- 360 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

In the completely revised second edition of this highly praised book, Susumu Yabuki, one of Japan's leading China experts, and Stephen M. Harner, A Shanghai-based investment banker, present a comprehensive and accessible analysis of China's political economy.The authors provide dozens of easy-to-grasp and up-to-date graphs, charts, tables, and maps to illustrate the reality of China, as they explain and comment on political, economic, financial and trade trends.Placing issues in historical perspective, and with a view to trends into the twenty-first century, the authors survey the realities of China's area and population, agriculture, energy needs, pollution, industrial structure, township and village enterprises, state-owned enterprise reform, unemployment, economic regions, foreign investment, state finances, fiscal and monetary policy, China's financial institutions, foreign financial institutions in China, stock markets, international finance, balance of payments and exchange rate policy, corporate finance, the role of Shanghai, government institution reform, foreign trade, the roles of Hong Kong and Taiwan, U.S.-China relations, and Japan-China relations.Useful as an introduction to China's economics, finance, and politics for students, and as a desktop reference volume for corporations, organizations, and individuals considering doing business in China, this unique study fills a genuine gap in the literature.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access China's New Political Economy by Susumu Yabuki,Stephen M Harner in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Politics & International Relations & Asian Politics. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Part One

Toward a Basic Understanding of the Chinese Economy

1

A Huge Country

An Amalgamation of “Small Countries”

China’s Area and Population in Global Perspective

When Mao Zedong was young he admitted to dreaming of founding the "Republic of Hunan." After the founding of the People's Republic of China, Mao repeatedly revived this youthful dream. In the essay "On the Ten Great Relationships" (1956) he spoke of the proper relationship between the provinces and Central as being one of limited local autonomy. During the Great Leap Forward (1958-1960) the dream of a communal system was realized in the people's communes. During the Cultural Revolution period (1966-1976) he spoke of establishing a Shanghai commune.

The origin of Mao's dream is the notion of "small nations with few people" in a "titular ruler republic."

In the end, a titular ruler republic is best. Both the queen of England and the emperor of Japan are titular rulers in titular ruler republics. In the end, it is best for Central to be a titular ruler, responsible only for the setting of broad political policy. The broad political policy should be formulated based on opinions collected from the localities. Central should make policy as though it were a processing factory using raw materials from the regions. Central can only set policy after actively eliciting the opinions from the provincial and county levels. In other words, Central should manage "form" only, and not "substance." (Mao Zedong, Long Live Mao Zedong Thought, p. 638)

What would happen if no one died? If today, Confucius were still living, the earth could not support humanity. We should applaud the behavior of Zhuang Zi who joyfully beat a tray when his wife died. We should hold celebrations at funerals and toast the victory of the dialectic. Isn't this a celebration of the destruction of old things? (Mao Zedong, "Talks on Some Philosophical Questions," in Long Live Mao Zedong Thought, p. 559)

Anyone contemplating the hugeness of China becomes a philosopher.

Another United Nations: “The Chinese Confederation of States”

