- 224 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

Green lifestyles and ethical consumption have become increasingly popular strategies in moving towards environmentally-friendly societies and combating global poverty. Where previously environmentalists saw excess consumption as central to the problem, green consumerism now places consumption at the heart of the solution. However, ethical and sustainable consumption are also important forms of central to the creation and maintenance of class distinction. Green Consumption scrutinizes the emergent phenomenon of what this book terms eco-chic: a combination of lifestyle politics, environmentalism, spirituality, beauty and health. Eco-chic connects ethical, sustainable and elite consumption. It is increasingly part of the identity kit of certain sections of society, who seek to combine taste and style with care for personal wellness and the environment. This book deals with eco-chic as a set of activities, an ideological framework and a popular marketing strategy, offering a critical examination of its manifestations in both the global North and South. The diverse case studies presented in this book range from Basque sheep cheese production and Ghanaian Afro-chic hairstyles to Asian tropical spa culture and Dutch fair-trade jewellery initiatives. The authors assess the ways in which eco-chic, with its apparent paradox of consumption and idealism, can make a genuine contribution to solving some of the most pressing problems of our time.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Green Consumption by Bart Barendregt,Rivke Jaffe in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Social Sciences & Sustainable Development. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Part I

From Production to Consumption

–2–

Adversaries into Partners? Brand Coca-Cola and the Politics of Consumer-Citizenship

Robert J. Foster

Eco-Chic: Political Consumerism and the Paradoxes of Corporate Partnerships

In her insightful book Political Virtue and Shopping, political scientist Michelle Micheletti (2003: 14) observes: “Economic globalization and concerns about global justice have. . . shifted the venue of politics to the market sphere and change[d] the orientation of action from pressure group politics and social movement agitation to targeting transnational corporations directly through purchasing choices and less conventional political methods as culture jamming, hactivism, and guerilla media stunts.” Micheletti accordingly cautions us not to dismiss the possibility that individual consumption practices can function as a vehicle for political action and civic virtue. On the contrary, Micheletti (2003: 15) argues: “Political consumerism carves out new arenas for political action by its involvement in the market and the politics of private corporations. . . . It considers individual citizens as main actors in politics by emphasizing the responsibility of each and every citizen for our common well being.”

This chapter considers the possibilities of political consumerism or consumer-citizenship directed against transnational corporations. The question mark in the title indicates my ambivalence about the prospects of consumer-citizenship for effecting progressive change—that is, for changing present conditions of social and economic injustice through boycotts, buycotts, and other methods such as culture jamming that appeal to individuals primarily as consumers, especially consumers of brand-name commodities.1 My intention is neither to contrast so-called real politics to political consumerism nor to oppose citizen and consumer as distinct, irreconcilable identities. Nor is it to expose consumer-citizenship as a corporate conspiracy to co-opt moral conscience and social critique. Such a blunt analysis would fail to recognize the heterogeneous motivations, expressions, and consequences of commodity activism (see Mukherjee and Banet-Weiser 2012). I am sympathetic to Micheletti’s position, and I have previously adopted it with respect to the politics of consumption surrounding soft drinks (Foster 2008a). But I have become less optimistic over the last several years, mainly as a result of observing how corporations such as The Coca-Cola Company (TCCC) have responded to agitation by concerned consumer-citizens.2 I will discuss here some of the reasons for my declining optimism, highlighting in particular the paradoxical character of corporate partnerships made in the name of environmentally responsible consumption.

Selling eco-chic is now a minor part of the business of TCCC. For example, the company’s website celebrates the possibility of “creating value through sustainable fashion” in its account of the Drink2Wear t-shirts launched in 2007.3 These t-shirts, which sold for under $20 at the online Coca-Cola retail store, were made from a blend of recycled plastic bottles and cotton; they featured snappy slogans such as “Rehash Your Trash” meant “to promote recycling and eco-friendly food and clothing.”

