- 352 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

Illustrated with Barbara Hepworth's abstract stone carving, with other works of art, and with fascinating vignettes from Adrian Stokes's writing, this biography highlights his revolutionary emphasis on the materials-led inspiration of architecture, sculpture, painting, and the avant-garde creations of the Ballets Russes. In also detailing Stokes's role as catalyst of the transformation of St Ives in Cornwall into an internationally-acclaimed centre of modern art, and his falling in love again in his early forties, this biography shows how Stokes used all these experiences, together with his many years of psychoanalytic treatment by Melanie Klein, in forging insights about ways the outer world gives form to the inner world of fantasy and imagination.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Art, Psychoanalysis, and Adrian Stokes by Janet Sayers in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Psicología & Historia y teoría en psicología. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Part I

Childhood and Youth

Chapter One

Early years

“Going down the hill one morning towards Lancaster Gate, my eldest brother remarked on an orange cloud in a dark sky: a thundercloud, he said. And sure enough, that afternoon there was a thunderstorm,” recalled Adrian Stokes at the time of doodlebug raids on England in the Second World War. “At nearby Stanhope Gate, an old lady sold coloured balloons. It was as if the whole lot had burst,” he continued in recalling himself aged six and his eldest brother, Philip, before the First World War.1

Philip, it seems, had been named after his and Adrian’s stockbroker grandfather, Philip Leon, who had died when his daughter, Philip’s and Adrian’s mother, Ethel, was six. Through her mother she was related to the once famous financier, banker, philanthropist, and Sheriff of London, Sir Moses Montefiore.

Adrian was “pleased about the Montefiore” connection “but not about being Jewish”.2 Perhaps he was more pleased that his father, Durham, came from a non-Jewish Irish family. Born just over a year before Ethel on 8 April 1871, Durham also lost his father early, not through his father dying but through his father deserting Durham, his older sister, and their mother. It was this, apparently, which caused Durham to leave school, St Paul’s in Hammersmith, where he had proved an able mathematician, at the age of sixteen, and obtain paid work in a solicitor’s office where, he bragged, he received a pay rise through getting a firm across the road to offer him a higher salary.

By the time he married Ethel on 15 August 1896 Durham was working (like his father, Edwin) as a stockbroker in the City. His and Ethel’s first child, Philip, was born on 15 August 1897. The same year Durham was sufficiently wealthy to buy a grand terrace house, 18 Radnor Place, which, with its classical brick and stucco façade, was similar to handsome-looking houses in nearby Sussex Gardens.3

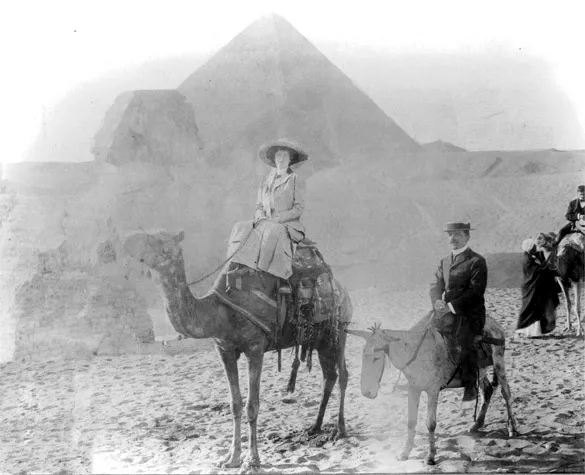

Ethel Stokes, 1898

It was at 18 Radnor Place that Adrian’s brother, Geoffrey, was born on 19 April 1900, and that Adrian himself was born on 27 October 1902. Ethel was disappointed that he was yet another boy. She had wanted a daughter. She was nevertheless very fond of Adrian and even more fond, it seems, of herself; she had been a great beauty in her youth, and was remembered by Adrian as vain, “frigid”, and obsessed with “order and cleanliness”.4

He also recalled her dislike of Durham. Not without reason. Durham was evidently a tyrant at home. This included his saving money, despite being a remarkably successful stockbroker, by starving Ethel of adequate heat and light, and by forbidding her to make outgoing telephone calls. He was also ridiculously penny-pinching with himself. Examples included his only allowing himself “a three penny cigar after breakfast, a six penny one after luncheon, and a shilling one after dinner”. And he dominated the family with his absurd ruling that dinner must be at “8.14” and lunch at “1.11”.5

Ethel remembered Adrian, as a very young child, challenging Durham with repeated “Why?” questions at the dinner table. At this, Durham, who, said Ethel, “was very unkind indeed”, reprimanded Adrian, whereupon Adrian got under the table and continued his “Why?” questions from there.6 Adrian’s older brother, Geoffrey, also retaliated against Durham, in his case by urinating in Durham’s bath out of hatred of him.

Unlike Geoffrey, it seems, Adrian courted Durham and succeeded, as a toddler, in transforming him from being “monosyllabic and very undemonstrative” into becoming “more affectionate”.7 Perhaps he missed Durham when he was away from home, including campaigning (unsuccessfully) as Liberal Party parliamentary candidate for Stepney in London in January 1906, and taking Ethel on exotic foreign holidays to Ceylon, Egypt, and Tunisia.

