- 227 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

A leading critic and historian of nineteenth-century art and society explores in nine essays the interaction of art, society, ideas, and politics.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access The Politics Of Vision by Linda Nochlin in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Art & Art General. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

The Invention of the Avant-Garde: France, 1830–1880

“Art changes only through strong convictions, convictions strong enough to change society at the same time.” So proclaimed Théophile Thoré, quarante-huitard critic, admirer of Theodore Rousseau, Millet, and Courbet, an art historian who discovered Vermeer and one of the spokesmen for a new, more democratic art, in 1855, in exile from Louis Napoleon’s imperial France. Whether or not one agrees with Thore’s assertion, it is certainly typical in its equation of revolutionary art and revolutionary politics of progressive thought in the visual arts at the middle of the nineteenth century. Seven years earlier, in the euphoric days following the 1848 Revolution, a new dawn for art had been seriously predicated upon the progressive ideals of the February uprising. At that time the most important art journal of France, L’Artiste, in its issue of March 12, 1848, extolled the “genius of liberty” which had revived “the eternal flames of art” (obviously it had been less effective in reviving the rhetorical power of its writers), and the next week, Clement de Ris, writing in the same periodical, while slightly chagrined by the mediocrity of the first “liberated” Salon, nevertheless maintained that “in the realm of art, as in that of morals, social thought and politics, barriers are falling and the horizon expanding.” Even Théophile Gautier, certainly not an apostle of radicalism either in art or politics, took the opportunity to sing a hymn of praise to the new era in the pages of the same periodical. The ages of Pericles, Leo X, or Louis XIV were nothing, he maintained, compared to the present epoch. “Can a great, free people do less for art than an Attic village, a pope or a king?” The question, obviously, is rhetorical.

Delacroix was generally the painter to whom progressive critics looked for a fulfillment of the revolutionary ideals of the 1848 uprising; as early as March, Thoré, in Le Constitutione!, expressed the hope that Delacroix would paint L’Egalite sur les barricades de février as a pendant to his allegory of the revolutionary ideals of 1830, Liberty at the Barricades, which had been taken out of storage and placed on exhibition following the February uprising. Both Daumier and Millet entered the revolutionary government’s contest for a representation of the Republic, while Courbet, who toyed with this idea, also seriously considered taking part in the national competition for a popular song.

The very term “avant-garde” was first used figuratively to designate radical or advanced activity in both the artistic and social realms. It was in this sense that it was first employed by the French Utopian socialist Henri de Saint-Simon, in the third decade of the nineteenth century, when he designated artists, scientists, and industrialists as the elite leadership of the new social order:

It is we artists who will serve you as avant-garde [Saint-Simon has his artist proclaim, in an imaginary dialogue between the latter and a scientist]… the power of the arts is in fact most immediate and most rapid: when we wish to spread new ideas among men, we inscribe them on marble or on canvas. … What a magnificent destiny for the arts is that of exercising a positive power over society, a true priestly function, and of marching forcefully in the van of all the intellectual faculties …!1

The priority of the radical revolutionary implication of the term “avant-garde” rather than the purely esthetic one more usually applied in the twentieth century, and the relation of this political meaning to the artistic subsidiary one, is again made emphatically clear in this passage by the Fourierist art critic and theorist Laverdant, in his De la Mission de Vart et du role des artistes of 1845:

Art, the expression of society, manifests, in its highest soaring, the most advanced social tendencies; it is the forerunner and the revealer. Therefore to know whether art worthily fulfills its proper mission as initiator, whether the artist is truly of the avant-garde, one must know where Humanity is going, know what the destiny of the human race is…2

César Daly, editor of the Revue generale de ľarchitecture, used a similar military term, eclaireur, or “scout,” in the 1840s, when he said that the journal must “fulfill an active mission of ‘scouting the path of the future,’” a mission both socially and artistically advanced.3 Baudelaire, after a brief flirtation with radical politics in 1848—he had actually fought on the barricades and shortly after, in 1851, had written a eulogistic introduction to the collected Chants et chansons of the left-wing worker-poet Pierre Dupont, condemning the “puerile utopia of the art-for-art’s sake school,” praising the “popular convictions” and “love of humanity” expressed in the poet’s pastoral, political, and socialistic songs4—later mocked the politico-military implications of the term “avant-garde” in Mon Coeur mis à n% written in 1862–64.5

Certainly the painter who best embodies the dual implications—both artistically and politically progressive—of the original usage of the term “avant-garde” is Gustave Courbet and his militantly radical Realism. “Realism,” Courbet declared flatly, “is democracy in art.” He saw his destiny as a continual vanguard action against the forces of academicism in art and conservatism in society. His summarizing masterpiece, The Painter’s Studio[1], is a crucial statement of the most progressive political views in the most advanced formal and iconographic terms available in the middle of the nineteenth century.

