- 208 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

In this trenchant work, Susan Bennett examines the authority of the past in modern cultural experience and the parameters for the reproduction of the plays. She addresses these issues from both the viewpoints of literary theory and theatre studies, shifting Shakespeare out of straightforward performance studies in order to address questions about his plays and to consider them in the context of current theoretical debates on historiography, post-colonialism and canonicity.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

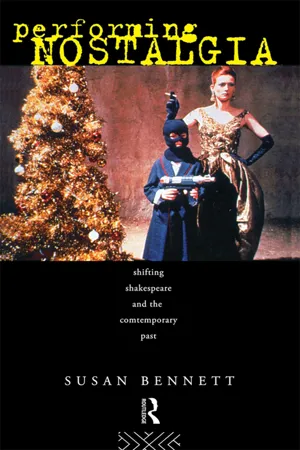

Yes, you can access Performing Nostalgia by Susan Bennett in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Medios de comunicación y artes escénicas & Artes escénicas. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

NEW WAYS TO PLAY OLD TEXTS

Discourses of the Past

The past is only a figure of the desire of the present.

(Lucia Folena 1989: 221)

This is the true Shakespearian wood – but it is not the wood of Shakespeare’s time, which did not know itself to be Shakespearian, and therefore felt no need to keep up appearances. No. The wood we have just described is that of nineteenth-century nostalgia, which disinfected the wood, cleansing it of the grave, hideous and elemental beings with which the superstition of an earlier age had filled it. . . . However, as it turns out, the Victorians did not leave the woods in quite the state they might have wished to find them.

(Angela Carter 1986: 69)

If the past is a foreign country, nostalgia has made it ‘the foreign country with the healthiest tourist trade of all.’

(David Lowenthal 1985: 4)

INTRODUCTION

That global industry of remarkable energy and profit – Shakespeare – provides perhaps the very best symptom of a present-day epidemic, the past. This book takes up the (dis)articulation of the past through the cultural apparati that produce Shakespeare (the man, his plays, his times) in order to locate some of the issues involved in and explored by contemporary performance. Many of the performances constituting this discussion fall explicitly under the categorization usefully invoked by Jonathan Dollimore, ‘creative vandalism.’1 They take up a deliberately antagonistic relationship to their source text(s) as well as to the operations under which that source is generally produced and/or received. What happens, then, is that both the gaps and the excesses of the Shakespeare corpus become the foundation for a performance of the present. While those gaps and excesses are always inherent, even in a ‘straight’ production/reading of a Shakespeare play, it is when they become the text that their inclination to disrupt the notion of the linearity of progress is made manifest. And this is a trajectory which Michel de Certeau, more broadly, locates for the writing of history:

[W]hatever this new understanding of the past holds to be irrelevant – shards created by the selection of materials, remainders left aside by an explication – comes back, despite everything, on the edges of discourse or in its rifts and crannies: ‘resistances,’ ‘survivals,’ or delays discreetly perturb the pretty order of a line of ‘progress’ or a system of interpretation. These are the lapses in the syntax constructed by the law of a place. Therein they symbolize a return of the repressed, that is, a return of what, at a given moment, has become unthinkable in order for a new identity to become thinkable

(de Certeau 1988: 4)

It is the inevitable and symbiotic relationship between the writing of the past and the performance of the present that (in)forms the subject of this book.

The chapters that follow involve a negotiation between the unthinkable and the thinkable through the mechanism of the apparently very well known. They concern themselves with the effects of proliferation on performances of textual truth and history; with active representations of transgression, dissidence and desire which enact a longing for at least micropolitical change; and with surveillance of the errant and disobedient bodies which persist in their urge to be seen. I do not mean the readings, the questions raised here, to be specific only to the dissemination of Shakespeare, merely to suggest that it is in ‘Shakespeare’ that they are most acutely and vividly posed.

But, as a preliminary manoeuvre, it is useful to log and account for the obsessiveness with which the past has its selves performed in the contemporary moment. Don Wayne has argued that ‘[t]here has been a noticeable lag between our ability to recognize the role of power in the plays and poems of Shakespeare and his contemporaries, and our ability to articulate the forms that power takes in our own historical moment’ (1987: 58). And, viewed from the perspective of literary and/or theatre studies, this is arguably so. With another lens, however, the role of power in contemporary cultures is frankly less obscure. If academic criticism has been slow to examine contemporary (play) texts which read the operations of power in their own historical moments, the texts themselves display an obsessive interest in the past as a figure for the desires of the present. In other (non-literary) disciplines, both the apparent stability and the very real anxieties of the dominant Western cultural body are revealed by the insulation of that same body through the dissemination of ‘protective and narcissistic illusions’ of a common past (Robins 1991: 44). Often what is perceived as ‘lost’ is reasserted by its cultural representation. The strategy of this particular text is to examine the performance of the past in different agencies of public meaning and to question how particular vested interests project their desires for the present (and, indeed, the future) through a multiplicity of representations of past texts as well as through the attempt to trespass into already-(over)coded traditions.