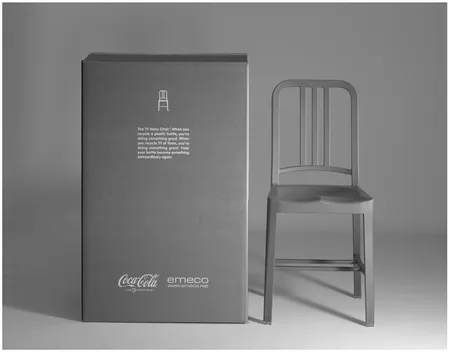

If you are understandably inclined to doubt the fashion credentials of these plastic t-shirts, then perhaps a more upscale example of eco-chic will persuade you to accept the company’s claim. In 2010, TCCC announced the debut of a chair made from 111 recycled plastic bottles blended with glass fiber and offered in several colors (Figure 2.1).

Figure 2.1 Emeco 111 Navy Chair made from 111 recycled plastic Coca-Cola bottles. Image courtesy of Emeco.

The chair was modeled on the classic aluminum Emeco Navy Chair designed in 1944 for the U.S. Navy and manufactured in a way to make it three times harder than steel. Like many other instances of eco-chic, the Emeco 111 Navy Chair at $230 aligns tasteful and stylish consumer choices on the part of affluent shoppers with concern for the environment. This particular instance, however, is notable for its effort to co-brand the product. The chair is not only an Emeco chair, but also a Coca-Cola chair.

TCCC has engaged in other co-branding efforts that qualify as eco-chic. For example, in 2007 the company formed a partnership to produce a line of handbags made from misprinted or discontinued labels of Coca-Cola bottles. Kelli Sogar, then the company’s merchandise manager, worldwide licensing and retail operations, commented: “We have made great strides in reducing our waste output from our bottling plants or label manufacturing facilities, and we are constantly seeking ways to reduce our environmental footprint. This partnership allows us to repurpose materials. Best of all, we are helping to create greater awareness on environmentally and socially responsible consumption.”4

In this instance, fashion sensibility aligns with concern not only for the environment, but also for women struggling against the challenges of poverty. The co-branding links TCCC with Ecoist, a family-owned business that converts waste into raw materials for fashion accessories. Ecoist is committed to “investing in the lives of our workers, their families, and their communities.” For example, the company’s website claims that the Coca-Cola handbags are made by “a certified fair trade women’s cooperative in Peru.”5 Ecoist itself, in turn, partners with Trees for the Future, and plants a tree “in places like Haiti, India and Uganda” for each handbag sold. According to the company’s website: “By definition, an Ecoist is ‘an individual that lives a modern, eco-minded lifestyle.’ We hope to inspire people to become ‘Ecoists’ so we can all live in a healthier, better, and more peaceful planet.”

How does fighting poverty and protecting the environment create value for companies like TCCC? Specifically, how are we to understand the sort of partnership into which TCCC has entered with Ecoist—partnerships with not only companies but also assorted nongovernmental organizations (NGOs) devoted to environmental and social causes in the developing world? What can we learn about eco-chic by asking about the partnership rather than the lifestyle politics implicated in the purchase of the handbags; by highlighting the corporation instead of the consumer, and business strategies instead of cultural trends? That is, what is the political economy of eco-chic as opposed to its psychology or anthropology?

Partnership is one of the key words in the discourse of corporate social responsibility (CSR) that has flourished since 1999. The term indicates a type of global governance that Christina Garsten and Kerstin Jacobsson (2007) call “post-political,” in which consensual and voluntary forms of regulation take the place of involuntary regulation imposed by states on parties with conflicting interests (see Ferguson and Gupta 2002). The ideal of partnership epitomizes the post–UN Global Compact world in which political conflict around corporations is replaced by a set of transcendent moral codes of conduct, a world in which longstanding corporate adversaries—including NGOs and civil society organizations (CSOs)—are turned into allies.6 Win-win solutions replace negotiated compromises and winner-take-all outcomes. As Cairns et al. emphasize in their contribution to this volume, it is precisely this perfect alignment between the interests of business and the greater good of society that eco-chic also promises.

