- 472 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

In this highly acclaimed work first published in 1974, Glen H. Elder Jr. presents the first longitudinal study of a Depression cohort. He follows 167 individuals born in 1920?1921 from their elementary school days in Oakland, California, through the 1960s. Using a combined historical, social, and psychological approach, Elder assesses the influence of the economic crisis on the life course of his subjects over two generations. The twenty-fifth anniversary edition of this classic study includes a new chapter on the war years entitled, ?Beyond Children of the Great Depression.?

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Children Of The Great Depression by Glen H Elder in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & World History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

III The Adult Years

The Depression affected people in two different ways. The great majority reacted by thinking money is the most important thing in the world. Get yours. And get it for your children. Nothing else matters.

And there is a small number of people who felt the whole system was lousy. You have to change it. The kids come along and they want to change it, too. But they don’t seem to know what to put in its place.

A woman reformist from an old Alabamian family. In Studs Terkel, Hard Times.

The “Depression experience” has become a familiar theme in folk accounts of adult behavior. Countless Americans who were born before 1929 are convinced, in retrospect, that experiences in the Depression have had an enduring impact either on their lives or on the lives of persons in their age group. And their children, now of college age or older, share this causal view when they assume that a childhood of scarcity accounts for outmoded parental conduct and priorities.

In their simplicity and exaggerated generality, characterizations of the Depression’s continuing imprint ignore the extraordinary diversity of life situations in this historical period, as well as the differing resources with which people encountered hardships. The Depression was not the “worst of times” for all parents and children of the 30s, judging from our evidence, although few were in a position to regard it as the “best of times.” As in any severe crisis, conditions in the 30s are likely to have produced extremes and even contradictory outcomes. In this respect we have assumed that economic hardships and related experiences had the most adverse effect on life patterns and adult personality among the offspring of working-class families.

Our objective in the next three chapters is to trace the effects of economic deprivation and class origin, through related experiences and adaptations, to life patterns and psychological health in adulthood. Life patterns are defined by the timing of major social transitions—the completion of formal education, entry into the labor force, marriage, and parenthood; by occupational status, attained in part through education, and worklife experience; and by social priorities among family, work, leisure, and community activities. Events in the life course have different meaning or implications for the careers of each sex. In the historical context of the Oakland cohort, men were expected to shape their life course through personal accomplishments in education and worklife, while marriage was the primary option and most fateful commitment for women. Since most of the Oakland girls eventually married and achieved adult status through the accomplishments of their husbands, important historical features of their life course are displayed in the lives of the Oakland men—the impact of World War II, change in the occupational structure. For this reason, we shall begin our analysis with the men, follow with the women, and then bring both sexes together in an assessment of their psychological health.

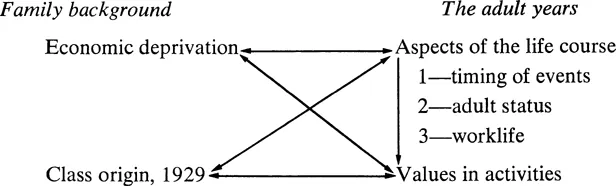

At a general level we shall employ a common analytic strategy in following the Oakland boys and girls into adult life. The diagram shown here outlines three sets of relationships: family background, as indexed by economic deprivation and class origin, to aspects of the life course; family background to values; and family background to values through aspects of the life course. In order to simplify the presentation, we have not specified adolescent adaptations to family hardship and their hypothetical status as linkages between economic deprivation and adult outcomes. For boys these adaptations include early work experience, vocational thinking, and ambition; for girls, domestic experience and interests.

