eBook - ePub

Captive Selves, Captivating Others

The Politics And Poetics Of Colonial American Captivity Narratives

- 280 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Captive Selves, Captivating Others

The Politics And Poetics Of Colonial American Captivity Narratives

About this book

This book considers two key typifications within the Anglo-American captivity tradition: the Captive Self and the Captivating Other. It analyzes a hegemonic tradition of representation and illuminates the processes through which typifications are constructed, made authoritative, and transformed.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Captive Selves, Captivating Others by Pauline Turner Strong in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & World History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

Introduction: Captivity As Convergent Practice and Selective Tradition

Tradition is in practice the most evident expression of the dominant and hegemonic pressures and limits. It is always more than an inert historicized segment; indeed it is the most powerful practical means of incorporation. What we have to see is not just ‘a tradition but a selective tradition; an intentionally selective version of a shaping past and a pre-shaped present, which is then powerfully operative in the process of social and cultural definition and identification.

—Raymond Williams, Marxism and Literature (1977:115)

In a selective tradition that dates to the seventeenth century, Anglo-American identity is represented as the product of struggles in and against the wild: struggles of a collective Self surrounded by a threatening but enticing wilderness, a Self that seeks to domesticate this wilderness as well as the savagery within itself, and that opposes itself to Others portrayed as savage, bestial, demonic, and seductive. Originally an outgrowth of the Puritan penchant for defining the individual and collective Self through opposition to presumably uncivil, ungodly Others, this remarkably resilient fabrication of identity took shape during the century of colonial wars preceding the American Revolution. In the course of extended struggles among English, French, Algonquian, Iroquoian, and other groups for control over northeastern North America,1 a significant number of English colonists were taken captive by Native Americans. For the Puritan colonists of New England, who were continually searching for signs of the work of Providence in the world, these captivities came to epitomize the spiritual trial posed to the colonists by the American wilderness, its savage inhabitants, and perhaps most importantly, the savagery within themselves. By the mid-eighteenth century, colonists were representing the experience of captivity among Indians in a more variegated fashion while continuing to find in captivity a compelling representation of an emerging American Self undergoing assault and transformation.

The most famous Anglo-American narrative of captivity among Indians, by Capt. John Smith, dates to his Generall Historie of 1624. Initially more influential in the development of a selective tradition of captivity, however, was a late seventeenth-century spiritual autobiography recounting the wilderness trials and redemption of a clergyman’s wife, Mary White Rowlandson, who was taken captive in 1676 during Metacom’s War (or “King Philip’s War”). Over the next half century the spiritual significance of captivity in the wilderness would be developed in a corpus of widely disseminated narratives by or about Puritan and Quaker captives, mainly women. Another dozen narratives of captivity were published during the remaining decades of the colonial era, for the most part during or immediately following the fourth intercolonial war (or “French and Indian War”), of 1754–63.2 In contrast to Puritan and Quaker captivity narratives, mid-eighteenth-century narratives are often secular accounts by male prisoners of war.

After Independence two dozen additional narratives by or about colonial captives were published, culminating in the unusual life history of Dehewamis or Mary Jemison (1824), an adopted and thoroughly assimilated English captive among the Seneca. Meanwhile, from the late eighteenth century onward, post-Revolutionary captivity narratives, anthologies, visual representations of captivity, and completely fictional accounts became common. Approximately two dozen fictional treatments of captivity, often based on John Smith’s account of his rescue by Pocahontas, preceded the publication in 1826 of James Fenimore Cooper’s classic The Last of the Mohicans.3 Since Cooper, the captivity theme has persisted in Anglo-American literature and popular culture as a pervasive mode of representing a distinctively Euro-American identity. The selective tradition of captivity has expanded from print to drama, public sculpture, children’s games, film, and television, remaining today an implicit model for representations of threatening otherness.4

In sharp contrast to the dominant representation, captivity was practiced in both directions across the border between Native and colonial societies—a border that was considerably more fluid than it appears in most historical representations. The practice of captivity in what Pratt has called the “contact zone” (1992) has an extraordinarily complex history: one that extends back not only to the beginning of the European invasion of North America but beyond, since indigenous practices of captivity themselves were borderland phenomena. This book focuses on only a portion of that history: captivity across the British–Native American borders during the two centuries between 1576 and 1776. These were years of intensive exploration and colonial settlement, transformative interaction, and intermittent warfare, involving several indigenous wars of resistance5 as well as four intercolonial wars between Britain and its indigenous allies, on the one hand, and France and its allies, on the other.

This book has three main aims: First, I analyze the representations of the collective Self and its significant Others that colonial Anglo-Americans developed in their accounts of captivity among Indians. Second, I attempt to demonstrate that captivity itself was a complex practice in which various indigenous and European traditions of mediation, redemption, and revitalization converged. Third, I explore the relationship between captivity as a historical practice and captivity as represented in what I call the selective or hegemonic tradition of captivity. I maintain that it is in large part through the suppression of the complexity of captivity as a practice—and particularly the suppression of the colonists’ role as captors of Indians—that the selective tradition of captivity has gained its ideological force. In order to look closely at the relationship between colonial practice and representation I have confined my analysis to the years preceding the Revolutionary War.

