- 296 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Expansion And Structural Change

About this book

As a central institution that ensures equality of opportunity and social justice, the university is the most important channel of social mobility in modern societies. Over the past century, universities have assumed an important role in the political and cultural emancipation of women, minorities, and the lower socioeconomic classes. This expansion in educational institutions was not an isolated event in the years after the World War II, but rather a phase in a longer, secular process of modernization which started in the late nineteenth century and continues up to the present day.Expansion and Structural Change explores this development, focusing on the social background of students and the institutional transformation of higher education in several countries. Who have been the beneficiaries of this remarkable process of educational expansion? Has it made Western society more open, mobile, and democratic? These questions are analyzed from a historical perspective which takes into account the institutional change of universities during this century.Based on archival data for the United States, Germany, Japan, France, and Italy, this study combines both comparative and historical perspectives. It documents the political struggle of different social groups for access to univeristies, as well as the meritocratic selection for higher status positions. This work will be an indispensable reference for anyone searching for a comparative and historical analysis of higher education in the most advanced countries.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

1

Educational Expansion as Secular Process

1.1 Time Series in Comparison

The concept of educational expansion refers generally to the substantial growth witnessed by universities during the period between 1960 and 1975. This period is often associated with the politicization of universities and with the student movement, which are popularly seen as a result of the expansion. During these 15 years the educational system of West Germany experienced much that had been going on gradually over many decades in other countries: universities lost their status as institutions for the elite and were opened to the masses. This phase of rapid expansion was of short duration; the increase in enrollment returned to more normal levels in the mid-1970's, after which the period of rapid expansion appeared as a unique event at a time of predominantly liberal educational policies.

However, this expansion in educational institutions was in fact not an isolated event in the years after the Second World War but rather a phase in a longer, secular process. The educational systems of many industrializing countries have been expanding since the 19th century, and data are available to document this expansion, particularly that of universities, at least since the late 19th century. The curve of university expansion shows a long-term rise over the past century, and in fact hardly affected by the various economic cycles. From the time of German unification in 1870/1871 down to the First World War university enrollment grew in Germany at an annual rate of almost 2%, and during the interwar years the universities experienced a particularly rapid expansion, due in large part to the influx of the middle class and women.2 Between 1925 and 1932 the number of students rose from 86,000 to almost 140,000. The expansionary curve of these years then underwent phases of stasis and decline, finally resuming its upward climb again in the mid-1960's.

