eBook - ePub

Storming The Heavens

Soldiers, Emperors, And Civilians In The Roman Empire

- 288 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

In the closing years of the second century B.C., the ancient world watched as the Roman armies maintained clear superiority over all they surveyed. But, social turmoil prevailed at the heart of her territories, led by an increasing number of dispossessed farmers, too little manpower for the army, and an inevitable conflict with the allies who had fought side by side with the Romans to establish Roman dominion. Storming the Heavens looks at this dramatic history from a variety of angles. What changed most radically, Santosuosso argues, was the behavior of soldiers in the Roman armies. The troops became the enemies within, their pillage and slaughter of fellow citizens indiscriminate, their loyalty not to the Republic but to their leaders, as long as they were ample providers of booty. By opening the military ranks to all, the new army abandoned its role as depository of the values of the upper classes and the propertied. Instead, it became an institution of the poor and drain on the power of the Empire. Santosuosso also investigates other topics, such as the monopoly of military power in the hands of a few, the connection between the armed forces and the cherished values of the state, the manipulation of the lower classes so that they would accept the view of life, control, and power dictated by the oligarchy, and the subjugation and dehumanization of subject peoples, whether they be Gauls, Britons, Germans, Africans, or even the Romans themselves.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Storming The Heavens by Antonio Santosuosso in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & World History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

All-Rich and Poor, Well-Born, and Commoners—Must Defend the State

[Marius] enrolled soldiers, not according to the classes in the manner of our forefathers, but allowing anyone to volunteer, for the most part of the proletariat. Some say that he did this through lack of good men, others because of a desire to curry favor, since that class had given him honor and rank. As a matter of fact, to one who aspires to power the poorest mail is the most helpf ul, since he has no regard for his property, having none, and considers anything honorable for which he receives pay.

Sallust, The War with Jugurtha lxxxvi.2-3

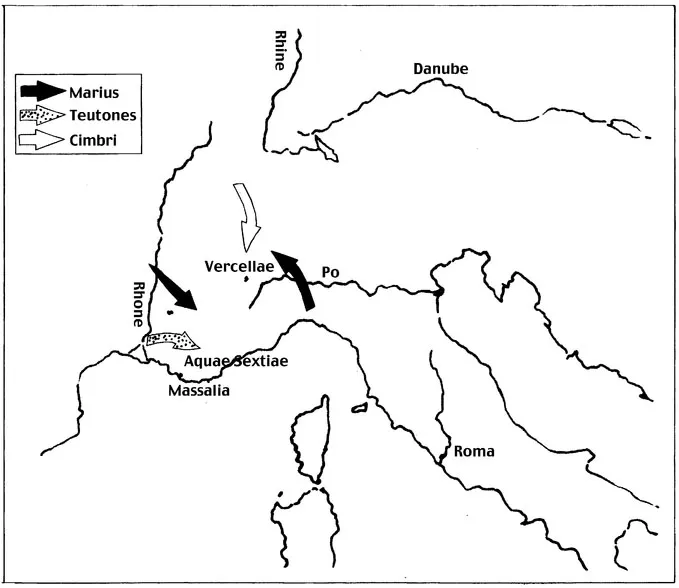

Once he learned that the barbarians—Germans mainly but also some Celts—were approaching the mountains, the consul Gaius Marius (ca. 157-86 B.C.) crossed the Alps quickly. Thousands of legionnaires had already fallen in battle to these tall, ferocious, blue-eyed warriors.1 Now divided into two main groups, the barbarians had decided to invade the Italian northern plains. One group, the Cimbri, were coming from the north through Noricum (the region northeast of the Alps). The other group, the Teutones, facing Marius, were coming from the west, the land of the transalpine Gauls. The year was 102 B.C.

