Introduction

Britain and Ireland, two lands equally blessed with natural assets, are the largest members of an archipelago off the north-west edge of continental Europe that also includes smaller offshore islands in the south, west and north. The whole has been referred to as the ‘British Isles’, inaccurately since Ireland was never British.1 This book is focussed on the island of Britain, as opposed to Britain and Ireland, mainly because a magnificent compendium on early medieval Ireland has just appeared, following a period of intense archaeological investigation.2 The present survey has required frequent glances across the Irish Sea, and the two studies together will hopefully reveal something of that special power of difference that can inspire mutual admiration in close neighbours.

Since Britons also lived in Brittany, the term ‘Great Britain’ referred to its larger land mass, rather than its magnificent achievements on the world stage, a tenderly nurtured delusion.3 The Britons themselves were a heterogeneous people, composed of several groups, including the Picts, the Welsh and the Britons of the south-west, seasoned by four centuries of immigration from the parts of the Roman empire, soon to be joined by the English in the south-east and by the Irish in west Wales and Scotland. Britain was already a mixed race in the 5th century, this being probably the basis for its ingenuity and resilience.

This chapter sets the scene for an exploration of Formative Britain by reviewing the legacy that its peoples inherited: the natural assets of the land and the seas and the relict landscape of the earlier inhabitants. We will find that terrestrial regions define themselves quite easily and that they are still with us; that their character was determined by nature and prehistory, and their experience in the Formative period was modulated by neighbours across the nearest sea, neighbours who were often immigrants and sometimes invaders; and that Britain, far from being a self-contained entity, was a frontier zone where vigorous cultures met.

The natural inheritance: the seas

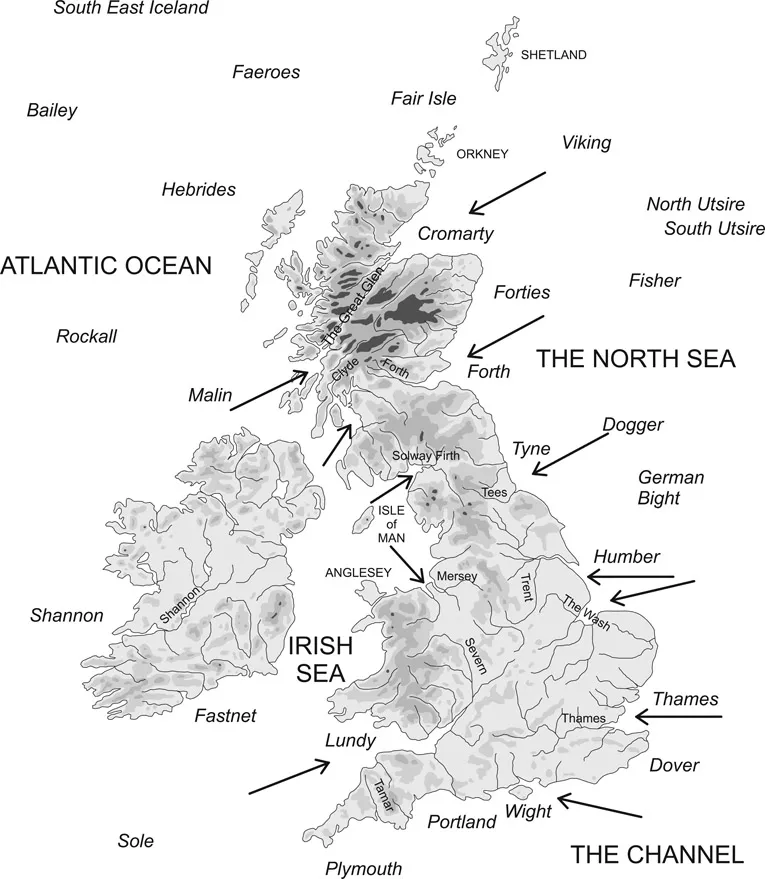

Britain is surrounded by three seas, the North Sea, the Channel and the Irish Sea, plus the Atlantic Ocean, and these are divided into 14 inner ‘sea-areas’ surrounding Britain, all bearing names familiar to late-night listeners to the BBC shipping forecast (Figure 1.1). To get a feel for the seas, we can take an imaginary trip on the 30 m-long ship found in Mound 1 at Sutton Hoo, which had up to 40 oars and probably a sail.4 Although small by yachting standards it remains the largest vessel known to early medieval Europe before the 11th century; it was open to the sky, had a simple steering oar (a ‘steerboard’ on the starboard (right-hand) side) and a freeboard (distance from the gunnel to the waterline amidships) of half a metre.

