- 256 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Congress And The Decline Of Public Trust

About this book

Since the late 1960s, trust in government has fallen precipitously. The nine essays composing this volume detail the present character of distrust, analyze its causes, assess the dangers it poses, and suggest remedies. The focus is on trust in the Congress. The contributors also examine patterns of trust in societal institutions and the presidency, especially in light of the Clinton impeachment controversy. Among the themes the book highlights are the impacts of present patterns of politics, the consequences of public misunderstanding of democratic politics, the significance of poll data, and the need for reform in campaign finance, media practices, and civic education.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Congress And The Decline Of Public Trust by Joseph Cooper in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Politics & International Relations & Politics. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

The Puzzle of Distrust

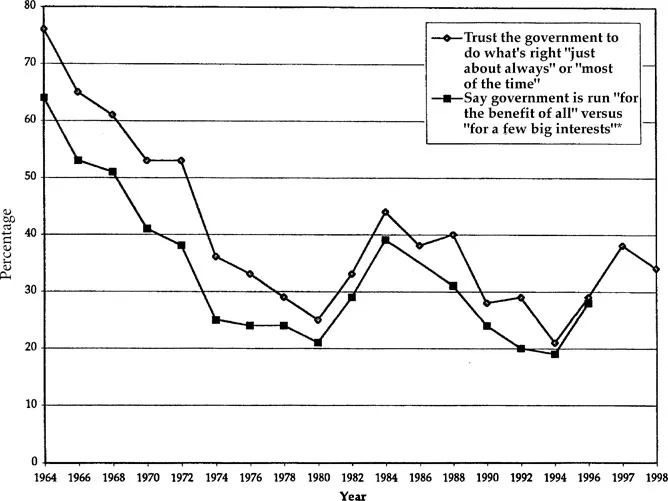

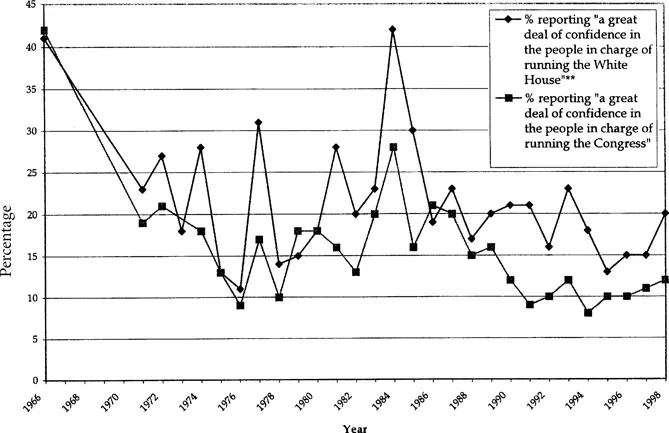

There is no issue in American politics that is more difficult to unravel, or more significant for the future of representative government in the United States, than the issue of public trust. In recent decades cynicism and suspicion regarding the processes of democratic government and the officials elected to operate them have been deep and pervasive in the United States. Most ordinary citizens do not trust public officials to act responsibly and effectively in the service of the public interest. They do not believe that public officials care about or respond to their views, and many doubt their fundamental honesty. Bill Bradley’s analysis in the Foreword of the low state of trust in government and politicians in the United States eloquently captures prevailing public attitudes and is amply supported by a variety of recent surveys, articles, and books. Similarly, John Hibbing and Elizabeth Theiss-Morse’s characterization of Congress as a “public enemy” in a recent work (1995) provides an apt metaphor for the public’s low regard for Congress and is also amply supported by a number of surveys and other scholarly works. Figure 1.1 presents results on two frequently asked survey questions to illustrate the sharp and persistent drop since the late 1960s in the trust that ordinary citizens have in the representativeness, integrity, and effectiveness of government. Figure 1.2 presents results on two popular and repeated survey questions that pertain more specifically to the premier political institutions of the national government. It clearly indicates that the decline of trust in government has been accompanied by declining trust in the leadership of the Congress and the presidency.

Issues and Goals

The depth and persistence of low levels of trust in government and in key political institutions provide substantial grounds for concern over the fate of representative government in the United States. Even markets, which rely simply on the clash of self-interest as their primary ordering principle, cannot work effectively without trust in the enforceability of contracts and the value of money. Representative government, which must not only rely on the clash of self-interest but also seek to regulate and even transcend it, has far more stringent requirements. Trust in the fundamental purposes and design of the political system, in the representativeness and integrity of its decisionmaking structures and processes, and in the ability of government to produce policies that satisfy citizen needs is essential, in all these regards, to the maintenance of a viable democratic order.

