eBook - ePub

Places of Encounter, Volume 2

Time, Place, and Connectivity in World History, Volume Two: Since 1500

- 304 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Places of Encounter, Volume 2

Time, Place, and Connectivity in World History, Volume Two: Since 1500

About this book

First Published in 2018. Using a place-based approach by focusing on specific locations at critical historical moments of historical transformation, "Places of Encounter" provides a unique alternative to world history anthologies or survey texts.Students will experience the narrative of historic individuals as well as modern scholars looking back over documentation to offer their own views of the past, providing students with the perfect opportunity to see how scholars form their own views about history.This text can be purchased as two volumes, providing a breadth of information for survey courses in world history.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Places of Encounter, Volume 2 by Aran MacKinnon, Aran MacKinnon,Elaine McClarnand MacKinnon in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & World History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

Cape Town

At the Cross-Currents of the Atlantic and Indian Ocean Worlds

(1500–1800)

(1500–1800)

ARAN S. MACKINNON

I FIRST BECAME FASCINATED WITH THE IMPORTANCE OF CAPE TOWN WHILE wandering the streets of the ancient port city of Melaka (Malacca), thousands of miles away in Malaysia. I was there en route to graduate school in South Africa. Meandering down a street, I came across the very rough and shabby-looking remains of an old fort. While scanning the sun-bleached bricks and stones that formed an archway, I spotted the unmistakable imprinted symbol of the Vereenigde Oostindische Compagnie, or VOC, the Dutch East India Company. Around the historic Dutch quarter of the town, I could visualize the entire grand design of the trading empire the VOC carved out in the seventeenth century. In that moment I realized the great significance of South Africa’s Cape of Good Hope as the key stepping stone to the Indian Ocean world of spices, gems, timbers, teas, and other luxuries. Here lay the object of long-sought-after European commercial desires. But my passion for history remained focused on Africa, and I set off for Cape Town, where the VOC established an early foothold.

I am always struck by a profound sense of the convergence of historical and cultural forces in the Cape Town region. Like the Benguela ocean current pressing up from the Antarctic and the Agulhas current coursing down the Mozambican coast to meet it off Cape Point, these forces have heaped a myriad of people and ideas together at the southern tip of the continent. People from around the world have long sought safe haven here, yet when I first arrived in South Africa in 1985, it was a country torn apart by racial and class conflict. P. W. Botha, state president of the whites-only government, had just extended a state of emergency in the Cape to further the clampdown on African, Indian, and Coloured (referring to people of mixed ethnic descent; collectively, all these groups were referred to as black) opposition to one of the world’s most notorious racist regimes. Driving in from the airport, I could see township (the forcibly segregated areas designated for Africans) residents throwing rocks in protest at affluent whites as they passed by on their way into the whites-only city. As a white, I had the guilty privilege of staying in the beautiful suburb of Rondebosch, nestled in the shadow of Table Mountain. This was where Dutch East India company employees were first allowed to settle their own farms along the Liesbeek River. Rondebosch later served as a staging ground for the Boers (early white Dutch settlers, later known as Afrikaners) to penetrate African lands and displace the Khoe herders who had long lived in the region. A favorite weekend drive of mine, down to the Cape Point national wildlife refuge, took me past beautiful white-owned homes and vast shanty settlements where Africans struggled to eke out a living in fear of brutal police harassment. It also brought me near the infamous Pollsmoor prison where Nelson Mandela, then condemned by the white government as a terrorist but later celebrated as the country’s first black president, was incarcerated. In my mind there was clearly much to be learned of this place and its history, where people from around the world had converged and clashed in their struggles with the land and each other. What continues to captivate me most about Cape Town is the way the place and the people invite you in to explore these convergences that are cast in such sharp relief in its history.

This chapter will highlight how Cape Town and its environs provided the setting for the bridging of the Atlantic and Indian Ocean worlds. It also shows how the powerful forces of white settlement and slavery had profound effects on African societies. The ensuing displacement and subordination of Africans and Asians set the stage for the later continent-wide intrusion of European colonialism. Other key themes in the chapter include the role of women in shaping society, the importance of the environment and how humans interacted with it, the construction of racial and ethnic identities, and the emergence of a cosmopolitan, globally connected society.

