- 368 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Development Anthropology

About this book

"Students will really appreciate this book. It has a rare combination of humor, clarity, exceptional writing, and, above all, a precision in outlining skills and knowledge for practice. As a professional, I learned much that will be useful to me." —Alexander M. Ervin, University of Saskatchewan "At last, a textbook on development anthropology that is comprehensive, clearly written, and up-to-date! Nolan provides an exceptionally useful framework for analyzing development projects, carefully illustrated with mini-case studies." —Linda Stone, Washington State University "Nolan's book should be a backpack staple for the practitioner of grassroots development." —Jan Knippers Black, Monterey Institute of International Studies Development Anthropology is a detailed examination of anthropology's many uses in international development projects. Written from a practitioner's standpoint and containing numerous examples and case studies, the book provides students with a comprehensive overview of what development anthropologists do, how they do it, and what problems they encounter in their work. The book outlines the evolution of both applied anthropology and international development and their involvement with each other throughout the latter half of the twentieth century. It focuses on how development projects work and how anthropology is used in project design, implementation, and evaluation. The final section of the book considers how both development and anthropology must change in order to become more effective. An appendix provides practical advice to students considering a career in development anthropology.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

Part One

anthropology and development

ANTHROPOLOGY NOT ONLY SHOWS US that there are different cultural worlds beyond our own; it helps us understand how to interact successfully with them. Encounters between the world’s diverse cultures occur daily, on a variety of different levels, but none are more important or significant than those relating to international development. This book examines how anthropology is used in those encounters.

Part One, “Anthropology and Development,” provides the background and framework for this examination by looking at anthropology, development, and the relation between them.

Chapter 1, “Anthropology as a Science of Discovery,” examines the discipline itself and what makes it special. Chapter 2, “The Rise of the Development Industry,” looks at the way in which international development began and evolved from its post-World War II beginnings. Chapter 3, “Putting Anthropology to Work,” focuses on the application of anthropology outside the university and specifically within the development industry.

Chapter 1

Anthropology as a Science of Discovery

A Different Way of Seeing

Anthropology enables us to discover the different cultural worlds that human groups create and inhabit, and to understand these worlds in terms other than our own. Anthropology helps us appreciate that each culture has its own distinctive ethos or worldview, each with its own logic and coherence. Anthropology therefore serves as a bridge across cultures, making one intelligible to the other, preserving the integrity of each.1

In the United States, anthropology has traditionally comprised four subdisciplines, or fields. Physical anthropology deals with human evolution and the biological aspects of contemporary human variation. Social or cultural anthropology focuses on contemporary human societies.2 Archaeology examines cultural history, and linguistics looks at language and how it is used.

Social and cultural anthropology, which form the focus of this book, have traditionally generated two principal products or outputs: ethnography, the detailed written description of part or all of a particular culture or society, and ethnology, the comparative analytical study of two or more societies in an attempt to derive patterns and build theory.

The Primacy of Culture

Culture is a central concept in anthropology. With minor variations, culture has a generally accepted definition among anthropologists; it refers to the distinctive, shared way of organizing the world that a particular group or society has created over time.3 This framework allows the members of that society to make sense of themselves, their world, and their experiences in that world—who they are, what they value, and where they are going in life. Culture provides groups with identities, ways and means, and ultimately destinations.

A human invention, culture has enormous implications for group evolution and survivaL The cultural patterns developed over generations of interaction enable a group’s members to organize their experience, make sense of it, and tell others what they know. Culture helps promote security and predictability in human affairs, thus freeing group members to be more productive and creative. Throughout history, culture has been instrumental in helping human beings adapt to—and influence—their surroundings. Groups value their culture, because it provides them with a way to structure their world, to give meaning to their experiences in that world, and to help them respond to events and circumstances. Cultures create different worlds, and just as people will protect their physical selves from assault, so too will they act, individually and collectively, to protect their symbolic selves—that is, their cultural worlds.4

There are three generally accepted components to culture: artifacts (the things we make), behavior (the ways we act), and knowledge (what we believe and know about the world). These facets of culture are manifest in every aspect of our lives. Often, all three are combined in particularly powerful symbols, such as a flag or a logo.

Culture is not static but dynamic and flexible. One of the most interesting things that anthropologists do is to look at the way in which groups and individuals manipulate their culture and its symbols in interactions, constantly negotiating or redefining cultural categories, meanings, and values.

Cultural Differences

All humans are fundamentally alike in some important ways: We share biological needs and functions, we use language, we form relationships. At the same time, however, each of us is a unique individual: No one else on earth has quite our particular collection of experiences, thoughts, and wishes.

Culture, however, groups some individuals together and excludes others; it makes some of us alike and some of us different in important ways. The way we dress, the gods we worship, the languages we speak, the food we eat, the things we value or despise—all of these are culturally derived, and serve to differentiate the members of one culture from those of another.

Such differences are learned. At birth, we are not American or Mexican or Japanese. As young children, we begin to acquire the framework of values, beliefs, and expectations that forms our cultural identity. As we gain experience with this framework, our behavior is reinforced by the people around us. By the time we are adults, our acquired culture is practically second nature to us.

So although we all develop distinctive individual personalities, we operate as individuals within our cultural framework. As Americans or Mexicans or Japanese, we use this framework to help us satisfy the same basic needs that all humans have, but in ways that are American, Mexican, or Japanese.

