![]()

1

Introduction: ‘Urbanism as a Way of Life’

This book is not a history of German urbanization, as it is usually conceived (Lee 1978; Bosl 1983; Kenny and Kertzer 1983; Matzerath 1981; idem 1985; Reulecke 1985; de Vries 1984). Nor is it a ‘city history’ (Lenger 1986; Benevolo 1993). Rather, its aim is to explore the German experience of ‘urbanism as a way of life’, to borrow Louis Wirth’s memorable phrase (Wirth 1938). Writing in the late 1930s, Wirth developed three criteria which he thought analytically useful for the study of urbanism.

Document 1.1 Urbanism as a Characteristic Mode of Life

Urbanism as a characteristic mode of life may be approached empirically from three interrelated perspectives: (1) as a physical structure comprising a population base, a technology, and an ecological order; (2) as a system of social organization involving a characteristic social structure, a series of social institutions, and a typical pattern of social relationships; and (3) as a set of attitudes and ideas, and a constellation of personalities engaging in typical forms of collective behavior and subject to characteristic mechanisms of social control.

Source: Louis Wirth, ‘Urbanism as a way of life’, American Journal of Sociology, Vol. 44 (1938), 18–19.

By the third decade of the twentieth century over two-thirds of Germans lived in towns and cities, and those who did not, found themselves inexorably sucked into an ever-widening urban vortex. For Wirth noted an intensification of urban life as a social and cultural phenomenon from the end of the nineteenth century to the beginning of the twentieth century that inaugurated a ‘modern age’ of the city lasting, perhaps, until the 1960s (Wirth 1938: 2, 5, 7; Hall 1998; Gee et al. 1999). Taking the urban experience as a paradigm for modernity (Harvey 1985; idem 1989; Katznelson 1991; Lees 1991; Hays 1993), this book sets out to explore the wider social history of its everyday reception in the German context.

If, as I argue, the urban experience is a paradigm for German society, can the German urban experience serve as a paradigm forthe European experience? I believe it can. The urban population of Europe had grown sixfold between 1800 and 1910, with the period of greatest concentration occurring roughly between 1900 and 1913, before tailing off into the early 1920s. The process was most marked in north-western and central Europe, with the rest of Europe only ‘catching up’ from the 1950s (Lampard 1973: 7; Bairoch 1988: 217). On the eve of the First World War, just over 43 per cent of all Europeans (including those living in the British Isles) were living in a town or city. An urban map of Europe would show Britain as the most heavily urbanized country: by 1936, 79 per cent of its population lived in towns and cities; closely followed by the small nations of the Netherlands and Belgium; by Germany with an urban population of 67 per cent; by Italy and then France with 51.2 per cent (Denby 1938: 21–9; Hohenberg and Lees 1985: 215–29; Pounds 1990: 443–6). To the north, south and east of this band (excluding the USSR), the levels of urbanization dropped off dramatically to around 33 per cent and less.

A similar urban geography of a mainly urbanized west and rural east existed in Germany (Bairoch 1977: 217–19; Lichtenberger 1984: 6–10). The most heavily urbanized areas were also the most industrially developed, with sophisticated commercial economies. They were to be found west of the river Elbe. By contrast, to the east of the Elbe in East Prussia, the few urban centres of importance, apart from Berlin, such as Breslau or Königsberg, remained embedded in largely agrarian landscapes (Pollock 1940: 205–337; Bessel 1978: 199–218). Horst Matzerath has shown that by 1910 more than 50 per cent of the population of the industrialized western provinces of Prussia was urbanized, compared with just a third in the eastern provinces (Matzerath 1985: 88–93). Germany, from its geographically centred position in Europe, straddled the urban/rural axis and as such, displayed fully the varied and often contradictory experiences of European urbanization.

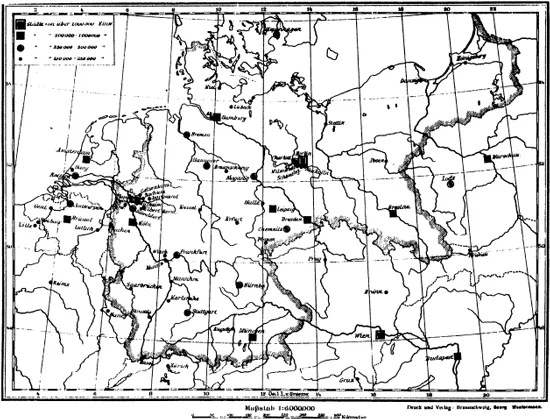

From the 1890s, cities and towns become larger, a growth that continued into the 1920s and even into the 1930s in some parts of Europe. By 1910 there were at least 150 large cities with populations over 100,000 (Pounds 1990: 443), the numerical point defining a ‘big city’, with more than half of these in north-west and central Europe (see Chapter 2). Their number grew over the next two decades. In fact, at the turn of the century, there were 96 big cities in north-west and central Europe. The metropolises – or world cities – with populations over I million, however, numbered only seven at this date, with a further eight ‘big cities’ of between a half and I million (Lawton 1989: 4). At the beginning of the twentieth century in an area of continental Europe designated by the Germans as ‘Mitteleuropa’, there were only two cities that met this criterion for metropolis.

