![]()

Figure 1.1 Goblin Valley, UT

1

Introduction

This book is written for arts practitioners, arts administrators, art educators, and those interested in how the arts can contribute to strengthening cultural resiliency in the face of rapid cultural and environmental change. This work draws upon the collective experience of artists and academicians in the United States, Australia, and Greece to examine models of field programming1 tested in a wide range of social and environmental contexts.

The impetus for this work springs from a concern that the problems we humans face at this point in our history are immense and can only be surmounted by the long-term commitment of individual citizens, communities, corporations, and nations to make fundamental changes in our relationship with each other and the planet. Moving amongst academic analysis, personal interviews, and stories from first-hand experience, this text intends to chart a course for a revision in arts education in the face of a looming global ecological crisis.

The five programs and seven directors represented in our study are involved in the long game of preparing the next generation for what lies ahead. We all navigate the barriers and compromises inherent in accepting salaries from cultural institutions driven by agendas beyond our control and, at times, in opposition to our beliefs. We have turned away from the charismatic hero model so beloved in our culture to invest in the idea that the solutions lie in the power of our collective creative intelligence. We are committed to making a difference in the places in which we live by investing in the young people of our home regions and our public institutions of higher learning.

We advocate for the importance of field programming, not as a replacement for a traditional academic curriculum but as an expanded frame. Under the current administration in the United States, the fundamental value of higher education has been called into question. This text is written from the position that universities and colleges play an essential role in our societies. Our collective commitment is to public institutions of higher learning as an essential component of the cultural commons. The physical and temporal space universities continue to provide for quiet contemplation is of ever-greater value in a world operating at rapidly increasing speeds. The importance of the utopian community they create as a safe space for people of all gender, ethnic, cultural, and class identities to freely interact on an egalitarian basis cannot be overestimated in an increasingly polarized world. The efficacy of academic institutions as incubators for new ideas and technologies has been proven over and over again. Our contribution is to simultaneously expand both the physical and conceptual territory of academic institutions by adding experiential learning through engagement with environments and communities.

The programs discussed constitute a small selection from the broader practice of field programming. The focus here is on academic Fine Art programs in public institutions with which I have had direct experience in my role as director of the LAAW program. Excellent work in field programming is being done by other Fine Art programs, such as the Art and Rural Environments Field School at UC Boulder and in other disciplines within academic programs, such as Land Works in the Department of Architecture, Design, and Urbanism of Alghero (UNISS) and Land Arts of the American West in architecture at Texas Tech University.

A separate group of field programs operating outside of academic structures includes programs such as Signal Fire, Cape Farewell, The Field School Project, Unknown Fields, The Arctic Circle, and Artemis Institute. These programs, both academic and independent, share with our cohort a nomadic operating methodology that differentiates them from the even larger group of location-based residency programs, such as A-Z West, Broken Hill Art Exchange, M12, Mildred’s Lane, and US National Parks Airs to name a few.

The conceptual territory occupied by our cohort of field programs ranges from environmental art to interdisciplinary collaboration and social practice. The issues that have arisen in our investigations touch on major cultural themes globally. Specific topics are being rigorously explored at present by an ever-expanding list of individuals, groups, and organizations. Of particular relevance to this discussion is the work currently undertaken by collaboratives and collectives around the globe. In our investigations of the possibilities for interdisciplinary work amongst teams of artists and scientists, we look to Cape Farewell and The Arctic Circle as highly successful examples. Unknown Fields Division takes a global approach to their explorations of contemporary environmental and social issues, while Platform London’s projects address social and environmental justice from their base in the United Kingdom. The Danish group Superflex focuses its activities on energy and economic issues. In France and Thailand respectively, la r.O.n.c.e. and The Land have created contemporary utopian agrarian communities. In the United States, the Center for Land Use Interpretation has been greatly influential in expanding the frame and focus of our understanding of artistic practice. In the emergent realm of social practice, groups like Black Lunch Table are leading the way. Metabolic Studio addresses the issue of environmental sustainability in the urban center, while Simparch is doing important work in sustainability in the nether regions of the American West. Our explorations of arts activism have been informed by a wide-ranging group, each with its own particular approach. Future Farmers has been a pioneer in exploring the possibilities for comingling sculpture, design, and performance in community actions. Highlander Folk School has a long history of combining crafts, music, and activism in Appalachia. Critical Art Ensemble brings their activist form of performance to an international set of issues. The Laboratory of Insurrectionary Imagination, Labofii, consists of “an affinity of friends who recognize the beauty of collective creative disobedience”,2 while Post Commodity adds a focus on Indigenous political activism to their community engagements.

This is merely a partial list of collectives and collaborative groups that is offered here as evidence of the depth and breadth of these emergent practices in the arts. We have learned from all these groups, and the work of individual artists as well, and have drawn upon their examples in refining our pedagogies. Our focus in this text is on five programs operating within academic institutional structures with a focus on interdisciplinary, ecological, community-based arts education. In the following chapters, we explore the initial conditions that engendered the individual programs, the pedagogies created, the logistic systems developed, and the results experienced by the contributing authors.

The Land Arts of the American West (LAAW) program at the University of New Mexico (UNM) serves as the primary case study. The other programs presented include Field Studies (FS) and Balawan Elective (BE) at Australia National University (ANU), Landmarks of Art (LMoA) at Mira Costa College (MCC), Place Appalachia (PA) at West Virginia University (WVU), Art and Environment (A&E) at Colorado State University, Fort Collins, and The Visual March to Prespes (VTMP) at Western Macedonia University (WMU).

