eBook - ePub

Everyday Irrationality

How Pseudo- Scientists, Lunatics, And The Rest Of Us Systematically Fail To Think Rationally

- 240 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Everyday Irrationality

How Pseudo- Scientists, Lunatics, And The Rest Of Us Systematically Fail To Think Rationally

About this book

Robyn Dawes defines irrationality as adhering to beliefs that are inherently self-contradictory, not just incorrect, self-defeating, or the basis of poor decisions. Such beliefs are unfortunately common. This book demonstrates how such irrationality results from ignoring obvious comparisons, while instead falling into associational and story-based thinking. Strong emotion—or even insanity—is one reason for making automatic associations without comparison, but as the author demonstrates, a lot of everyday judgment, unsupported professional claims, and even social policy is based on the same kind of "everyday" irrationality.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Everyday Irrationality by Robyn Dawes in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Social Sciences & Sociology. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

Irrationality Is Abundant

This book analyzes irrationality. First, it specifies exactly what types of conclusions and beliefs deserve the term irrational; second, it examines the structure of irrational conclusions; third, it provides examples from everyday life, from allegedly expert opinion that is not truly rational to beliefs that most of us would immediately recognize as irrational—such as those we associate with psychosis or lunacy The book will first clearly delineate the difference between an irrational belief or conclusion and one that is simply poor. A conclusion or belief may be poor because it is ill considered, is not in accord with our purported best interests, or is simply dumb.

In this book, I define irrationality (irrational conclusions or beliefs) as conclusions or beliefs involving self-contradictions. Consider the simple example from the preface. A psychotic woman believes that she is the Virgin Mary because she is a virgin. Her belief involves a clear contradiction, because this woman simultaneously acknowledges that other people are virgins, but that she herself uniquely is the Virgin Mary. (An argumentative person might claim that we have not established the self-contradiction until we add an additional premise that the Virgin Mary cannot refer both to a unique person and to a multitude of people simultaneously; in the analyses that follow, I will assume that the reader accepts such "obvious" implicit premises as valid and capable of being assumed.) At a more sophisticated level, a purported expert in court might claim that someone must be schizophrenic because she gave a typical schizophrenic response to a particular inkblot on the Rorschach test. That conclusion would be rational only if no one who wasn't schizophrenic would give such a response, just as the psychotic woman's conclusion would be rational if everyone who wasn't the Virgin Mary was not a virgin. Because of content and source, however, we are not as quick to recognize the irrationality of the expert as we are to recognize the irrationality of the psychotic woman.

Besides considering conclusions irrational because they are self-contradictory, we will also consider the thinking process that is "one step away" from conclusions. If the thinking process yields an irrational self-contradiction when followed to a natural conclusion, then this process is irrational as well. Consider, for example, a head of a depression unit at a major psychiatric hospital (this is a real example that I was made aware of, not a hypothetical one). He wishes to find out what depressives are like, but proudly proclaims that he has no interest in finding out what people who are not depressed are like. Well, depressives brush their teeth in the morning (admittedly an unpleasant activity that may lead to a brief moment of depression), as do most other people. Here, the self-contradiction lies not in the conclusion itself that tooth brushing is a defining characteristic of depressives (a sufficiently absurd conclusion that few would make), but in the failure to make an obvious comparison in reaching structurally similar conclusions. That type of noncomparative reasoning can be characterized as irrational, even if it stops short of the final assertion to which it leads.

This book attempts to combine two distinct types of analyses, which are generally presented in different books. The first is an analysis of irrationality that is as specific as possible, that is, an analysis of the exact structure of self-contradictory belief or reasoning. Thus, it might be considered a text in logic or philosophy (or, because a lot of it involves probabilistic reasoning, in statistics). Combined with this analysis, however, will be examples from everyday life, from bogus professional opinion ("junk science"), and occasionally from individual or group pathologies (e.g., belief in widespread satanic cults that not only abuse children sexually but make them eat small babies who have been specially bred for that purpose). Unfortunately, there are many irrational conclusions and beliefs in our culture from which to choose. Those analyzed at some length—and as precisely as possible—are those with which I am most familiar. With public opinion polls indicating that more people in the United States believe in extrasensory perception than in evolution, it is not surprising that examples abound.

