![]()

Part I

Concepts and Terminology

![]()

1 Schenker’s Conception of Musical Structure

An Overview

Introduction

I have always liked to begin my courses on Schenkerian analysis with an overview of his conception of musical structure. There is a danger, of course, in overloading the newcomer with too much information; despite this, I see definite advantages to this approach. First, it has been my experience that many students, even those with some background in the area, have developed strange notions about Schenker and his work, and this overview can help to dispel some of the misconceptions. Second, it provides a glimpse into where this study will take us. And third, it provides a review of basic concepts and terminology for those with some background.

We will begin by examining what I take to be three basic premises on which Schenker’s mature theories are built. First is his observation that melodic motion at deeper levels progresses by step. Second is his understanding that some tones and intervals, such as the dissonant seventh, require resolution. And third is the distinction Schenker draws between chord and harmonic step (Stufe), which may incorporate a succession of many chords. We will then examine in detail Bach’s well-known Prelude in C Major from the Well-Tempered Clavier, Book I. We will begin by examining its harmony and metric organization and then proceed to a consideration of its voice-leading structure. This will give us an opportunity to examine Schenker’s concept of structural levels as well as the specific techniques of prolongation involved. Finally, we will consider Schenker’s notion of motivic repetition as related to that of structural levels. The chapter will end with a review of concepts and terminology.

Three Basic Premises

Melodic Motion by Step

Schenker’s theoretical publications span almost thirty years, from 1906 until 1935, the year of his death. Sometime during this period, most likely early on, he observed that melodic progressions beyond note-to-note connections have a tendency to progress by step. Today this observation seems quite apparent, but historically it has great significance as Schenker’s ideas on structural levels began to develop. We will begin by examining four relatively short examples, provided in Example 1.1, from this perspective.

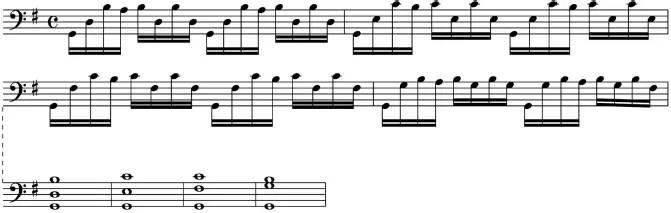

a) The first example is the opening four measures of the Prelude from Bach’s Cello Suite in G Major, where each half measure consists of an arpeggiated chord with the top note decorated by its lower neighbor. The reduction below the score shows the underlying progression of two voices over a tonic pedal. The inner voice progresses by step from D3 to G3, while the top voice progresses from B3 to its upper neighbor C4 and back. The controlling harmony is the G major chord, and the progression of the top part prolongs the third of the chord by its upper neighbor.

EXAMPLE 1.1a Bach, Cello Suite I, Prelude, 1–4

b) Our second example is the opening of the sarabanda movement from Bach’s Violin Partita in D Minor. Here the note-to-note progression of the melody involves motion back and forth between two melodic strands, a top voice and an inner voice, sometimes progressing by leap and at other times filling in the gap by step. This phenomenon is commonly referred to as compound melody. (Our first example is also an example of compound melody, consisting of two parts above a stationary bass.) The melodic leaps in the first three measures are between these two strands, but individually each progresses by step. As shown by the representation of the voice leading below the music, the top voice descends by step from F5 to B♭4. The first two steps in this progression, which fall on successive downbeats, are clear. The entrance of D5 in the third measure is delayed until the last eighth note, and the C5 of measure 4 is displaced by D5 on the downbeat. Nevertheless, it is this C5, which becomes the dissonant seventh in relation to the D7 chord, V7 of iv, that leads to B♭4 in the next measure. Once you look and listen beyond note-to-note associations, all voices in this example progress by step, including the bass. The E♭4 on the downbeat of measure 4 belongs to an inner line, only temporarily delaying the connection between B♭3 and A3 in the bass within the larger descent of a fifth from D4 to G3.

EXAMPLE 1.1b Bach, Violin Partita II, Sarabanda, 1–5

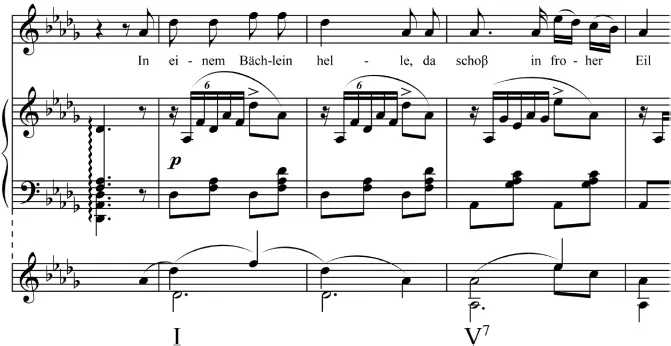

c) Our third example is taken from Schubert’s famous song, “Die Forelle”. Here the surface progression involves arpeggiation between inner and outer strands until the step connection between E♭5 (outer voice) and A♭4 (inner voice) at the end of the excerpt. The initial arpeggiation occurs within a single harmony (tonic), as occurred in the opening example, and then the leap from A♭4 to E♭5 and the reverse filling in of that interval occur over the dominant.

