- 352 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Language And Communicative Practices

About this book

This book focuses on major theories of language from several disciplines and aims to develop an approach to communicative practice that combines the formal properties of linguistic systems with the dynamics of speech as social activity.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

Chapter 1

Introduction: Meaning and Matters of Context

START WITH A SIMPLE SCENARIO. It is 7:28 a.m. on September 19, 1993. Chicago. Jack has just walked into the kitchen. He is standing at the counter by the sink, pouring a cup of coffee. Natalia is wiping off the dining room table. Gazing vacantly at his coffee cup, still drowsy, Jack says,

“D’the paper come today, sweetheart?”

She says,

“It’s right on the table.”

Turning to the small table inside the kitchen, he picks up the paper and his cup of coffee. He joins her out in the dining room, where they sit in affectionate silence. She scribbles a list of the day’s chores: “Review headlines in Trib, Times, Globe, Post in re: UN role in peacekeeping efforts; prepare handout for PoliSci seminar; call AMH re: Friday; gym at 2:00; renew books at lib; dentist 4:15.” Unfocused, his eyes wander over the headlines: “The Moment of Truth,” “Duke Learns of Pitfalls in Promise of Hiring More Black Professors,” “In a Less Arid Russia, Jewish Life Flowers Again (A Faith Reviving. Jews in Russia. A Special Report),” “Perot, at Rally, Upsets Members of Both Parties.” They kiss. He lowers his face, rests it on the nape of her neck. After a moment, he turns back to the paper, still vague with sleep. She returns to her list. He sips his coffee, thinking of the day ahead.

In itself, language is neither the cause nor the measure of the world as we live it. Much of what makes the headlines would happen without talk, and we are instinctively wary of words for their ability to deceive. The dining room would still be there, and Jack and Natalia could still take their coffee, by habit, at the table. He would undoubtedly have found the paper on the table even if he never asked, and she could have just pointed. Virtually asleep, his words express little that we would call meaningful, and his eyes glaze over the paper, barely focusing on the information it announces. They embrace in the silence of intimacy. In other words, the consequential features of the scenario don’t really depend upon the words spoken or even the speaking of words. The telegraphic exchanges between intimates can be virtually predictable or so idiosyncratic as to lack general interest. We need not even assume that they are wide awake. Next to disease, the environment, racism, and terror, speech seems oddly weightless. Talk is cheap.

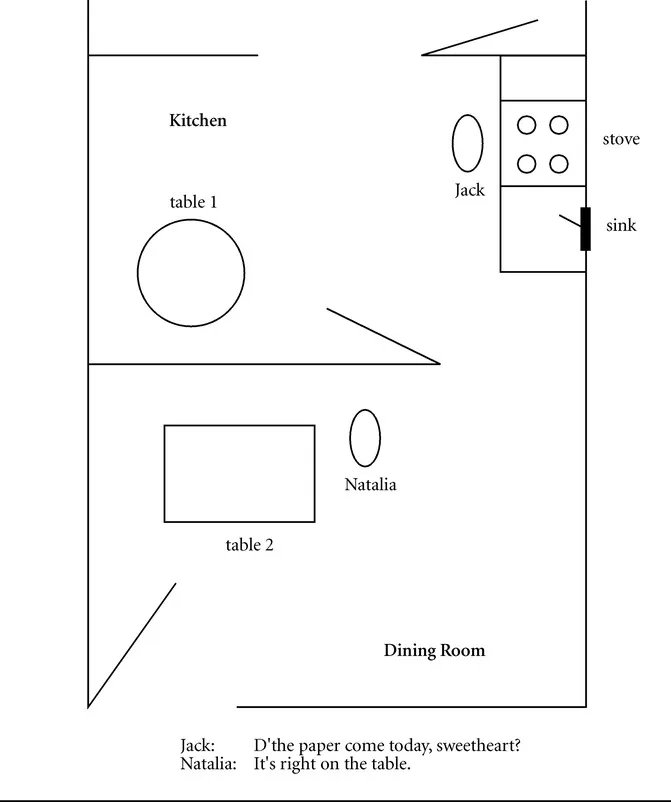

FIGURE 1.1 Floorplan for a Routine Exchange.