I use the term "irrationality" in the manner that is developed in the logical analysis of what constitutes that term. Often, in commenting on social conclusions and policies, people characterize conclusions with which they disagree as irrational. Some conclusions are. Thus, we can occasionally agree with our favorite editorial writers when they declare the opposition's views irrational. But often, conclusions can be just incorrect, or they may be poorly supported, or they may be well supported although critics (or we) may not realize that. Differing views of social conclusions and policies, however, are often not just a matter of opinion. Sometimes, there is very little way of evaluating the validity of one view or an opposing one. But at other times certain policies really are based on irrational reasoning and conclusions. The point of this book is to explain exactly what constitutes such irrationality and to show how it occurs in selected social contexts.

To summarize, the definition of irrationality that I propose here is that it involves thinking in a self-contradictory manner. The conclusions it generates are also always false, because conclusions about the world that are self-contradictory cannot be accurate ones. We all accept the simple idea that what is logically impossible cannot exist. But what, in turn, yields the self-contradiction? The answer proposed in this book is that the contradiction results from a failure to specify "obvious" alternatives and consequently a failure to make a comparative judgment involving more than one alternative. In the context of reaching a statistical conclusion, we fail to compare the probability that an observation or a piece of evidence results from one possibility with the probability that it results from another. What is a "reasonable" alternative? We can never be absolutely sure that we have thought of all of them, but in the examples presented in this book, the nature of these alternatives is clear—at least when they are specified.

Specifying as many clear alternatives as possible yields another general principle: We can generally recognize important alternatives and hence correct irrational conclusions when these alternatives are made clear. The problem is that we ourselves often do not generate enough alternatives and hence do not reach the rational conclusion. Thus, a failure of rationality is what can be termed a performance problem, not a competence one. The analogy with grammatical language is clear. We often do not speak grammatically, but we can recognize a grammatical problem when it is pointed out to us (meaning our grammatical competence is greater than our grammatical performance).

I will illustrate the meaning of "clear contradiction" with a striking finding in the medical decision-making literature. In this example, people are reasoning in such a way that they conclude that alternative A is preferable to alternative B but at the same time that alternative B is preferable to A. This example also illustrates the difference between a poor decision and an irrational one.

A Medical Decision-Making Example

Consider the problem of choosing between surgery and radiation as treatment for lung cancer in a sixty-year-old person. Some doctors may believe that they themselves know which treatment is better for their patients, and many of their patients may believe in following "doctor's orders." We might do a statistical analysis of survival rates and decide that some of these doctors are very wise in their recommendations ("orders"), whereas others are not very wise, or are managing some of their patients inappropriately.

Alternatively, it is possible to engage in a so-called utility analysis with the patients themselves, to find out the nature of their real values and their wishes for surviving certain amounts of time in certain physical conditions. As a result, it is possible to claim, for example, that what is best for a particular patient is radiation; again, if either the patient or doctor chose surgery instead, we might conclude that an error had been made, that the decision was a poor one. The utility analysis might provide the "end values" of the patient involved, and the conclusion might be that radiation is the best means of achieving those ends. Some economists and other theorists would therefore claim that a decision to do surgery instead might be considered not rational, thereby broadening the definition of irrationality used here to include a means/ends analysis that concludes that the action chosen is or is not the best—or at least a satisfactory—means for achieving the desired ends. This more inclusive definition of rationality or irrationality will not be adopted here. We would only use the broader definition if we could thoroughly analyze all sorts of factors concerning what people really want and how various courses of action may or may not satisfy these wants. Reaching a poor conclusion from such an analysis is quite different from ignoring an obvious alternative (e.g., that one should consider whether nondepressed people brush their teeth) and consequently reaching a self-contradictory conclusion. In this book, the latter, more restrictive definition of irrationality will be adopted. Thus, there is a gap between a belief or decision that is irrational and one that is simply not very good—as defined by failure to achieve implicit or explicit goals in an optimal or satisfactory manner.