Figure 1.1 Britain and its neighbours with the location of sea areas (in italics), showing main rivers and principal points of entry.

Proposing a departure from Portmahomack in Easter Ross, we pass down the east coast of Britain, from north to south, through Cromarty, Forth, Tyne, Humber, Thames – all these names reporting the main gateways into the island via firths in the north and estuaries in the south. We take a right turn down the Channel through Dover, Wight, Portland and Plymouth, although only Southampton water, protected by the Isle of Wight, provides a well-protected entry point. Around the perilous cape of Land’s End we head up the Irish Sea through sea areas Lundy, Irish Sea, Malin and Hebrides, passing the major gateways of the Severn, the Mersey, the Solway Firth and the Clyde, through the dense patterns of the western isles to the northern isles (Fair Isle) and round John O’Groats back to Cromarty. The outer sea areas report districts known to more adventurous, far-ranging mariners: Viking, Utsire, Forties, Fisher, Dogger, German Bight in the eastern sea; Fastnet, Shannon, Rockall in the west; Bailey, Faeroes and south-east Iceland in the north.

Wind and water

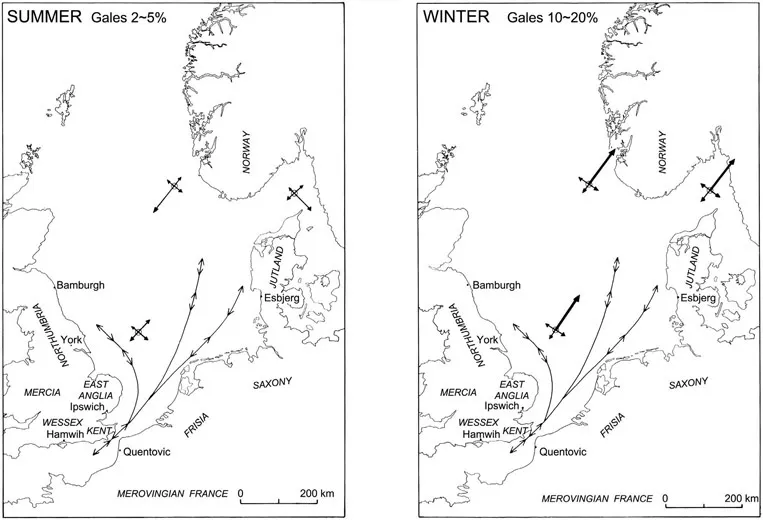

Figure 1.2 Tide and currents (narrow lines) and seasonal prevailing winds in the North Sea.

The politics and prosperity of the archipelago were contingent on how easy it was to travel by sea; and this in turn was dependent on a mariners’ package comprised of the natural environment, the technology of boats and navigational skills. We know a little bit about each of these. Situated between the continent and the ocean, the natural forces of swell, current, tide and wind tend to create thoroughfares that differ with the time of year. In the North Sea, winds in spring favour the traveller from Scandinavia, and in autumn they blow them home5 (Figure 1.2). But in winter, while winds theoretically favour northward travellers, the seas are dangerous. The strongest storm force winds (7–10) are recorded for the months of October to December, and they blow from the west, south-west (in the Channel) and north-west (in the north).6 An open boat would be threatened by winds of Force 5 or more, so North Sea travellers did not generally put to sea after October. The early English sailors put to sea again in March, traditionally prompted by the arrival of a perennial spring visitor: ‘the cuckoo calls, urging the heart onto the whales’ road’.7 The physical effects of these winds, so pertinent to travel and survival in the early middle ages, are today summarised by the Beaufort scale (Table 1.1). The North Sea is thus a thoroughfare rather than a barrier, but it is a thoroughfare that favours Scandinavian traffic. The tidal currents are at their fiercest where canalised in the Straits of Dover. The North Atlantic Drift, a spin off from the Gulf Stream, brings warm surface water past the Iberian peninsula through the Irish Sea to the Orkneys, marking out an ancient thoroughfare that has carried people and ideas from the south to the north of Europe since the Neolithic.8

