1

Mindfulness and Acceptance Approaches

Do They Have a Place in Elite Sport?

Kristoffer Henriksen, Peter Haberl, Amy Baltzell, Jakob Hansen, Daniel Birrer and Carsten Hvid Larsen

As practitioners, we develop our professional philosophies and approaches to sport psychology throughout our careers. Usually this is through small adjustments, but for some, this development can also include major—almost paradigmatic—shifts. In all cases, development is often sparked by specific experiences in working life. When we (the authors of this chapter) discuss our professional development, we can all point to experiences that have stimulated us to rethink our approach to sport psychology intervention. They include:

- Helping athletes regain motivation and find meaning in their endeavors, even in their most successful periods.

- Seeing an athlete, who we consider to be mentally strong, crumble under pressure at the really big show.

- Teaching athletes to deliberately enter an optimal performance state in competitions, only to see them fail in this when it matters the most.

- Realizing that athletes have become more nervous about their anxiety than about their performance.

- Seeing athletes give up the struggle to control their thoughts and emotions and unexpectedly starting to perform beyond their own expectations.

- Successfully helping athletes win medals only to realize there is more to a fulfilling career. We have found that winning medals for some athletes, without love for the sport and pride in the way the medals were won, are unfulfilling accomplishments.

- Losing sight of who we want to be as practitioners and being unable to be fully present with athletes, when we find ourselves under pressure and strain.

Mindfulness and acceptance-based approaches have helped us make sense of such experiences. These approaches provide some of the answers we seek, when we strive to help elite athletes develop their mental game. We believe this may explain why mindfulness and acceptance-based approaches are gaining momentum in elite sport.

Prologue: The Summit

In 2017, Team Denmark hosted the Copenhagen Summit on Mindfulness and Acceptance Approaches in Elite Sport. This summit was the first international event targeting these approaches in international level elite sport. We invited experienced practitioners, not knowing if there would be any interest. We were overwhelmed. Quickly we reached 48 participants from 17 different countries and five continents, and we had to close the list.

Focus of the three-day summit was the application of mindfulness and acceptance approaches in elite sport. The participants were highly experienced sport psychology practitioners. Most of the participants worked in national elite sport organizations, professional teams or similar, and had several years of experience with supporting athletes during key sporting events such as World Championships and Olympic Games.

The summit clearly showed that some of the world’s top sport psychology practitioners have begun to embrace mindfulness and acceptance approaches. The participants willingly shared professional cases, methods and exercises with great enthusiasm.

The summit also showed, however, that the sport psychology profession is still underway with adapting the methods and techniques from mainstream psychology to work in elite sport settings. We had as many questions as we did answers. In search for answers, the second summit was held in 2018 in Magglingen, Switzerland.

The atmosphere of curiosity and sharing stimulated us to plan this book. With so many experienced people who had so many good ideas, and who were so willing to share, we had no choice.

In this introductory chapter, we will set the scene for the book. We will provide an introduction to mindfulness and acceptance-based approaches in elite sport, including the overall ideas, theoretical underpinnings and working models. We will also provide a short review on the state of the art of the research in the area. Finally, we will look at how these approaches are being used by sport psychology practitioners working in elite sport, including two personal stories from experienced practitioners about why they committed to these perspectives in their applied practice.

What Are Mindfulness and Acceptance Approaches Anyway?

The term “mindfulness and acceptance-based approaches” does not refer to a special program or psychological practice. It is a collective description of different behavioral therapy methods and programs that use mindfulness and acceptance as key components.

Behavioral therapy overall aims to (a) produce scientifically based methods of analysis of mental health problems, and (b) develop validated interventions for these problems (Hayes, Luoma, Bond, Masuda, & Lillis, 2006). Historically, these behavior therapies have evolved in what has been termed three waves.

The first wave, traditional behavior therapies, focused solely on behavior and on shaping behavior (e.g., Skinner, 1953). Thinking was given very little attention. Examples are classical and operant conditioning. Evolved in the 1940s, it became an important answer to the needs of the many World War II veterans. It was groundbreaking in that it was a scientifically based and effective short-term therapy. Today, its principles are still used widely in most psychological treatment.

The second wave, Cognitive Behavioral Therapy, or CBT (e.g., Beck, 1995), was stimulated by “the cognitive revolution” in psychology science, and introduced a key focus on thinking and choice. Seeing humans in the image of the computer, these approaches took a key interest in how humans process data. CBT builds on the idea that cognitions are major determinants of how we feel and act, and that psychological problems stem from faulty thinking. The therapist will aim to help the client change dysfunctional patterns of thought-emotion-behavior interactions into more functional ones.

