eBook - ePub

Are Leaders Born or Are They Made?

The Case of Alexander the Great

- 114 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Are Leaders Born or Are They Made?

The Case of Alexander the Great

About this book

This book discusses the psychodynamics of leadership-in and relies on concepts of developmental psychology, family systems theory, cognitive theory, dynamic psychiatry, psychotherapy, and psychoanalysis to understand Alexander's behaviour and actions.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Are Leaders Born or Are They Made? by Elisabet Engellau,Manfred F. R. Kets de Vries in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Psychology & History & Theory in Psychology. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

PART I

HISTIOGRAPHY

CHAPTER ONE

Setting the stage

Alexander the Great, one of the greatest generals of all time and one of the most powerful personalities of antiquity, was born in 356 BC in Pella, Macedonia (Baynham, 1998; Bosworth, 1988; Bury & Meiggs, 1983; Freeman, 1999; Green, 1991; Hammond, 1998; Hogarth, 1977; Lamb, 1945; Stewart, 1993). Although the Macedonians, whose territory occupied the area around present-day Thessaloniki in northern Greece, considered themselves part of the Greek cultural sphere, many Greeks regarded them with contempt. In the eyes of the Greeks, the Macedonians were a mere offshoot of the original stock. They spoke a Greek dialect, to be sure, but they were led by a backward monarchy and their nobles (little more than barbarians) pursued the manly pleasures of hunting, drinking, frolicking, and casual fornication, the latter quite indiscriminately with both men and women.

Parental disharmony

In 359 BC, King Perdiccas III, then ruler of Macedonia, died in battle. His infant son, Amyntas, was expected to succeed him, with Perdiccas’s brother Philip (Alexander the Great’s father) as his regent. Philip, however, usurped his nephew’s throne, crowning himself King Philip II. With that bold step he set the stage for the meteoric rise of his country’s fortunes and its entry on to the world stage (Cawkwell, 1981).

King Philip, who had been educated by Epaminondas (the finest military strategist of Greece before Alexander), was a brilliant ruler and strategist. In just a few decades he conquered most of Greece. He was fortunate in that Macedonia was rich in gold and silver mines—particularly as the empire expanded—giving him financial clout that was matched only by King Darius of Persia. These riches enabled him to maintain a formidable mercenary force and to bribe senior officials in the various surrounding kingdoms and city-states when it suited his political purposes.

As the ruler of his country, King Philip exercised absolute control over Macedonian affairs. He was an astute politician with a good sense of realpolitik and a knack for playing politicians off against one another. The fact that he was able to transform Macedonia from a backwater to one of the most powerful states in the Greek world was a tribute to his commanding personality, his talents as a diplomat, and his exceptional skill as a general.

Alexander’s mother, Olympias, was the orphaned daughter of King Neoptolemus of Epirus, an area located in what is now Albania. In the fall of 357 BC she married Philip in a union arranged for political purposes, an alliance intended to safeguard a relationship with a potentially troublesome neighbour.

Olympias was beautiful, but she was possessed by a terrible temper and wilfulness which, when coupled with her great intelligence, made her an extremely difficult and complex person to live with. According to the documentation of the time, Olympias could be cruel, stubborn, headstrong, sullen, and meddlesome. She rarely either hid or restrained her emotions and was prone to mood swings, ranging often from one extreme of feeling to another. Her quarrelsome temper put her at war with Philip (and him at war with her) for most of Alexander’s childhood.

Olympias, having been initiated into the cults of Dionysus, was an eager devotee of mystic rituals and torch-lit fertility rites. Her frequent participation in Maenadic frenzies added to the turmoil in Alexander’s home life. As a devoted Bacchant, she often led the processions herself, sacrificing animals and drinking their blood. Among the more bizarre habits noted by her contemporaries, she kept an assortment of snakes for religious rites all over the place, including in her bed—an endeavour that must have discouraged conjugal visits by her husband (Plutarch, 1973). These strange habits led Philip (and his entourage), who were subject to the many superstitions of that age, to wonder whether she was perhaps an enchantress, possessing dangerous magical powers.

Tradition tells that Olympias was descended from Achilles, the mythical hero of the Iliad, while Alexander’s father, Philip II of Macedonia, was said to descend from Zeus’s son Heracles. Both Olympias and Philip had dreams foretelling Alexander’s conception, and these dreams seem to bear out the regal heritage. Legend tells that soon after the marriage Olympias dreamed that she was impregnated by a thunderbolt as fire flooded her body (later spreading out across the earth). (According to popular myth, Zeus was the wielder of thunderbolts.) In King Philip’s dream he sealed her womb with the image of a lion. The most renowned seer of that time was invited to interpret their dreams (so the legend continues), and he concluded that Olympias was pregnant and that the child would have the character of a lion (Arrian, 1971; Lane Fox, 1994).