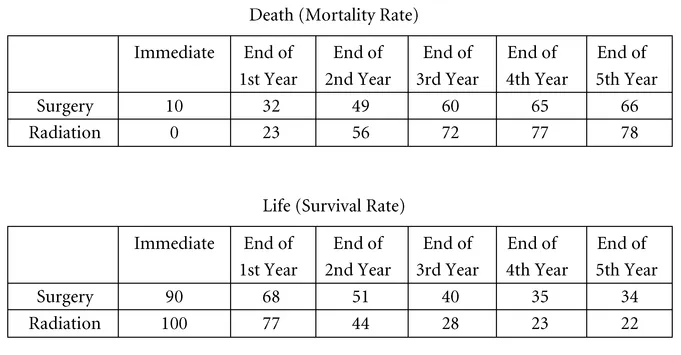

To appreciate this gap, consider the present medical decision-making context in which the patients themselves are often asked to choose between radiation and surgery—after they have been "fully informed" of the probable consequences of each type of treatment. A reasonable way of informing these patients would be to inform them of the likelihood that patients of their age would die immediately given each treatment, would die before the end of one year given each treatment, and so on. Figure 1.1a presents such information as of 1980 for sixty-year-old patients receiving either surgery or radiation as the treatment for lung cancer. Under surgery there is a 10 percent chance of immediate death (during the operation), a 32 percent chance of death before the end of the first year, a 49 percent chance before the end of the second year, and so on, up to a five-year mortality rate of 66 percent. In contrast, radiation yields a zero percent chance of death immediately, a 23 percent chance of death before the end of the first year, a 56 percent chance before the end of the second, and so on, up to 78 percent mortality by the end of the fifth year. Alternatively, we could present the information by pointing out that surgery involves a 90 percent chance of immediate survival, a 68 percent chance of survival by the end of the first year, and so on. The information is presented both ways in Figure 1.1a.

FIGURE 1.1a A numerical representation of the choice between surgery and radiation for hypothetical sixty-year-olds with lung cancer, with the probabilities of living and dying shown separately. From McNeil et al., 1982.

What did the potential patients and doctors and ordinary people choose under these circumstances? Presenting the information in terms of death favors radiation; presenting it in terms of life favors surgery. Note what happens. The difference between a 10 percent chance of immediate death versus no chance at all is quite striking, and as we look down the road, the differences seem less striking. Moreover, by the end of the third year, there is a more than 50 percent chance of death with either treatment, anyway. On the other hand, when we look at life rather than death, the difference between 100 percent chance of living and 90 percent is not as salient as some of the later differences—which are 12 percent or so by the end of the third, fourth, or fifth year. The unsurprising result is that presenting the choice in terms of the likelihood of death favors radiation, whereas presenting it in terms of the likelihood of life favors surgery.

The irrationality arises because the probability of life is just 1 minus that of death, and vice versa. The choices are identical. Whether we think of probabilities abstractly or in terms of relative frequencies, most of us understand that these choices are identical, because the probability of living is just 1 minus the probability of dying, and vice versa. We can infer the contradiction from the fact that when separate people are presented with tine choice in these two different frames, the proportion of choices of radiation in the death frame plus the proportion of choices of surgery in the life frame exceeds 100 percent. Because people were randomly assigned to make a judgment in the life frame or the death frame, we can conclude that individual people as well will make contradictory choices (although, of course, they might realize the contradiction when they are presented with both frames at once). In fact, it is possible to get a contradiction when a single individual is presented with these two types of frames (in other contexts) just a few questions apart. When confronted, the subjects realized that they had made contradictory choices and changed about half the time, but otherwise told experimenters, "I just can't help it." (See Dawes, 1988, pp. 36–37, for a discussion of this work by Scott Lewis.)