Today, we are facing a perplexing dilemma. On the one hand, life has never been easier (at least in the privileged parts of the world). We live longer. We make more money. We can cure more diseases. We actually have the time and energy to focus on self-development, happiness and a good life. We have access to a wealth of inspiration, such as self-help literature and life coaches. On the other hand, people suffer to an unprecedented degree. Mental ill health such as depression and anxiety is spreading like a wild fire. The World Health Organization estimates that by 2030, depression will be the biggest threat to public health worldwide. The development in elite sport mirrors this dilemma. On the one hand we see better than ever support (financial and expertise). On the other hand time, an increasing number of athletes struggle with their mental health (Henriksen et al., 2019).

The third wave, acceptance and mindfulness-based approaches (Hayes & Strosahl, 2004), are also built on the idea that thinking is an important root of mental ill being. They argue, however, that trying to control our thoughts and emotions is not a part of the solution but rather a part of the problem. Instead, the therapist will aim to help the client accept all (unpleasant as well as pleasant) inner experiences, engage in the present moment and commit to valued behaviors.

Mindfulness and acceptance are closely tied together. Mindfulness has been defined as “paying attention in a particular way: on purpose, in the present moment and non-judgmentally” (Kabat-Zinn, 1994, p. 8). This entails paying attention to external events as well as internal experiences, and as they occur. It is a mental state of presence that allows you to engage with what you are doing in the present moment. It means, for example, observing your thoughts before a competition, without labeling them as good or bad and without the intent to eliminate or change them. Just simply notice. This is opposed to being mindless or being on autopilot, which describes a situation in which you are unaware of what is going on inside and around you. Thoughts race through your mind, and you act on them before you even really notice they are there.

Acceptance means opening up and making room for the full range of thoughts, feelings and sensations, that are a natural part of life and of a sport career—not only the positive ones. Acceptance means to drop the struggle with these emotions, give them some breathing space, and just let them be there without getting overwhelmed. When you learn to accept and open up, it is easier to let feelings come and go without draining your energy or holding you back. In their seminal work on the Mindfulness Acceptance Commitment (MAC) approach in sport psychology, Gardner and Moore (2007) conclude:

it is not the presence or absence of negative thoughts, physiological arousal, or emotions such as anxiety or anger that predicts performance outcomes; rather, it is the degree to which an individual performer can accept these experiences and remain attentionally and behaviorally engaged in the performance task.

(p. 16)

The ACT Model

In mainstream psychology, Acceptance and Commitment Therapy (ACT, pronounced as the word, not the initials) has proven effective (Hayes & Strosahl, 2004). ACT is recognized as an evidence-based practice in mental health treatment by several national mental health boards, including the US-based National Registry of Evidence-based Programs and Practices (see samhsa.gov).

A key idea in ACT is that people (partly due to context and language) end up losing contact with their values and with the present moment. A focus on “feeling good”, strongly rooted in our culture, stimulates people to engage in many behaviors that serve to reduce or eliminate unpleasant thoughts and emotions. An alcoholic may drink to forget. A parent may get lost in his phone (distraction) to avoid conflict with his teenage son. An athlete may over-train to avoid the unpleasant insecurity of having trained enough. And an athlete under pressure in a game-deciding moment may play defensively to avoid the anxiety that is a consequence of taking the necessary risk. These behaviors, however, do not bring us closer to living a rich, full and meaningful life.

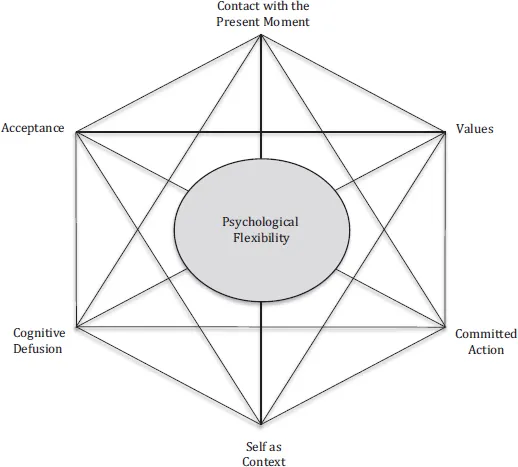

The overall aim in ACT therapies is to help the client develop psychological flexibility, which can be described as “the ability to contact the present moment more fully as a conscious human being, and to change or persist in behavior when doing so serves valued ends” (Hayes et al., 2006, p. 7). In other words, the ACT trainer aims to help people engage in actions that bring them closer to living a valued life, rather than just reduce unpleasant internal states.