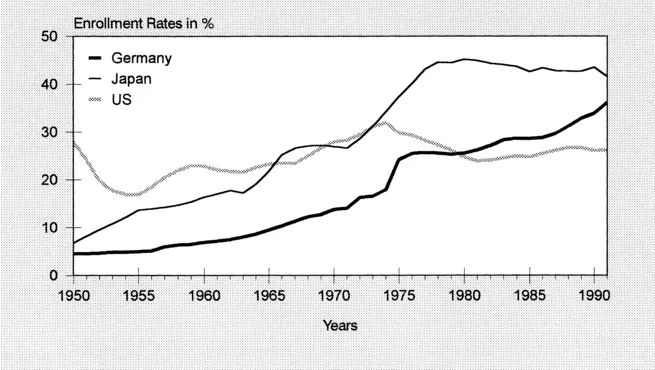

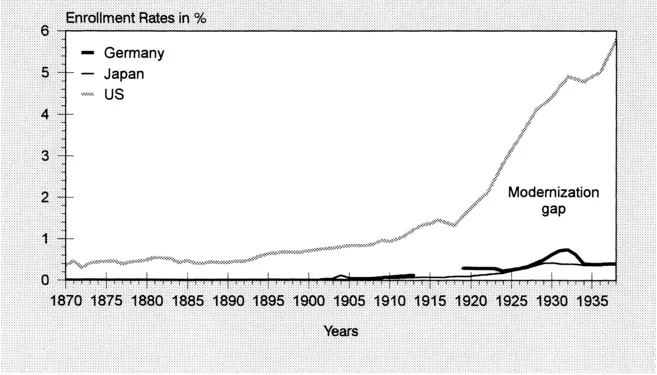

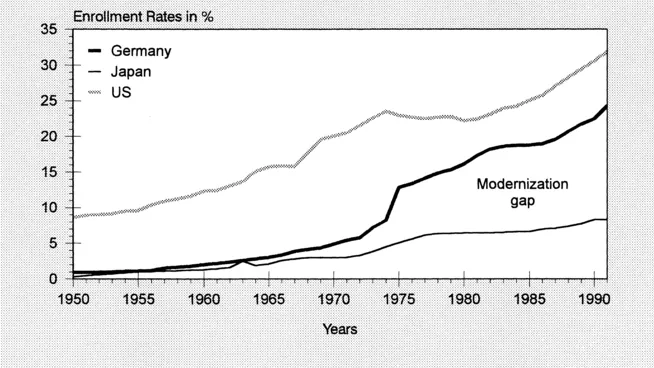

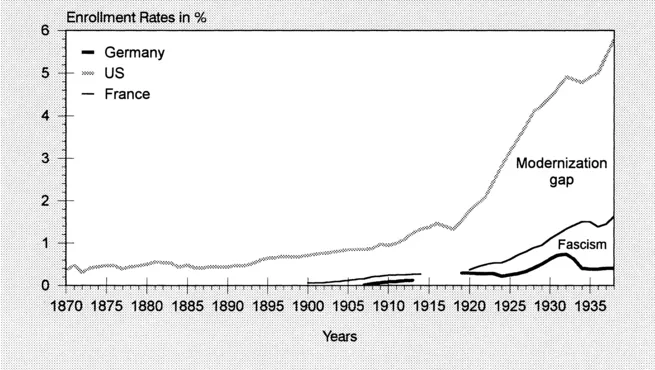

Figures 1.1-1.4 present the curve of the enrollment rates" in Germany, the United States, and Japan between 1870 and 1990 for men and women separately; Fig. 1.5 shows the enrollment rates for women in the United States, France, and Germany. These data show clear differences in the rate of growth both between the countries and between various periods within each country. Growth in the years before the First World War was comparatively modest, with expansion in the three countries developing similarly (although the lead of the United States in higher education was visible already before the First World War). In the interwar period the expansion in the United States and Japan (men) accelerated, while the economic and political catastrophes that befell Germany during this era are reflected in steep, reversed, and broken segments of its curve (Fig. 1.1, men). It was only in the 1960's that German universities then attained the growth which the United States (and to some extent men in Japan) had experienced already before the Second World War. Since the beginning of the 1970's the rate of educational expansion in the United States has been declining, so that in the late 1970's the respective curves have met. The two "late comers" (Japan, Germany) have surpassed the "first new nation" (Lipset 1963), at least with respect to enrollment rates in higher education. This, however, is true only for men. For women, the "modernization gap" between the United States, on the one hand, and Japan and Germany, on the other, is still evident, even though German women narrowed the gap during the 1970's and 1980's (Fig. 1.4).

Whereas women were allowed admission to university in Prussia only in 1907, in the United States they already made up 15% of university students in 1870. As in the case of their male counterparts, American women attended university in continually growing numbers from 1890 until the depression of the 1930's, when a leveling off is seen about 1932-1934. However, also in the United States the depression was unable to substantially hinder the educational expansion. Despite the nearly 13 million unemployed in 1933 (some 25% of the work force) the expansion continued with only a short stasis phase until the Second World War (Fig. 1.1).

1.2 Competing Theories of Educational Expansion

Why is it that ever growing numbers of students spend an ever longer period at universities, in spite of the fact that students' de facto expectations regarding professional careers have worsened with these growing numbers?4 What are the reasons for the constant growth in university enrollment?

