- 568 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

This book provides an illuminating introduction to a collection of readings on social theory and provides an overview of the socio-historical context and delineation of key thinkers and texts. It includes a new section exploring social theory at the limits of the social.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Social Theory by Charles Lemert in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Social Sciences & Sociology. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

PART ONE

Modernity’s Classical Age: 1848–1919

A work of literature is considered a “classic” when, long after it was written, readers continue to read it. A famous example is Sophocles’s dramatic telling of the story of Oedipus. This is so much a classic that one does not need to have read Sophocles, Shakespeare’s Hamlet, or Freud to know something of the story. Most people recognize in themselves the truth told in this ancient Greek drama: that human beings are affected deeply by extreme feelings of love and hate for their parents.

In most versions of the story, Oedipus loves his mother too much. Without knowing what he is doing or who the people involved really are, Oedipus kills his father and marries his mother. He rules his land with Jocasta, his mother-wife and queen. When a plague threatens the kingdom, Oedipus learns that his land can be saved only if his father’s murder is avenged—and that he himself is the murderer! He blinds himself and goes into exile. Oedipus’s actual blindness represents his deeper blindness to the effects of his desires on his behavior. His fate is tragically determined not because he had forbidden feelings of love and aggression for his parents but because he acted on them without knowing what he was doing. This story is a classic because people find in it some sort of standard for normal, if confusing, human experience. In literature, a writing is classic because it still serves as a useful reference or meaningful model for stories people tell of their own lives.

Hence, a period of historical time is considered classical because people still refer back to it in order to say things about what is going on today. Generally speaking, classical ages contain a greater number of classical writings for the obvious reason that literatures express their social times. Thus, at present, when people refer to the Oedipus story, they usually have in mind Freud’s version, which still conveys much of the drama of the modern world affecting people today. The Oedipus story figured prominently in one of Freud’s classic writings, The Interpretation of Dreams, which was published in 1899. In this book, Freud made one of his most fundamental claims about dreams just after retelling the Oedipus story. Dreams, he explained, are always distorted stories of what the dreamer really wishes or feels. They can thus serve “to prevent the generation of anxiety or other forms of distressing affect.”

Freud’s telling of the Oedipus myth is a subject of controversy today because it is taken as a case in point for the feminist criticism that most classical writings in the social and human sciences systematically excluded and distorted women’s reality. They did. In this case, Freud distorted reality by his preposterous inference from the Oedipus he saw in his patients to the claim that the major drama of early life is the little boy’s desire to make love to his mother. Little girls were left out of this story, the crucial formative drama of early life. They were said to be driven by the trivial desire of envy for the visible instrument of true human development, the boys’ penis. The feminist critique is to the point, but it does not destroy the classic status of Freud’s writings. Feminists are among those who still find much else of interest in his ideas.

Freud’s version of Oedipus also tells the deeper story of human blindness, of the natural tendency of most human beings to resist the full truth of their lives—to deny many deep feelings of love and hate that govern them and the world. Freud’s Oedipus remains a classic today because, among other reasons, people still find in it two basic truths of their lives: (1) They have very mixed and strong feelings about the people around them, and (2) therefore, they tend to distort what they say and think about the world because what they feel below the surface is far too upsetting. People are blind to their own feelings because their worlds are too much to feel.

Social Theory’s Classical Age: Confusion and Doubt in a Changing World

This would also be a reasonably good description of what many bourgeois Europeans at the turn of the century were feeling (but not saying) about the modern world in which they lived. They said it was a wonderful thing, filled with hope. They felt, but resisted saying, that the modern world did a lot of harm and made them feel less than hopeful about the human condition. In other words, Freud told of Oedipus to help tell the story of dreams, which in turn helped tell the larger story of the late modern culture in which many people wanted to believe anything but the complicated reality of their worlds. Carl Schorske, in Fin-de-siècle Vienna (1961), explained that in his theory of dreams, “Freud gave his fellow liberals an ahistorical theory of man and society that could make bearable a political world spun out of orbit and beyond control.”

This, it turns out, is a good description of the modern world in the period from the revolutions of 1848 through at least the end of World War I. Contemporaries of those who visited Freud for psychoanalytic consultation in Vienna at the end of the nineteenth century were the children or grandchildren of people whose roots were in the traditional world. People who lived in a major city like Vienna may have enjoyed much of its cultural, political, and economic abundance. But it would be hard to believe that they did not also regret what was lost in these new cities. The political revolutions in America and France at the end of the previous century promised a new and better world, as did the dramatic economic revolution that was then spreading from England across modern Europe. Democracy in politics, capitalism in the marketplace, and science in culture offered much. On the surface, everything was expected to be better. For many it was.