ACT establishes psychological flexibility by focusing on six core processes, as illustrated in Figure 1.1. For present purposes, we will only present these processes very briefly to provide an overview. How to work with athletes on each of these processes will be unfolded in the coming chapters.

- Acceptance of private experiences is the active embracing of all human experiences (e.g., thoughts, emotions, urges and memories) without trying to fight them or change their form or frequency, and in the service of response flexibility. Athletes will often strive to not feel nervous or to boost their sense of confidence. If they are willing to experience the full range of emotions that are a natural part of elite sport (also being nervous and unconfident), they are more likely to be able to respond flexibly and values-based to challenges that arise.

- Cognitive defusion is the ability to observe one’s own uncomfortable thoughts without automatically taking them literally; to take a step back, detach from them and let them come and go as if they were leaves floating down a stream. In high-pressure situations, many athletes have thoughts like “I cannot do this” or “anything that is not perfect is not worth doing at all”. Taking such thoughts too literally could make the athletes quit or take certain difficult elements out of their game. But these thoughts are natural and not easily eliminated. A range of techniques has been developed to promote a modified relationship with inner experiences such as thoughts (i.e., to defuse from them) rather than to alter their form or frequency.

Figure 1.1 The ACT Hexaflex Model

- Contact with the present moment means being able to direct attention flexibly and voluntarily to present external and internal events. It is a nonjudgmental awareness of what is going on and the ability to engage with what happens is the moment. Athletes will often find their attention is automatically drawn to the past (“why did I miss that point?”) or future (“If I lose this game, I may not be able to …”). Or the mind simply wanders, like when they open a snack bar, take a bite and suddenly realize all they have left is the empty packet. It is easy to lose awareness in modern life. Mindfulness training is a key element in learning to direct attention and be present.

- Self as context refers to a perspective-taking sense of self and being in touch with a sense of ongoing awareness. This is opposed to a strong attachment to a conceptualized self. Athletes may find themselves very attached to concepts about who they are. These include ideas such as “I win through creative play”. A strong attachment to such concepts stands in the way of developing flexible responses that fit the current context. After a 250 km race, a competitive cyclist attempted to escape in a strong head wind 2 km before the finish line, simply because he was fused with the idea that he is not a sprinter. In reality, everybody was tired, no one had a good sprint at this point in the race and going alone against the wind was doomed to fail.

- Values refer to the identification of values that are personally important. What do you want to stand for in life? Values are guidelines for behavior. Unlike goals, they can never be reached, but can be pursued throughout life. Some athletes do not know why they do their sport, or what they would like their sport career to be about beyond results. A strong connection with values not only brings satisfaction. It is also an important resource in times of adversity.

- Committed action is the commitment to actions that help bring us closer to our valued ends. It is where the rubber meets the road. In a busy schedule, athletes may quickly forget their commitment to their values. Mental training is a good example: “I know I promised myself to take my mindfulness training seriously, but the last game went well, so I will skip it today”. Like in all behavioral therapies, helping clients take committed actions requires setting clear behavior change goals and translating values to specific behaviors.

ACT is not a specified program with a certain number of steps. It relies on a skilled practitioner making good decisions about what processes to target and in what order. Steve Hayes, the founder of ACT, has jokingly called ACT the evidence-based method for people who don’t like evidence-based methods. As you will see throughout the book, ACT is an experiential approach, which relies heavily on exercises, experiences and metaphors.

ACT and Mindfulness Works: The Roots

Our interest in mindfulness and acceptance-based approaches in sport is founded on strong evidence from general psychology research and on burgeoning support within the field of sport psychology. These interventions are conceptually based or begin with the mindfulness definition of Jon Kabat-Zinn (1994) (i.e., an intentional, present moment acceptance of experience) and some on Ellen Langer (1989) (i.e. noticing new things, accepting the continuously changing nature of circumstances and flexibly shifting perspectives in accordance with changing contexts). From a classic psychological perspective, mindfulness is referred to as a trait (being mindful in everyday life), a state (being mindful in the present moment) and a training (tools to foster state and trait mindfulness). In this sense, “mindfulness is a quality of awareness that objectifies the contents of experience, internally and externally, promoting greater tolerance, interest and clarity towards that content” (Baltzell & Summers, 2016, p. 527). In this regard, three different processes of mindfulness are seen as important mindfulness components (Birrer & Röthlin, 2017): (a) purposeful present-moment awareness, (b) metacognitive awareness (consciously being aware of whatev...

Figure 1.1 The ACT Hexaflex ModelSource: Copyright Steven C. Hayes. Used by permission.

Figure 1.1 The ACT Hexaflex ModelSource: Copyright Steven C. Hayes. Used by permission.