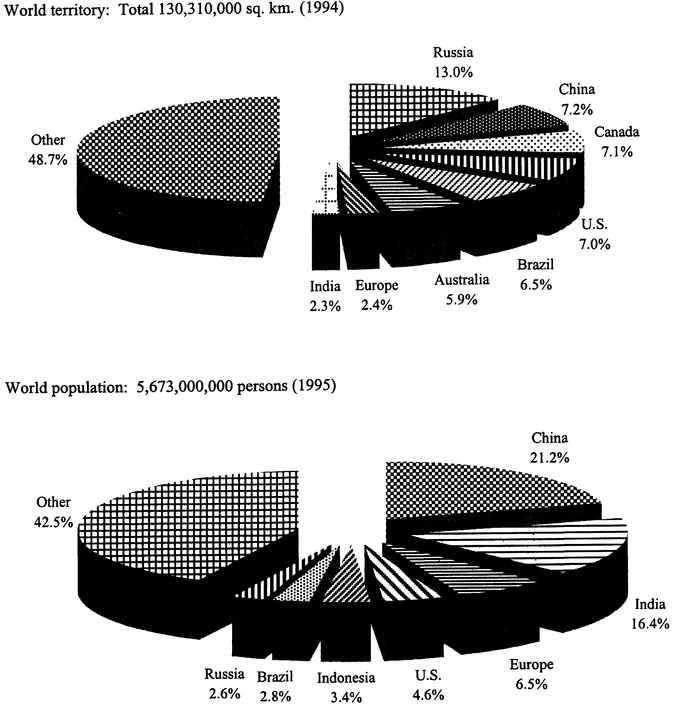

Figure 1.1 presents China's land area and population shares of the world's totals. With land area covering more than 7 percent of the globe, China is second after Russia, followed by Canada, the United States, and Brazil. What about population? Of the world's 5,673 million people, more than 21 percent are Chinese. In other words, one-fifth of the people on the planet are Chinese. However, China has implemented a rigid, one-child-per-family restriction, and it is forecast that by the middle of the twenty-first century the population of India will surpass that of China. With 21 percent of the world's people occupying just 7 percent of total land area, China's population density is three times the world average.

Comparing Shanghai and Singapore, we see that Shanghai's land area is ten times that of Singapore, whereas its population is nearly five times greater. Comparing the industrial province in China's northeast, Liaoning, to South Korea, we see that it is about 50 percent larger in land area yet has roughly 10 percent fewer people. Guangdong province is China's southern gateway. It has a land area some 60 percent of that of the Philippines, whereas the population is almost equal (roughly 70 million). The formerly combined administrative areas of Chongqing municipality and Sichuan province (separated in 1997 as Chongqing became a municipality directly subordinate to Beijing) had a population of more than 100 million, nearly equal to that of Japan (whereas Sichuan's land area was some 50 percent greater than that of Japan). The directly administered municipality of Chongqing has a population of some 30 million, so the population of former Sichuan is reduced by this number.

We may allow ourselves to imagine that within a single country, China, we have entities like Singapore, South Korea, the Philippines, and Japan. Were we to continue, we could draw parallels for more than thirty "countries." Mao Zedong at one time compared China to "another United Nations." There is, indeed, this aspect of China.

China has more than 54 minority peoples, and even the Han race differs significantly in language and eating habits from north to south and east to west. It is impractical to apply common perceptions of the modern nation-state when speaking about this huge a country.

China’s Provinces—Like Separate Countries

Let us take this idea further and compare the land areas of China's province-level administrative units with those of other Asian countries. With the largest area of all China's provinces, the Xinjiang Uigur Autonomous Region is smaller than Indonesia but larger than Iran. The Tibet and Inner Mongolia Autonomous Regions are smaller than Mongolia but larger than Pakistan. Qinghai province is between Turkey and Myanmar, Sichuan province is between Afghanistan and Yemen, Heilongjiang and Gansu provinces are between Turkmenistan and Uzbekistan. The area of Yunnan province is slightly larger than Japan's total area, Guangxi Autonomous Region is roughly the size of Laos. Among the smaller regions, Ningxia Hui Autonomous Region is larger than Butan. Beijing, Tianjin, and Shanghai municipalities are about the same size as Kuwait, Qatar, and Brunei, respectively.

FIGURE 1.1 China's Share of World Territory and Population

Source: The World Bank, World Development Indicators, 1997.

Source: The World Bank, World Development Indicators, 1997.