True enough. But language permeates our daily lives, from the kitchen to the UN, and all the media in between. This sheer commonality should give us pause. The news might still happen without speech, but it would be difficult to call it news if it were never reported, and this happens only through language and other symbolic media. Jack and Natalia—or any other couple, for that matter—can do many things in silence, but this does not cut them loose from the horizon of words. There is always a history of conversation, intimate tellings. There are moments of withdrawal, when language is present by its painful absence. Common sense tells us that speech involves sound, but language inhabits silence, too (for the same reason that people are social beings even when they are alone). The truth has its moments because a pledge has been made. A university finds its present measured by a promise in the past. A third-party candidate breaks in with speech. And of course the newspaper is a printed form of language, whatever else it is. Sitting in the dining room in silence, Jack and Natalia are embedded in an unseen dialogue.

The notion that talk is trivial compared to real action is often paired with the assumption that the meanings of words and utterances are transparent. We feel confident glossing Jack’s utterance as a request for information about the paper or perhaps for the paper itself. Natalia s response appears equally simple and virtually literal. A closer look at their words, however, suffices to muddle this picture. Jack’s question only asks whether the paper came that day, which should merit a simple yes or no response. Knowing that he reads the paper with breakfast and that he has no independent interest in newspaper delivery, Natalia hears his question as a request to locate the paper for him at that moment. It is this unspoken utterance that she answers. Her answer in turn introduces further tacit knowledge. Notice in Figure 1.1 that there are two tables on the scene, not one. The tables are in different rooms, as are the two people. Yet Jack hears her statement as making reference to the one nearest him, the one farthest from her. She cannot even see the table in the kitchen, and he knows this without having to think of it. How does he understand her? One might reason that he would expect her to say, “It’s in here,” or some such, if the paper were already on the dining room table. That she does not say this becomes meaningful. The assertive tone of her statement further reinforces the inference that she is giving him just the information he needs to find the paper. Maybe the words “right on the table” convey that it is close to Jack, that he should be able to see it clearly.

But which inferences are actually made by such people, half asleep, in the familiar surround of their own home? Neither of them specifies that it was the newspaper of September 19 that Jack wants and not, say, the one from the day before. Yet this is implied, too. If the paper routinely came a day or a week late, then Natalia would understand him to be asking about that edition of the paper, and not the one of September 19. Papers can’t move around by themselves anyway, so why does he ask if the paper “came” instead of asking if it was delivered? Moreover, although he never says so, Jack is obviously referring to a certain newspaper and not the wax paper, the toilet paper, or the computer paper, and his use of the word “today” suggests that there are some days on which it doesn’t come (and therefore others on which it does). This gives the entire scenario an air of routine.

It should be clear that simple exchanges like this one can be tinkered with indefinitely and that much of the transparency that we sense on first hearing can be made opaque. The very telegraphic quality of the exchange, the presence of all that is unsaid, is part of what makes it appear routine. And we, as native actors, are curiously comfortable amidst an infinity of assumptions, beneath a horizon as familiar and unnoticed as the night sky. That is, provided we have the right kinds of background. Provided, for this example, that we come from a world in which people have dining rooms and read newspapers, in which men and women act as couples in certain common ways, in which English is spoken and coffee is drunk in cups in the morning. All of these things could be different, yet the coherence of words among silence would be similar—until something happens to break up the pieces, and the meanings shift about.

FIGURE 1.2 Morning Headlines

If the same exchange took place in a commercial kitchen in which large quantities of wax paper were needed, and Jack and Natalia were coworkers, he the short-order chef and she the manager, then it might be the wax paper that he was wondering about, taking for granted a history of problems with the supplier. Or Natalia might be the one who uses the paper because she works in the kitchen, and so Jack, the bartender, asks a real question whether the paper was delivered and not a request for information about its current whereabouts. What if Natalia, a native Spanish speaker, is actually practicing her English and the entire dialogue is a pedagogical exercise? Or if they are acting on the stage or running over an exchange they plan to perform at a later date in front of some third party, for reasons undisclosed? Back in the dining room, Natalia might know that Jack really wanted the newspaper, but she remembers that she happened to leave a new roll of toilet paper on the table when they returned from shopping the night before, and she playfully sends him to it, twisting his words mischievously. And so on. As we change the setting, making different assumptions, the meanings of the words shift around, become opaque, or change entirely.