The analysis is organized around three basic tasks: a review of the life course from late adolescence to middle age; an assessment of the impact of family hardship on aspects of the life course; and specification of conditions under which adult values are linked to economic deprivation. There are two objectives in the overview: to describe the Oakland cohort in its historical context and to compare the age group with other cohorts. The long-term impact of economic conditions in the 30s depends in large part on the particular cohort’s life stage at the time. In this respect we need to keep in mind the Oakland adolescents’ entry into adult roles, and especially their point of departure from high school, 1938-39. By this date unemployment had declined appreciably in the Oakland area, and economic activity had surged above the 1929 level. Having passed through the most severe phase of economic privation, young members of deprived families had reason to be relatively optimistic about their future prospects. The nation was only two years away from official entry into World War II, an event which effectively closed the Depression decade and directly influenced the lives of men in the sample. By any standard, life opportunities were more favorable for the Oakland adolescents than for young Americans who came of age five or ten years earlier.

The second task focuses on the determinants of aspects of the life course. In the adult lives of the Oakland men, we shall give special attention to the process of status attainment, to the effect of economic deprivation relative to the influence of class origin, and to factors which link family background to occupational status. Did occupational fortunes generally favor men who did not experience family hardship in the Depression? If so, how can we account for this outcome? Were worklife disabilities related to deprivation or to barriers in the educational route to rewarding occupations? In the case of the Oakland women, we shall investigate two consequential events in their life course and their relation to a background of family hardship: when they married and the kind of men they married. The timing of marriage structures social options and the scheduling of subsequent events (parenthood, employment), while a married woman’s career is dependent on her husband’s occupational achievements.

The analysis to this point will have established a context in which to pose and evaluate questions on the relation between adult values and economic hardships in the Depression. Is there any basis for assuming that the Depression experience of adults makes a difference in their priorities or choices? Much evidence suggests that values are rooted more in the contemporary life situations of adults than in their childhood environments. Accordingly we must take these situations into account as we trace out the long-term effect of family deprivation on things that matter most to the Oakland adults. Under what conditions are specific adult values related to family deprivation in the 30s?

Much of his ambition, drive, and energy comes from the Depression….

Son of a wealthy businessman

Son of a wealthy businessman

I mean, there’s a conditioning here by the Depression. I’m what I call a security cat. I don’t dare switch. ‘Cause I got too much whiskers on it, seniority.

Garbage worker

Garbage worker

7 Earning a Living

Growing up in the Depression, for boys who felt its impact, meant exposure to the uncertain aspects of earning a living. The search for employment, queuing for public relief, and rent strikes—these and other events dramatized the struggle to survive, to make a living. One might argue that boys became cautious or conservative men in their worklife as a result of this experience, favoring a steady job over the risks of job mobility, and vesting emotions in the more durable shelter of family relationships; or that hardship fostered work consciousness and commitments in aspirations, a determination to achieve greater material and social benefits, which enabled men to surmount handicaps (such as educational limitations) in their life course. Though seemingly in conflict, these interpretations are mainly distinguished by their reference to different aspects of adult life which have roots in childhood, to the meaning or relative value of activities and the process of status attainment. Our primary objective in this chapter is to determine whether and how these aspects of adult experience are linked in the lives of the Oakland men to family background in the Depression, defined by class origin and economic deprivation.

Any attempt to trace the values of men to experiences in the Depression must take their adult situations into account, since they determine the appropriateness or adaptive value of lessons from the past. Even if boys in the Depression were impressed by the importance of job security, security is unlikely to acquire priority among those who were most successful in their worklife. Men who advanced beyond their father’s status tend to be more committed to the job and less attached to family life or leisure than the nonmobile (see Elder 1969b). Accordingly, we expect the association between family deprivation and adult values (job security, etc.) to increase with the degree of social continuity between the Depression and adult life. An examination of status attainment is thus a first step in identifying the adult contexts of predispositions acquired in the Depression.

Opportunities for social advancement were available in the late 30s to boys who did not pursue education beyond the high school years, but higher education was the most certain route to prestigious jobs, and it was also highly vulnerable to the limitations of family deprivation.1 These limitations are mainly concentrated in the working class of the Oakland cohort, and should be most evident in the educational level of boys from this stratum. Family resources in support for education are the only substantial difference between boys from deprived and nondeprived households; they were similar on ability, desire to excel (on tasks), and occupational goals in each social class.

