- 292 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

"An indispensable tool for college students and general readers, the only available text that treats Vietnamese history in its entirety, from its beginning to the twenty-first century, as it places Vietnam within the regional and global context. SarDesai's Vietnam looks at Vietnam as a country and not just as a war. The text has also benefited from its author's decades-long expertise on Southeast Asia as reflected in the comprehensive bibliography and use of the latest works." —NGUYEN THI DIEU, Ph.D., Temple University

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Vietnam by D.R. SarDesai in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Politics & International Relations & Asian Politics. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

CHAPTER 1

Ethnicity, Geography, and Early History

The Southeast Asian littoral, the promontory at the extremity of mainland Southeast Asia, constitutes Vietnam. It extends from about 8° to 23°N and 102° to 109°E. The long coastline of Vietnam uncoils in the shape of an S from China's southern border to the tip of the Indochina Peninsula. It is bordered on the north by China, to the west by Laos and Cambodia, and to the east and south by the South China Sea. Nearly 1,240 miles long, the country extends unevenly at widths ranging from 31 to 310 miles and covers an area of 127,300 square miles. Vietnam is as large as the British Isles, smaller than Thailand, with a population estimated at 79 million in 2004, making it the thirteenth largest populated country in the world. Owing to heavy human losses during the long conflict, the population is young, with 70 percent under the age of thirty. The literacy rate is one of the highest in the world; 90 percent of those age ten and over are literates.

Vietnam's two fertile alluvial deltas—the Red River, or Song Ma, in the north and the Mekong in the south—have inspired the image of the typical Vietnamese peasant carrying a pair of rice baskets suspended at the ends of a pole. Connected by a chain of narrow coastal plains, the deltas produced enough rice before the war not only to feed the population but even to export. Since the late 1990s, Vietnam has become the second largest exporter of rice in the world. Although these delta regions make up only about a quarter of the country's area, they support almost 80 percent of its population. The rural population density in some of the provinces of the Red River Delta is as high as 1,000 per square mile. The Mekong Delta is the richer of the two and extends well into Cambodia. Both deltas are known for their intensive agriculture; the Red River Delta has long reached the point of optimum agricultural expansion. The country's historical, political, and economic development has taken place in these two separate areas partly because of a mountain range dividing the country. The Truong Son, or Annamite Cordillera, runs approximately north and south along the border of Laos and Vietnam, cutting the latter almost in two and also extending along the Vietnamese-Cambodian border. At certain points, the mountains have elevations of up to 10,000 feet.

Communications between Vietnam and Laos or Cambodia are possible through certain strategic passes. Of these, the more difficult ones are located in the north at an altitude of more than 3,000 feet at the head of the valleys of the Song Da (Black River), the Song Ma (Red River), and the Song Ca. Further south the communications are, by comparison, not as difficult. Thus the Tran Ninh area can be reached through the town of Cua Rao, whereas the Cammon Plateau can be reached from the Nghe An area through the Ha-trai and Keo Nua Passes at an altitude of more than 2,000 feet or further south through the Mu Gia Pass at a somewhat lower altitude. From Quang Tri one can traverse just north of the Kemmarat rapids through the Ai Lao Pass (at an altitude of about 1,300 feet), regarded as the gateway to Laos. Between the Red River Delta and central Vietnam, communications go through several passes and corniches at Hoanh Son, the gateway to Annam, at elevations of between 1,300 and 1,500 feet. The geographical configuration and the varied accesses are extremely significant for understanding the movement of people and armies in the military encounters in ancient as well as recent times.

Vietnam—The Nomenclature

For most of their history, the Vietnamese people lived only in the Red River Delta. During the first millennium of the Christian era, from 111 BC to AD 939, Vietnam was a directly ruled province of the Chinese empire. The separate kingdom of Champa, south of the empire's border in central Vietnam, existed until 1471, when most of it was overrun by independent Vietnam. The remnant of Champa was absorbed by the Vietnamese in 1720. Thereafter, taking advantage of an extremely weakened Khmer empire, the Vietnamese gradually expanded into the Mekong Delta, completing the conquest by the middle of the eighteenth century and reaching the modern borders of Vietnam.