Situating my study in the nexus of practice and representation has required me to bring together three scholarly traditions that are in themselves already interdisciplinary: ethnohistory, women’s studies, and American cultural studies. The next section introduces my theoretical and methodological approach, and the one that follows it relates my approach to previous scholarship on the practice and representation of captivity. The introduction closes with a brief overview of the book, highlighting the central tales of captivity that will be told and retold. Readers who are more interested in the substance of the book than in its theoretical moorings and ambitions may wish to turn directly to the overview.

Identity, Alterity, and the Process of Typification

HERE LIES THE BODY

OF LIEUT MEHUMAN HINSDELL

DECD MAY YE 9TH 1736.

IN THE 63D YEAR OF HIS

AGE. WHO WAS THE FIRST

MALE CHILD BORN IN THIS

PLACE AND WAS TWICE CAPTIVATED

BY THE INDIAN SALVAGES

—Tombstone in Deerfield, Massachusetts (formerly a Pocumtuck Indian town) (Baker and Coleman 1925)

In American literary history the genre called, curiously enough, “Indian captivity narratives” has been considered the first indigenous literary tradition. That colonial literature appears in the scholarship as indigenously American indicates the extent to which captivity among Indians is part of an exclusionary and appropriative tradition. Indeed, Raymond Williams’s definition of a hegemonic tradition may be taken as a condensation of the problematic that motivates this study. For Williams a tradition is a “radically selective” and “actively shaping force” that is “intended to connect with and ratify the present.” It is, in particular, “powerfully operative in the process of social and cultural definition and identification” as well as exclusion (Williams 1977:115–116). If representations of captivity comprise a hegemonic tradition in this sense—as I attempt in this book to demonstrate—a critical analysis of this tradition must have at least four dimensions. It must (1) analyze the tradition’s “shape” or structure, identifying the principles of selection that order this particular version of the past; (2) contextualize the tradition within a broader field of intercultural practice, revealing crucial elements that the tradition excludes or obscures; (3) locate the tradition socially, indicating the combination of position, perception, interest, and influence that have given the tradition its distinctive shape and connection to the present; and (4) relate the tradition, thus defined, to alternative traditions and to the ongoing process through which social and cultural identity, difference, and domination are constructed and contested. Considering all of these dimensions of the selective tradition of captivity requires a combination of textual and ethnohistorical analysis.

Williams’s definition of tradition is a development and specification of one significant dimension of Antonio Gramsci’s concept of cultural hegemony.6 The captivity tradition may be considered what Williams calls an “element of a hegemony” (1977:111), insofar as it is part of the process through which a dominant social group legitimates its power by grounding it in a set of authoritative understandings. These understandings are taken for granted, and they permeate and structure lived experience. Alfred Schutz, a phenomenological theorist of the “natural attitude” of everyday experience, called such naturalized, taken-for-granted understandings “typifications”—a term I have adopted to refer to the conventional representations employed in the captivity tradition.7 The two most significant typifications in this tradition are an oppositional pair that I call the Captive Self and the Captivating Other (the Captivating Savage, in colonial terminology).

