- 512 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

"A must read for feminist activists, scholars, and policymakers. As this book amply demonstrates, women's movements around the world have much to learn from each other. The Challenge of Local Feminisms is the best place to start ... an inspiration and a challenge for us all." —Bella AbzugCochair, Women's Environment and Development Organization

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access The Challenge Of Local Feminisms by Amrita Basu in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Sozialwissenschaften & Genderforschung. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Topic

SozialwissenschaftenSubtopic

GenderforschungPart One

Asia

1

Discovering the Positive Within the Negative: The Women's Movement in a Changing China

ΝAIHUA ZHANG WITH WU XU

THE JANUARY 1988 ISSUE of Women of China, the leading Chinese official women's magazine, published a letter written by Li Jing, a woman worker who had lost her position as part of her enterprise's efforts to increase productivity and profit.1 After losing her position, she earned only 80 percent of her previous salary and no bonus, which affected the living standard of her family, and she felt humiliated after being dismissed as redundant labor. In her letter Li wondered why economic reform had brought bitterness to women like her, making them appear undesirable employees just because they had to shoulder heavier child care and housekeeping burdens. She asked, "Where is my way out, where is equality?" In response to her letter, the magazine initiated a nationwide, year-long discussion entitled "1988: Where Is the Way Out for Women?" It covered topics such as gender equality, female labor force participation, the social welfare system, and women's interests versus the state's interests in economic reform.

This incident took place amid a growing urban women's movement in the People's Republic of China (PRC), highlighting its focus on women's enthusiasm for and frustration with recent economic reform; a reexamination of past experiences, including the legacy of the Chinese Communist Party's (CCP) theory and practice as they relate to women's issues; the awakening awareness of women as an

China

General

- type of government: State socialist

- major ethnic groups: Han Chinese (94%); 56 other recognized minority groups

- language(s): Mandarin; Cantonese; regional languages

- religions: Officially atheist; Confucianism; Taoism; Buddhism; Muslim minorities; some Christians

Demographics

- population size: 1.151 billion

- birth rate {per 1,000 population): 22

- total fertility (average number of births per woman): 2.0

- contraceptive prevalence (married women): 83%

- maternal mortality rate (per 100,000 live births): 115

Women's Status

- date of women's suffrage: 1949

- economically active population: M 87% F 70%

- female employment (% of total workforce): 43

- life expectancy M 69 F 72

- school enrollment ratio F/100 M)

| primary | not avalible |

| secondary | not avalible |

| tertiary | not avalible |

- literacy M 87% F 68%

independent group; and women's determination and desire to find organized solutions to the problems they face as they continue their struggle.

The current women's movement emerged with China's 1979 economic reforms, which led to a more diversified economy as well as to more relaxed political, social, and intellectual climates that allowed for the expression of a variety of interests, including those of women. Two major factors shaped the development of the new women's movement. The first was a response to the problems women faced. The second was an intellectual effort to understand the position of women in Chinese society. The majority of the participants in this new movement are urban intellectual and professional women from governmental and nongovernmental organizations (NGOs). They have collaborated and clashed in their efforts to define and articulate women's demands and to fight for women's interests. While the movement is deeply rooted in and is part of the national effort to reform the country, women seek a more independent identity for themselves and their movement. It is marked by women's initiative and spontaneity from the bottom up

In this chapter we aim to provide a snapshot of the movement and to shed light on the development of Chinese feminism. We touch on the relationship between women and a party/state that claims women's liberation as its mandate, and we show how this specific context poses a challenge to the women's movement of combining a top-down and a bottom-up strategy. We want to reveal the complicated legacies of Marxism to and the CCP's impact on the women's movement. As a Chinese woman remarked, "There is something negative within the positive, positive within the negative."2 It is in addressing issues left from China's traditional and revolutionary past and responding to challenges emerging in the current reform that today's women's movement is shaping a new future for women and for China as well.

We define a women's movement as an active, organized effort by a nation's women to promote gender equality and the advancement of women's interests. It is marked by the basic characteristics of other social movements, such as shared ideology, organizations, and organized activities on a scale that affects not only the individuals involved but also society as a whole. Some Chinese scholars also emphasize that a women's movement should be initiated and led "by women," designed "for women," and result in raising women's consciousness—to distinguish a women's movement from a movement organized by the state, not directly for women per se, that brings about a "liberating effect" on women.3 Thus, while scholars and women activists agree that China is witnessing a women's movement that started in the 1980s, they disagree about the relationship between today's women's movement and past women's activities as well as the implications of the legacy of the CCP on the "woman question."

History and Legacy

Prerevolutionary China: From the Turn of the Century to 1949

China's first modern women's movement developed alongside the country's political movements.4 The issue of women was initially brought to public attention by male advocates during the reform movement of the mid-i890s. Women's plight, their ignorance because of their exclusion from education, and their bound feet symbolized a nation weakened by the assault of foreign powers and the traditional rule of the decaying Qing dynasty. While a small number of elite women's organizations had appeared by the turn of the century, recognition of women as a social category, broad attention to women's problems, and large-scale organized women's activities grew out of the 1919 May Fourth Movement.5 This movement attacked traditional culture and Confucian ideology as well as oppressive family and marital institutions. (Confucian influences, having shaped many social institutions, had also helped define gender relations.) The movement was also patriotic and anti-imperialist, and it signaled the rise of a socialist movement in China.