This creates a step progression between the top notes of the arpeggiations, F5 to E♭5, harmonized by I to V7, as shown in the reduction below the example.

EXAMPLE 1.1c Schubert, “Die Forelle”, 6–10

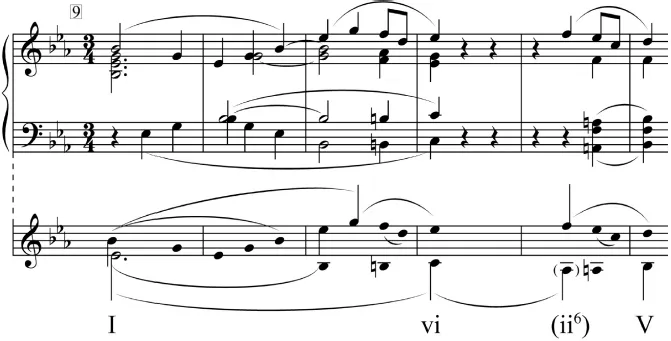

d) Our final example is taken from the third movement of Beethoven’s Piano Sonata in E♭, Op. 7. Here the melody once again opens with an arpeggiation of the tonic triad, which reaches up to G5 in measure 11, at which point the line descends a third with the middle member of the third extended to its lower third. This idea is then repeated a step lower, creating the step progression G5 (measure 11)-F5 (measure 13). This is shown clearly in the interpretation of the voice leading of this passage provided below the music. (Here the notation does not indicate relative duration but the hierarchy of events.) The function of the C minor chord (vi) is shown to be part of a descending arpeggiation in the bass from I to ii6, where the bass note A♭ has been omitted and is thus shown in parentheses. It is common practice in Schenkerian graphs to show notes implied by context but not stated explicitly in this manner.

EXAMPLE 1.1d Beethoven, Piano Sonata Op. 7 (III), 9–14

These examples are concerned with connections in relatively close proximity, but as Schenker’s notion of structural levels began to take shape, he quite naturally became concerned with connections at more remote levels. Regarding step progressions, he observed that at deeper levels these invariably descend, and at the deepest level they descend to closure. The concept of closure, which for Schenker means both melodic and harmonic closure—the simultaneous arrival at scale degree 1 and tonic harmony—is central to his concept of tonality. Closure can occur at many levels—for example, at the end of a theme or musical period, or over the course of an entire piece, in which case we are talking about closure of the fundamental line and fundamental structure. Once again, we are touching on the idea that music operates simultaneously at different structural levels. But we are getting ahead of ourselves; we will get to this shortly.

Resolution of the Dissonant Seventh

The second basic premise that I like to stress early on in introducing Schenker’s ideas is his recognition—hardly a new one for his time!—that certain notes of the scale have specific tendencies—for example, and to resolve to and This general notion is reflected in the title of one of his publications, a series of pamphlets with the name Tonwille, which literally means “will of the tone(s)”. I like to demonstrate with a few examples involving resolution of the dissonant seventh, since it is extremely important not only to be aware of the normal treatment of this dissonance but also especially to be aware when encountering those special circumstances where the seventh is not treated as expected. First, let’s observe the resolution of the dissonant seventh under “normal” circumstances.

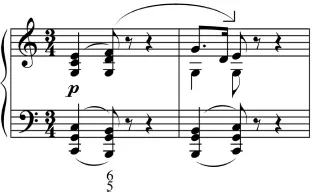

a) The meaning of the first example, the opening two measures from the second movement of Beethoven’s Piano Sonata, Op. 7, is perfectly clear. Here resolution of the F4 on the second beat of measure 1, the dissonant seventh of the dominant, is delayed until the second beat of measure 2. Similar to the initial example in the previous section, the opening of the prelude movement of the first Cello Suite by Bach (Example 1.1a), the third of the tonic harmony is prolonged by its upper neighbor.

EXAMPLE 1.2a Beethoven, Piano Sonata Op. 7 (II), 1–2

b) Our second example is the opening measures from the third movement of Mozart’s Piano Sonata, K. 570. Here we have another example of a compound melody, where the lower strand proceeds from D5 on the downbe...