Courbet quite naturally expected the radical artist to be at war with the ruling forces of society and at times quite overtly, belligerently, and with obvious relish challenged the Establishment to a head-on confrontation.6 The idea of the artist as an outcast from society, rejected and misunderstood by a philistine, bourgeois social order was of course not a novelty by the middle of the nineteenth century. The advanced, independent artist as a martyr of society was a standard fixture of Romantic hagiography, apotheosized in Vigny’s Chatterton, and he had been immortalized on canvas by at least two obscure artists by the middle of the nineteenth century; both of these paintings serve to remind us that there is no necessary connection between advanced social or political ideas and pictorial adventurousness. The sculptor Antoine Etex’s unfortunate Death of a Misunderstood Man of Genius (now in Lyons, one of the many crosses which French provincial museums seem destined to bear) was deservedly castigated by Baudelaire in his Salon of 1845, and is an obvious and derivative reference both to Chatterton and the dead Christ or Christian martyr.

1. Gustave Courbet, The Painter’s Studio, 1855, Paris, Musée d’Orsay

Somewhat more successful, because more concrete and straightforward, is an English variation on the theme of the artist as a social martyr, Henry Wallis’s Death of Chatterton, an overtly sentimental and marvelously detailed costume piece, praised by Ruskin in his 1856 Academy Notes as “faultless and wonderful.”7

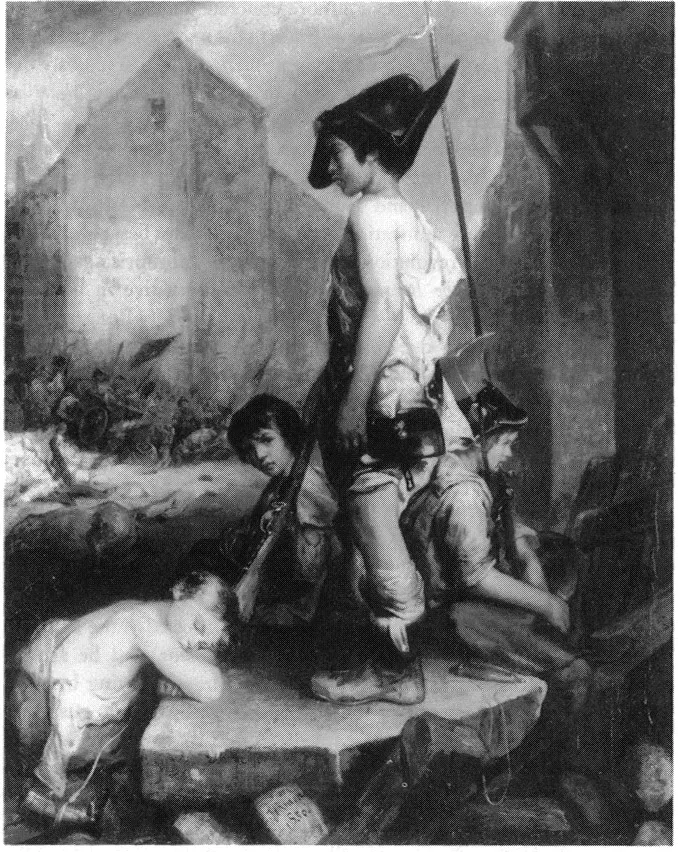

It is not until seven years after the 1848 Revolution that the advanced social ideals of the mid-nineteenth century are given expression in appropriately advanced pictorial and iconographic form, in Courbet’s The Painter’s Studio. Its truly innovating qualities are perhaps best revealed by comparison with the “revolutionary” painting of the uprising of 1830, Delacroix’s Liberty at the Barricades, a work conservative in both the political and the esthetic sense—that is to say, nostalgically Bonapartist in its ideology and heavily dependent upon mythological prototypes by Delacroix’s Neoclassical teacher, Guerin, for its iconography and composition.8 On the other hand, democratic and humanitarian passions seem to have been no more a guarantee of pictorial originality in the case of the Revolution of 1830 than they were to be in that of 1848. Although Philippe-Auguste Jeanron was far more politically radical than Delacroix, his The Little Patriots: A Souvenir of July 1830[2], which appeared in the 1831 Salon, is obviously a watered-down, sugar-coated reworking of Delacroix’s romantic, Molochistic allegory Greece Expiring on the Ruins of Missolonghi, which had been exhibited at the Musee Colbert in Paris in 1829 and 1830. Jeanron, a close friend of Thoré, was later named director of the National Museums under the 1848 Revolutionary Government, and he accomplished miracles of reorganization and democratization during his brief incumbency. Yet, as is so often the case, good intentions are no guarantee of innovating, or even memorable, imagery. Despite contemporary and localizing references in The Little Patriots, such as the dome of the Pantheon in the background or the paving-stone barricade to the left, the pall of the academic poncif hangs heavier over the painting than the smoke of revolutionary fervor; one is made all too aware, in the pose of the little patriot in the center—reminiscent of that of Donatello’s David, and so appropriate in its iconographic implications—that Jeanron was an art historian as well as an artist.

