- 454 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Interpretative Archaeology

About this book

This fascinating volume integrates recent developments in anthropological and sociological theory with a series of detailed studies of prehistoric material culture. The authors explore the manner in which semiotic, hermeneutic, Marxist, and post-structuralist approaches radically alter our understanding of the past, and provide a series of innovative studies of key areas of interest to archaeologists and anthropologists.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

Part I

Space, Architecture and the Body

Chapter 1

Frameworks for an Archaeology of the Body

Tim Yates

Correct me if you want to

but there is nothing more useless than an organ.

When you have given man a body without organs

You will have delivered him from all his automatisms

And given him back his true freedom.

but there is nothing more useless than an organ.

When you have given man a body without organs

You will have delivered him from all his automatisms

And given him back his true freedom.

Antonin Artaud

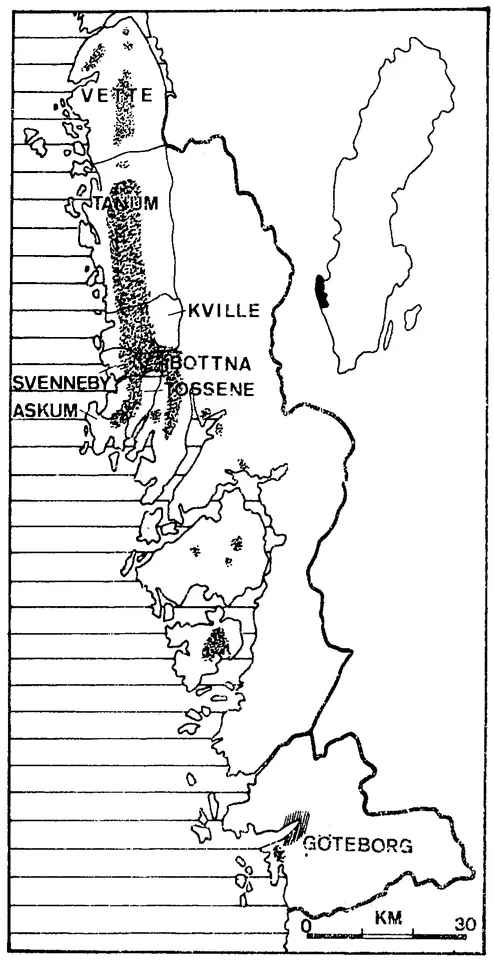

One of the richest prehistoric resources available to archaeology are the rock carvings of the county of Goteborgs och Bohuslän, situated on the west coast of Sweden and extending from the city of Göteborg to the Norwegian border. Although the normal types of archaeological data for this period and area are present, our principal resource is monumental art, rather than metalwork or graves. Scattered across the county are over 2000 individual 'sites', composed of at least 2500 individual panels. Precise figures depend largely on the ways in which sites and panels are defined. They consist of a range of designs incised and pecked into the surface of exposed bedrock, mainly granite, which accounts for some 30 per cent of the total area. Most of these designs fall into six major generic categories: cup-marks (simple, round depressions, usually between 4 and 8 cm in diameter), ships, human and animal figures, foot marks and circular designs. With the cup-marks not much can be done, and I will not discuss them further here. Of the remaining motifs, which are in some way representational and might be described as 'figure' carvings, ships form the single largest category, and are found at over twice as many panels as any of the other motif classes, while the footmarks are the least common, and have accordingly a much smaller territorial distribution.

Representations of the human figure make up the second most common representational motif found in the rock carvings, and the county has the highest proportion and absolute number of human figures of all areas with prehistoric art in northern Europe. I shall confine myself to the rock carvings of the area north of the town of Munkedal, where most of the carvings are found (Figure 1.1). Although there are significant concentrations of carvings in Göteborg, and on the islands of Tjörn and Örust, anthropomorphic figures are very rare. The material from the northern part of the county offers the best scope for exploring how sexuality was represented, therefore, in prehistory. Within this area I shall also limit myself to those areas of the county for which modern documentation exists - the hundreds of Kville (Fredsjö, Nordbladh and Rosvall 1971, 1975, 1981) and Vette (Yates n.d.) - and will exclude, therefore, the equally rich areas of Tanum, Tossene and Askum, for which no detailed documentation has taken place in recent years.