The simplest explanation for this growth lies in a self-perpetuation of university education over several generations (inheritance effect). Once a liberal education policy has set in motion the expansion of universities, this expansion accelerates automatically over generations. It is an "iron law" of educational research that the children of university graduates attain on average a higher educational level than do children of those who did not attend university. Children of the working class who obtain a university education, then, no longer belong to the working class. Their children, in turn, without roots in the working class, enjoy a higher likelihood of obtaining a university education than do working class children. This multiplier effect in the proportion of university students is evident as early as the second generation. From one generation to the next, the educational level attained climbs continually, albeit with decreasing speed.6

This sort of growth can be seen as endogenous, as it derives from forces set in motion by the educational expansion itself. However, such endogenous growth cannot, by itself, explain the growth pattern as shown in Figs. 1.1-1.5. In the case of Germany, for instance, one can distinguish three periods: (a) that before the First World War, with a low growth rate; (b) that between the World Wars, with zero growth and extreme cyclical variations; and (c) that after the Second World War, with a high growth rate. The expansion in university enrollment is not maintained solely by endogenous forces, but is influenced by economic and political circumstances which, in terms of the educational system, can be termed exogenous.

There are many general theories about educational expansion, however, only few systematic efforts to explain the long-term growth which has characterized the history of the institution. Among the range of theories in the social scientific literature one finds at least three competing models of educational expansion: functionalist theories, theories of status competition, and a third model which will be termed here as "conflict theory" (Collins 1971, 1979). The central theses of these theories are summarized below, followed by an examination of the extent to which each is supported by historical data.

Functionalist Theories (Human Capital)

Functionalist theories are in agreement that educational expansion meets a

FIGURE 1.1 Enrollment Rates 1870-1939, Men

FIGURE 1.2 Enrollment Rates 1950-1991, Men

FIGURE 1.3 Enrollment Rates 1870-1938, Women

FIGURE 1.4 Enrollment Rates 1950-1991, Women

FIGURE 1.5 Enrollment Rates 1870-1938, Women

societal need; disagreement arises among them, however, regarding the definition of what this societal need is. The theory of human capital maintains that education raises labor productivity: highly trained personnel are more innovative, productive, and flexible than unskilled workers. Thus, seen from the perspective of society, education is an investment for future growth and modernization.7 In addition, the theory of human capital postulates a straightforward market relationship between the demand for trained personnel and university enrollment levels: times of economic growth are accompanied by university expansion while economic recessions are marked by declining numbers of university students. This view regards the labor market and the university as mutually regulating systems: university expansion does not continue endlessly but is limited by the demand for specialized qualifications. Although there are periods of over- or undersupply, this model regards the relationship between educational system and labor market as one approaching equilibrium.8

A second form of the functionalist explanation emphasizes the educational responsibility of the educational system. Universities as well as schools are seen principally not as conveying occupationally oriented knowledge but as socializing the young for the demands that their future occupation will put upon them. Bowles and Gintis (1978, p. 37), for example, stress the stabilizing effect of the educational system for capitalist production: "Since its inception in the United States, the public-school system has been seen as a method of disciplining children in the interest of producing a properly subordinate adult population. Sometimes conscious and explicit, and at other times a natural emanation from the conditions of dominance and subordinacy prevalent in the economic sphere, the theme of social control pervades educational thought and policy." Taking over from the family, educational institutions instill orientations toward the world that are necessary for the person's acclimatization to the working world.9 For instance, it is not a body of technical knowledge that is to be expected from a university education but a professional ethos, discipline, perseverance, and flexibility in responding to quickly changing conditions. Thus, the educational institutions produce the personality structure which is accommodated to different job demands: high school drop-outs for the monotonous assembly line, community college graduates for respectable administrative work, and university graduates for professional jobs.

The assumption that economic growth and modernization are the motor behind the expansion of educational institutions was questioned as early as the turn of this century by the Prussian economist and educational researcher Franz Eulenberg, who pointed out a paradoxical relationship between university and labor market (1904, p. 256): "Favorable economic conditions tend to limit university enrollment and unfavorable conditions to expand it." Eulenberg's observation represented an assault on modernization theories, which had traced university expansion to the rising demand by industry for technically trained personnel.10 Thus, even a century ago the integration of the university in the labor market did not seem to function as hypothesized by the theory of human capital, and as was still maintained by its proponents 60 years later.