For many more, and even for those whose material lives were better than anything their parents ever knew, life was filled with anxiety. For one thing, the modern world brought destruction. Throughout the century, lands were taken to build the railroads that fueled the factory system. In America, native civilizations were destroyed in the name of progress. Someone must have given this a second thought. If not, people surely saw what was happening closer to home. After 1853, Baron Georges Haussmann, often called the first city planner, ordered the destruction of much of old Paris to build the new boulevards and monuments that today’s tourists mistakenly associate with tradition. The boulevards were allegedly built to allow a straight cannon shot into the working-class quarters, where rebellions like those in 1848 were most likely to recur. In Chicago in 1871, the great fire destroyed much of the city. The fire provided occasion for the rebuilding of Chicago as a modern city. Architectural historians claim that engineering advances necessary to construct the skyscraper were developed in order to rebuild Chicago vertically. Even today, everyone who lives in a city knows that modern “progress” entails the tearing down of much that is traditional. The skyscraper became the strong symbol of modern urban power, typically built on the site of perfectly good lands and homes. What met the eye in the cities was just the surface representation of what so many people felt about the modern world. In a different political sense, many still contend that the modern world destroys the old family and small-town values, as indeed it does.

Modernity could be defined as that culture in which people are promised a better life—one day. Until then, they are expected to tolerate contradictory lives in which the benefits of modernity are not much greater than its losses, if that. In Marx’s famous line, the modern world was one in which “all that is solid melts into air”—nothing was quite what it appeared to be. No future payoff was ever quite assured for the vast majority of people. The first sign of the coming good society was always, it seemed, the destruction or loss of something familiar and dear. Many people in Europe and North America in the second half of the nineteenth century lived in an oedipal state, as Freud described it: affected by strong feelings of love and anger for their world but unable to give voice to the anger for fear of “saying the wrong thing.” They were expected to love a world that was killing what was dear to them.

These were the cultural conditions prevailing in the modern West from 1848 into the first quarter of the twentieth century. This was the classic age of modernity, and of social theory. Whether practical or professional, social theory became a more acutely necessary skill in this period. Practically, ordinary people, many of them new to the strange and alien city, needed to learn to introduce and explain themselves to strangers who knew nothing of their family names. Professionally, there arose for the first time a class of writers, lecturers, teachers, and public intellectuals who devoted themselves to telling, in scientific language, the story of the modern West. Among them were the classic writers of modernity’s classic age.

Classic Social Theories Struggle with the Contradictions of the Modern

Karl Marx, Èmile Durkheim, Max Weber, Georg Simmel, Sigmund Freud, and others are still considered classic writers because they told the story of modernity with a subtle regard for its two sides—for the official story of progress and the good society and for the repressed story of destruction, loss, and the terror of life without meaningful traditions. Their value to present-day readers is partly evident in the very fact that they are still read. This separates them from others: those great writers of the nineteenth century who are no longer read seriously lacked the subtle grasp of both sides of the modern world. Auguste Comte is often considered to be a founding father of sociology, along with his mentor Saint-Simon. But few would read his works today in order to understand the modern world. Comte was too blind to the other side of that world. He believed too much in its progress and thus could say, in 1822: “A social system is in its decline, a new system arrived at maturity and approaching its completion—such is the fundamental character that the general progress of civilization has assigned to the present epoch.” Simple, all too simple. Much the same can be said of the sociologist who has become for many the perfect illustration of the fallen classical god. Herbert Spencer, a more sober and scientific man than Comte, saw the world as progressing slowly but perfectly toward good and thus could say, in 1857: “Progress is not an accident, not a thing within human control, but a beneficent necessity.”

Delicate is the line separating those no longer read and those who are. The difference is not so much in the ideas themselves as in the finer sensibilities with which certain nineteenth-century social theorists let on that they knew the world was complicated, while others did not. Èmile Durkheim, heir apparent to Comte’s faith in modern science, let it be known that scientific sociology was urgently needed not just because progress was at hand but also because the lawlessness of modern society had devastating effects on the weaker, more marginal individuals. And each of the writers who are still read wrote of concepts that described the dark side of modern life—Durkheim’s anomie, Marx’s alienation (or estrangement), Weber’s overrationalization. Even Freud, who was not considered a social theorist until recently, hardly makes sense outside the social world for which he wrote. How else are we to interpret his compelling sense of psychological life as a wild disturbance in the hostile conflict between deep, natural desires to love and kill and the prudish, censorious forces of bourgeois manners? As much as Marx and Weber, Freud described the hidden irrational forces of social life. More perhaps than they, he described how the irrational is a given in the order of human things found just below the tranquil surface of reason.