Cape Town and the World: Cultural Blending in an Abundant Environment

Perhaps the best way to appreciate the global significance of Cape Town is to see its geographic location in relation to the region and the world. Cape Town is situated in a wide, sheltered bay on the western shore of the southernmost part of Africa. (See Map 1.1.) Some thirty-five miles further south is the famed Cape of Good Hope, so called by the Portuguese king John II (1455–1495) as an expression of his maritime country’s aspirations to profit from trade in the Indian Ocean region beyond Africa. Just a mile or so to the east of that is Cape Point. Standing at the tip of Cape Point, one can look across False Bay and see the coastline of the great African continent stretching to the northeast. Although this point is not technically the southernmost tip of Africa, it is the symbolic geographic turning point for maritime travelers passing from the Atlantic world into the Indian Ocean circuit of trade. It is the same point ancient Phoenician mariners might have passed in a circumnavigation of the continent over 2,600 years ago. One cannot but be in awe of this historic geographic location.

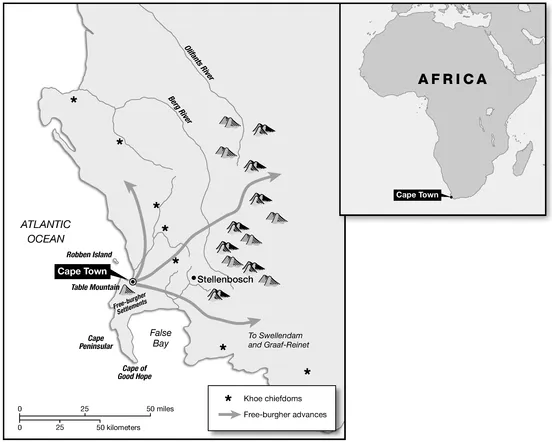

Map 1.1. Khoe Chiefdoms, ca. 1650

The Cape of Good Hope peninsula and environs have played host to a variety of people and societies. The local environment supported indigenous pastoral Khoe chiefdoms, which ranged over the coast and interior. The strategic location of the Cape later attracted Europeans seeking to connect to commercial opportunities in the Indian Ocean region. Thereafter, interdependence between whites and Africans gave way to conflict and the emergence of one of the world’s most unequal societies.

The Cape of Good Hope peninsula and environs have played host to a variety of people and societies. The local environment supported indigenous pastoral Khoe chiefdoms, which ranged over the coast and interior. The strategic location of the Cape later attracted Europeans seeking to connect to commercial opportunities in the Indian Ocean region. Thereafter, interdependence between whites and Africans gave way to conflict and the emergence of one of the world’s most unequal societies.

The terrain surrounding Cape Town is among the most impressive and ruggedly beautiful in the world, boasting magnificent mountains and seaside cliffs; the pounding surf of the wild southern oceans; the arid, scrubby interior of the Karoo Desert; and the well-watered and fertile valleys where wine making and citrus growing abound. The weather alternates between warm, dry, Mediterranean summers and wind-lashing cool rains in the winter, justifying both of the region’s nicknames: Cape of Storms and the Fairest Cape. Local lore speaks of healthful air to breathe, maintained by strong winds that blow away accumulated haze. On the top of majestic Table Mountain, which dominates Cape Town as a massive geological backdrop, a delicate ecosystem persists, with over nine thousand species of plants. It is one of the world’s most diverse vegetation zones. At the base of the mountain, the shores of Table Bay provide a safe harbor, endless beaches, forested kloofs (valleys), and the setting for one of the world’s most fascinating human stories. It was here, in Cape Town itself, where Africans gathered and held councils, passing ships left letters under a white-washed stone to be gathered by sailors for delivery as they returned to other ports of call, and a myriad of peoples, economic systems, cultures, and historical aspirations converged. It also became, for better and worse, the gateway for the intrusion of European imperialism and settlers into southern Africa.

This dynamic synthesis of nature is mirrored in the human landscape. The built city bears the unmistakable imprint of Dutch and British colonial architecture, and African styles are found everywhere, but there is also a powerful underlying Asian influence, with a blending of Malay and Islamic cultures. The cuisine also highlights the syncretism (the social blending of cultures and people) of African, Asian, and European influences. The classic Cape Malay dish, bobotie, is accented with curry powder and raisins. Everywhere I looked, the creolized fashions, people, landmarks, plants, and foods remind me that dynamic historical forces have made Cape Town one of the most fascinating cosmopolitan centers in the world.