Across groups, cultural differences are immediately apparent in terms of the things people make (artifacts) and what they do (behaviors). Anthropologists, however, are particularly interested in the less visible aspects of culture that generate these observable differences. They pay close attention, therefore, to cultural knowledge—how members of a culture arrange their world, and what meanings and values people assign to aspects of that world.

People use their cultural knowledge to look at their surroundings and to organize what they see. They use their culture to arrive at judgments about what is happening in their world, to help them select appropriate responses to those happenings, and to draw conclusions about the results of these actions. Cultural knowledge is organized in complex but discernible patterns, and although these patterns are essentially arbitrary, they don’t seem arbitrary at all to the members of a particular society. Instead, they appear as logical, normal, right, and proper.

Cultures in Contact

As useful as culture is to us in many ways, it can also create problems. Although people everywhere must contend with many of the same issues in life—for example, life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness—they may define these things quite differently, and they will act to gain them in different ways.

Because we all grow up within a specific culture, its forms become almost second nature to us. Most people are unaware of their own cultural assumptions and biases and tend to take them for granted. Because our cultural frames of reference are so implicit, we tend to believe that the way our culture has taught us to see the world is the way the world really is. Anthropologists call this naive realism. “Pigs,” as one child explained, “are called pigs because they’re so dirty.”

Just as culture creates a “we” identity for us, it also creates a “they” category for everyone else. We deal with “them,” much of the time, through stereotypes: summary generalizations about other, culturally different groups. Although stereotypes can reduce the threat of the unknown by enhancing predictability, they are abstract and one-dimensional, and tend to obscure important information in new situations. If we apply stereotypes unthinkingly, we will eventually make serious mistakes. Not all American tourists overseas are loud and boorish, not all Frenchmen are charming, and not all English soccer fans are hooligans.

Culture also encourages individuals to be ethnocentric; to judge other cultures in terms of our own set of standards. An ethnocentric person assumes, in Shaw’s words, that “the customs of his tribe and island are the laws of nature.”5 Again, this can lead to mistakes in perception. What is different is not always inferior.

All this can make contacts between one culture and another potentially difficult. As we shall see, international development is, above all, a cross-cultural encounter.

How Anthropologists Work

The Ritual of Fieldwork

Although many disciplines engage in fieldwork, none do it as intensively as anthropologists, and the importance of fieldwork for both the discipline and its adherents cannot be overstated. Fieldwork is a true rite of passage, heavily invested with value. Students leave familiar surroundings for unknown places where strangers teach them new lore. When sufficient knowledge has been gained, the neophytes reenter their original community, but as profoundly changed individuals.

Many anthropologists consider their fieldwork experience as one of the defining moments of their life; as the time when they became aware not only of another culture’s significance, but of their own cultural premises and assumptions. Fieldwork also demonstrates one’s commitment to the discipline; surviving fieldwork and the ensuing dissertation is considered a test of one’s character, ability, and courage.

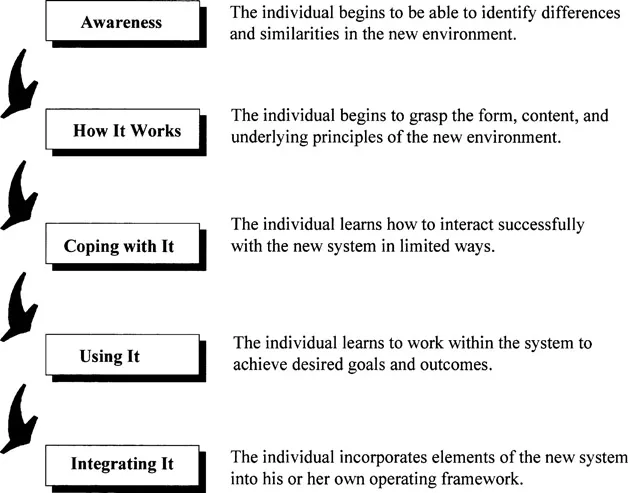

Figure 1.1 A Model for Cross-Cultural Learning

SOURCE: Nolan 1999: 25.

Today, anthropological fieldwork is done within corporations as well as in remote villages. Whatever the setting, the anthropologist’s goal is the same: to achieve an “out-of-culture” experience through immersion in another way of life; to transcend one’s own cultural boundaries and limitations, and see—really see—new worlds through the eyes of others.

In this sense, fieldwork is similar to other cross-cultural learning situations, and involves a set of linked stages of comprehension. Figure 1.1 sets these out.

Fieldwork takes time, luck, skill, and patience. A period of fieldwork will last anywhere from three months to three years, and it is not unusual for a doctoral student to stay in the field for a year or more gathering data for a dissertation. By remaining in the field for long periods of time and entering as fully as possible into the lives of the people around them, anthropologists are able to build up a many-layered picture of what is happening, uncovering facts and connections between facts that survey work might never reveal.

Fieldwork takes ...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title

- Copyright

- contents

- List of Illustrations

- Preface

- Acknowledgments

- PART ONE ANTHROPOLOGY AND DEVELOPMENT

- PART TWO DEVELOPMENT PROJECTS EXAMINED

- PART THREE THE WAY AHEAD

- Appendix: Becoming a Development Anthropologist

- Glossary

- References

- Index

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Development Anthropology by Riall Nolan,Riall W Nolan in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Social Sciences & Anthropology. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.