Then too among the classical social theorists, Marx in particular set his theory of political economy against the classical political economists—Adam Smith, Thomas Malthus, and David Ricardo. But Marx was not alone in seeking a more robust idea of social forces in relation to the autonomous individual. Durkheim and Weber, even Freud, along with Marx, proposed theories that served to challenge the all-but-absolutely free individual of classic economics. Modern man was to them socially determined (Durkheim and Marx), or caught in a web of social ambiguities (Weber), or irrationally driven by primordial unconscious forces (Freud). Yet, as time went by, John Stuart Mill, a theoretical heir of the classic economists, wrote in On Liberty (1859) of the individual in a way that took seriously the social fact that individual freedoms are socially embedded. Not long after Mill, a philosopher of quite a different temperament wrote devastatingly of European culture and its philosophies. Friedrich Nietzsche, whose appreciation for the negative side of modern society is said by some to have influenced Weber and Freud, was also able to write in Beyond Good and Evil (1886) with sociological sensitivity of the practical nature of social relations.

These classic writers in a classical age are considered worthwhile because people continue to struggle with the confusing effects of modern life. There are some who would say, a century after social theory’s classical age, that the modern world is coming to an end. This could be. But what remains true is that a great many people still find hard reality at moral odds with the promise of progress. Those who have no experience of this contradiction would not find these classic writers interesting, just as anyone who denies his or her experience of the deeper emotional forces would find Freud’s Oedipus opaque.

It must be said, however, that a work can be considered classical for reasons other than the continuing appeal of its wisdom. Classics serve less lofty social purposes as well. The process of canon formation is well understood today to be part of the social process whereby those in power (or some of those with some power) seek to perpetuate the authority of certain authors in order to enhance their own vested interests in a given view of social life.

The first condition of being read is to be published. Because publication involves commercial as well as literary judgments, decisions to publish are always and necessarily susceptible to the influence of editors, publishers, advisers, and critics whose interest in what is read is touched by an interest in the economics of literary and cultural life. Great works of literature can be excluded from an official canon for many reasons having nothing at all to do with their merit. Publishers think they won’t sell. Editors think they serve no good purpose. Critics cannot understand why anyone would buy and read something by one of those people. Authors don’t even try because they know what publishers will say. This is neither good nor bad. It is, however, a fact of cultural life that a literary work of great merit can be denied the status of a classic because it is excluded from the canon; conversely, a work can appear in the official canon of great writings even though it has little or no merit.

A writing that endures over time always encounters these two forces: to be classic, it must be readable to readers; to be a canonized classic, it must serve the interests of those who decide what readers will read. Great books like W. E. B. Du Bois’s The Souls of Black Folk (1903) were virtually unknown to the dominant, mostly white, literary establishment until recently. Other books, like Èmile Durkheim’s Rules of Sociological Method (1895), have been canonized even though no one reads them. Herein lies a particularly interesting story. Durkheim’s Rules is a book that made little or no sense, not even to Durkheim. When he tried to demonstrate his rules in his study of suicide, he was unable to make them work. Yet the young Durkheim wrote the book specifically so that it might one day be a classic. Rules began with a familiar locution: “Up to now sociologists have scarcely occupied themselves with the task of characterizing and defining the method they apply to the study of social facts” (my emphasis). He then proceeded to attack the most widely known textbook on sociology, which just happened to have been Spencer’s Study of Sociology (1873). Durkheim thus used a familiar prophetic device—“Up to now … / but, verily, I say unto you”—to establish his little book as a classic. He was seeking a definite canonical market position. Today, as in his day, there are those who like the idea of keeping Durkheim’s book on methods in the canon, so they assign it, students buy it, publishers print it. But does anyone read it? If so, can anyone honestly make sense of it? Has anyone ever actually used those rules? Not likely.

A classic must interest readers, whether or not it is in the official canon of classic works. Conversely, canonical status does not automatically make a book a classic. This awkward relation between the classical and canonical statuses of a writing is somewhat accidental and, in retrospect, of surprising importance to social theory. Today, it is well understood that a great number of social theories written during the classic age were, directly or indirectly, excluded from the list of officially approved great works. They were, therefore, denied the public availability that would have caused them to be read as classics. Until now.