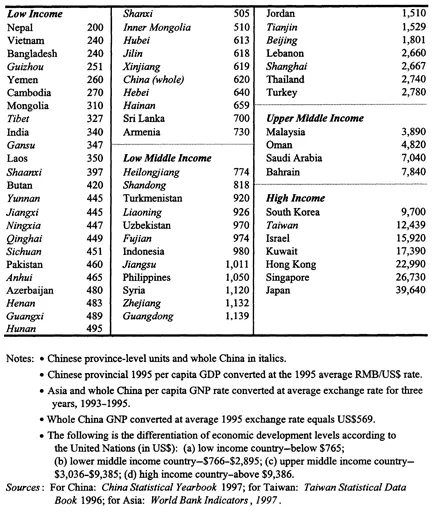

TABLE 1.1 Comparison of Per Capita GNP of Asian Countries and China's Province-Level Administrative Units

What if we compare the populations of China's province-level administrative units with those of Asian countries (data for China from China Statistical Yearbook 1966; data for other countries from United Nations publications)? Starting from the smallest, Tibet (2.38 million) is close to Mongolia (2.46 million), Qinghai province (4.74 million) and the Ningxia Hui Autonomous Region (5.09 million) are close to Laos. Hainan province and Tianjin municipality are close to Azerbaijan. Beijing (12 million) and Shanghai (14 million) municipalities are at the same level as Yemen. The Xinjiang Autonomous Region is a little smaller than Kazakhstan. Inner Mongolia, Gansu, Jilin, Shanxi, Fujian, Guizhou, Shaanxi, Heilongjiang, Yunnan, Jiangxi, Liaoning, and Zhejiang provinces have populations between 20 and 40 million, falling between North Korea (24 million) and South Korea (45 million). The Guangxi Autonomous Region (45 million) is on par with Myanmar; Hubei (57 million) and Anhui (60 million) provinces with Iran (68 million); and Hunan, Hebei, and Guangdong provinces with the Philippines (70 million). Jiangsu (70 million), Shandong (87 million), and Henan (91 million) provinces are close to Vietnam (74 million).

Table 1.1 is an attempt to present a comparison in terms ot per capita gross national product (GNP). China as a whole, with per capita income of US$620 (U.S. dollars are used throughout this book unless otherwise specified), is ranked as a "low income country" (below US$765). Twenty province-level administrative units could be assigned to the "low income country" category. The lowest is Guizhou province at US$251, followed by Tibet at $327. At the same time, however, ten province-level units have reached the "low middle income country" ($776-$2,895) level: Heilongjiang, Shandong, Fujian, Jiangsu, Guangdong, Zhejiang, Liaoning, Tianjin, Beijing, and Shanghai. At the top is Shanghai with $2,667 (this reached $3,000 in 1997). Of course, Hong Kong, now returned to the motherland, is in the "high income country" category. In short, China's regions have attained income levels ranging from among the highest to among the lowest by world standards. Thus, China is an amalgam of "small countries" constituting a whole, distinct world.