Eulenberg supported his position with empirical data: the number of students at German universities had increased every year since 1866, even during the depression that severely affected economic conditions after 1875. Later, during the depression of the 1930's, it was estimated that between 80,000 and 100,000 university graduates were unemployed or had taken positions for which they were overtrained; despite this, however, the universities were experiencing a hitherto unprecedented flood of students.11

Aside from the periods of the two World Wars there have been only two periods in the history of German universities since 1866 during which the absolute number of students declined; one was at the time of the 1922-1923 hyperinflation which wiped out the savings of many middle class families, and the other was after the introduction in 1933 by the new Nazi regime of statutory ceilings for the number of university admissions in specific subjects. Data on university enrollments in France and the United States show that the expansionary curve in these countries continued to rise during these periods and was eventually brought to a halt only by the outbreak of the Second World War.

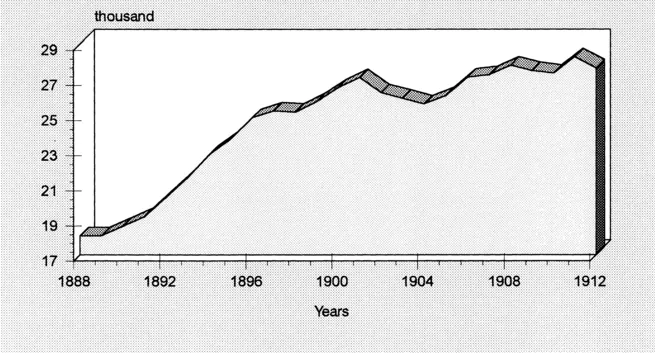

Figure 1.6 presents the enrollment levels at Italian universities between 1888 and 1912. The curve here offers further support for Eulenberg's view: despite the economic recession there from 1888 to 1902 the number of students increased dramatically, whereas matriculations declined over the subsequent years of economic upswing.12 These data provide an early indication of the "anti-cyclical" relationship between cycles of economic and of educational expansion (see Chap. 7).

Comparable data from the United Kingdom also confirm Eulenberg s view, as is shown by Stone's (1974) historical analysis of expansion in universities there. Enrollment levels at British universities witnessed avirtually unbroken expansion throughout the second half of the 19th century and continuing up to the Second World War. The number of new students (only men) rose from 1323 in 1870 to 2507 in 1903 - an average annual increase of 1.9%. 13 The United Kingdom was also subject to the

FIGURE 1.6 Number of Students Enrolled at Italian Universities, 1888-1912

depression of the third quarter of the 19th century; however, student numbers did not decline. "In 1879 there began a profound depression that hit agriculture particularly hard, and especially those areas devoted exclusively to arable farming. Rents fell dramatically, and many tenants and rural landlords found themselves in severe difficulties. Not only were the landed gentry very hard hit, but the finances of the colleges suffered a crippling blow, from which they did not recover until after the First World War. The graph of admissions continued to soar triumphantly past this economic watershed as if it never existed..."14 The upward course of university expansion in the United Kingdom also continued unabated during the depression of 1928-1932.

These data show that it is not economic upswing but precisely economic downturn which accelerates educational expansion - in apparent contrast to all the laws of economic rationality. Why is it that students flock to the universities at times when the career opportunities offered by a university education seem to be in decline? If the expansion of universities is independent of the business cycle, economic theories of market regulation mechanisms cannot be expected to contribute much to explaining the causes of the expansion.

Individual Status Competition

With the chronic overproduction of university graduates since, at the latest, the early 1970's this question has again become a central issue in t...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title

- Copyright

- Contents

- Preface

- Acknowledgments

- 1 Educational Expansion as Secular Process

- 2 Educational Expansion and Social Background

- 3 The Opposition to Educational Expansion

- 4 Institutional and Social Differentiation in Higher Education

- 5 From Patronage to Meritocracy

- 6 Expansion in Higher Education 1960-1990

- 7 Cyclical Variations in Higher Education

- 8 Conclusions

- Notes

- Appendix I: Sources

- Appendix II: Enrollment Rates in Higher Education 1850-1992

- References

- Index

- About the Book and Author

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Expansion And Structural Change by Paul Windolf in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Social Sciences & Sociology. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.