In keeping with Macedonian tradition, Philip had four lesser wives and many mistresses. (Diplomat that he was, he was said to take a new wife with every war in an effort to secure the boundaries of his kingdom through political marriages that showed his goodwill towards kingdoms worth conciliating.) Although Olympias could accept his affairs with women (and even men), she would not have brooked any threat to her position as the reigning queen—the queen-mother-to-be—and to her son’s position as the crown prince and future king. Any hazard to this position incurred her murderous temper. She had a reputation for ruthlessness and seemed prepared to dispose of her enemies if necessary. Philip and Olympias had one more child together, a daughter named Cleopatra. Thereafter, it can be assumed (given their conflict-ridden relationship), sexual intercourse ceased.

Queen Olympias’s only real love—a love that was total and all-consuming—was for her only son. She was often jealous, vindictive, and extremely protective of Alexander, who would idolize his mother as long as he lived. While her son was growing up, she made sure that many of the people in his inner circle were associated with her family. She wanted him to be part of her camp, not that of her husband. As a devotee of mystic rituals she honoured the gods on a daily basis, a practice emulated by her son. Consequently, Alexander grew up profoundly religious, primed to believe in the manifestation of gods in many cults and places. Steeped in Homer, he lived in a world of Greek heroes and gods. Throughout his life he would always be looking for divine signs to lead him on his way; and Dionysian rites in particular fascinated him, a result of his mother’s influence.

Alexander’s religious interest was fuelled by Olympias’s stories (told out of spite when her relationship with Philip began to deteriorate) that his true father was not Philip but Zeus, king of the gods, a tale that spoke to the imagination of the young boy. Later, Alexander traced his ancestry to the demi-god Heracles, the most popular of Greek heroes. Heracles was famous for his extraordinary strength and courage, as demonstrated in his performance of twelve arduous labours, including the killing of the Nemean lion.

Education

Compared to the Macedonian traditions of his day, Alexander received a highly sophisticated education. Until the age of thirteen he stayed at home, initially under the care of his nurse, Lanice (sister of Cleitus the Black, the commander of the royal squadron of the Companion Cavalry). Then, at the age of seven, he stepped out from under her wing to undergo rigorous training by Leonidas, a relative of Olympias. This kinsman taught him the physical skills needed for being a warrior king—skills such as horse riding and sword fighting. Contemporaries of Alexander tell that the youth displayed great aptitude for sports and combat. He also learned the virtues of self-control and self-denial during this early stage (Arrian, 1971; Bosworth, 1988).

Stern, petty, and controlling, Leonidas was in the habit of searching Alexander’s possessions to ensure that Olympias had not smuggled any luxuries to her son. Spoiling children was not part of his educational programme. He instilled in Alexander the ascetic nature for which he became famous during his future campaigns: for much of his short adult life he would live spartanly, eating and sleeping together with his troops.

During Alexander’s training with Leonidas, the young prince is said to have extravagantly thrown two fistfuls of incense on the altar fire during a religious ceremony. Leonidas, so the story goes, chided him, saying, “When you have conquered the spice-bearing regions, you can throw away all the incense you like. Till then, do not waste it” (Plutarch, 1973, p. 281). That admonition stuck with the young man. Many years later, after he captured Gaza, the main spice depot for the whole Middle East, Alexander sent Leonidas eighteen tons of frankincense and myrrh with the admonition not to be so stingy towards the gods (Green, 1991; Plutarch, 1973).

During his early military training, Alexander was also taught by the courtier Lysimachus, a person with very different interests from those of Leonidas. Lysimachus helped Alexander appreciate the arts and taught him to play the lyre. Lysimachus was much beloved by Alexander and liked to call himself Phoenix to Alexander’s Achilles. Later in life, encouraged by his teacher, Alexander would be a great patron of musicians, actors, painters, writers, and architects.

Because of Lysimachus’s influence, Alexander is said to have known the writings of Homer and Euripides by heart. He had a great love for Homer’s epic sagas and was inspired by the mighty deeds of the gods and heroes during the Trojan War. He always slept with a copy of the Iliad under his pillow. His favourite line from Homer is said to have been, “Ever to be the best and stand far above all others.” His favourite role model was the Iliad’s Achilles (in part, presumably, because of the assumed familial link).