Vietnam has had a succession of names, reflecting its rule by various people at various times. The Chinese called the country Nan Yueh and the Red River Delta the Giao. In the seventh century, after putting down a series of revolts by the Vietnamese, the Chinese renamed the territory Annam, meaning "pacified south." After the Vietnamese overthrew the direct Chinese rule in AD 939, the kingdom was called Dai Co Viet (country of the great Viet people). Through the centuries, as Vietnamese rulers extended the kingdom almost to the present-day borders, the three natural divisions of Vietnam— north, central, and south—came to be known to the Vietnamese as Bac Viet, Trung Viet, and Nam Viet, respectively. The kingdom as it existed in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries covering north and central Vietnam was divided into two political parts and ruled by two families: the Trinh in the north and the Nguyen in central Vietnam, both of whom recognized the Le as kings (see chapter 2). The country was unified for the first time by Emperor Gia Long in 1802 and was named Vietnam. Because France conquered Vietnam in three different stages and later tried through official policies to submerge the nationalist identity and spirit of the Vietnamese people, the French referred to the three regions only by the names of their administrative units, insisting also that these corresponded to three separate cultural entities. Cochin China in the south was a French colony; Annam, or central Vietnam, with its imperial capital of Hue, was a protectorate; and Tongking, with Hanoi as capital, was regarded as a separate protectorate. The French vivisection of Vietnam was regarded as an insult by Vietnamese nationalists, who vowed to liberate their country from the French (and later from the Americans) and to bring about its reunification as the single nation-state of Vietnam. This they accomplished in 1976, after a relentless struggle lasting several decades.

The Human Fabric and Languages

The Vietnamese

The Vietnamese, who form 85 percent of the population, are a mixture of non-Chinese Mongolian and Austro-Indonesian stock who inhabited the provinces of Kweichow, Kwangsi, and Kwantung before the area was brought under Chinese rule in 214 BC. Further racial intermixture probably came about through marriages between the Vietnamese and a Tai tribe long after the Vietnamese had moved into the Tongking Delta.

The mixed racial descent of the Vietnamese is reflected in their language, which is both monotonic like the Malayo-Indonesian and variotonic like the Mongolian group of languages. It is also influenced by the Mon-Khmer languages in its grammar (no declension or inflection) and even more so in its vocabulary (up to 90 percent of words in everyday usage). Vietnamese owes its multitonic system as well as a large number of words to the Thai language. By the time the Vietnamese came under Chinese rule in 111 BC, they already had a well-developed language of their own. Thereafter, the monosyllabic Vietnamese language drew heavily on the Chinese for administrative, technical, and literary terms. For most of their history, the Vietnamese used Chinese ideographs for writing. In the twelfth century, the Vietnamese developed the Nom characters (literally meaning southern characters) independent of the Chinese. In the seventeenth century, a Jesuit missionary, Alexandre de Rhodes, developed a romanized system of writing. Quoc-ngu, as it is called, shows the differing levels of pitch as well as vocal consonant elements by diacritical marks. It was widely adopted for common use in the twentieth century.

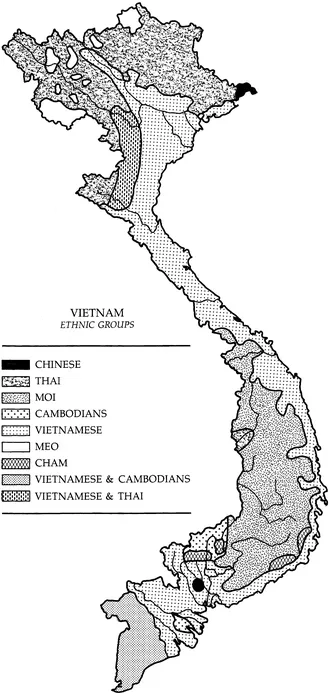

The Tribals

Several tribal groups live in the extensive mountainous country to the north and west of the Red River Delta. The Meo, the Muong, and the Tai, all of Mongolian origin, are the most important and numerous. Together, all the tribals account for about 2 million people. The Tai speak languages closely allied to those of Thailand and Laos. Except for the 20,000 Muong, who use a language akin to Vietnamese, the other tribes speak dialects of Tibeto-Mongolian origin. The vast plateau and hilly areas of central Vietnam are inhabited by several ethnic minorities numbering nearly 1 million people and collectively called the Montagnards by the French. Six of the larger groups account for nearly half of the tribal population. These are the Rhade, Sedang, Jarai, Stieng, Bahnar, and Roglai, certainly a heterogeneous people, whose skin color ranges from brownish white to black and whose languages are drawn both from the Malay-Polynesian and the Mon-Khmer groups. They were pushed into the mountains by the Vietnamese moving south.