These programs are connected by a series of direct programmatic links forming an international community of field programs in the arts. Erika Osborne and Yoshi Hayashi are LAAW alumni who have gone on to create their own field-based programs in the United States – at West Virginia University and Colorado State University (Osborne) and at Mira Costa Community College (Hayashi). John Reid has directed his field studies program at Australia National University in Canberra, Australia, since 1996, and Yannis Ziogas has led the March to Prespes program at Western Macedonia University in Florina, Hellas, since 2007. Jeanette Hart-Mann has succeeded Bill Gilbert as director of the LAAW program; Erika Osborne has moved to Colorado State University Fort Collins, where she has started the Art and Environment (A&E) course; and Amanda Stuart has continued the FS tradition John Reid started at ANU by forming the Balawan Elective (BE) field course.

A significant aspect of this study is the degree of active interaction amongst the programs. Collaborations amongst the programs have occurred in several forms over an extended period. In 2009, LAAW alumni Cynthia Brinich- Langlois, Blake Gibson, Yoshimi Hayashi, Joseph Mougel, and Cedra Wood accompanied Bill Gilbert on a month-long project with John Reid and FS at the Sinaloa Research Station and Jigamy Reserve in New South Wales and Calperum Station in South Australia. In 2011, John Reid and Marzena Wasikowska joined the LAAW program in the field for our investigation of the US–Mexico border in southern New Mexico and Arizona. John Reid’s assistants in FS, Amanda Stuart, Heike Qualitz, and Amelia Zaraftis, participated in the LAAW program in 2012 and 2013. Exhibitions featuring the work of FS, LMoA, PA, and LAAW faculty and students were presented in the United States and Australia in 2011, 2013, and 2014.3 Yannis Ziogas, Erika Osborne, and Bill Gilbert collaborated on the Exit Cities project for the International Visual Sociology Conference in Brooklyn in 2012. The LAAW and VMP programs collaborated on field projects related to our shared interests in national border zones in 2012 and 2013. This work was presented in an exhibition in Greece in 2012 and a related book in 2015.4

The list goes on. The salient point being that while these programs were created independently, they have evolved as part of a shared community. The cross fertilization has informed the development of the individual programs, and our students have benefited from the networks created. The shared collaborations amongst these groups have revealed similarities and distinctions in the programs’ social and environmental contexts. Going forward in this text, we will discuss the particularities of each program while investigating the common issues that translate across the three hemispheres in the effort to provide the specific information necessary to form and operate a field program. We intend to build a case for field programming in the arts as a significant component of contemporary arts pedagogy that is worthy of institutional support globally.

Notes

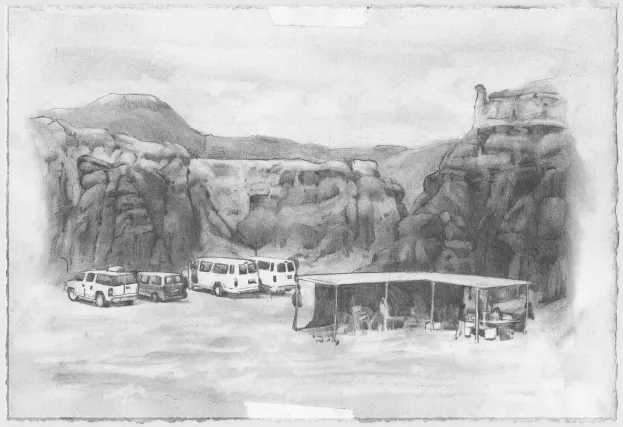

![]()

Figure 2.1 America’s Big, Jonathan, “Dirty Monke”, Loth and Gabe, “Bunny Krunk”, Romero, North Rim Grand Canyon, AZ

2

A place to stand

The rationale for field programming

This book makes a case for field programming as an important component of a contemporary academic curriculum and provides the collective experience of field programs on three continents as a guide for those wishing to implement new programs of their own. While the focus is on academic programs, the basic concerns of social and environmental sustainability are societal in scope, making our emphasis on engagement transferable to other contexts.

The LAAW and FS field programs began in the late 1990s as the United States marked the height of a decade-long economic boom. In the United States, the dotcom bust was just around the corner, but as LAAW launched at UNM, we were in a mind-set of growth and possibility. At that point in time, the environmental movement was pushing the warnings of Silent Spring1 and The Population Bomb,2 but the potential effects of climate change were not part of the mainstream cultural dialogue. Race relations and immigration issues simmered below the surface of other societal concerns. In the intervening decade and a half, we have experienced terrorism, endless wars, a major economic interruption, severely increased polarization of our society, and an ever-growing awareness of the possibility for human-induced ecological collapse.

As nations around the globe struggle with the difficult issues of dislocation, migration, environmental degradation, economic inequality, and racism, the arts have an important leadership role to play in the cultural dialogue. The long-term commitment in western societies to the primacy of science has resulted in the availability of a vast resource of data regarding these issues. Our fascination with technology has produced the Internet, and, as a result, our populations now have unprecedented access to vast troves of information. And yet, we can’t seem to synthesize this information and act. There is now a pervasive awareness that humans have altered the planet in such significant ways over a sufficiently extended period of time that we have entered a human-driven geologic epoch entitled the Anthropocene in which there will be major disruptions for all species, including humans. These environmental disruptions will only exacerbate the current mass dislocations and resulting migrations of human populations that will in turn cause increased stress and strife amongst cultural groups. The concepts of the “Sixth Extinction”3 and “Deep Ecology”4 have entered the cultural discourse. We logically know the import of all of this, and yet, we can’t manage to make changes in our behaviors.

The United Nations Agenda 21 makes a clear case that education will have to be an essential contributor if we are to return the ecosystem of planet earth to a sustainable balance.5 For those of us involved in this sector, the advent of the Anthropocene requires a rethinking of our approach. To teach art as a discreet discipline involved in a close...