Figure 1.1 Trust in Government

* Question not asked in 1986.

SOURCE FOR 1964-1996 data: American National Election Studies; source for 1997 and 1998 data: Pew Research Center for the People and the Press.

Nonetheless, current evidence regarding low levels of public trust needs to be placed in historical and comparative perspective. Distrust of politics and politicians in the United States is nothing new. It rather has been a continuing feature of American politics from the eighteenth century to the present (Huntington, 1981). We may note, for example, that in the pre-Civil War period one article in the North American Review complained that Congress was “the most helpless, disorderly, and inefficient legislative body that can be found in the civilized world,” and another observed that in Washington politicians were publicly bought and sold “like fancy railroad stock or copper mine shares” (White, 1954, pp. 26-27). In the post-Civil War period Henry Adams (1931) wrote that “the

Figure 1.2 Trust in the Congress and the Presidency

NOTE: No poll taken in unmarked years. In 1966, 1971, 1972, and 1975, the first question refers to confidence in “the people in charge of running the executive branch of government.” Comparable results were achieved in years when both wordings were used, although scores for “the White House” were usually slightly higher than for “the executive branch of government.”

SOURCE: Harris

grossest satires on the American Senator and politician never failed to excite the laughter and applause of every audience. Rich and poor joined in throwing contempt on their representatives” (p. 272). In the same period Mark Twain called congressmen the only “native American criminal class” (Kimball and Patterson, 1997, p. 702). In the early decades of the twentieth century Woodrow Wilson argued that the government of the United States was “a foster child of special interests” (Green, Fallows, and Zwick, 1972, p. 29). In the years between the two world wars Will Rogers described Congress as the best that money can buy, and a lead article in the American Mercury was titled “Why All Politicians Are Crooks” (Green et al., 1972; Wilson, 1951). As a final example, less than two years after the end of World War II, George Gallup wrote that “the public sickens and turns its head away from the very thought of politics” and “would rather see their children work as street sweepers than besmirch themselves in politics” (Wilson, 1951, p. 242). Nor does history provide the only testimony to the fact that distrust in American democracy is a complex problem, not a simple one. A recent Pew Research Center survey (1998a) that compares distrust in the United States and stable Western European democracies reveals some striking similarities, strongly suggesting that stable democratic orders invariably blend elements of trust and distrust.

The character and consequences of public trust in American democracy thus pose a puzzle that we are a long way from solving (Nye and Zelikow, 1997). If trust is required in the policymaking capacity, institutional processes, and fundamental design of the American political system, the persistence of distrust throughout American history raises the question of the degrees of trust that are required in all these regards. This question, in turn, raises two farther questions: What are the relationships between the different types or components of trust? And what determinants govern these relationships, both inside the political system and between the political system and the broader society? These are extremely difficult issues to analyze and assess. Nonetheless, they are questions that must be addressed. Despite the fact that distrust is no stranger to American government, current levels of distrust in politics and politicians in the United States are difficult to discount. The American political system is clearly in no imminent danger of demise, but the rampant cynicism and suspicion that have characterized American politics since Vietnam and Watergate provide dramatic evidence of factors and conditions that may well threaten the long-term viability of American democracy. It is thus no accident that the problem of distrust has attracted widespread attention among pollsters, scholars, and the press (Hibbing and Theiss-Morse, 1995).

Pollsters have been asking questions that bear on public trust for more than half a century. Over time, and particularly since the 1970s, the scope and depth of these surveys, the number of polling organizations involved, and the continuity of inquiry have increased greatly as survey research has become professionalized and institutionalized and as the stark characteristics of distrust in politics and politicians have been revealed (Bowman and Ladd, 1994; Lipset and Schneider, 1987). The chapters of this volume often draw on the large body of data that have been gathered; a summary of the most salient features of these data is presented in the Appendix. Similarly, while congressional scholars since the 1960s have been concerned with explaining why public confidence in Congress is low, treatments of distrust in governmental decisionmaking generally, in major political institutions, and in other sectors of society have mushroomed in the 1980s and 1990s (Durr, Gilmour, and Wolbrecht, 1997). As can be seen from the references cited in the chapters of this volume, a host of books and articles have been published by a broad mix of academics, working journalists, pollsters, and political commentators. The chapters in this book are informed and instructed by this work, as well as by polling data.