In addition to such powerful works as The Souls of Black Folk (1903), Charlotte Perkins Gilman’s “The Yellow Wallpaper” (1892), and Anna Julia Cooper’s Voice from the South (1892), there are thousands of essays, novels, and narratives by women, freed slaves, workers, Native Americans, and others denied privilege of place in the public culture of their times. The discovery of these writings has encouraged a rethinking not only of some of the official classics of the modern era but also of the historical period itself. Once again, in a different way, the literature reveals the times. First in importance among the earliest of feminist writers was Harriet Martineau who, as early as 1837 in the short essay “Woman” wrote boldly and persuasively of the “injuries suffered by women at the hands of those who hold the power.”

If Marx, Weber, Durkheim, and Freud sketched theories of the contradictory nature of the modern world in the late nineteenth century, then these theories are painted in bolder, more passionate tones in the newly discovered classic texts. Du Bois wrote of the double-consciousness of American Blacks forced to live beyond the veil of racial degradations. Gilman’s “The Yellow Wallpaper” similarly described a woman’s double-consciousness—expected (and desiring) to please the men who would heal her, knowing the irrationality of their condescending reasonableness. Cooper gave voice to the Black women in the South who knew (and know) that they must be doubly or multiply conscious of the good men of their own race and of the good whites of their own gender. These were the experiences of people cruelly oppressed b...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Dedication

