eBook - ePub

Japanese Colonialism In Taiwan

Land Tenure, Development, And Dependency, 1895-1945

- 256 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

Exploring the dynamics of development and dependency, this book traces the experience of Taiwan under Japanese colonial rule. Chih-ming Ka shows how, unlike in other sugar-producing colonies, Taiwan was able to sustain its indigenous family farms and small-scale rice millers, who not only survived but thrived in competition with Japanese sugar capital. Focusing on Taiwan's success, the author reassesses theories of capitalist transformation of colonial agriculture and reconceptualizes the relationship between colonial and indigenous socioeconomic and political forces. Considering the influence of sugar on the evolution of family farms and the contradictory relationship between sugar and rice production, he explores the interplay of class forces to explain the unique experience of colonial Taiwan.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Japanese Colonialism In Taiwan by Chih-ming Ka in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Politics & International Relations & Asian Politics. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

Land Tenure, Class Relations, and the State in Precolonial Taiwan (1683–1895)

Taiwan's unique land tenure system, derived from the land reclamation activities in this frontier island, was characterized by the powerful usufruct rights of perpetual tenants.1 Unlike the mainland, which had its predominant gentry landlords, in Taiwan's remote settler society the lack of effective authority by the central government permitted the rise of a patent-holder class that organized land reclamation. Once land was opened, however, this class faded away. Because the patent holders were far removed from the land after land reclamation (most of them became city dwellers), the growth of a perpetual tenant class (tien-hu) steadily eroded the land rights of the patent holders. The usufruct rights of the perpetual tenants finally developed into a quasi-ownership tenure (the hsiao-tsu tenure) immune from the supervision and control of patent-holder landlords. The hsiao-tsu tenure of perpetual tenants eventually developed into modern landownership under Japanese rule.

Heritage of Colonial Rule

Prior to Dutch rule (1624-1661), Taiwan was inhabited by several aboriginal peoples, tribes whose deer hunting and swidden cultivation made up their major economic activities. As early as the fourteenth century, Chinese and Japanese visited the island as merchants, fishermen, and deer hunters. Chinese pirates also used Taiwan and the P'eng-hu (Pescadores) islands as bases to harass the mainland coast during the second half of the sixteenth century. Not until the Dutch East India Company (which ruled Taiwan for the Dutch) encouraged Chinese migration and promoted agriculture in the middle of the seventeenth century was there any significant commodity cultivation in Taiwan (Campbell 1903: 9-10). The Dutch recruited Chinese peasants from the mainland; supplied them with seeds, farm implements, and oxen to open the virgin land around the port, Fort Zeelandia; helped them construct irrigation systems; and provided protection against aboriginal attacks (Chang-hua County Gazetteer 1830: 162; Campbell 1903: 117). The Chinese peasants were obligated to pay the Dutch not only rent in kind but taxes in cash. In order to acquire the money for production and taxes, the Chinese sold agricultural products, basically rice and sugar, as well as deerskin to the company (Nakamura 1954: 57-64; Campbell 1903: 155, 186-187). By imposing heavy taxes in the form of customs on its Chinese and Japanese commercial competitors, the company was able to dominate trade in Taiwan. Although the original purpose of the occupation of Taiwan was mainly to facilitate Dutch trade in East Asia, the Dutch in Taiwan drew lavish profits not only from the triangular trade with China and Japan but from various taxes, particularly those on agriculture (including rent) and deer hunting. In 1653 the revenue from croplands was one-third of trade profits, sufficient to cover the annual expenditures of the company in Taiwan (Nakamura 1954: 61).

The Chinese peasants were organized into reclamation groups led by local headmen who were in turn supervised by the Dutch. Each peasant (including their headmen) received a piece of land after reclamation according to his contribution in capital and labor and paid rent to the Dutch for its use. There was apparently no differentiation between landlord and tenant classes among Chinese peasants. The selling and leasing of land was restricted for better control of the Chinese tenants or was considered unnecessary by tenants because of the abundance of available land (Okuda 1954: 44-45, 47).