As portrayed in works of antiquity, even as a young boy Alexander was fearless, strong, tempestuous, and eager to learn. Father and son were both extremely ambitious and highly competitive. Alexander was like a racehorse, eager to emulate and then surpass the conquests of his father. As a youngster, he is said to have complained to his friends, “My father will forestall me in everything. There will be nothing great or spectacular for you and me to show the world” (Plutarch, 1973, p. 256). In spite of the spirit of competition between the two of them, however, Philip was immensely proud of his precocious son—at least initially.

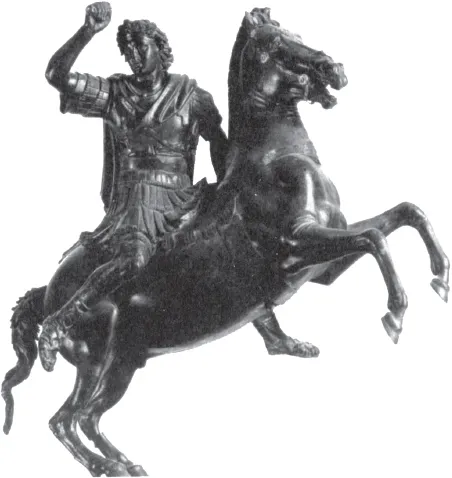

At the age of twelve, Alexander tamed the beautiful and spirited Bucephalus (meaning “ox-head” in Greek), a horse that no one else (including his father) was courageous enough to ride. Always ready for a dare, and compelled to compete with his father, he made a wager that he would be able to ride the horse. His father—who feared for his son’s life when he tried to tame the stallion—is said to have wept for joy when the boy returned triumphantly seated on the horse. After this feat his father allegedly said, “You must find a kingdom big enough for your ambitions. Macedonia is too small for you” (Plutarch, 1973, p. 258). Eventually, this famous stallion carried him as far the Hydaspes River in India, where the mount died. In sorrow, Alexander built the city of Bucephala, in memory of his beloved horse.

As time passed, Alexander’s relationship with his father became increasingly discordant. When his father began to slight his mother, Alexander clung to the fantasy that Philip was not his real father, that he had a more regal ancestry as a child of the gods. Olympias fed this fantasy and also encouraged Alexander to think of himself as a king in his own right, not merely a successor to Philip. This frame of mind, and the behaviours it engendered, led to many father-son quarrels.

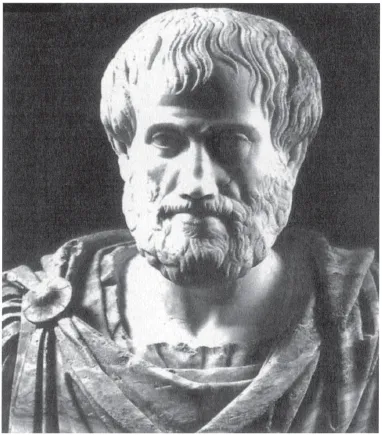

When Alexander reached the age of thirteen, his father felt that it was time for the young man to move on to higher education. King Philip chose the still relatively unknown philosopher Aristotle to work with his son. For three years Alexander and the other boys of the Macedonian aristocracy (known collectively as the School of Pages) were taught by Aristotle at the Mieza temple, about thirty kilometres from the royal palace at Pella. Among this select group of aristocrats were his lifelong friend and lover Hephaestion, Cassander, son of the general Antipater, and Ptolemy, the two last being themselves future kings.

In this “miniature Academy” Aristotle introduced Alexander to the world of arts and sciences. Alexander developed a great aptitude for debate, rhetoric, and drama during these years, becoming a gifted orator who could tailor his message to any situation (a faculty that would be extremely helpful later, when he led his troops). His tutor also stimulated his passion for scientific exploration and discovery. Due to the influence of Aristotle, Alexander developed a strong interest in medicine, botany, and zoology. Later, his knowledge of medicine would stand him in good stead, lending understanding to his concern for his soldiers’ wounds and sicknesses.

In addition, Aristotle’s political teachings provided Alexander with a solid background in law and statecraft, profoundly influencing the young prince and preparing him for the administration of his later empire. Aristotle wrote the treatise On Kingship (a document that has not survived the centuries) to help Alexander understand his responsibilities. The philosopher’s image of the philosopher-king gave the future king a role model he could emulate. As Aristotle conquered the world with thought, he taught the young man who would conquer the world with the sword (Aristotle, 1988).

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Table of Contents

- List of Illustrations

- About the Authors

- Preface

- Introduction

- Part I: Histiography

- Part II: Leadership

- Notes

- References

- Index