- Table of Contents

- Preface/2016 Edition

- Acknowledgments

- INTRODUCTION Social Theory: Its Uses and Pleasures

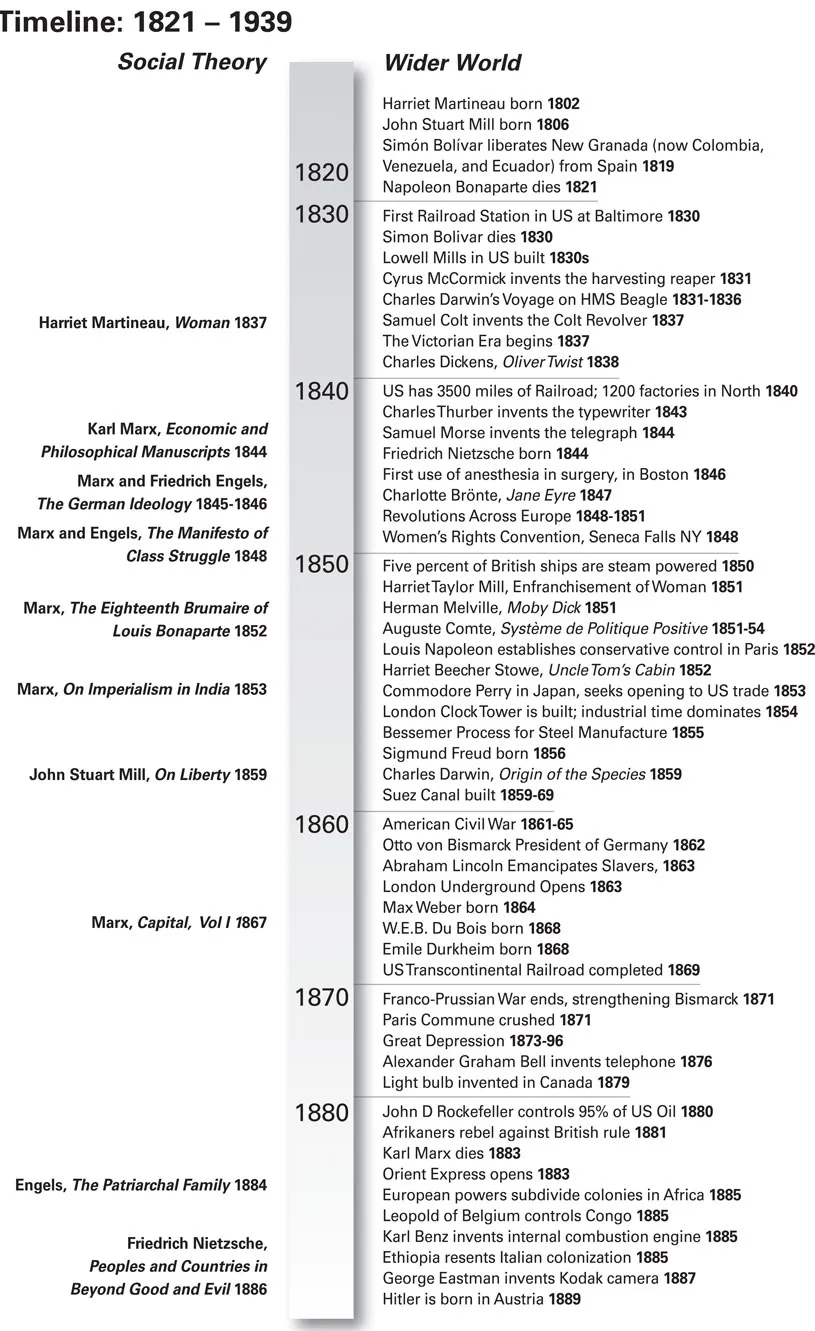

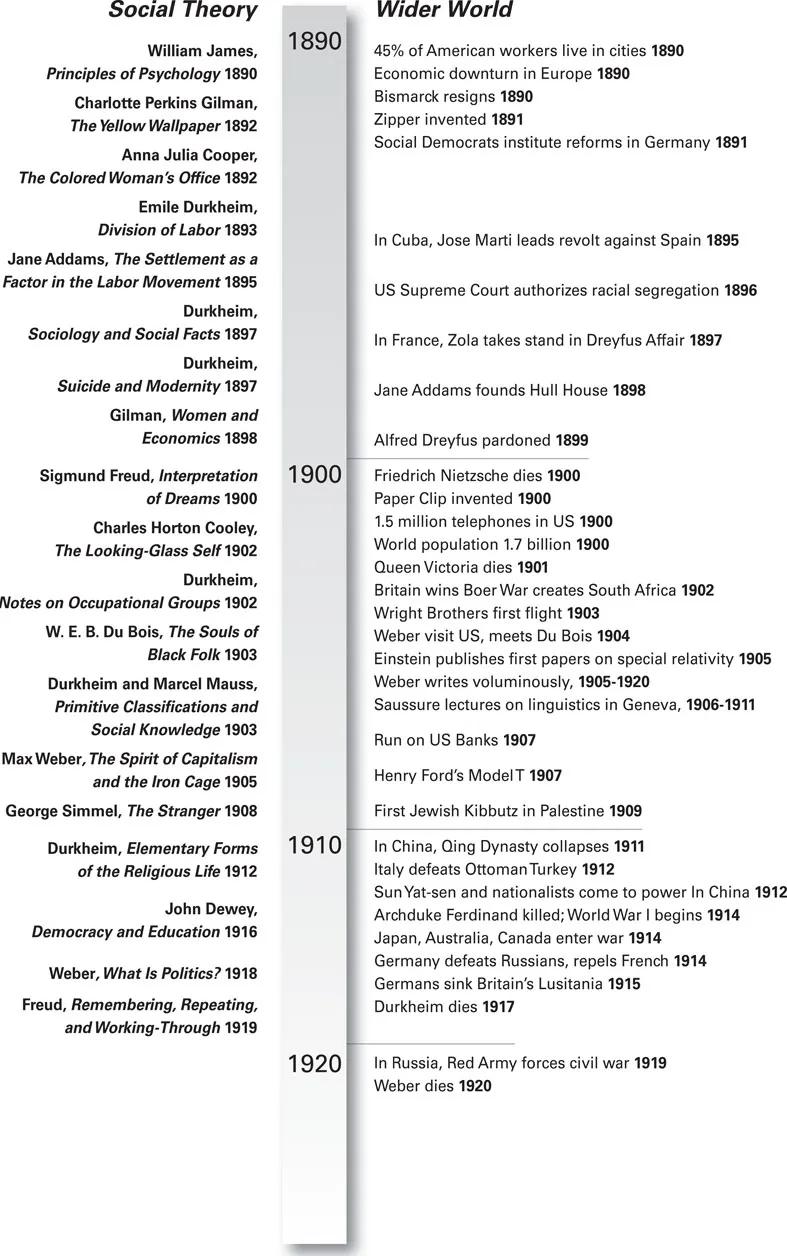

- PART ONE Modernity’s Classical Age: 1848–1919

- PART TWO Social Theories and World Conflict: 1919–1945

- PART THREE The Golden Moment: 1945–1963

- PART FOUR Will the Center Hold? 1963–1979

- PART FIVE After Modernity: 1979–2001

- PART SIX Global Realities in an Uncertain Future

- Name Index