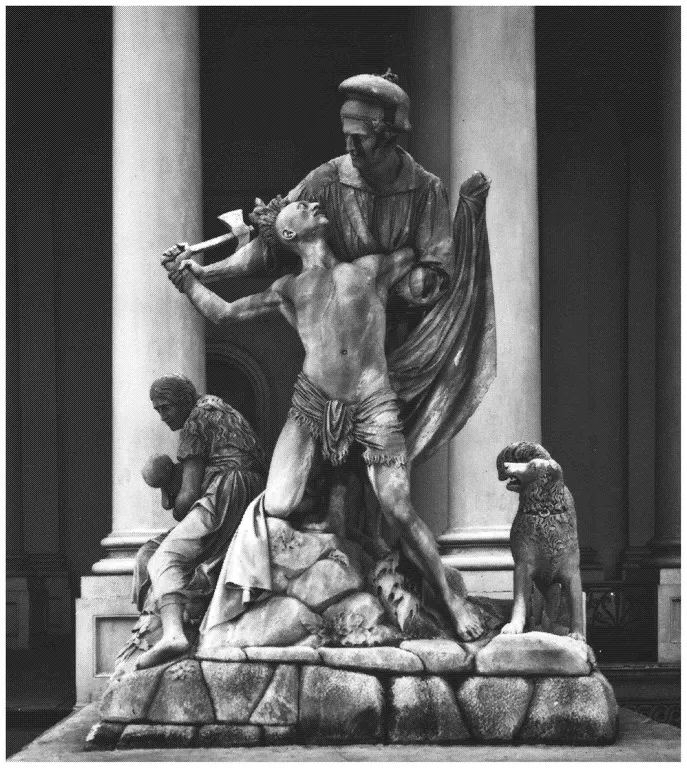

A particularly revealing visual representation of these typifications, Horatio Greenough’s The Rescue (see Figure 1.1), stood for a century at the east entrance to the U.S. Capitol Building, until its removal in 1958. In this monument to triumphant nationhood, a fully and archaically clothed European male rescues a partially disrobed woman and her child from the uplifted tomahawk of a naked male Indian. Skillfully deploying oppositions in race, gender, civility, and rationality, Greenough’s sculpture both depicts the vulnerability of European civilization in the American wilderness and legitimates the nation’s use of force against savage Others.8

FIGURE 1.1 The Rescue, by Horatio Greenough, displayed at the east entrance to the U.S. Capitol Building between 1853 and 1958. Source: Architect of the Capitol.

As we will see, the Captive Self, Captivating Other, and Noble Redeemer sculpted by Greenough are conventional representations thoroughly embodied in a hegemonic tradition—that is, they are typifications. I use this term rather than certain more common but less revealing alternatives—images, stereotypes, figures, tropes—in order to emphasize the relationship among analytical abstractions (my own Captive Self and Captivating Other), artistic or literary abstractions (Greenough’s figures, for instance), and the socially constructed “natural attitude” or “habitus” (Bourdieu 1977) of lived experience. To explain: Schutz’s concept of typification extends the Weberian notion of “ideal type” to the socially constructed “natural attitude” of lived experience. Although Weber himself was particularly interested in establishing the value and status of ideal types in social science, he considered the theorist’s “ideal typical representations” or “conceptual constructs” more systematic, internally consistent, and consciously formulated versions of the “collective concepts” and “naturalistic prejudices” of everyday life.9 Both common sense and theoretical concepts are abstractions in Hegel’s sense—one-sided, simplified perspectives of the infinite complexity of the concrete, which accentuate certain situationally relevant aspects of experience. The Captive Self and Captivating Savage of my analysis, then, are second-order analytical typifications that synthesize and abstract from the various first-order typifications of colonial captives and Indian captors found in the captivity tradition, and that both constitute and reflect the lived experience of captivity.10

Schutz called attention to the need for studies of the typifications of those treated as Others because they do not participate in the same culturally constructed natural attitude.11 One such study, explicitly based on Schutz, is Keith Basso’s (1979) exemplary monograph on Western Apache typifications of “the Whiteman.” Basso analyzes how Western Apache jokes typify or “epitomize” dominant Others by highlighting oppositions between Anglo-American and Apache behavior. Using the sociolinguistic concepts of structural opposition and poetic foregrounding, Basso demonstrates how Western Apache typifications of “the Whiteman” select behavioral elements for their contrast with those of the ideal Apache Self, distorting the selected elements so as to heighten the contrast.

This book, in a complementary fashion, considers two key typifications within the Anglo-American captivity tradition: the Captive Self and the Captivating Other. In addition to analyzing a hegemonic tradition of representation, I seek to illuminate the processes through which typifications are constructed, made authoritative, challenged, and transformed. In considering the conditions under which typifications are resisted, I draw on Gramsci’s concept of alternative or oppositional hegemonies. These hegemonies challenge the dominant ideology, most often in derivative terms.12 The complexity and dynamism of the concept “cultural hegemony” resides in its recognition of the importance of alternative or oppositional hegemonies, their dependence on the hegemonic, and their vulnerability to efforts to incorporate and diffuse them. When dealing with genuinely multicultural interactions such as those considered here, however, resistance and opposition draw on competing hegemonies that are far more radically alternative than in the situations of class conflict explored by Gramsci. In the British-Native American contact zone, various European, Iroquoian, and Algonquian traditions of captivity competed and to some extent converged.

In scholarship as in hegemonic representation, captivity has often been decontextualized such that it is viewed as a distinctively Indian practice rather than as a complex historical phenomenon affected in significant ways by European colonial discourses and practices. ...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Dedication

- Contents

- List of Maps and Figures

- Chronology of Events, 1576–1776

- Preface and Acknowledgments

- A Note on the Text

- 1 Introduction: Captivity As Convergent Practice and Selective Tradition

- 2 Indian Captives, English Captors, 1576–1622

- 3 Captivity and Hostage-Exchange in Powhatan’s Domain, 1607–1624

- 4 The Politics and Poetics of Captivity in New England, 1620–1682

- 5 Seduction, Redemption, and the Typification of Captivity, 1675–1707

- 6 Captive Ethnographers, 1699–1736

- 7 Captivity and Colonial Structures of Feeling, 1744–1776

- Appendix: Bibliography of British and British Colonial Captivity Narratives, 1682–1776

- References

- Index