Yet why is it, to recycle David Lowenthal’s words which appear at the opening of this chapter, that there is, engaged with and in the past, such a healthy – or even potent – tourist trade? How has it happened that these global consumers have been persuaded to travel to and through the past? Is this epidemic production/consumption of historical texts necessarily only ‘evidence of a process of economic and cultural decline: a systematic substitution of replica for reality, simulation for experience, enactment for lived history’ (Holderness 1992a: 248)?

The once monolithic History of great men and major events has, as we know, in recent years been dispersed into a multiplicity of histories which compete with greater and lesser success in representing the past and which do so in the awareness of what Louis Montrose calls ‘the textuality of history’:

we can have no access to a full and authentic past, a lived material existence, unmediated by the surviving textual traces of the society in question – traces whose survival we cannot assume to be merely contingent but must rather presume to be at least partially consequent upon complex and subtle social processes of preservation and effacement; and . . . those textual traces are themselves subject to subsequent textual mediations when they are construed as the ‘documents’ upon which historians ground their own texts, called ‘histories’.

(1989: 20)

If such a self-consciousness about historiographic writing has reshaped not only the methods but the kinds of histories that are written (and I share Montrose’s caution that ‘History,’ like the ‘Power’ Don Wayne invokes, is ‘in constant danger of hypostatization’ [Montrose 1989:20]), this has not, however, prevented a determined attempt to preserve a single vision of History, of a past which forms a continuous trajectory into the present and through into the future. The representation of a seamless past has, not surprisingly, been an important strategy in the politically regressive governments of the New Right (most obviously in the United Kingdom and America). From Margaret Thatcher, Britons heard:

First, we are more than a one-generation society. As Edmund Burke put it, people who never look backward to their ancestors will not look forward to posterity. We are interested in keeping the best of the past, because we believe in continuity. . . . Second, we are conserving the best of the past.

(cited in Kaye 1991: 95)

Ronald Reagan made much the same point in his 1981 commencement address:

My hope today is that in the years to come and come it [sic] shall – when it’s your turn to explain to another generation the meaning of the past and thereby hold out to them the promise of their future, that you’ll recall the truths and traditions that define our civilization and make up our national heritage. And now, they’re yours to protect and pass on.

(cited in Kaye 1991: 97)

While the well-documented rhetoric of these two national leaders provides an undisguised affirmation of the power of a traditional history, what is more interesting is translation of that rhetoric into a popular demand for the past. Almost incognizant of the crisis of ‘History’ being played out in the academy, the Western world has, in the last decade or so, disseminated a powerful notion of duty to the past, the possession of which through cultural property in the form of commodity fetishism is used to shore up and maintain the status quo. And this duty to the past is, necessarily, not to any authentic representation of earlier events or values, but is instead situated through a nostalgia for that authenticity which is not retrievable. As Lowenthal describes, ‘[a] perpetual staple of nostalgic yearning is the search for a simple and stable past as a refuge from the turbulent and chaotic present’ (1989: 21).

The age of so-called postmodernity in which we live has been described as ‘a kind of macro-nostalgia’ (Chase and Shaw 1989a: 15) where consumers vie for a diverse but eclectic range of commodities with which to anchor their experience and desires. In its most restricted forms, nostalgia performs as the representation of the past’s ‘imagined and mythical qualities’ so as to effect some corrective to the present (Walvin 1987: 162). The taste or appetite for nostalgia, in such readings, gets used as the requisite evidence that ‘we find ourselves living to a great extent in a cultural and emotional vacuum’ (Rubens 1981: 150). This simplified notion of the effect/effectiveness of nostalgia relies on its function as a marker of both what we lack and what we desire; expressed another way, nostalgia is constituted as a longing for certain qualities and attributes in lived experience that we have apparently lost, at the same time as it indicates our inability to produce parallel qualities and attributes which would satisfy the particularities of lived experience in the present. In fact, in all of its manifestations, nostalgia is, in its praxis, conservative (in at least two senses – its political alignment and its motive to keep things intact and unchanged): it leans on an imagined and imaginary past which is more and better than the present and for which the carrier of the nostalgia, in a defective and diminished present, in some way or other longs. This dynamic of the good past/bad present is, as Fred Davis points out, nostalgia’s ‘distinctive rhetorical signature’ (1979: 16). Moreover, collective nostalgia can promote a feeling of community which works to downplay or (even if only temporarily) disregard divisive positionalities (class, race, gender and so on); when nostalgia is produced and experienced collectively, then, it can promote a false and likely dangerous sense of ‘we’ (Davis 1979: 112). Yet the attractions of such a performance cannot be easily ignored in the contemporary moment. The attractions reside especially in the rigor of displacing individual pasts (realized in part through a more private nostalgia) into a collective nostalgia which is often highly and powerfully regulatory. The optic of nostalgia insists, with all inherent dangers, upon a stable referent (Doane and Hodges 1987: 8).