Cape Town and the Emerging Global Trade, ca. 1500 CE

Cape Town is said to have had accidental foundations. Many of the people who, throughout time, have touched upon her shores—and even recent historians—have argued that it was intended to serve merely as a rest stop or replenishment way station for vessels making their way to the more important and highly prized trading regions of southeast Asia and China. This earned it the dubious title “Tavern of the Seas.” Such characterizations, however, mistake the forces of history that early on bound people, both European travelers and indigenous Africans, to this place. Cape Town was central to the early emergence of globalization and interconnections that made possible the rise of merchant trading empires. Between the early 1500s and the early 1800s, all the major forces of the early modern world came together in the Cape. Europeans embarking on long-distance voyages for trade and exploration connected southern Africa to seafaring global trade networks for established and new exotic goods, emergent networks of finance and investment, new techniques for farming, and powerful technologies for war. Europeans in the Cape also negotiated ideas about how Africans were seen and understood both in Africa and around the world as the “other”—that is, as people set apart by these European observers as different culturally or ethnically. And together, Europeans and Africans forged new, if decidedly unequal, societies that were in turn connected to the Atlantic and Indian Ocean circuits and to the world beyond.

Beginning in the early 1400s, northwestern Europeans were on the move, transforming their productive capacities, using new technologies (especially military and maritime) to expand overseas, and developing the new economic system of merchant capitalism. Merchant capitalism entailed accumulating and reinvesting profits from global trading in further overseas ventures. The Portuguese were the first to use this system to build an empire in South America and parts of Africa; later the Dutch and English outpaced Portugal’s commercial activity. These enterprises necessitated taking land and rendering indigenous peoples into compliant workers on this land, which they had formerly claimed as their own. Where this could not be done, as in both America and South Africa, local societies were pushed aside and new labor was introduced, most often in the form of slavery.

As a precursor to the era of industrial capitalism (c. 1800), the Dutch, like the English in North America, forged the most advanced system of merchant capitalism in the form of their East India Company. They ventured into the Atlantic world, seeking to reconnect to the spices and luxury products of China, Indonesia, and India. With the rise and expansion of Islam and the threat of infectious disease from Asia, maintaining regular trade traffic to the east from Europe was a challenge. Powerful Islamic states demanded higher tariffs and posed greater competition, so the Dutch sought alternative routes to Asia.

The People and the Environment: Local and Regional Connections

Of course, human history in the Cape did not begin with the arrival of the Portuguese or the later Dutch. KhoeKhoe or just Khoe (“men of men” or the “real people”) and San (or Soaqua) people had been well established in the region long before the whites. They and other African states and societies in the interior had engaged in long-distance trade for many centuries across the southern part of the continent and with the Indian Ocean trade network. By about 1000 CE, Africans had established the towns of Toutswemogala and Mapugngubwe along the Limpopo River. Their legacy of glass beads, cowry shells, sophisticated ironwork, and fabulous gold statues are testament to their impressive advances. These efforts helped connect foragers and pastoralists in the south with farmers who planted crops and kept cattle in the north and along the coast, eventually leading to a vibrant regional trading network centered on the goldsmiths and ivory hunters of Great Zimbabwe and linked to the Indian Ocean.

San and Khoe people formed the earliest communities, making the Cape region their home. They shared a common heritage from what were probably the first modern humans in the world, and as they settled across southern Africa they adapted to the demands of an often unforgiving environment. They also shared interrelated strategies in the building of communities. San hunting and foraging communities lived in the interior, were decentralized, and were small in number. There were likely only about twenty thousand San when the first whites arrived in the Cape. San hunting strategies often included the practice of robbing stock from nearby herding communities—a practice that led to vilification and retributions from later European farmers. San relations with the Khoe were open and fluid, with a range of social and economic links that blurred the lines between them. Indeed, many Khoe who moved into the and interior or lost stock due to wars or disease adopted a San lifestyle, making the two groups indistinguishable and creating a dynamic social formation sometimes referred to as KhoeSan.