Marius had gained his military reputation in North Africa against the Numidian king Jugurtha, who, chained and dejected, had been exhibited in Marius's triumph in Rome and would soon lose his mind in a Roman dungeon. In Africa the consul had also won his soldiers' hearts and loyalty. His sense of justice, firmness of character, and willingness to share deprivations with his soldiers and reward them for their bravery had endeared him to the troops. Moreover, he was a leader who brought great financial gains. His triumphal procession had displayed 3,007 Roman pounds (eleven ounces each) of gold, 5,775 pounds of uncoined silver, and 287,000 drachmas.2 He also commanded vast popular support in Rome, though he lacked the basic ingredients of political power—eloquence, wealth, and family background; the aristocracy viewed him with fear and contempt. For the Roman ruling group, there were many unpalatable details about Marius. His ancestry was modest, he had not been born in Rome, and he was not awed by the senators' social status and family history. He used to taunt the aristocrats that his nobility was carried in the wounds of his body, not on "monuments of the dead nor likeness of other men."3 The commoners who would come to see him as their champion respected his honesty, as well as his tendency to challenge and rebuke his reputed superiors in society.

Marius's campaign against the Teutones was a model of the Roman art of war in the later stages of the republic. In preparation for the confrontation, which was causing great fear in Rome, this man, who was ambitious, quarrelsome, and fond of war, proceeded to challenge the invaders in a methodical, logical way. He carefully trained his troops both mentally and physically, putting them through long marches and quick races in short bursts and training them to carry their own baggage.4 When he arrived close to the enemy, first attentions were devoted to defense. He set up a fortified camp near the River Rhone in Gaul. In a precaution typical of the Roman art of war, he made sure that abundant supplies were stored in the camp and that if more were needed they could arrive in a speedy and easy manner. Engineering would help with the latter: The Rhone's estuary into the Mediterranean was silted with mud, sand, and clay, allowing only a slow, difficult journey upstream. Marius built a canal connecting the river with a bay that provided protection from the bad weather and access for large ships.5

Upon their arrival the Teutones and their allies, the valiant warriors known as the Celtic Ambrones, set up camp nearby and challenged the Romans to come out of their fortified camp. It was an enticement that the legionnaires could hardly resist. Yet in the best spirit of another Roman characteristic, Marius and his officers were able to hold their troops in check. It was difficult and at times seemed almost impossible, for the legionnaires often desired to leave their posts and respond to the Teutones' attacks against the camp. But Marius intended to get his men accustomed to the savage appearance of their enemy, their war cries, their equipment, and their movements in order to transform "what was only apparently formidable, familiar to their minds from observation."6

Finally, after storming the Roman camp unsuccessfully, the Germans decided to bypass Marius and proceed toward the mountain passes. Plutarch puts the Teutones and the Cimbri, who were operating north of the Alps, at 300,000, a number that he insists was less than the one mentioned by other authors.7 The Teutones' marching column was so long that it took six days to pass the Romans. Thus it became time for Marius to break camp. He followed close, never forgetting, however, to fortify his camp and place it in a strong position at night.8 The moment for engagement came when they arrived at Aquae Sextiae (Aix-en-Provence) in the proximity of the Alps (see Figure 1.1).

Marius's preparations were again meticulous. The Aquae Sextiae camp was set in a strong position but, strangely, away from a river running near the enemy camp. At the moment of confrontation, it seems Marius wanted to place his troops in a situation wherein their desire to win would be intensified by the need to secure a water source. Actually, access to the water became the incidental trigger for the battle. Taking advantage of the fact that the barbarians were eating or engaged in leisure, Roman servants moved to the river to fill their containers. Once there, they came upon a group of bathing barbarians, who called other tribesmen to their aid. The Ambrones, although heavy with the barely completed dinner and their minds inebriated by wine, rushed to the spot, a move that triggered the legions' Ligurian soldiers to press forward to succor their servants. The clash was harsh and violent with both sides, Ambrones and Ligurians, uttering similar war cries since both claimed a similar descent, likely Celtic. (The Ligurians lived in the area nearby the modern city of Genoa.) When other legionnaires joined the Ligurians, the Ambrones fled toward their camp, their blood and bodies polluting the river water. As they reached the camp, an unusual spectacle awaited both fugitives and pursuers. The barbarian women dashed forth, swords and axes in hand, calling their men traitors and attacking the Romans, sometimes with their bare hands. The struggle ended at night when the Romans withdrew to their camp.9 It was a scene repeated a year later when Marius confronted the Cimbri at Vercellae. When the women, dressed in black garments, saw their men fleeing from the battlefield and reach for the wagons where they stood, they slew them with their own hands before killing their children and taking finally their own lives.10

FIGURE 1.1 Marius Against the Teutones and the Cimbri, 102-101 B.C.