What possibilities do these partnership strategies open up and shut down for the practice of political consumerism and consumer-citizenship? More generally, what are the prospects for economic democracy within the rubric of postpolitical governance? In addressing these questions, I will demonstrate how current understandings of brand value in the business world compel corporations to engage with consumers, including consumer-citizens. I will argue that brands—especially global brands associated with fast-moving consumer goods—can therefore provide a platform for civic action on a transnational scale. I draw on my work on one particular brand—Coca-Cola—to illustrate how corporations have developed new techniques for stabilizing this platform and for managing the actors who appear on it.

The shift in the venue of politics into the market sphere identified by Micheletti prompts a rethinking of what resistance to corporate power might look like (see Mukherjee and Banet-Weiser 2012). This rethinking in turn demands acknowledging a corollary shift in the venue of business into the sphere of NGOs and CSOs (as well as the continuation of corporate efforts to lobby public officials at all levels of government). I thus do not dismiss consumer-citizenship or political consumerism as inevitably oxymoronic, especially when the terms are understood broadly to include practices such as shareholder activism and coordinated public actions in the manner, for example, of civil rights protests against segregated buses and lunch counters. I suggest, however, that the corporate partnerships characteristic of postpolitical governance are themselves often oxymoronic inasmuch as they purportedly reconcile manifestly incompatible goals, such as protecting the environment and selling more bottled water. These alliances present difficult, new challenges to consumer-citizens wishing to harness the potential of markets for progressive social reform let alone radical change.

Political Consumerism in a Time of Brandization

Political consumerism has a long history, as the etymology of the word boycott attests.7 There is, however, a new condition of possibility for political consumerism—for using market-based actions to achieve goals ordinarily imagined as civic matters. It is a condition associated with the increasing importance to corporations of intangible assets, that is, the increasing share of a corporation’s market capitalization that is accounted for by intangible assets. By intangible assets, I mean, specifically, brands.

We are all familiar with how companies today routinely reduce costs by outsourcing commodity production to distant sites where cheap labor is available. The flipside of this global movement is perhaps less familiar. It is what Hugh Willmott (2010) gives the deliberately inelegant name of brandization: the monetization of brand value.

Willmott provocatively argues that in the current era of “financialization” corporations invest in branding not to extend the market or to increase market share or even to charge a higher premium price. Rather, the goal is to leverage the value of the brand for shareholders, for example, through royalties derived from its use by other corporations. Brands, therefore, become a source of revenue by attracting investors persuaded that brand-owning companies will grow at a faster pace than those companies without brands.8 Investment increases share price, and thus market capitalization “against which cheaper lines of credit and the debt-financing of expansion or acquisition activity can be secured” (Willmott 2010: 524). Hence, the dividends and capital gains that accrue for investors as a result of increased share price represent surplus value created and extracted, in Willmott’s words, “beyond the point of production.” Given that CEOs have strong and multiple incentives to boost share price (incentives that include personal compensation packages tied to performance; see Bashkow forthcoming), brandization is an appealing managerial strategy.

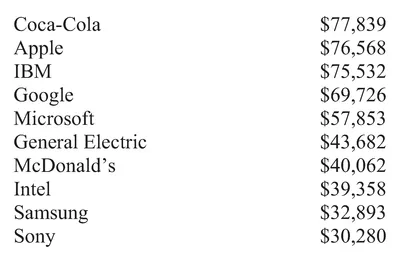

Brandization, however, entails more than corporate ownership of strong brands; it requires the translation of brand strength into brand value by means of the market device of brand valuation—a device that puts an agreed upon monetary price on a brand (see Foster 2013 for a more extensive discussion). Without brand valuation, it is difficult to say how much of a corporation’s market capitalization can be attributed to its brands (and to the work of the marketing department). A number of brand consultancy firms—most prominently, Interbrand—provide valuation services. The number-one global brand in terms of monetary price in the 2012 annual report released by Interbrand in conjunction with BusinessWeek magazine was Coca-Cola, valued at more than $77.8 billion and up 8 percent in value from the year before (Figure 2.2).

Interbrand 2012 Top Ten Global Brands by Value (in USD millions)

Figure 2.2 Interbrand’s 2012 Top Ten Global Brands. Source: http://www.interbrand.com/en/best-global-brands/2012/Best-Global-Brands-2012-Brand-View .aspx, accessed February 2, 2013.