The Khoe were herders of sheep and cattle. They emerged from earlier groups of Tshu-Khwe-speaking people who probably dispersed from an area of modern Botswana about fifteen hundred years ago. The Khoe had already started to acquire livestock—fat-tailed sheep and the “Africander” long-horned cattle—when they arrived in the Cape. Their chiefdoms were larger than San clans, comprising up to two thousand members, and the overall Khoe population grew to possibly over one hundred thousand by the mid-seventeenth century. Overall, the Khoe’s herding and trading lifestyle made them more inclined to engage in trade and work relations with whites than the San hunter-gatherers, who could retreat to the Cape interior, and so the Khoe were the first in this region to face the impact of white settlement.

The KhoeSan were probably, and understandably, suspicious about the intrusion of white colonizers onto their lands. What began as simple forays by the Europeans to find meat and water developed into permanent white settlement and the displacement of indigenous peoples. As this pattern emerged, settlers began to develop ways of thinking that justified their desire to gain wealth and power, including ideas about ownership and cultivation of the land. They were convinced that their more intensive use of the soil was superior to indigenous practices, which to them seemed less productive. Many European perceptions of Africans demonstrated biased misunderstandings and a disdain for the indigenous societies. Early European maps of the Cape and interior showed vast expanses of vacant land—presumably open for white settlement—and only a sprinkling of indigenous peoples. Paintings of the KhoeSan portrayed them in misshapen or even bestial forms. Early Europeans also devalued KhoeSan culture, showing little appreciation for San rock paintings of their engagement with nature and spirituality. Europeans did not even acknowledge that the Khoe had an intelligible language, let alone make an effort to learn it. They referred to the Khoe as “hottentots” because their speech sounded like turkeys clucking, and they called the San “bushmen” because they lived in an “uncivilized and dangerous” wilderness. As the pace of imperial expansion intensified, Europeans established similar views and derogatory terms for indigenous people across the globe, including for Indians in the Americas and Asians in the Far East.

Portuguese Forays and KhoeSan Responses

The Portuguese were the first Europeans to arrive in the Cape. This small Iberian nation set the pace for exploration and early trade missions around the coast of Africa. Beginning in the 1420s, Prince Henry, known as “the Navigator,” sought to connect with the mythical Christian king Prester John and the riches of Asia by marshaling a wealth of seafaring and cartographic knowledge about Africa and beyond. He coordinated and spurred a growing fleet to push south, past the fabled “end of the earth” at Cape Bojador on the West African coast, beyond which few if any Europeans had previously ventured. This set the stage for a vast Portuguese trading empire. By the 1460s, Portuguese ships were trading along the West African coast and laying the ominous foundations for the slave trade. The Portuguese cultivated a sense of cultural and technological superiority. By the later 1480s, they arrived in the Cape of Good Hope convinced both of the righteousness of their mission to spread Christianity and commerce in the Indian Ocean region and of their entitlement to the supplies and resources they needed.

The arrival of Portuguese mariners in the Cape illuminates the deeply ambiguous economic and cultural encounters between Europeans and Africans. While Europeans lionized as heroes Bartolomew Dias, the first-known European to round the Cape of Good Hope in 1488...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title

- Copyright

- Dedication

- Contents

- List of Features

- About the Contributors

- Preface

- 1 CAPE TOWN: At the Cross-Currents of the Atlantic and Indian Ocean Worlds (1500–1800)

- 2 SALVADOR DA BAHIA: A South-Atlantic Colonial Crossroads (1549–1822)

- 3 NAGASAKI: Fusion Point for Commerce and Culture (1571–1945)

- 4 LONDON: Emerging Global City of Empire (1660–1851)

- 5 GORÉE: At the Confluence of the Atlantic, Saharan, and Sahelian Worlds (1677–1890)

- 6 PARIS: City of Absolutism and Enlightenment (1700s)

- 7 CALCUTTA: A Central Exchange Point for Widely Separate Worlds (1700–1840)

- 8 SHANGHAI: From Chinese Hub Port to Global Treaty Port (1730–1865)

- 9 ALGIERS: A Colonial Metropolis Transformed to a Global City (ca. 1800–1954)

- 10 GALLIPOLI: War's Global Concourse (1915)

- 11 ST. PETERSBURG: The Russian Revolution and the Making of the Twentieth Century (1890–1918)

- 12 KINSHASA: Confluence of Riches and Blight (1800s–1900s)

- 13 BERLIN: A Global Symbol of the Iron Curtain (1945–1991)

- 14 NEW YORK: Opportunity and Struggle in a Global City (1911–2011)

- 15 DUBAI: Global Gateway in the Desert (1820–2010)

- Index