- 309 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

This is an attempt to catalogue the reasons why some wars are so difficult to stop - even when both sides want the fighting to end. Through detailed case studies, the book assesses the obstacles and points toward solutions for ending wars more quickly. Each chapter is devoted to a specific obstacle which the author analyzes and then illustrates with case studies, drawing on such conflicts as the Iran-Iraq War, the Gulf War and the Yugoslav wars. He assesses the role of third parties in trying to persuade people to stop fighting and examines what happens when obstacles to a cease-fire cannot be overcome.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Stopping Wars by James D D Smith in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Politics & International Relations & Politics. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Part One

Introduction

1

The Long and Winding Road to Peace

The road from war to peace is a puzzling and uncertain one. To those who fight and die on it, it is seldom clear just when the journey will end; those responsible for finding the path are rarely more perceptive. Of the few signposts that exist, perhaps the most visible is the cease-fire:1 no war ends without one. To reach that point on the road, however, a number of obstacles must be overcome. Many of these will be conflict-specific; that is, they are more or less unique to the violent conflict in question, and are either unlikely to be encountered a second time, or are too specific to place into broad theoretical constructs. It seems likely that at least some of the difficulties encountered, however, will be common to virtually all cease-fire negotiations, whether between or among non-state or extra-state actors, nations and nation-states. These difficulties, strewn like rubble across the path to peace, come up time and time again, and if attempts at stopping wars are to be consistently successful, they need to be identified and addressed. This book, then, is an attempt to understand what stops wars from ending. More specifically, since there must be a cease-fire before any war can end, and since the cease-fire is the most obvious sign that the war may be ending, the book is an attempt to catalogue the most common barriers to successful cease-fires in international and civil wars.

At first glance, there is a single, uncomplicated explanation to this problem, one that many of us have been hearing all our lives. As a child, I can remember watching footage of the Second World War and other conflicts, and thinking, "Why can't they just stop fighting?" I could not accept the possibility that all those people really hated each other so much and that there was no more sensible way to resolve their differences. When I asked adults the answer to my question, they invariably replied, "Because they don't want to stop." (In academic terms, the political will was absent: the leadership, whoever they may have been, believed that more could be gained by fighting than by not fighting.) Today, the violence of the former Yugoslavia, of Somalia, and of Rwanda and elswhere, leads me to ask the same question I did when I was younger, and people still give me the same reply now as they did then. One of the points of writing this book is to propose that their answer, sincere and guileless though it may be, is simply not good enough.

Admittedly, the most obvious obstacle to stopping a war is in fact a lack of political will. Unless it is present, and excepting those cases where a cease-fire is imposed, no cease-fire will occur. Yet even where there is some will to cease fire, what researchers have failed to recognize is that a number of factors sometimes affect its translation into effective and sufficient political will which actually brings the fighting to an end. This study therefore qualifies and deepens the more traditional theories of war termination which suggest that where both sides want an end to their war, the war will end.2

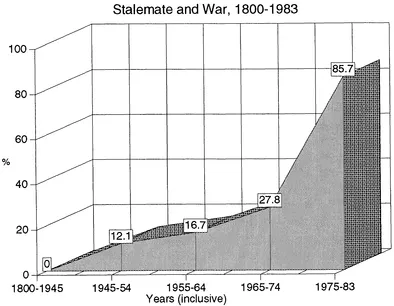

FIGURE 1.1: Stalemate and War, 1800-1983. Percentages refer to wars where military stalemate was considered to be the decisive factor in belligerents' decisions to try to end the war. Raw data can be found in Dunnigan and Martel, 1987, pp. 207-262. It is noteworthy that their own (valid) conclusion was that only 11% of wars since 1800 have ended in stalemate (p. 270).

Thus, by the end of this book it should be clear that there are identifiable obstacles to cease-fire which are common enough that they may exist in every international and civil war. As with any obstacle blocking a path, they may come in different combinations and be more or less difficult to surmount — but they will arise. Moreover, and more worrying, these obstacles interact; the existence of one obstacle often increases the likelihood that other obstacles will arise. These latter barriers may then affect and strengthen the original one, and the cycle may continue. (See Appendix 2 for an illustration.) The existence of any obstacle decreases the likelihood of a cease-fire, and while their removal does not automatically end the fighting, it will make this more likely.