Document 1.2 Metropolis and ‘Big City’ in ‘Mitteleuropa’, c.1917

[See illustration opposite]

Source: Emil Stutzer, Die Deutschen Großstädte, Einst und Jetzt (Berlin, Braunschweig and Hamburg, 1917), front map.

Published at the height of the First World War, Stutzer portrayed a central region of continental Europe dominated by the urban axis of Berlin–Vienna. The national metropoles of Warsaw, Budapest, Amsterdam and Brussels, in the geopolitical terms of his urban map, have been relegated to ‘regional’ capitals, acquiring a similar rank to Hamburg, Breslau, Leipzig, Dresden or Munich. Because Vienna, like Budapest, was a metropolis that had reached its ‘high noon’ before the war (Schorske 1980; Lukacs 1988), whereas Berlin was the acknowledged newcomer, Stutzer’s map also underscores Berlin’s paradigmatic position as the centre of a European urban modernity (Hall 1998: 239–43). For Thomas Mann, writing more than a decade later at a point of crisis, this shift in Europe’s civic gravity brought with it a heavy and necessary burden of responsibility (Kaes et al. 1994: 150–9).

The terms modernity and modernism are often employed interchangeably, as evidenced in the writings of those cultural critics engaged in recent debates over modernity and postmodernity (Turner 1990; Boyne and Rattansi 1990; Docherty 1993). Historians of early twentieth-century Germany, and notably those discussing the urban context during the Weimar period, also tend to use the terms interchangeably, adding modernization to the list (Feldman 1986; Peukert 1987; Lees 1991; Buse 1993: 521; Hall 1998: 937). This can be confusing to the student of urban Germany. In this section, therefore, I will try to define these terms more closely as they are understood in this book.

The German philosopher Jürgen Habermas locates the onset of our modern period in Europe in the second half of the nineteenth century (Habermas 1993: 98–9), reaching its climax around 1930. Its distinguishing feature was its rupturing of time and spatial consciousness, and its anticipation of the future. In order to distinguish it from previous ‘modern’ epochs, this period of innovation and change is referred to as ‘classical modernity’, denoting its authenticity and formative role in what was to become familiar to the late twentieth century (Habermas 1993: 99; Harvey 1989: 23). Because of the close alignment to the ‘cultural explosion’ of the Weimar years, the foreclosure of ‘classical modernity’ coincides with the epochal rupture represented by the Nazi takeover of power in 1933 (Peukert 1991: 3–18, 275–81). Yet some of the documents included in the present volume might suggest that there is a good case to extend the periodization to include the decade after 1930 (Hein 1992: 10, 14; Nerdinger 1993: 9–23; Gassert 1997: 151–8).

Although Habermas was concerned more with the shift in artistic engagement with the ‘modern’, the cultural break from mid-century was only made possible because of the rapid and thoroughgoing transformations taking place in European society. The primary change was that of industrialization and urbanization, which appeared to go hand-in-hand, heralding a process of societal modernization. The European big city became emblematic in this process (Bosl 1983: 7–16; Lichtenberger 1987: 4). And increasingly, contemporaries turned to Germany where they believed the process was paradigmatic, though not unique. It was here that modernization in its guise of technological advancement was most visible and actively promoted (Hietala 1987). The Dresden City Exhibition in 1903, for instance, celebrated the urban sphere as a site of progress in the sense not only of machine technology, but also of technical processes of bureaucratic organization, data intelligence, and so on (Wuttke 1904); it is understood in this way in the present volume. As well as being the product of cultural processes, technological modernization also influenced cultural change. It is interesting to note that the relationship between culture and technology was the keynote subject of the first conference of German sociologists in Frankfurt am Main in 1910, and it appeared with some regularity thereafter in the pages of their learned journals (Sombart 1911; Schulze-Gävernitz 1930).

Perhaps the most important outcome of the dialectics of culture and technological modernization of ‘classical modernity’ was the altered consciousness of time, which shifted from a static experience to a ‘transitory’, ‘elusive’, ‘ephemeral’ and ‘dynamic’ one, whose very celebration, according to Habermas, also ‘discloses a longing for an undefiled, immaculate and stable present’, but one which was also always on the point of vanishing into the future (Habermas 1993: 99; Frisby 1985: 4, 141; Kern 1983: 31, 81–104). That is to say, the quintessence of ‘classical modernity’ lay in the reception of its own crisis-ridden ambiguity (Peukert 1988: 133–44). ‘Modernity’ is thus understood as a consciousness that was spatially rooted in the city (Frisby 1985: 71), and that, as Andrew Lees has shown, worked itself out in a vehement discursive battle between supporters and opponents of the urban experience (Lees 1985).