Table 1.1 Beaufort Scale of wind speed, with effect on a sailing smack

| Name of wind | ONLAND | ON SEA | Speed of a FISHING SMACK |

|

| 0 Calm | Smoke rises vertically | Like a mirror | Becalmed |

| 1 Light air | Smoke shows wind direction | Ripples | Just has steerage way |

| 2 Light breeze | Wind felt on face | Small wavelets. Crests look glassy | Sails filled speed 1-2 kn |

| 3 Gentle breeze | Leaves in motion | Crests begin to break | Smacks tilt at 3-4 kn |

| 4 Moderate breeze | Raises dust | White horses fairly frequent | Carry all canvas with good list |

| 5 Fresh breeze | Small trees sway | Moderate waves, some spray | Smacks shorten sail |

| 6 Strong breeze | Whistling heard in wires | Large waves. White foam crests everywhere | Double reef in mainsail |

| 7 Near gale | Whole trees in motion | Sea heaps up and white streaks show direction of the wind | Smacks lie-to or stay in in harbour |

| 8 Gale | Twigs broken off trees | Long waves, spindrift, well-marked streaks | All smacks make for harbour |

| 9 Strong gale | Chimney pots blown off | High waves topple, tumble and turn over. Spray may affect visibility | |

| 10 Storm | Trees uprooted | Very high waves; whole sea looks white; poor visibility | |

Navigation

Wind, tide and current thus conspire to keep mariners off the deep water in the winter months, and then favour northward travel in the Irish Sea and westward travel in the North Sea (but not of course exclusively, or all the time). The ‘haven-finding arts’ have many natural signals in our region.9 The whole of Britain stands on the continental shelf, with a depth of surrounding water of less than 100 metres, with characteristic estuarine outflows of broken shell and sand that can be picked up on a plumb-line. The sun is lower at midday the further north you go, so a mark on the mast gives a crude measure of latitude. As modern coastal dwellers know, the winds feel different depending on their direction: cold and dry (from the north, a ‘northerly’), cold and wet (an easterly), warm and wet (a westerly), warm and dry (a southerly). The coastline, as viewed from the sea, has a profile that mariners learn to recognise, and early medieval people used burial mounds and standing stones as seamarks to indicate the entrance to estuaries and firths.10 It is said that the sea breaking on certain rock formations makes a characteristic sound that can be heard in fog or by listening for it on the gunnel. The edge of the continental shelf is where fish congregate, marked by a feeding frenzy when the herrings or mackerel are in: the sea is flecked with a wavy line of fish fragments and seen from a distance as a ribbon of diving birds. In the western seaways, birds are especially useful: the nightly rush of fulmars indicates the direction of land. Geese go north in spring to feed and nest, and can be seen, skein after skein, through the day and sensed by night from their reassuring yelps. Since they must eventually land, the geese lead the way from the Irish Sea to the northern isles and beyond, to St Kilda, Faeroes and Iceland. These were the escorts of the firmament that led the early Christian wanderers in leather boats to remote islands in mid-ocean.11

Types of boats

The third component of the mariners’ package was the type of boat available, owed to tradition and (some) invention. Tradition dies hard in boat building, where experience and superstition maintain a stubborn alliance.12 In the western sea, boats had been constructed since the Bronze Age (or before) from stitched leather stretched over a wickerwork frame and made watertight with butter; these were observed by Julius Caesar and still formed the template in the early middle ages as the Irish curragh and the Welsh coracle.13 They were light and so could be the more easily carried over short necks of land separating seaways, using wagons.14 These ‘portages’ cut journey times or avoided turbulent water.15 The shorter distances between landfalls and the numerous islands favoured a type of pottering itinerary from cove to cove in inshore waters.16

As seen in rock art, Bronze Age boat builders in the eastern seas also used a skin-over-frame build, possibly inspired by seeing seals and whales. Dugouts, made of a single tree trunk hollowed out, are the ancestral craft of lake and river. In the later Iron Age, small boats of about 3 m in length us...