each training session, and ensure that all practice includes practice in using these thinking skills. Integrated into the book are the well-researched messages which emerged from five recent Employment Department funded projects, one of which was carried out by the book’s author. The approach is sufficiently student-centred to satisfy the most progressive educator, systematic enough to win the enthusiasm of the most traditional, while its potential for reducing training costs attracts the support of employers.

Crucial to your success is understanding that the central feature of the approach is development of the learners’ insight into the nature of thinking and not merely formation of efficient thinking procedures for particular types of problems. If the approach seems ‘teacher-centred’ in places, this is because the mental processes required for learning and problem solving have to be taught systematically and not left to chance. A moment’s thought will convince you that being able to ask appropriate questions is an important element in professional competency and that this aspect of competency has to be practised. For example, unless you have been exposed to systematic instruction in chemistry it is unlikely that you can ask questions which will lead to the solution of problems. Yet learning to learn and think is left to chance.

Post-school vocational education and training are vocational in the sense that they are specifically concerned with preparation for or improving performance in particular occupational areas. Vocational competences are accredited by the award of National Vocational Qualifications (NVQs) and their Scottish equivalents (SVQs) at different levels. Traditionally, vocational education and training programmes leading to lower-level qualifications, the precursors of the present NVQ levels 1 and 2, were intended to equip people to carry out routine occupational tasks quickly and accurately, whereas higher-level programmes (degrees, HNCs) were intended to equip people to deal with tasks of a more complex and varied nature which would require good thinking skills. Changes in the nature of work have led to increasing recognition that most workers need to be thinking workers. ‘All education and training provision should be structured and designed to develop self-reliance, flexibility and broad competence as well as specific skills’ (CBI 1990). Wolf and Silver (1993) state that ‘broad skills …. are the thinking and problem solving skills underlying competences … together with critical job specific knowledge’.

The introduction of General NVQs reflects a significant move towards more broad-based training and the promotion of transferable skills. As noted on page 6 problem solving, which is a behavioural manifestation of efficient thinking, is one of the ‘core skills’ in the NVQ Framework for Core Skills. The approach in this book is relevant also to the development of the other core skills – communication, numeracy, information technology and interpersonal effectiveness – which are also manifestations of thinking. Despite the obvious point that thinking processes underlie these competences, much instructional effort focuses on performance of tasks with little regard for developing the intellectual processes underlying performance. Blagg et al. (1993) comment, ‘In spite of good intentions even more able trainees with NVQs at levels 1 and 2 remain inflexible and unresourceful when faced with the unfamiliar.’

Given this neglect of thinking skills, it is perhaps not surprising that there is good evidence from various sources that people are not very good problem solvers in practical situations. Edward de Bono reports: ‘the many hours of tape recording that we have listened to at the Cognitive Research Trust suggest that the standard of thinking of many pupils is appallingly low. In the more able pupils this is obscured by an articulate style.’ He concludes that ‘most schools do not teach thinking at all’. Similar evidence comes from research in the post-school setting. In ‘Six years on’, the Scottish Office Education Department report on National Certificate programmes, it is noted that ‘while examples were found of programmes with a strong emphasis on problem solving’, this was not characteristic of the system.

That many workers do not think efficiently can easily be confirmed by reference to your own everyday experience. In the service industries, an unthinking approach often alienates customers. In other sectors of industry, expensive and dangerous errors can often be avoided by employees who can deal with tasks which take a non-routine turn. De Bono points out that:

it is very easy to have a general intention to teach thinking as a skill. It is very easy to assume that one has always done this anyway. But when you actually set out to teach thinking directly as a skill it is difficult unless there is something definite to do.

This emphasises the importance of ensuring that the ‘something to do’ is derived from an accurate notion of what is involved in thinking. As practitioners in vocational education and training, you will find in this book a sound approach to understanding thinking and workable suggestions for translating this understanding into practice in your own occupational area.

While much of the demand for thinking workers has come from employers, learners’ interests are also better served by programmes which help them to become thinkers as well as doers. An important claim for academic education is that it develops intellectual abilities of a broad, transferable nature. The evidence that only a few can achieve such skills is fast crumbling, and if there is to be genuine parity between academic and vocational education the teaching of thinking skills must be taken seriously.

OUTLINE OF THE BOOK

Although the book focuses on teaching thinking skills, it is also designed to serve as a basic applied psychology of learning text for vocational teachers and trainers who are seeking teacher/trainer accreditation. Competency-based vocational education implies problem solving in the sense that the objective for the learner is application of knowledge in a range of working situations. This book differs from most ‘psychology for teachers’ texts in that it starts from a ‘core skill’ – problem solving – the learning of information being combined with learning to apply it in occupational life. This core skill must be acquired to qualify for GNVQ/GSVQ awards. What is not attempted is the usual ‘compare and contrast’ tour round cognitive theories but rather an attempt to show how elements of these theories can produce instructional guidelines for vocational tutors. In other words, the focus is on the practical use of cognitive psychology rather than looking at the supporting evidence which can be found in a general psychology text.

Since theories about motivation are explored in most psychology texts and in many books about management, there are no chapters in this book which focus specifically on motivation. There is no universally accepted theory of motivation within psychology. Underlying the ideas in this book is a commitment to research-based cognitive approaches to motivation. Such approaches view people as making choices which are rational in the light of the alternatives they perceive to be available to them. People weigh up the attractiveness of outcomes, the probability of successfully achieving different outcomes and the costs in terms of efforts. The effect on the person’s self-esteem from following a particular course of action is an important consideration in appraising alternatives. People will perceive some experiences as potentially damaging to their self-esteem and others as offering a reasonable chance of enhancement. Whether the experiences are likely to be boring or interesting will also be taken into account in making choices, even when the alternatives are limited.

Problem-solving skills are useful in a wide range of social and work activities, and are socially desirable skills which enhance status in many social groups, including those who do not usually conform to mainstream society’s norms. Cognitive approaches to motivation would predict that these features of problem-solving skills would help to harness people’s efforts towards their development. There are also features of the methods currently being advocated for developing thinking skills which make for more interesting instructional sessions and which reduce the fear of failure which discourages people’s efforts to extend their abilities. The creation of a co-operative, non-judgemental learning environment where ideas are explored and developed rather than being pronounced right or wrong is central to teaching thinking skills. Interest is more likely when the instructional focus extends beyond routine tasks. This must happen in learning problem-solving skills which require practice in thinking about, implementing and evaluating solutions to problems. There is sound evidence that people are more interested when a task is just beyond what they can at present understand and do, but not so far in advance of their present capacity that it is not worth trying to crack the problem. A curriculum which is built around problem-solving skills has many features which harness motivation. It provides a richer learning environment in which motivation is not such a big issue as in some traditional programmes.

In Chapter 2 a definition of problem solving and a brief description of its basic intellectual components are introduced and explored through examples of...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Dedication

- Contents

- List of activities

- List of figures

- Preface

- 1 Thinking matters at work

- 2 Learning to solve problems and learning as problem solving

- 3 Information matters in learning and problem solving

- 4 Learning to learn for problem solving

- 5 Teaching mental procedures for problem solving

- 6 Writing instructional plans – conventional and dual focus

- 7 Transfer and assessment: rocky roads to travel

- 8 Problem solving in kitchens

- 9 Problem solving in sequential logic, transposition of formulae, applied chemistry and cardio-pulmonary resuscitation

- 10 A problem-solving approach in basic principles of accounting

- Appendix: A background to theory and research

- Index

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Teaching Problem Solving in Vocational Education by Rebecca Soden in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Education & Education General. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.