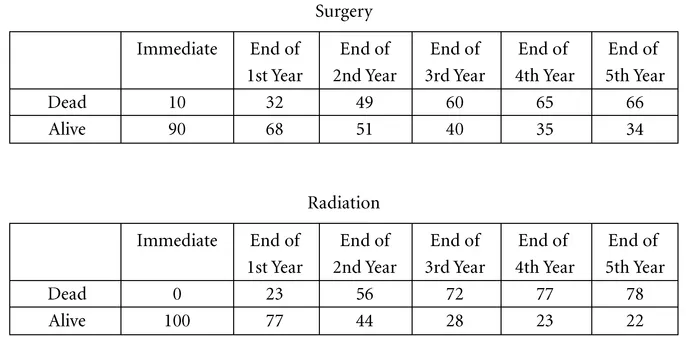

FIGURE 1.1b A numerical representation of the choice between surgery and radiation, with the probabilities of living and dying shown together. From McNeil et al., 1982.

That dying and surviving are simply two ways of stating the same possibility is illustrated in Figure 1.1b. Here the course of life after radiation or after surgery is indicated by both the probability of living and the probability of dying (despite the redundancy of listing both probabilities).

Amos Tversky and Daniel Kahneman, who were among the first to examine such framing effects systematically, recommended that when they occur, people be presented with choices in both frames (Tversky and Kahneman, 1981). Considering the "I just can't help it" confusion found by Scott Lewis, however, I am concerned that such double framing may yield more confusion rather than less.

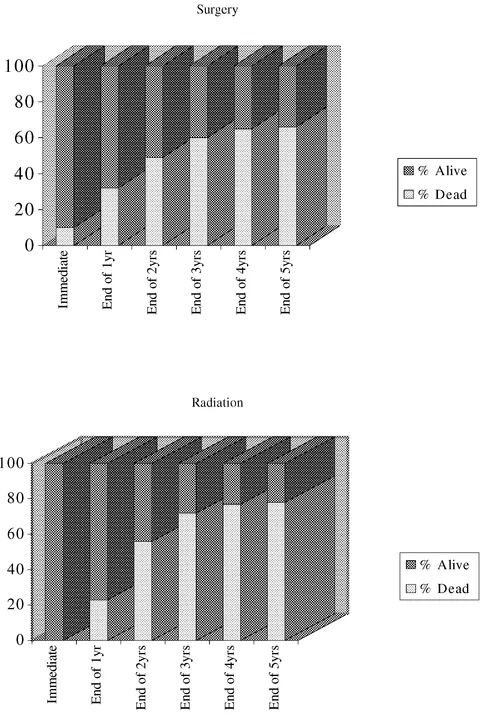

FIGURE 1.1c A visual representation of the choice between surgery and radiation, with the probabilities of living and dying shown together. From McNeil et al., 1982.

One alternative possibility is not to use words at all, but to use visual illustrations, or graphs. In a bar graph, for instance, part of a column represents the probability of death, and the remainder, naturally, represents the probability of life (Figure 1.1c). Even here, however, we might worry about how the alternatives are presented, for example, solid versus dashed spaces, and which alternative is at the base of the graphic representation (here death) and which at the upper part. I recommend black for death and green for life in a colored version of such a graph.

To summarize, making one decision when the alternatives are phrased in terms of living and another when they are phrased in terms of dying is irrational—given that we all recognize, at least implicitly, that the relative frequency of living is 1 minus the relative frequency of dying, and vice versa. Again, we have been presented with the same information in each frame, and we reached a di...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title

- Copyright

- Contents

- Preface

- Acknowledgments

- 1 Irrationality Is Abundant

- 2 Irrationality Has Consequences

- 3 Irrationality: Emotional, Cognitive, Both, or Neither?

- 4 Irrationality as a "Reasonable" Response to an Incomplete Specification

- 5 Probabilistic Rationality and Irrationality

- 6 Three Specific Irrationalities of Probabilistic Judgment

- 7 Good Stories

- 8 Connecting Ourselves with Others, Without Recourse to a Good Story

- 9 Sexual Abuse Hysteria

- 10 Figure Versus Ground (Entry Value Versus Default Value)

- 11 Rescuing Human Rationality

- Index