The goal of this volume is to advance our understanding of the character, causes, and dangers of distrust in modern American politics and to consider the merits of possible remedies. In pursuing this goal, we focus our analysis at the national level, with emphasis on distrust in Congress because of the pivotal role that Congress plays in the success and viability of representative government in the United States. As the long history of popular criticism of Congress suggests, trust in Congress serves as a critical component and determinant of public trust, both because of the formal responsibilities of Congress under the Constitution and because of the breadth and depth of its electoral ties to the complex multiplicity of individuals and groups that make up the American public. This was true in the nineteenth century, and it is even more true today, given the vast expansion in the scope of the federal government. Although the character of the expectations its constitutional position generates has changed with the rise of the modern presidency, Congress’s power over and responsibility for the success of representative government at the national level continue to be so substantial that they render trust in politics and politicians at all levels of government particularly sensitive to judgments of the representativeness, integrity, and effectiveness of its processes and members.

The formal position of Congress in our constitutional order as lawmaker and overseer of the executive branch, the great leverage over public policy it retains, and the public perception of its role and responsibilities make the dynamics of public distrust far more understandable. Whatever the realities of American politics, the public’s predispositions to see Congress as the most powerful branch, to attribute inaction to its penchant for careerism and partisanship, and to judge it more harshly than the president for legislative stalemate become far less anomalous than they first appear (Hibbing and Theiss-Morse, 1995; Durr et al., 1997). Nonetheless, distrust in Congress is only part of the puzzle and cannot be understood in isolation. It is impacted by and related to distrust in political institutions and politicians generally, to distrust in institutions and leaders in other sectors of society, to declining levels of personal trust, and in the end to the changing values and interests of American society (Uslaner, 1993). Indeed, the complex character of these relationships is itself perhaps the most defining feature of the puzzle. The various chapters of this volume thus treat the problem of distrust in Congress as part of a more general problem. As a result, although most of them focus directly on distrust in Congress, they vary greatly in terms of the features of distrust they emphasize and the scope and character of the causal factors they address.

My purpose in this chapter is to provide a context for understanding the thrust, fit, and significance of the work of each of the authors in this volume. To do so both the shared assumptions that unite these authors and the rationales for the different stances they take in analyzing distrust must be understood. I will therefore begin by expanding my sketch of the puzzle so that I can tie these assumptions and rationales to the major issues that constitute the puzzle. Once that is accomplished, the work of the authors can be briefly summarized in a manner that delineates their relationships to one another and identifies their contributions to understanding and alleviating distrust.

Distrust in the 1990s

To unravel the puzzle of public distrust both in government and in Congress, we must deal with several central issues. What are the causes of distrust? How dangerous is the current state of distrust for the future of American democracy? If distrust is sufficiently dangerous to arouse concern, what can be done to alleviate it? Answers to these questions are complicated not only by the complexity of the relationships between causal determinants within the political system and between the political system and the broader society, but also by the variegated character of public trust itself. From the polling data alone we can sense that trust is not a unidimensional entity, but rather a layered one, consisting of different forms or types of trust at different levels of governance. As suggested earlier, belief in the basic legitimacy of the political system, in the representativeness and integrity of governmental decisionmaking units and officials, and in the ability of government to devise and implement policy programs that satisfy citizen demands are all components of public trust. They can and should be seen as different dimensions or levels of trust that exist simultaneously but vary greatly over time, both individually and relative to one another. Thus, the contours of public trust in recent decades need to be broadly identified before causes can be analyzed, dangers assessed, and remedies evaluated.

These contours appear to be quite different from those that led to the breakdown of the political system in the 1850s.* Whereas distrust in that era focused far more on the legitimacy of the purposes and design of the political system than on the integrity of politicians and their responsiveness to the electorate, distrust at present appears to have very different features or characteristics. But it too is far from consistent across the various levels or dimensions of trust.