The same applies to the boundary between language and gesture in much of everyday talk. Meanings understood without reflection turn out to depend in intricate ways on the cooperation of body posture and motion with speech. Jack’s grasp of which table Natalia means is based on his body sense of her physical location outside the built space of the kitchen, relative to his own inside it. He is standing, about to walk to the dining room, and so can easily turn and pick up the paper as he comes to her. The two tables are in turn anchored to this relation and the habitual motion through the doorway between the two rooms. They sit close enough so that their embrace can happen as if by itself, without comment or preparation. Like the other tacit features of the scenario, most of this is so banal that a reader can digest the example easily. It takes a special effort and a certain perversity to make it strange. It takes a certain remove to unstick the words from their context, bringing their specific form into the foreground.

The goal of this book is to develop a perspective on language and speech, to ask how meaning happens through speech and silence, bodies and minds. The field is what has come to be called linguistic anthropology, although I will attempt neither a review nor a history. My method includes taking simple examples and showing the ways in which they depend on social context and some of the ways this dependency has been thought about. The purpose of questioning the obvious is not just to muddle things but to induce certain logical breaks. The first of these involves alienating our notion of language from the deceiving concreteness of common sense. In the commonsense perspective, we usually “hear through” the words people speak and “see through” their gestures, to seize directly on a larger meaning. This tendency to hear through is the first thing we must suspend in order to rediscover what gets said when people speak. In a sense, we have to unlearn some of the skills that make it possible for us to interact or read things like the newspaper.

We will inevitably continue to trade on common sense throughout such an exercise. There is no other alternative. But the point is to make this part of the problem by examining the relation between what is actually said and what is understood. It is more a matter of bracketing, or temporarily suspending, contextual inferences rather than rejecting them outright. This first break, then, is what will allow us to separate the speech form from its own commonsense horizons, which in turn allows us to hear the words within the speech—which is in turn the first step toward language as a pure form with an inner logic of its own. “D’the paper come today, sweetheart?” Yes-no question; past tense verb of motion with singular, inanimate subject; inverted word order of auxiliary verb and subject noun phrase; temporal adverb referring to the day of the utterance; utterance-final vocative, [+ familiar]; primary stress on first syllable of “pépr”; intonation peak on primary stress and final syllable of “t∂déy.” This is the path of formalism, and that is why formalist understanding often runs counter to common sense.

To talk of an inner logic is to say that language is irreducible, that its structure and evolution cannot be explained by appeals to nonlinguistic behavior, to emotion, desire, psychology, rationality, strategy, social structure, or indeed any other phenomenon outside the linguistic fact itself. We can pile on as many contingent facts of contexts as we wish, but language the code remains relatively autonomous. We associate this idea with such names as Ferdinand de Saussure, Leonard Bloomfield, Noam Chomsky, and Roman Jakobson, among the founders of modern linguistics, but its reach goes far beyond a single field. For ease of reference, we can call this the irreducibility thesis. It says simply that verbal systems have their own properties, and it fits well with a number of widely known facts: Languages are pervasively systematic in the sense of exhibiting patterned regularity across time and space. Sentences can be extracted from the ephemera of utterances, and languages are more than the accidents of speech. They have universal features such that regardless of the differences between any two anywhere in the world, one can predict that they share certain traits and exclude certain others. A verbal form, such as the sentence “It’s right on the table,” can be repeated a dozen times by speakers in as many different accents and for as many distinct purposes, and yet it is still recognizable and somehow the same. Jack could describe the table before him in great detail and you could photograph it without special effects; a comparison with the object itself would reveal that the verbal description employs things like nouns, definite articles, and verbs that have only tenuous analogues in the photo and none really in the physical thing.

Languages rest for their meaningfulness on a special sort of arbitrariness that is of a piece with irreducibility. In French one calls it la table, in German der Tisch, and in Spanish la mesa, yet these verbal differences appear to correlate with no differences in the thing itself, indeed no differences other than the ones we summarize in the names of the languages. Irreducibility is a grand way of saying what any working linguist or language learner already knows, namely, that languages have grammar and grammar has its own properties. The thresholds between grammar and utterance, expressions and things, may be difficult to draw, but this does not mean that they cannot be defined precisely. Moreover, the same common sense that obscures the line by making it invisible also affirms it. We know that words have relatively stable meanings fit for the dictionary, that they can be repeated, that a text can be separated from the situation in which it is read aloud, that a language can be written without being spoken, that it can be learned, to a degree, without being lived. The first break arises from the effort to make explicit this partial independence of language as a system.