The patterning in the art with which I shall be concerned can be described as morphological - one which focuses on the variation manifested in the range of different human figures, and with the connections between these figures and other designs. My concern is with the representation of the body, therefore, and - with the exception of animal figures - I will not discuss the morphology of the other major classes of design. The aim is to draw out the ways in which the body and its sexual identity are represented, not to account for the art as a whole.

There have been few systematic attempts to study and interpret the morphology of the human figures. The two major studies of the rock carvings of Bohuslän - Nordbladh (1980) and Bertilsson (1987) - are both preoccupied with the place of the carvings in the landscape and the co-occurrence of the different classes of motif on the panels. Morphological details as defined here are discussed, but not examined in great detail. Nordbladh (1989) has also discussed the occurrence of armed figures in the rock carvings of Kville hundred. Papers have appeared regularly in the journal Adoranten,dealing with different aspects of the art, but have lacked any systematic sampling of the data. The only detailed and systematic approach based on a consideration of the

Figure 1.1Location map of Götebocgs och Bohuslän, showing places. mentioned in the text. The stippled area represents the main areas with carvings.

variation within human figures is found in Mats Malmer's 'chorological' study (Malmer 1981).

Malmer bases his study of the material from Bohuslün on the depictions of the carvings published by the Dane Lauritz Baltzer, updated by reference to surveys published after the completion of the initial study in 1972. The latter are used to form a 'control corpus' (sic). Although the scale is impressive, the study in its final form makes depressing reading, since, where interpretations are offered, they appear either totally ignorant of or immune to any of the theoretical debates of the preceding twenty years, indeed of the very environment in which it has been written. If the material was revised between the completion of the manuscript and publication to take account of new data, the conclusions and methodology have not. Here is diffusion alive and kicking in the 1980s:

...every archaeological type was first produced by one person living in a certain place at a certain time; thence the new idea spread to his immediate neighbourhood, and from there in ever-increasing circles, until it eventually reached the limits of our diffusion map. (Malmer 1981: 1)

No account is taken of the local processes behind the art, and although lip-service is paid to the importance of regional differences in meaning, the underlying approach is founded on the assumption that the phenomenon 'Nordic prehistoric art' (the unity of which is not so much examined as assumed) expresses the same fundamental ideas:

in the central area of West Denmark, most interest is shown in abstract and symbolic designs: circular designs, hands and feet. Immediately to the east of West Denmark, mainly in Bohuslän, but also in Østfold, West Sweden and Scania, there is a pronounced interest in scenes....This may be explained by postulating that cultic ceremonies performed in West Denmark and well-known in these areas, were here portrayed in stone as there was less opportunity to practice them in real life.(Malmer 1981: 104; emphasis added)

Although Malmer works hard to bring to light the differences between areas in terms of the types of design found within them, the study is unable to explain or even address these differences. Indeed, the conclusions offered end up denying the variation the book spends over 100 pages establishing. This is to be explained by the fact that no attempt has been made to theorize what variation in the motifs might mean: without a framework which will account for these differences, the data produced are redundant, and the conclusions drawn from them colourless and trite.

The study of human figures illustrates this point clearly. Malmer boasts that the classificatory scheme is capable of producing anything between 144 and 522 possible types, but no attempt is made to interpret what the different types that exist mean. The scheme produces information with a built-in redundancy. Partly this is because the author has adopted a scale of analysis which blocks off any access to such meaning - we are left with statements about the universal depiction of items of wealth and status (p. 106) of the most startling banality.