In such a context, it is useful to recall that nostalgia comes with a particular history as diagnostic category. The term was first designated at the end of the seventeenth century to account for physical symptoms registered as a result of the psychic experience of homesickness.2 Davis suggests that nostalgia has, in this century, been demedicalized (1979: 4), but it is perhaps yet necessary to retain something of the sense of its root in a physical condition. The invention of a Swiss doctor, nostalgia came into being first through its anchoring in language (by naming as a disease something that is more than mere homesickness) and subsequently through the description of a cure for the bodies so afflicted. For, after all, nostalgia retains its currency as an affliction – it is what apparently occupies an empty space that a more productive cultural and emotional life is supposed to satisfy. As Susan Stewart has named it, ‘nostalgia is the desire for desire’ (1984: 23). Stewart’s argument is an important one in staging the ideological foundations of nostalgia; she asserts:

the past it [nostalgia] seeks has never existed except as narrative, and hence, always absent, that past continually threatens to reproduce itself as a felt lack. Hostile to history and its invisible origins, and yet longing for an impossibly pure context of lived experience at a place of origin, nostalgia wears a distinctly utopian face.

(1984: 23)

Lowenthal makes a related point in his corrective to British and American theorists who imagine nostalgia to be rampant only in their own cultures and times. Noting that ‘[y]earning for a lost stage of being is part of the fabric of modern life the world over,’3 he insists that ‘[t]he view of nostalgia as a self-serving, chauvinist, right-wing version of the past foisted by the privileged and propertied likewise neglects half the facts. The left no less than the right espouses nostalgia’ (1989: 27).4 This almost universal utopianism would indeed seem to be characteristic, and the pervasiveness of nostalgia across time, gender, class, race (among others) gestures at its own inherent resistance to the dominant paradigms of History that Stewart has referred to. Where it might be that ‘[n]ostalgia for a lost authenticity is a paralyzing structure of historical reflection,’ its function as a conduit for the ‘authentic and inauthentic experience’ of any particular social group or individual means that its symptoms, its practice and, indeed, any attempts to effect a cure remain close to a writing of H/history that assumes the possibility of retrieval of an authentic past (Frow 1991: 135, 136). Thus, when Janice Doane and Devon Hodges set up their important and timely investigation of nostalgia and sexual difference, as a means of accounting for a backlash economy that would curtail the practices of contemporary feminism, they unfortunately retain a rather monolithic use of nostalgia which ignores the subtleties of its different, but no less prevalent, uses across gender as well as (other) forms of discourse.5

Nonetheless, nostalgia at its most virulent has been the property of the Right in the Western world and, in a British context at least, it is conspicuous how often Shakespeare performs the role which links the psychic experience of nostalgia to the possibility of reviving an authentic, naturally better, and material past. And this nostalgic production is not limited to the recent past; after the First World War, Stephen Graham suggested:

In England and Scotland also, it is noticeable that the war has given us a truer perspective and cleared away the Lilliputian obstructions of modern life. We see Shakespeare great and wonderful again, and our mockers of Shakespeare shrink to figures like those men made of matches that used to appear on Bryant & May’s match-boxes.

(cited in Wright 1985: 24)

Cautionary words indeed – but which, despite Graham’s intentions, evidence that there is no greater ‘truth’ in the postwar perspective, only a particular battle for a so-called authentic representation of the past as the present. While it is ‘true that we “make up” history, we do not have full and arbitrary latitude to make it up as we please’ (Abu-Lughod 1989: 126).

Nostalgia might best be considered as the inflicted territory where claims for authenticity (and this a displacement of the articulation of power) are staged. The shifted Shakespearean texts of this book, then, are all profoundly and essentially nostalgic. They situate a desire for desire and it is the very terms under which and for whom such desire is spoken, embodied and subsequently read that I would insist obliges our more careful attention. If there can be fostered a much more elastic and pervasive comprehension of nostalgia, it is perhaps also possible to liberate that felt lack. This might enable re-memberings which don’t, by virtue of the categorization, conjure up a regressively conservative and singular History.

So how do ‘we,’ both collectively and individually, remember the past? What is the connection between those brute events that once did take place at some or other present moment, the making-up of narratives designated as their history, and a...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Author biography

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Contents

- Dedication

- Acknowledgements

- 1 New Ways to Play old Texts

- 2 Production and Proliferation

- 3 Not-shakespeare, our Contemporary

- 4 The Post-Colonial Body?

- 5 Asides

- Notes

- Bibliography

- Subject Index