—Yabuki

2

Population Pressure

The Challenge of 1.6 Billion People in 2030

The Chinese Population Pyramid

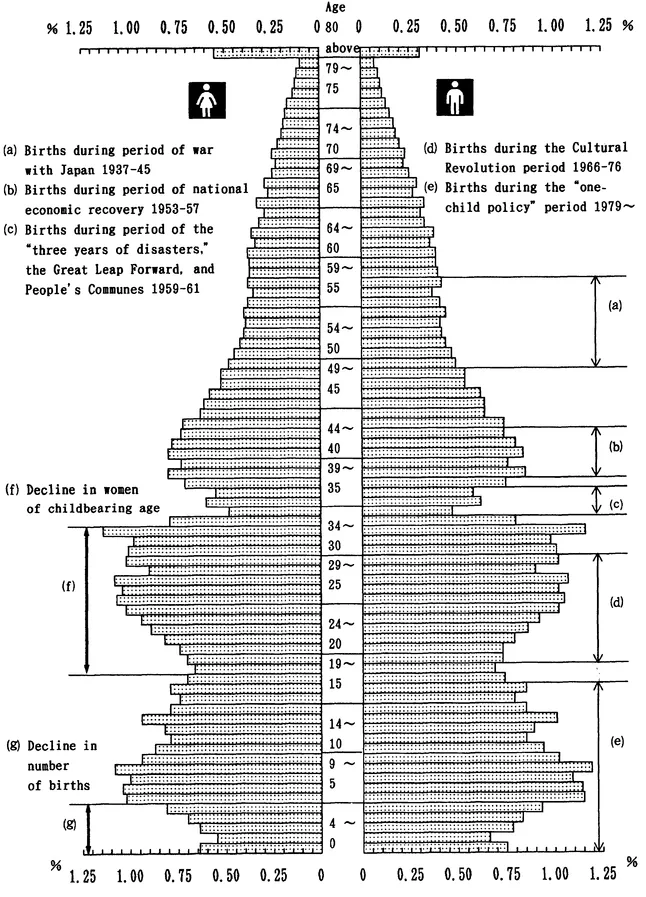

Let us look at China's population pyramid as of October 1, 1995 (Figure 2.1).

Generation Born During the Anti-Japanese War

There was previously a clear compression during this war period. What appears now is a only a pattern of virtually no population growth.

Period of Economic Recovery

This was the postwar baby boom. Population grew rapidly as the economy of the newly established state enjoyed rapid recovery under political stability after the long war.

Period of Natural Disasters

This is the period of the so-called three consecutive years of natural disasters (actually manmade disasters) following the Great Leap Forward. The reality of widespread famine-related deaths in the weakest—newborns— is visible. A spokesman for the State Statistics Bureau stated on September 13, 1984, that more than 10 million people died from starvation due to manmade factors and natural disasters during the Great Leap Forward. Knowledgeable estimates place the death toll at roughly 20 million.

Cultural Revolution Period

From the period of economic adjustment that began in 1962 through the first half of the Cultural Revolution, in the context of growing political

FIGURE 2.1 Population Pyramid from the October 1, 1995, Census (1 percent sampling)

Source: China Statistical Yearbook 1996, p.72.

Source: China Statistical Yearbook 1996, p.72.

disorder, the birthrate rose substantially (the second baby boom). A birth control system was instituted during the second half of the Cultural Revolution, and the effects of state-mandated birth control began to surface.

The One-Child Policy

In the first half of the Deng Xiaoping era, starting in 1978, a fairly coercive one-child-per-family policy was implemented. There followed a striking drop in the population's growth rate. By the second half of the 1980s opposition to the population control policy compelled the state to grant a policy exception, in villages only, permitting families to have two children if the firstborn was a girl. Also there was an increase in "black children" (hei haizi)—children not registered under the family registration (Hukou) system and therefore unrecognized—which further shook the population control regime. However, during the 1990s, birthrates have rapidly declined. The drop in births in 1994 was particularly remarkable. That reflected the firm grounding of the one-child policy together with a drop in the childbearing population of eighteen-to thirty-two-year-old women (State Statistics Bureau, China Population Yearbook 1995, p. 347).

Population Trends Since 1949

Figure 2.2 presents in graphic form the increase in both rural and urban populations. Starting at 540 million in 1949, China's population reached 600 million in 1954, 700 million in 1964, 800 million in 1969, 900 million in 1974, and broke 1 billion in 1981. In 1988 it surpassed 1.1 billion, and in 1995 1.2 billion. The 1.2-billion level had been a population control policy target for the year 2000; a new target of 1.3 billion has been substituted. At the end of 1996 the population stood at 1,223,890,000.

If we try to create a rough model of the PRC's population growth, we find that during the 1950s the average annual increase was 20 million (a total of 200 million for the decade), during the 1960s 25 million (total 250 million), during the 1970s 20 million (total 200 millio...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title

- Copyright

- Dedication

- Contents

- List of Tables and Illustrations

- Preface to the English Language Edition

- Preface to the Japanese Edition

- List of Acronyms

- Introduction: Six Realities and Unrealities About the Chinese Economy

- Part 1 Toward a Basic Understanding of the Chinese Economy

- Part 2 Some Domestic Economic Problems

- Part 3 State Finances, Financial Institutions and Markets, and Government Institution Reform

- Part 4 Foreign Trade, Foreign Capital, and External Economic Relations

- Appendix A: A Chronology of China's Liberalization and Reform, 1978-1998

- Appendix B: Key Indications for China's Economy, 1978-1997

- Selected References

- Index