Marius's men spent the night in "fears and commotions," for the daytime fight had prevented them from fortifying their camp with a palisade or a wall, and the enemy facing them was numerous. Wails, howls, and shouts of grief and of revenge reached them from the enemy camp, mourning the Ambrones, casualties. No attack came during the night, and none the day after.11 Yet battle was inevitable.

The barbarian camp was also located in a strong position, atop slopes and protected by ravines. In preparation for the confrontation Marius detached 3,000 men to lie in ambush in a wooded area near the enemy camp, ordering them to strike at the enemy's rear if the opportunity arose. Then he made sure that his soldiers were well fed and took a good rest. At daybreak he sent his cavalry on the plain and lined his infantry in front of the Roman camp, which had been set on a hill. It was a clever deployment that used the terrain to the utmost (his soldiers would have the advantage of height over the opponent and secure rear and flanks); the cavalry threatened the enemy flanks, and the men in ambush, when they came out of hiding, would bring the element of surprise to deliver the killing blow.

The Teutones and the remaining Ambrones obliged by rushing uphill, probably deployed in large squares with a depth equal to their front, as the Cimbri would fight at Vercellae.12 It was enticing for Marius's soldiers to charge downhill, but Marius relied on their discipline so that their desire to fight would not imperil the situation. He sent his officers along the line with specific orders: Do not charge; launch your javelins (pila) as the enemy rushes forward, then use your sword (gladius) as they come face to face and hit with your heavy shield (scutum) to push them back. Those were instructions that he himself carried out, for "he was in better training than any of them, and in daring surpassed them all."13

Having rushed uphill, the Teutones must have been out of breath when they came to grips with the Romans. Moreover, their blows and the clash of their shields, originating from the lower ground, must have been weak. In the meantime their large numbers must have been a handicap, for disorder reigned in their rear. This was the moment that the 3,000 Roman troops in ambush had been awaiting, and they hit the enemy's rear. The barbarian array broke up and fled, likely being pursued and cut down by the cavalry deployed in the plain. Counting their dead and prisoners, the tribesmen left some 100,000 people on the battlefield. So many human bones covered the terrain afterward, it was said, the people of nearby Massalia fenced their vineyards with the bones of the fallen.14 A year later the Cimbri, who had finally come across the Alps, met a similar defeat at Vercellae in northern Italy. About 60,000 fell prisoner; double that number perished on the battlefield. Marius again was the winning general.15

Marius's victories became part of Rome's collective memory and were celebrated centuries afterward. And although the clashes at Aquae Sextiae and Vercellae are splendid examples of the way the Romans carried out their brand of war, even more important for the military future of the state was Marius's recruiting reforms, coming about four years before the battle in transalpine Gaul.

Recruiting All Citizens

In 107 B.C. Gaius Marius opened the ...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title

- Copyright

- Dedication

- Contents

- List of Figures

- Acknowledgments

- INTRODUCTION

- 1 ALL—RICH AND POOR, WELL-BORN AND COMMONERS-MUST DEFEND THE STATE

- 2 ARMIES OF PILLAGERS

- 3 JULIUS CAESAR: THOUGHTS AND ACTIONS OF A COMMANDER

- 4 OF GODS, MILITARY LEADERS, AND POLITICIANS

- 5 "MY SOLDIERS, MY ARMY, MY FLEET"

- 6 HOW TΟ MANAGE AN EMPIRE: STRENGTHS AND PITFALLS

- 7 ENEMIES ON THE BORDERS, VIOLENCE AT HOME: SOLDIERS AS THE MAKERS OF EMPERORS

- 8 ROME IS NO MORE: THE END OF THE EMPIRE

- EPILOGUE

- Glossary

- Appendix I: Time Line, 218 B.C.-A.D. 476

- Appendix II: Roman Emperors, 27 Β.C.-A.D. 476

- Selected Bibliography

- Index