Through his writings at the turn of the century, Georg Simmel, increasingly recognized as Germany’s first great cultural sociologist of modernity (Sennett 1969: 8–10; Frisby 1985: 70; Weinstein and Weinstein 1990: 75–7), subjected the experience of this shift in consciousness to sociological interrogation in his study of the inner life of the modern city (Doc. 2.12). Simmel’s approach to the modernity of the city was developed in numerous writings by his former student, the cultural critic Siegfried Kracauer, during the 1920s (Levin 1995: 1–30). Kracauer’s work deals with the perceived impermanence and impersonal nature of the urban experience. Consonant with contemporary thinking, his early work portrays a city socially constituted by multitudes of transitory and fleeting liaisons that intersected randomly within the spatial confines of the ‘lonely city’ (Kracauer 1995: 42–3, 129; Frisby 1985: 105, 111–17, 147ff.; Mumford 1938: 266). By the later 1920s, Kracauer’s most incisive essay on the modern experience, The Mass Ornament, suggested a more controlled environment linked to the invisible unifying force of production and markets.

Document 1.3 The Mass Ornament

The ornament, detached from its bearers, must be understood rationally. It consists of lines and circles like those found in textbooks on Euclidean geometry, and also incorporates the elementary components of physics, such as waves and spirals. Both the proliferations of organic forms and the emanations of spiritual life remain excluded. […]

The structure of the mass ornament reflects that of the entire contemporary situation. Since the principle of the capitalist production process does not arise purely out of nature, it must destroy the natural organisms that it regards either as means or as resistance. Community and personality perish when what is demanded is calculability; it is only as a tiny piece of the mass that the individual can clamber up charts and service machines without any friction. A system oblivious to differences in form leads on its own to the blurring of national characteristics and to the production of worker masses that can be employed equally well at any point on the globe. – Like the mass ornament, the capitalist production process is an end in itself.

Source: Siegfried Kracauer, The Mass Ornament. Weimar essays, translated, edited, and with an introduction by Thomas Y. Levin (Cambridge, Mass., and London, 1995), 77–8.

Simmel and Kracauer were not only dispassionate observers chronicling and dissecting change, they were themselves also grappling with the transformed conditions of the big city. And in doing so, they textualized their own experiences of urban modernity, giving it an aesthetic form. For the purposes of this book, I implicitly allude to this ‘aesthetic modernity’ as ‘modernism’, referring to the particular style of the cultural artefact (i.e. as written text, architecture, and in works of art and film). Many of the sources in this book are modernist in this sense: from the sometimes dissonant images of the expressionist artists, depicting what Kracauer in 1918 termed the ‘unbound arbitrary individualism’ of mass society, to the cool and totalizing New Objectivity from the mid-1920s that corralled these earlier wild energies (Gay 1969: 125–8). These forms not only stylized modernity, they filtered it too (Smart 1990; Hughes 1980). Thus, like sociological texts, statistical compilations, and official reports, these representations were both articulations and constitutive of the urban experience.

As we have noted, urban modernity was an experiential and existential phenomenon, but one which was not haphazard, not least because of the role of institutions in attempting to shape lives into what we might call an architectural edifice of collective cultural experience. Indeed, in order to combat the putative chaos inherent in the transitory nature of the urban experience, enlightenment science sought to organize everyday life into a cogent ‘whole’ (Foucault 1972: 178–95; Hein 1992: 13), according to the principles of what Habermas terms ‘cultural rationalization’.

Document 1.4 The Project of Modernity

The idea of modernity is intimately tied to the development of European art, but what I call ‘the project of modernity’ comes into focus only when we dispense with the usual concentration upon art. Let me start a different analysis by recalling an idea from Max Weber. He characterized cultural modernity as the separation of the substantive reason expressed in religion and metaphysics into three autonomous spheres. They are: science, morality and art. These came to be differentiated because the unified world-views of religion and metaphysics fell apart. Since the eighteenth century, the problems inherited from these older world-views could be arranged so as to fall under specific aspects of validity: truth, normative rightness, authenticity and beauty. They could then be handled as questions of knowledge, or of justice and morality, or of taste. Scientific discourse, theories of morality, jurisprudence, and the production and criticism of art could in turn be institutionalized. Each domain of culture could be made to correspond to cultural professions in which problems could be dealt with as the concern of special experts. This professionalized treatment of the cultural tradition brings to the fore the intrinsic structures of each of the three dimensions of culture. There appear the structures of cognitive-instrumental, of moral-practical and of aesthetic-expressive rationality, each of these under the control of specialists who seem more adept at being logical in these particular ways than other people are. […]

Source: Jürgen Habermas, ‘Modernity: An incomplete project’, in New German Critique, 22 (Winter 1981), 3–15, reprinted in Thomas Docherty (ed.), Postmodernism: A reader (New York, London, Toronto, Sydney, Tokyo and Singapore, 1993), 103.

This ‘cultural rationalization’ was predicated on pathologizing what were perceived as the negative experiences of urban modernity (Kaes 1998: 184). For the period of ‘classical modernity’ was one when the potential for disorder appeared at its greatest, and the means to control that disorder were in their infancy. The transformation from intimate to mass society since the 1890s, the political upheavals during and after the war, the economic anarchy of the postwar years, all solidified into a paradigm of urban chaos (Leinert 1925: 241ff.). Clearly, in the modern city old structures and hierarchies that had once governed society appeared to dissolve, precipitating a climate that was at once exhilarating but full of uncertainty.

Th...