During the 1920s, an urban-based women s movement appeared, pushed by women students, professionals, leftist women activists, and industrial women workers. During the first national alliance between the Guomindang (GMD) and the CCP (1924-1927), women campaigned to include their organizations at the First National Congress held by the GMD. They also rallied support for the Northern Expedition aimed at destroying warlord power to unify China as a national republic. It was also during this period that rural women were first mobilized amid the rising peasant movement, especially in places the Northern Expedition swept through. Women took off their foot-binding bandages and defied and opposed local customs and clan practices that discriminated against or persecuted women. They were further drawn into political and social activities in the CCP base areas by the party's effort in rural organization after it was forced out of cities in 1927 by the GMD. Urban women activists were mobilized again in the mid-i930s to combat a regressive move to push women back into the family. Anti-Japanese resistance brought another resurgence of women's organizations throughout the country. New coalitions were once more established among women's groups to support the resistance effort and to promote women's interests during the second alliance between the GMD and CCP.

In retrospect, this context encouraged the development of a modern feminism in China that differs from that of the West. Radicalized by the impact of imperialism in China's coastal cities, and particularly by the patriotic explosion associated with the May Fourth Movement, many intellectual women, despite the influence of Western individualism, switched their earlier emphasis on personal autonomy, dignity, and individual liberation to liberation of the collective. These women chose a political, as opposed to a literary, sexual, or individual, path to liberation.6 Thus, the liberation of women as part of the national struggle for independence was the dominant strategy of the women's movement in pre-1949 China.

The two goals of national independence and gender equality were not the same but could not be separated. In the context of the anti-imperialist, anti-Confucian movement, women's rights became a cause linked with, yet subordinated to and defined by, the interests of the nation.7 While the notion of female emancipation based on Western feminist ideas was embraced by some elite Chinese women, it did not "survive as [a] viable alternative to the Marxist categories of class-bound liberation" because of the prominent role played by women workers and rural women under the direction of the CCP during its rise to power in 1949.8 The CCP, gaining legitimation through its leading role in the anti-Japanese resistance, also cast a strong influence on women who were responding to its patriotic messages and built their movement in that context.

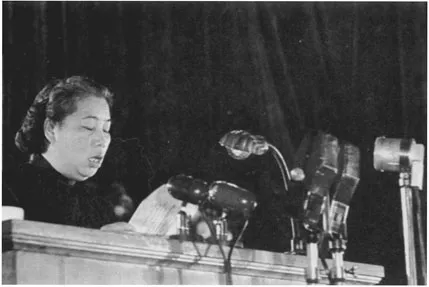

Chinese communists viewed women's liberation as a necessary and inevitable part of socialist revolution. Partisans and members of the People's Liberation Army greet each other in 1949.

Postrevolutionary China: 1949–1978

The CCP's theoretical framework on the woman question is based on Marxist, nationalist, and May Fourth feminist discourse.9 It links women's oppression to the rise of private ownership and class society and views women's liberation as a necessary and inevitable part of socialist revolution. The CCP's organizational relationship to women is also shaped by its theory and practice of the mass line, a working philosophy and leadership style initiated by Mao Zedong to maximize enthusiasm and participation of the people in the revolution. Mass organizations were established to act as an intermediate structure to connect society to the party/state.

The All-China Women's Federation (ACWF) was set up in 1949 on the foundation of women's associations established in the years 1937-1945 in the anti-Japanese base areas and women's organizations in the GMD-occupied cities that worked closely with the CCP during the anti-Japanese war and the civil war.10 The ACWF quickly established branches throughout the country as the mass organization designated to mobilize and represent Chinese women. Since there was no government department in China in charge of women's affairs, the ACWF had the authority and resources to help interpret and implement state policy on women. As of 1994, it had over ninety-eight thousand full-time cadres on the state payroll. In contrast with government organs, it has no administrative or legislative power, and its functions rely heavily on hundreds of thousands of grassroots activists throughout the five-tier system from the village to the center. This allows the ACWF to reach millions of women. It officially incorporates women into mainstream CCP politics and social structure. Women enter the mainstream political structure as members of a mass group whose biologically based membership makes them a constituency with special concerns and needs. Yet like other mass organizations whose group interests are subordinate to those of the state,11 the ACWF does not exist only to make special gender-based demands. The gender interests of women are often downplayed when there is a conflict in interests between women and the state.

Hsu K'uang-P'in, vice president of the All-China Women's Federation (ACWF), speaking at a meeting in Moscow in November 1949, the year the ACWF was founded.

The ACWF was to act as a bridge, a two-way channel of communication, between women and the party/state and a vehicle for the mobilization of women in the service of party goals. As the new government sought to undermine important elements of the old social order, it attacked aspects of patriarchy associated with the system of marriage. Following the Marriage Law of 1950, the party launched the single most important mobilization campaign directly targeting women's issues as a means to attack what it designated as the feudal elements of former marriage practices, such as forced marriage and bride-price. This was the first in a series of events that significantly improved women's lives and raised their status in society. Consciousness-raising among women was adopted by the ACWF to make women see that they had been oppressed under feudalism and that the new society would bring them liberation and equality with men. The CCP's ideas about women's liberation became the ideology of the women's movement, which subsequently subordinated the independent interests of women to state policy; this marked the beginning of women as a state product.

Women's programs were all state induced from the top down. However, women were not passive recipients. Many, especially young workers and peasants who were the main beneficiaries of state programs on women, embraced party policy, believing that their liberation would come from submitting their interests to those of building socialism in China. The ACWF, at the time a united front organization including non-CCP women advocates and activists groups,12 pushed for progressive policies for women. It grew rapidly, serving as a s...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title

- Copyright

- Dedication

- Contents

- Foreword

- Acknowledgments

- Introduction

- Part 1: Asia

- Part 2: Africa and the Middle East

- Part 3: Latin America

- Part 4: Russia, Europe, and the United States

- Selected Bibliography

- About the Book and Editor

- About the Contributors

- Photo Credits

- Index