Contrary to both Malmer's and Burenhult's (1980) claims, the way forward for rock art analysis is notto address issues of chronology but to theorize the art - a theorization which must extend way beyond the stale discussions of terminology - and study its appearance and meaning in local and regional terms. We should start from the local and regional, and from that point investigatewhether there are any similarities. It is our rubric, as archaeologists, to question, not to assume. Malmer notes that rock art is generally not portable, and thus can only be indigenous, but his study fails to pursue this point and its contribution to the understanding of prehistoric rock art in the north is at the best limited.

In order to avoid producing a superfluous and redundant amount of information, I have chosen a simpler classificatory scheme than Malmer's, This scheme recognizes the following divisions. For the human figures:

- Unarmed figures - figures without either sheathed sword or weapon held in the hand.

- Unarmed figure with sheathed sword but without other weapon.

- Armed figure with sheathed sword and at least one other weapon.

- Armed figure without sheathed sword but with at least one other weapon.

These classes are cross-referenced to the presence of the following characteristics: erect phallus, with or without testicles; exaggerated or otherwise emphasized calf muscles; exaggerated or emphasized hands and /or fingers; figures with horned helmets; figures with long hair. Note was also made of the connections between different motifs in the art, such as human figures onboard ship designs or joined to disc motifs, and of the proximity of cup-marks to the different areas of the body.

Regarding chronology, I have opted to treat the rock carvings as a whole, since I remain unconvinced by any attempts to date the rock carvings through reference to their occurrence on other, dateable media (metalwork), in dateable contexts (burials), or particularly on supposed typological/stylistic features (Marstrander 1962; Glob 1969; Almgren 1963; Burenhult 1980; Malmer 1981). Scandinavian archaeologists, with the exception of those working in Goteborg, seem to have faith, bordering on the theological, both in the existing schemes and in the potential to refine them and produce schemes of ever greater sophistication. Meaning is thrown out of the window. Malmer's study shows that it is necessary to suspend consideration of chronology in order to approach meaning behind the motifs. Of course, there will be those who regard such an approach as dangerous, and who will continue to typologize and seriate until kingdom come. All we need note here is that in the last century such individuals have failed bothto construct a rigorous chronology and to say anything of interest about the carvings. They have had their chance: it is time to experiment with other approaches.

The distribution of the different typological features on the human figures found in the study areas is shown in Tables 1.1 and Figure 1.2. From these graphs and tables, we can make the following observations:

- Armed phallic figures - figures with scabbards or with scabbards and weapon - are twice as common as corresponding non-phallic figures. The lowest values of non-phallic figures with scabbards is 10 per cent (Bottna), the highest 25.5 per cent (Vette). The corresponding highest and lowest values for phallic figures are 45.2 per cent (Bottna) and 89.1 per cent (Svenneby).

- Non-phallic figures are four times as likely to occur unarmed as phallic figures. The highest value of unarmed non-phallic figures is 81.7 per cent (Bottna), the lowest 63.6 per cent (Vette). The corresponding highest and lowest values for phallic figures are 41.9 per cent (Bottna) and 4.3 per cent (Svenneby).

- Although the number of figures in the sample with weapons is small, making it difficult to draw conclusions about the types of weapon carried by phallic and non-phallic figures, it is clear that the latter rarely carry drawn swords, just as they are much less common to carry sheathed swords than phallic figures. Similarly, they are only seldom depicted with spears. They are equally likely to carry axes, and perhaps marginally more likely to carry bows than phallic figures. The only figure with a lur in the sample (on the panel at Hogdal 223) is non-phallic. Phallic figures show a stronger relationship to helmets than non-phallic figures.

- Exaggerated hands occur with equal frequency among phallic and non-phallic figures.

- Exaggerated calf muscles reveal a stronger association with phallic than non-phallic figures.

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Series Page

- Title

- Copyright

- Dedication

- Contents

- Preface

- Introduction: Interpretation and a Poetics of the Past

- Part I: Space, Architecture and the Body

- Part II: Symbolism, Politics and Power: Alternative Discourses

- Part III: Archaeology and Capitalism: The Institution and Society

- Notes on the Contributors

- Index

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Interpretative Archaeology by Christopher Tilley in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Social Sciences & Anthropology. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.