Certainly, there had been no dearth of paintings with socially significant, reformist, or even programmatically socialist themes in the years between the Revolution of 1830 and that of 1848. In 1835, Gleyre planned a three-part painting to be titled The Past, the Present and the Future,

2. Philippe-Auguste Jeanron, The Little Patriots: A Souvenir of July 1830, 1830, Caen, France, Musée de Caen

represented by, respectively, a king and a priest signing a pact of alliance; a bourgeois, idly stretched on a divan, receiving the produce of his fields and his factories; and The People receiving the revenues of all the nation. In the Salon of 1837, Bézard exhibited a social allegory, rather transparently titled The Race of the Wicked Rules over the Earth, and in the 1843 Salon, the versatile (or perhaps eclectic) Papety exhibited his controversial Dream of Happiness (now in the Musée Vivenel in Compiègne; see Figure 2, Chapter 9). In 1845, Victor Robert exhibited Religion, Philosophy, the Sciences and the Arts Enlightening Europe, while in 1846, no less a figure than Baudelaire himself deigned to notice the Universal Charity of Laemlein, a bizarre confection representing a personification of Charity holding in her arms three children: “one is of the white race, the other red, the third black; a fourth child, a little Chinese, typifying the yellow race, walks by her side.”9 Works such as these of course lent themselves perfectly to satire: both Musset and Balzac made fun of the ambitions of the apocalyptic and Fourierist painters, probably basing their caricatures on that learned and mystical pasticheur of universal panaceas, Paul-Joseph Chenavard.10

Yet one of these allegorical, socially progressive artists working prior to 1848 is worth examining more closely, if only to lend higher relief to the truly advanced qualities of Courbet’s postrevolutionary Studio: this is the little-known Dominique Papety (1815–1849), for a time one of Chenavard’s assistants, dismissed by Baudelaire in his 1846 Salon under the rubric “On Some Doubters,” as “serious-minded and full of great goodwill,” hence, “deserving of pity.”11 What is interesting about Papety is that he was a Fourierist, and Courbet’s Studio is among other things a Fourierist as well as a Realist allegory. Yet in the difference in conception, composition, and attitude between Papety’s allegory and that of Courbet lies the enormous gap between painting which is advanced in subject but conventional in every other way and that which is truly of its time, or even in advance of it (to use the term “avant-garde” in its most literal sense) and hence, a pictorial paradigm of the most adventurous attitudes of its era. Papety’s Fourierist convictions were stated in a language so banal that his Rêve de bonheur, although Fourierist in inspiration, looks almost exactly like Ingres’s apolitical Golden Age or Puvis de Chavannes’s Bois sacre; the elements identifying it with contemporary social thought are completely extraneous to the basic composition. While a critic of 1843 saw “a club, a people’s bank or a phalanstery” in “this dream of the gardens of Academe,” and noted the unusual amalgamation of Horace’s Odes and Plato’s Dialogues with the steamship and the telegraph, the expendability of these contemporary elements is revealed when L ‘Artiste announces that Papety, on the basis of critical advice, has replaced his steamboat with a Greek temple, “which,” remarks the anonymous critic, with unconscious irony, “is perhaps more ordinary but also more severe than socialism in painting.”12

The link—and the gap—between ...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title

- Copyright

- Contents

- LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS

- ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

- INTRODUCTION

- 1 The Invention of the Avant-Garde: France, 1830-1880

- 2 Courbet, Oller, and a Sense of Place: The Regional, the Provincial, and the Picturesque in 19th-Century Art

- 3 The Imaginary Orient

- 4 Camille Pissarro: The Unassuming Eye

- 5 Manet’s Masked Ball at the Opera

- 6 Van Gogh, Renouard, and the Weavers’ Crisis in Lyons

- 7 Léon Frédéric and The Stages of a Worker’s Life

- 8 Degas and the Dreyfus Affair: A Portrait of the Artist as an Anti-Semite

- 9 Seurat’s La Grande Jatte: An Anti-Utopian Allegory

- INDEX