All land was vested in the name of the monarch. The Chinese peasants worked the crown land as tenant farmers (Chang-hua County Gazetteer 1830:162; TSI: 66; Campbell 1903: 36). The Chinese peasants were not free to move or to choose their residences (Campbell 1903: 396-397, 476). Although labor services on the demesne were not imposed, the subordination of Chinese peasants to the Dutch East Indies Company was signified primarily by their obligation to pay a poll tax and other taxes for fishing, hunting, and butchering pigs, in addition to rent, as on the European continent after the thirteenth century (Bloch 1961: 255-279; Hilton 1983: 20; Nakamura 1954: 51; Campbell 1903: 64, 186-187, and 254). A number of Japanese scholars thus have suggested that the European manorial system was transplanted to Taiwan in the Dutch period (Okuda 1954: 45-46; Higashi 1955: 8).

However, the Dutch did not foster a self-sufficient manorial economy. Rice production was encouraged to provide needed food. But sugarcane production grew most rapidly. Sugar became the prime export commodity of Taiwan and made Taiwan the biggest sugar exporter of the Dutch colonies in the 1650s (Nakamura 1954: 61-62). The motivation for the colonial presence in Taiwan was profit making. The increasingly important role of the Dutch in the international trade of East Asia contributed greatly to commodity production in Taiwan. The manorial system introduced from Europe, far from acting as a barrier to the promotion of commodity production and circulation in Taiwan, stimulated its development.

After defeating the Dutch, the family of Cheng Ch'eng-kung (Koxinga), the Ming dynasty loyalist who fled from the mainland, took over their crown lands and ruled Taiwan from 1662 to 1683. Under Cheng rule the arbitrary taxes imposed on tenants were increased. For military purposes, the Chengs emphasized subsistence grain production. Hence, even with large-scale land openings, sugarcane production was greatly reduced, from 17,000 chia to 10,000 chía (1 chia = 0.97 hectare) (Nakamura 1954: 61; Ts'ao 1954: 83). This contrasts sharply with the Dutch company's strategy, its primary concern being cash-crop production for trade.

During the Cheng family reign, officials (most of them military: Cheng had 338 military officials but only fifty-six civil officials) and local strongmen were encouraged to enclose land as their own private lands (szu-t'ien), with the exception of the crown lands (Hsu W. H. 1980a: 22; Yang 1662: 189-190; Ts'ao 1954: 75). This meant acquiring territory outside of the crown land, from aboriginal peoples. The method used was military colonization. Settlers, the majority retired soldiers, were organized by experienced officers and became tenants on the szu-t'ien of the latter. The standing army was also involved in military colonization in order to achieve self-sufficiency in food. The standing army opened up ying-p'an-t'ien (land of the armed forces), which was tax exempt, while lords on szu-t'ien paid the Cheng family land taxes, about one fourth that of the crown land (see Table 1.1). Like the Cheng family, military lords, who paid part of their income to the Cheng family as tribute, also claimed the right to tax almost every form of production in their territory (Yang 1662:190). In addition, the lords had to supply soldiers (recruited from their tenants) to the Cheng family in wartime (Chiang 1704: 234, 260, 267, 375). Through this kind tenure system, settler society in Taiwan was reshaped for warfare. The Chengs' military organization was identified with or permeated deeply into Taiwan's settler society (Chiang 1704: 206; Shih Lang in T'ai-wan County Gazetteer 1807: 418).2

TABLE 1.1 Tax Rates on Croplands According to Date of Registration and Locations (in shih of unhulled rice per chia)a

| Dates of Registration | ||||

| Kind of Farmland | 1662-1683 | 1684-1729 (southwest )b | 1729-1744 (central and north)c | 1744-1885 (central and north)d |

| Private Land: | ||||

| Paddy Land | ||||

| Upper | 3.60 | 8.8 | 1.7583 | 2.740 |

| Middle | 3.12 | 7.4 | 1.7583 | 2.080 |

| Lower | 2.04 | 5.5 | 1.7583 | 1.758 |

| Dry Land | ||||

| Upper | 2.24 | 5.0 | 1.7166 | 2.080 |

| Middle | 1.62 | 4.0 | 1.7166 | 1.758 |

| Lower | 1.08 | 2.4 | 1.7166 | 1.716 |

| Crown Land (1624-1661):e | ||||

| Paddy Land | ||||

| Upper | 18.0 | |||

| Middle | 15.6 | |||

| Lower | 10.2 | |||

| Dry Land | ||||

| Upper | 10.2 | |||

| Middle | 8.1 | |||

| Lower | 5.4 | |||

a 1shih of unhulled rice = 0.5 shih milled rice = 41.41 kg.