On the one hand, as I have suggested, trust or confidence at what we may call the governmental level is low. Public cynicism regarding the manner in which government works and the factors that motivate politicians seems almost palpable in its strength and intensity (Hunter and Bowman, 1996; Orren, 1997). Elected officials are widely dismissed as self-serving politicians who are far more concerned with promoting their careers and gaining partisan advantage than with acting responsibly to promote the general welfare (Craig, 1996). Though many believe that public opinion, when united and intense, can check these tendencies, they also recognize that as a practical matter such occasions are rare. As a result, the public views politics as a process, dominated by special interests that trade campaign funds and electoral support for access and influence at the expense of the broader public and the public interest (Hibbing and Theiss-Morse, 1995). Similarly, it views politicians as persons whose honesty and adherence to principle are in most cases corrupted by their career ambitions and the requirements for success in politics (Bowman and Ladd, 1994). There is more confidence in the integrity of non-elected officials, especially the federal bureaucracy, but limited confidence in their effectiveness and efficiency. Government generally, and especially the federal government, is thus not viewed, as it was from the late 1930s through the late 1960s, as a ready and reliable instrument of public purpose, but rather as a flawed mechanism of questionable integrity and effectiveness (Craig, 1996; Blendon et al., 1997).

On the other hand, prevailing attitudes at other levels or dimensions of trust can and do differ significantly from those that prevail with respect to trust in the character of governmental decisionmaking and decisionmakers. Though it is true that the public sees politics as controlled by special interests, politicians as dishonest and unprincipled, and government generally, especially the federal government, as ineffective and wasteful, this is only part of the truth, not the whole truth. Public attitudes are also marked by a number of anomalies or contradictions. Despite the fact that most Americans believe that the processes of representative government are corrupted by money and dominated by special interests, belief in the legitimacy of the political system and emotional attachment to it remain high (Hunter and Bowman, 1996). Thus, belief in and attachment to the constitutional roles of the three branches of the national government remain strong, whatever the character of opinion toward their actual performance or the honesty of the individuals who constitute and lead them (Hibbing and Theiss-Morse, 1995). As a result, though it may be true that the public tends to judge Congress harshly for simply doing its job, a job that necessarily involves conflict and controversy, it remains true that the necessity for and role of a legislature are accepted, not challenged. Indeed, the fact that the Congress invariably scores lower than the president on a number of indicators of trust can be read, in part, as testimony to the strength of public attachment to the principles of representative government implicit in the Constitution. As suggested earlier, these principles lead citizens to take a very pristine view of Congress’s constitutional responsibilities and to judge the Congress more stringently than the president when results are perceived to be inadequate.

Similarly, although the poll data show quite clearly that since the early 1970s most Americans have consistently believed that government cannot be trusted to do “what’s right” all or even most of the time, and that their trust in the people who lead Congress and the White House has decreased, public approval of the job performance of the president and Congress, as well as of the state of the nation and the direction in which it is moving, is quite volatile and has varied widely over the past quarter-century (American National Election Studies, 1996; Gallup, 1998). In short, as the data presented in the Appendix show, trust at the policy level as well as trust at the system level can diverge significantly from trust at the governmental level.

To illustrate the point, in the spring of 1998 (when this chapter was written) both presidential and congressional job performance scores were high, despite the scandal that broke in January 1998 involving President Clinton. Presidential job approval scores in the first four months of 1998 were in the mid to upper 60s. These scores compare well with the upper range of scores attained by other presidents in recent decades, and they are also the highest scores Clinton had attained since entering office in 1993 (Stanley and Niemi, 1995; Washington Post, 1998). Congressional approval scores over time have been consistently and substantially lower than presidential approval scores. But in the first four months of 1998 they climbed into the mid 50s before declining to the high 40s, a height and a range they have attained only rarely in recent decades (Stanley and Niemi, 1995; Washington Post, 1998). General measures of approval of the state of the nation or the direction in which it is headed, which can also be read as indicators of satisfaction with and confidence in the broad course of public policy, reflec...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title

- Copyright

- Contents

- List of Tables and Figures

- Foreword: Trust and Democracy: Causes and Consequences of Mistrust in Government, Senator Bill Bradley

- Acknowledgments

- 1 The Puzzle of Distrust

- 2 Insiders with a Crisis from Outside: Congress and the Public Trust

- 3 Appreciating Congress

- 4 Congress and Public Trust: Is Congress Its Own Worst Enemy?

- 5 How Good People Make Bad Collectives: A Social-Psychological Perspective on Public Attitudes Toward Congress

- 6 Congress, Public Trust, and Education

- 7 Performance and Expectations in American Politics: The Problem of Distrust in Congress

- Epilogue: The Clinton Impeachment Controversy and Public Trust

- Appendix: Trends in Public Trust, 1952-1998

- About the Editor and Contributors

- Index