Educational opportunities relative to family hardships in the Depression are difficult to estimate for boys in the sample since they left home just prior to nationwide mobilization in World War II. In fact, the stirring of economic revival is generally dated from the outbreak of war in Europe in September 1939, just three months after the adolescents left high school. War spurred American markets and industries, generating opportunities and educational options for the young. “It was like watching blood drain back into the blanched face of a person who had fainted.”2 Shortly thereafter a majority of the male members of the 1915-25 cohort were called to serve in the military, and some eventually continued their education through the GI bill.3

These developments in the late 30s are reflected in a general mood of optimism among the Oakland boys when they were questioned at the end of 1938. Only half of the sample participated in the survey, and though all but a few respondents were members of middle-class families, their general outlook is at least suggestive of beliefs at the time. Regardless of family hardship, nearly three-fourths of the boys felt that the Depression, as they had experienced it, was over. The sons of deprived parents were not more discouraged about their future than members of more affluent families, but they displayed more awareness of potential disappointments in life. Exposure to family hardships and suffering in the community had not shaken their belief in the democratic system of government or in the formula of hard work and talent for getting ahead. On the contrary, these boys were more likely to subscribe to beliefs of this sort than relatively affluent youth.

The subsequent analysis is organized around the relation between economic deprivation and life achievement, sources of variation in this relation, and values. In the first section we shall provide an overview of the life course followed by the Oakland mea—defined by marriage, initial employment, parenthood, education, and occupation—and then make comparisons according to family origin and economic loss. This is followed by an assessment of three potential sources of variation in the occupational attainment of men from deprived families: vocational crystallization and commitment, as expressed in worklife patterns; ambition in achievement striving and the utilization of ability; and education. If family deprivation reduced educational prospects for some boys, it also introduced them at a relatively early age to habits, attitudes, and responsibilities which may have proved beneficial in their worklife. Both involvement in productive roles and the insecurity of dependence on deprived parents are conducive to preoccupation with matters of economic support and occupational role, of focused goals and the utilization of skills. Having identified these elements in status attainment, we shall turn to adult values and their relation to experiences in the Depression. Particular emphasis will be given to the relative importance and meaning of work role and family life, the two dominant concerns of men in the Depression.

The sample for our analysis includes sixty-nine boys who participated as adults in at least one of three systematic follow-ups between 1941 and 1965.4 Since the data collections (1953–54, 1958, and 1964) are described in chapter 1 and Appendix B, only two points warrant mention here. First, sample attrition over this time span is not related to class origin, household structure, ethnicity, economic loss in the 30s, or intelligence. Second, information collected in the adult follow-ups was organized in the form of occupational and marital histories through 1958. Since the Oakland sons in 1958 were approximately the same age as their fathers had been in 1929, intergenerational comparisons are based upon comparisons of adult status in these two years.

Adult Status in the Life Course of the Oakland Cohort

Three developments after the Depression decade left a distinct imprint on the career beginnings and life course of the Oakland boys: World War II, the expansion of higher education, and the growth of large-scale organizations and salaried positions in large corporations. Shortly after Pearl Harbor most of the boys were in uniform, and over 90 percent eventually served in some capacity. Organizational growth in the war economy and postwar years is manifested in their subsequent career lines and status achievements.

As a first step in the analys...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Table of Contents

- List of Tables

- List of Figures

- Foreword by Urie Bronfenbrenner

- Foreword by John A. Clausen

- Acknowledgments

- I Crisis and Adaptation: An Introduction

- II Coming of Age in the Depression

- III The Adult Years

- IV The Depression Experiences in Life Patterns

- V Beyond “Children of the Great Depression”

- Appendix A Tables

- Appendix B Sample Characteristics, Data Sources and Methodological Issues

- Appendix C On Comparisons of the Great Depression

- Notes

- Select Bibliography

- Index