Ethel and Durham in Egypt, c.1907

Durham and Ethel consigned the care of their sons to a succession of nursemaids and governesses. At the age of three Adrian began sharing Philip’s and Geoffrey’s governess, Miss Drew, who ruled that if the boys’ “shoelaces came undone while out for a walk, there would be no jam for tea: if they came undone again, no cake as well”. Miss Drew particularly meted out this punishment to Geoffrey, for whom it seemed to be primarily designed. Adrian did not remember it happening to him albeit he continued into adulthood to be “entirely bad at tying laces or anything else”.8

By the time he was six Geoffrey, as well as Philip, had gone to boarding school. Geoffrey was sent to a naval cadet school, probably Osborne College on the Isle of Wight. And Philip, who initially attended a day school, King Alfred’s in Hampstead, was sent to boarding school preparatory to going to public school, Rugby. In their absence Miss Drew was dismissed after someone saw her “maltreating” Adrian in the park. His next “caretaker”, Miss Harley, used to sing him hymns. “She was for me the Salvation Army of morbid streets and morbid walks,” he recalled in also recalling himself, perhaps on account of his mixture of bullying and taking care of his less able brother, Geoffrey, as akin to the brother-murdering Cain in the Bible asking “Am I my brother’s keeper?” to which Adrian added: “That was a wicked, frightened joke of Cain’s.”9

Happier memories followed. He remembered himself, aged seven, admiring twelve-year-old Philip’s love of geology on a seaside holiday at Hythe. “Philip my eldest brother still asleep … Unravels stones with hammer, doesn’t chatter,” Adrian related from that time.10 He also remembered Miss Harley being replaced as his governess by “a Swiss, French speaking … fairly normal girl”, Mathilde. She was still with the family it seems when Durham, who had been seriously ill, was sufficiently recovered to watch through binoculars from a balcony at 18 Radnor Place the funeral procession for Edward VII pass along the nearby Bayswater Road.

“What stays in the mind were the long thin festive poles swathed in scarlet cloth, tipped with golden spear-heads that lined both sides of [the] Bayswater road. Even railings were tipped with gilt,” Adrian recalled from the coronation of George V the following June 1911. “The coronation brought soldiers to the park. Thousands were encamped there,” he also remembered. “Both Mathilde and I worshipped the soldiers,” he wrote.

For a time, I clung to military pomp and discipline as the “solution” of the park and its environs. I had tried to order the universe in earlier years by the array of my lead soldiers. I was inconsolable if one fell. And so, the face of the park came in part to be symbolized by a hybrid image of soldiers in scarlet jackets and Marble Arch orators standing on soap-boxes. At this time, too, Mathilde and I sought the press of the crowd, in Rotten Row on a Sunday morning or around the bandstand of a summer evening. I have a pictorial, almost Renoir-like image—the only one—of those times based, I have little doubt, on much later experiences. For it is night, a dark, still night with rain in the air. The speakers at Marble Arch are lit with their torches. The outer fringe of whispering couples are lit by the public lamps. The crowd where it is dense is dark. Hats are in outline, so too railings …11

Then, like his older brothers before him, Adrian, having started day school when he was seven, was sent away to prep school, Heddon Court in Cockfosters on the outskirts of London.

“Under the blare of King’s Cross [station] almost every boy is led by a parent far along the platform to be sick, sick from frightened anticipation, in front of the train that will throng him on an iron journey,” he recalled from the journey to Heddon Court.

London drags out along the route; against the will it begins to thin: less and less people live here as if a curse lay on the glowering land. In the semi-country at Barnet we stamp our way over a bridge that clatters; we take brake for the school. Masters are with us, a matron awaits. There will be a fire-practice tomorrow …12

He hated Heddon Court. He also hated Ethel for reneging on her promise to take him away if he disliked it.

Geoffrey, Philip, Durham, and Adrian, c.1913

He nevertheless did very well at Heddon Court. Encouraged perhaps by Philip’s interest in philosophy, he became precociously interested, aged eleven or twelve, in the philosophy of Immanuel Kant. Encouraged also by playing tennis with Philip it seemed possible that he might become a schoolboy champion. But this was thwarted by lack of tennis at Rugby where he first became a pupil in May 1916.

That month, Geoffrey, who had been called up a few months earlier for naval service in the First World War, served in a crow’s nest at the top of a ship’s mast during the Battle of Jutland. Several fires broke out on board his ship, HMS Malaya. There were heavy crew casualties. By the end of the battle, over 6000 fellow combatants were wounded or dead. Geoffrey survived but he was traumatised. Nevertheless, after his ship was repaired, he rejoined it before joining another ship, HMS George V, with which he served till after the end of the war when he was then sent on a course of instruction in Cambridge.

Meanwhile, in 1915, Philip won a place in his school rugby team and a scholarship to begin studying history and classics the following autumn at Queen’s College, Oxford. Then, after staying on at Rugby till Easter 1916, and after the institution that March of the Military Service Act making eighteen-year-olds liable for military conscription, he did army officer training and was then stationed as a qualified officer at Sheerness in Kent.

Geoffrey and Philip, c.1916

“It is a great comfort for me to know that you have habituated yourself into a state of calm … about everything. I have had to do the same, & am now without cares of any sort,” Philip wrote to Durham and Ethel after being sent in early January 1917 to Le Havre in France.13 In further letters home he asked after Adrian’s and Geoffrey’s wellbeing; he thanked Ethel and Durham for sending him food parcels from Fortnum & Mason in Piccadilly, and c...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title

- Copyright

- Dedication

- CONTENTS

- LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS

- ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

- ABOUT THE AUTHOR

- ABBREVIATIONS

- PREFACE

- PART I: CHILDHOOD AND YOUTH

- PART II: PSYCHOANALYSIS AND FAME

- PART III: OUTER AND INNER LIFE

- PART IV: PSYCHOANALYTIC AESTHETICS

- NOTES

- INDEX