For anyone with a humanitarian interest in ending war, the importance of understanding the process of cease-fire should be obvious: if we can work out how to remove these barriers, actively encouraging possibilities for cease-fire, the chances of being able to stop the violence must increase dramatically. On the practical level, too, an understanding of the process is a sensible step. It is of course possible to argue that when there is a straightforward winner/loser relationship between belligerents3 at war's end, making cease-fires successful is both less of a problem and less interesting; although terms for cease-fire must still be accepted, the victor can often dictate those terms with relative impunity — "Do what I say, or else. " However, where the "winner" is less clear, or where no winner is present — such as in the case of a stalemated war4 — stopping the fighting tends to be much more laborious and intricate. The power relationship between belligerents is more equal, but the belligerents themselves may not see it that way, and may make conflicting demands justified on the basis of how much power they think they have. It is thus that an understanding of the process of cease-fires is important in a practical sense, for whereas wars in the past have tended to end on clear victor-vanquished terms, this appears now to be much less often the case.

In the past, many studies have looked at war statistically in order to discover trends of one sort or another." Two more recent works — Paul Pillar's Negotiating Peace (1983) and Dunnigan and Martel's How to Stop a War (1987) - indicate (inadvertantly) that there is a strong trend in modern times towards war ending in something other than clear winner/loser belligerent relationships. Pillar's data, for example, tells us that most modem wars (64%) end either through negotiation, or with the withdrawal of all parties to the conflict.6 Dunnigan and Martel's data included 389 wars of varying types from 1800 to 1987/ Assuming the data is reliable, and specifically from the point of view of the relevance of stalemate, the picture is even more remarkable. Figure 1.1, compiled here and based on their raw data, provides a dramatic visual illustration of the growing importance of stalemate as a factor in ending war.

"Victory," then, is becoming increasingly elusive in modern warfare. The quick and decisive victories of both the Falklands War and the Gulf War of 1991 are exceptions to a rule — the numbing stalemate of the Iran-Iraq war is more representative. It is precisely because a negotiated settlement on relatively equal terms will be the eventual result in most cases that it may be no more than an act of pragmatism to understand the best way of initiating the move toward settlement. In other words, because it will make sense to seek (as a minimum) a cease-fire at some point, it makes all that much more sense to understand from the start exactly what may act as a barrier to that objective.

The realization that all wars must end at some point, that a cease-fire is a necessary part of that process, and that it might be a good idea to understand as much about that process as possible, seems to be lost on political leaders generally and on war theorists in particular. In 1970, William T.R. Fox noted that "[w]hat makes wars end ... and what keeps wars from ending, has been much less studied than what makes wars start... or what keeps them from starting."8 One explanation for this, of course, is that if war can be prevented, there is no need to study how to stop it9 (thus the concentration on the causes and prevention of war10). It may also be felt that to study how a war ends may be tantamount to conceding that it cannot be prevented -- something many (this author among them) would be loath to admit.

Whatever the explanation, Fox's observation still holds true. Even today, there are still very few major works on war termination." As for cease-fires, they seem to be of even less concern. Where it is mentioned at all, the ceasefire is considered only as a mere stage in the larger process of war termination — and not necessarily its most integral stage.12 The obvious value of what does exist is granted, but even the most recent works did not have the opportunity to consider some of the more interesting conflicts from the point of view of war termination and cease-fires: the Iran-Iraq war (one of the most devastating conflicts of the twentieth century), the Gulf War (a war conducted in the "new" international environment), and the Yugoslav conflict (a failed attempt at an imposed cease-fire), to name just three.

The point, in the end, is this: while research into war termination and cease-fires may be on the rise, and while that research may be relevant, as far as cease-fires go, a great many questions have to this point been left unanswered or inadequately answered. What exactly is a cease-fire, and how does it differ from related terms such as truce or armistice? What obstacles exist in trying to effect a cease-fire (humanitarian or otherwise)? What problems exist in negotiating a cease-fire agreement? What problems exist in actually implementing agreements once they have been negotiated? Are there common obstacles and problems? Are there common solutions? This book is by no means an attempt to answer all of these questions, but it will attempt to answer at least some of them.