b The croplands of southwestern Taiwan were mostly former crown lands and lords' lands, which were distributed to tenant cultivators during the Ch'ing period (1683-1895).

c The sudden drop in tax rates in 1729-1744 was a response to the islandwide peasant revolt led by Chu I-kuei in 1721-1722 and subsequent small-scale revolts influenced by Chu in the 1720s.

d The croplands in central and northern Taiwan were the newly opened lands during the Ch'ing period.

e The tax rates on crown lands in the Cheng period (1662-1683) were the same as those in the Dutch period (1624-1661).

Sources: Chi Ch'i-kuang in Gazetteer of Taiwan Prefecture, Fukien 1871:164-165; TSI: 110-122.

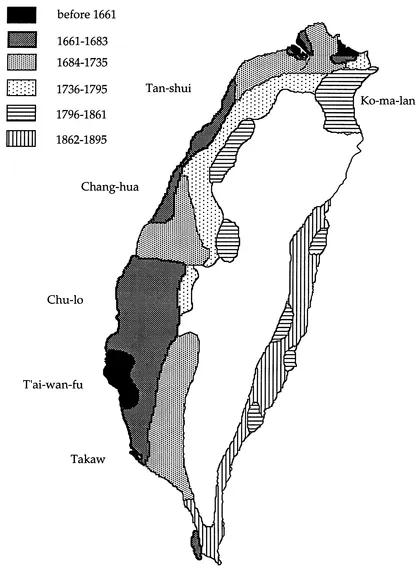

MAP 1.1 Settlement in the Ch'ing Dynasty

Source: Ts'ao 1954: 81; Chang Ch'i-yün 1962: B43; Shepherdl993:175.

Source: Ts'ao 1954: 81; Chang Ch'i-yün 1962: B43; Shepherdl993:175.

The Land Reclamation Organization: The Rise and Decline of the Patent-holder/Perpetual-tenant (K'en-hu/Tien-hu) System

In contrast to the lord-owned land system that prevailed during Cheng rule, lords' prerogatives in Taiwan were eliminated under Ch'ing rule (1684-1895). Even though the Ch'ing emperor claimed ownership of all land within his empire, he nevertheless granted tenurial rights to his subjects as long as they paid taxes. In Taiwan former tenant farmers of the Cheng family and its lords became owners of the land they had possessed during the Cheng period and were free to transmit landownership to their sons and to sell and purchase land. In cases where peasants became tenants to landlords, they were bound by a commercial contract rather than a bond of personal obligation to their masters; labor obligations and military service no long existed. The government poll-tax was also greatly reduced and abolished altogether in 1747 (Lien 1918:153).

In addition to the transformation of landownership, there was another important discontinuity from Dutch and Cheng rule. The transfer of confiscated land from the Cheng family and its lords to their tenant farmers led to relatively even distribution of land among peasant smallholdings at the beginning of Ch'ing rule. As evi...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title

- Dedication

- Copyright

- Contents

- List of Tables and Illustrations

- List of Photographs

- Foreword

- Acknowledgments

- INTRODUCTION

- CHAPTER 1 LAND TENURE, CLASS RELATIONS, AND THE STATE IN PRECOLONIAL TAIWAN (1683-1895)

- CHAPTER 2 THE COLONIAL STATE, FOREIGN CAPITAL, AND THE ARTICULATION OF INDIGENOUS AGRICULTURE

- CHAPTER 3 FAMILY FARMS AND THE FORMATION OF SURPLUS EXTRACTION MECHANISMS BY SUGAR CAPITAL

- CHAPTER 4 THE CONTRADICTORY RELATIONSHIP BETWEEN RICE AND SUGAR

- CONCLUSION

- Appendix: Prices, Income, and Land Productivity in Rice, Cane and Sugar Production, 1910-1938

- Bibliography

- Conversion of Weights and Measures

- Glossary

- About the Book and Author

- Index