Brand valuation acknowledges, if only implicitly, that brands are contingent outcomes of relationships—ongoing, changing, not always predictable relationships. In this sense, a brand is like a reputation, an interactive social construction. And brand management and reputation management are closely connected corporate concerns. As Interbrand strategist Tom Zara (2009: 3) puts it: “Brand has become even more important in separating the winners from the losers in a marketplace where corporate reputations have been battered by scandals and bruised by recession.” Furthermore, damage can now be done to brands more easily by agents outside the corporation—hacktivists and culture jammers empowered by an array of social media technologies. This observation is particularly apt in cases where the brand and the corporate entity are identical: McDonald’s, Disney, and Coca-Cola—all companies in which brand value is estimated to comprise more than 50 percent of market capitalization (unlike, say, the case of Procter and Gamble or Pfizer, companies that own multiple brands with different identities).

Brand and reputation are thus similar economic objects with respect to the possibilities of political consumerism. They are both found at the limits of managerial control inasmuch as they involve a company’s external relationships. These external relationships encompass a broad array of stakeholders. Interbrand identifies six fields of stakeholders—employees, customers, suppliers, the communities in which companies operate, the governments that influence operations, and the planet that all companies rely on for existence. The challenge of bringing all of these relationships under managerial control is daunting, to say the least!

Managing Relationships: Value Cocreation and Risk

There are two relationships in particular to which the idea of brandization calls attention: the crucial relationship between a brand owner and brand users (or consumers) and the relationship between brand owners and concerned citizens who are not necessarily consumers—more or less enduring publics that emerge around specific issues or events (see Foster 2008a). Both of these relationships are inherently unstable. Brandization requires turning both unruly consumers and unruly publics into willing partners.

There is far more at stake in the relationship between brand owners and consumers than what has been understood as customer loyalty. Corporations today readily concede that brands are often the creations of consumers as much as the products of brand managers, designers, and marketers. Consumers are regarded as “co-creators” (Prahalad and Ramaswamy 2004) or “prosumers” (Ritzer and Jurgenson 2010); they perform consumption work (see Miller 1988). That is, the strength or equity of a brand depends on the extent to which consumers use the brand as a medium or instrument of their own “affectively significant relationships” (Arvidsson 2009: 17), as a resource for the sort of self-realization that Marx associated with unalienated labor (see Miller 1987).

I have come to understand this use of brands as a form of consumption work that brand owners attempt not only to manage, but also to exploit as a source of surplus value (see Banet-Weiser and Lapsansky 2008; Foster 2008b, 2011). That is, brand owners derive rent from the purchases of consumers who pay to use a brand that, through a consumer’s own particular postpurchase use, has become entangled in his or her life projects. The challenge confronting brand managers, then, is to make sure that the brand stays aligned with the consumer’s autonomous interest in cocreating it. This challenge involves what Adam Arvidsson calls a risky “logistics of meaning and affect” (2009: 18), which if mishandled results in the consumer’s withdrawal of his or her consumption work, thereby reducing the brand’s social currency (its coolness) and thus its strength or equity.

Interbrand makes it clear that similar risk is distributed through all of a company’s external relationships with stakeholders. For example, with regard to business-to-business relationships: “purchasers understand that they can be held accountable by the public for their suppliers’ actions. So pressure that begins externally—in the net’s 24-hour court of public opinion and among a press ready to feed the beast—winds up being passed along every link in the [supply] chain” (Zara 2009: 3).

In short, the rhetoric of Interbrand is a rhetoric that produces the risk and uncertainty that the firm’s services promise to manage. Indeed, it is not implausible to argue that brand valuation is itself a new form of risk and uncertainty with which companies must deal. Michael Power’...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Contents

- List of Figures

- Contributors

- Foreword

- PART I: FROM PRODUCTION TO CONSUMPTION

- PART II: SPATIALITIES AND TEMPORALITIES

- PART III: BODIES AND BEAUTY

- Notes

- Bibliography

- Index