There is a second break that will concern us throughout this essay. If verbal forms are patterned, abstractable, universal, repeatable, and arbitrary, in brief sui generis, all the opposites also hold with equal force. They are variable, locally adapted, saturated by context, never quite the same, and constantly adjusting to the world beyond their own limits. And there is always an ideological dimension: people have ideas about their language, its value, meanings, history, and these ideas help shape the language itself. Here we come to the inverse thesis, which I call relationality. It is actually a family of approaches that have in common a focus on the cross-linkages between language and context and a commitment to encompass language within them. Irreducibility is of course built on a logic of relations, too, as we will see in Part 1 of this book. But the critical difference is that formalisms based on the irreducible system of language always posit a boundary between relations inside the system and relations between the system and the world outside of it. The former include things like the syntax or phonology of a language, and the latter things like the psychology or sociology of talk. Knowledge of a language, under this view, is inherently distinct from knowledge of the world. It is the idea of a boundary between language and nonlanguage that makes all these other divisions possible. The system is at once more abstract, more general, and inherently longer lasting than any of the activities in which it is put to use. Proceeding from the break with particularity, formalist understanding leads to general laws of language and models of the combinatory potential of linguistic systems. This potential logically precedes any actual manifestation of speech. Relational understanding, on the contrary, proceeds from the break with formalist generality and leads back into particularity. It foregrounds the actual forms of talk under historically specific circumstances: not what could be said under all imaginable conditions but what is said under given ones. Here we come into contact with an endless array of particulars, with momentary circumstances and their contingencies. Language appears as a historical nexus of human relationships, a sudden patchwork that defies our ability to generalize. The line between knowing a language and knowing the world comes into question. It is unsurprising that social sciences in recent decades have seen a return to historical specificity, partly in reaction to the universalizing sweep of structuralist thought. Formalism loses in verisimilitude what it gains in internal rigor. Yet the really hard part is to achieve this second break without merely replicating the pathways of common sense, since this would mistake the problem for the solution.

Relationality has been argued for by Franz Boas, Edward Sapir, and their students in anthropology, for whom the interaction among language, culture, and individual lived worlds was, and still is, of basic import. It fits the later Ludwig Wittgenstein, for whom actions in the world were formative of and not dependent upon the regularities that we summarize as a grammar. It fits Nelson Goodman s irrealism, according to which language provides the means of formulating versions of the world that are comparable to musical scores, pictures, and other nonverbal representations. It applies to phenomenologists such as Roman Ingarden, Maurice Merleau-Ponty, and Alfred Schutz, for whom one of the primordial facts of language is its interpenetration with experience. It applies to the work of the Marxist V. N. Voloshinov, the psycholinguist Ragnar Rommetveit, and the political philosopher Charles Taylor, who have attempted to synthesize inner logics with relational dependencies in interestingly different ways. We deal with most of these works in the chapters ahead.

Relationality can combine with irreducibility in various ways. One could say simply that the irreducible uniqueness of language lies precisely in how it relates to the world around itself. This yields a view in which what is essential is not inside the linguistic system as such but in its potential for entering into further relations in the world. Alternatively, one could maintain that language is capable of entering into coherent relations because in fact it remains stable, repeatable, and sui generis. It is precisely because an expression like “the table” has the meaning it does that it can be used in reference to both a kitchen table and a dining room table. This yields an expanded version of irreducibility, for it amounts to the claim that the sui generis system is a precondition and relationality is a contingent factor. First we define form, and then we add an overlay of context. Only by combining the two do we arrive at meanings as full as the ones in our opening exchange between Natalia and Jack. We need not try to decide among such alternatives in the abstract, as though we could legislate an answer. Rather, we ought to take the general point that the two theses are just that: propositions about the foundation of language, not exhaustive descriptions or categories of th...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Contents

- Preface

- 1 Introduction: Meaning and Matters of Context

- One Language the System

- Two Language the Nexus of Context

- Three Communicative Practices

- Index

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Language And Communicative Practices by William F Hanks in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Social Sciences & Sociology. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.