This does not mean that specific solutions will be provided to all the problems raised. Solutions are of obvious importance, but no solution will be forthcoming before a complete understanding of the problem; this book is about understanding the problems. Having said that, by the end of the book some general ideas about dealing with these difficulties will become clear, and some ideas will be put forward as the problems are discussed. The book closes with some recommendations, but these are certainly not intended to be the final answers. They are merely to be used as points of discussion, or as jumping off points to find the best answers. So, in sum, this is not a "how-to" book on stopping wars; it asks a different question: "What makes stopping wars so hard?"

In order to answer that question, we will look at relevant war termination literature, as well go through a number of case studies. The latter consisted of selected international and intrastate wars13 which have occurred since 1945,14 the year when, with the end of the Second World War and the creation of the United Nations, the modern international environment came into being. Wars chosen for analysis within that period were selected for a variety of reasons. Some were chosen for the reason that the war was perceived by belligerents as being a "fight to the death"; the Algerian War of Independence is a good example. Others were chosen primarily because of the significant number of casualties which resulted, such as the Nigerian Civil War (over 2 million dead). Finally, the war may have been a primarily stalemated war, or had an international component which highlighted the degree to which the global community held it to be important (the Iran-Iraq war, for example).15

Some of the criteria may seem callous, but the intention was to take those cases where it was assumed that the obstacles to cease-fire would be strongest, where both sides would be the most committed, and where the efforts of third parties to end the conflict would be at their most intense (yet generally ineffective). They are in that sense "worst-case" studies, and were chosen on that basis. If the obstacles to cease-fire can be understood in these cases, it may be easier to understand what it takes to surmount such obstacles in future, less "serious" cases (or to understand that they cannot be surmounted).

It is important to understand that this book does not assume cease-fires are always a good idea. It is readily admitted that cease-fires do not automatically resolve any of the underlying political issues in any given conflict. Furthermore, cease-fires "may simply fix the conditions under which the fighting will be resumed, at a later date, and with a new intensity,"16 an assertion which highlights the importance of resolving the underlying conflicts. Sydney Bailey has pointed out that if "one party is more responsible than the other for the outbreak of hostilities, an immediate cease-fire may place it in an unduly advantageous position."17 Pillar has argued that peace negotiations in general can be used "an extension of combat, a nonviolent way of bringing about some of the results of combat."18 In all these cases, the humanitarian intentions often implicit in cease-fire effectuation would appear to be inadequately served, and all these difficulties need to be addressed.19

The cease-fire is, however, a means to an end: whether or not it was the original intention of the belligerents or concerned third parties, the cease-fire will (by definition) create an atmosphere relatively — if not completely — free of violence, an atmosphere in which, given time, a more permanent peace can be concluded. As one cease-fire mediator has put it, "if people stop shooting at each other for one day, they have broken the habit. Perhaps they might find that it feels pretty good."20 Moreover, it should be obvious that a cease-fire is a necessary condition of both ending the war, and of resolving the conflict. Finally, a successful cease-fire always has a humanitarian component; the saving of lives is an inevitable and undeniable advantage to any cease-fire. The crucial point, however, is this: while a cease-fire may be impractical or undesirable at certain points within the time span of a given conflict, it is always desirable at some point in the conflict, and we therefore need to understand what may stand in its way.

Given all of this, it remains only to briefly outline the contents of the chapters to follow, if for no other reason than to impart a sense of the direction of the study. Here, at least, we can provide a relatively clear path.

The journey begins with an examination of the most obvious necessary condition for cease-fire: a willingness to consider ...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title

- Copyright

- Dedication

- Contents

- List of Figures

- Acknowledgments

- PART ONE INTRODUCTION

- PART TWO BELLIGERENTS DURING WAR

- PART THREE THIRD PARTIES AND WAR

- PART FOUR CONCLUSIONS

- Appendix 1: Notes on the Definition of "Cease-fire"

- Appendix 2: "Why can't they just stop fighting?"

- Appendix 3: Case Study Chronologies

- Bibliography

- Index

- About the Book and Author