Traditionally, there is not much love lost between the tribal people and the plains people. Renowned as warriors and as masters of the strategic passes, the tribals have been able to move swiftly across the borders of Vietnam into Laos and Cambodia. They may be fewer in number than the Vietnamese and their weapons far less sophisticated, yet they were never completely subdued by the Vietnamese. Due to their bravery, skills, and knowledge of the terrain, the tribals were wooed by the Chinese as they considered an invasion of Vietnam, later by the French, and by both sides in the recent drawn-out war. The tribals have held all outsiders, including the ethnic Vietnamese, in contempt and have viewed them with strong suspicion. They do not have the Vietnamese enthusiasm for wet rice cultivation, preferring instead to burn the brush on the mountain slopes and resort to dry rice cultivation. Their ways of life, languages, dress, social organization, and house structures have all been distinct from those of the Vietnamese. Generally speaking, the Montagnards have never displayed a high regard for the law and government of the plains people.

Vietnam's Ethnic Groups

Despite governmental efforts to better their lot, the tribal population of Vietnam still follows primitive ways of life, eking out a miserable existence exploiting the infertile and inhospitable terrain constituting four-fifths of the country's area. After 1954, the North Vietnamese government introduced several programs to improve their economic condition. This was perhaps because of the valuable assistance the tribals gave to the Viet Minh, who had operated from their hideouts in the mountainous territory of the northwest during the struggle against the French. The present government of Vietnam has a twofold policy toward the tribal population. On the one hand, it allows them autonomy, thus helping them to maintain their ethnic identity through retention of age-old social institutions and practices. On the other hand, it encourages assimilation through education and common participation in the life of the lowlands.

The Chams

Also in central Vietnam are the Chams, numbering about 40,000. The descendants of a former dominant and highly civilized people who controlled central Vietnam for nearly fifteen centuries, they are of Indonesian stock and have reverted to a tribal lifestyle. Their former kingdom, called Champa (or Linyi in Chinese records), was founded in AD 192 by a local official who overthrew the Chinese authority. Taking advantage of the weak Chinese control over Tong-king in the declining days of the Han dynasty, the Chams extended northward. Although they controlled portions of central Vietnam at various times, Champa proper extended from a little south of Hueéto the Cam Ranh Bay and westward into the Mekong valley of Cambodia and southern Laos. The history of the relationship between China and Champa was one of alternating hostility and subservience on Champa's part. With the reconsolidation of China under the Chin dynasty, Champa sent the first embassy to the Chinese emperor's court in AD 284. But whenever the Chinese authority in Tongking slackened, the Chams seized the opportunity to raid the northern province. During this early period, the center of the Champa kingdom was in the region of Hué.

Champa came under Indian influence around the middle of the fourth century AD, when it absorbed the Funanese province of Panduranga (modern Phan Rang). Funan was an early kingdom based in Cambodia, extending its authority over the Mekong Delta, southern Laos, Cambodia, and Thailand from about the first century AD. The political center of Champa had by then moved from near Hué to the Quang Nam area, where the famous Cham archaeological sites of Tra Kieu and Dong Duong indicate the profound Pallava impact of the Amaravati school of art. In the same area, the most notable archaeological site is that of My-son, a holy city whose art demonstrates Gupta influence as well as that of the indigenous pre-Khmer concepts of Cambodia. After the sixth century, the center of Cham activity moved south to Panduranga, where the south Indian influence increased, as is seen, for instance, in the towers of Hoalai, In the opinion of the eminent French scholar Georges Coedes, it was the Indianization of Champa that lent it strength against its Sino-Vietnamese enemies.1

Although the kingdom was divided into several units separated from each other by mountains, the Chams rallied dozens of times in the defense of freedom against attacks by the Chinese, the Vietnamese, the Khmers, and, later, the Mongols. In such conflicts Champa's mountainous terrain and easy access to the sea provided considerable scope for military maneuver. At last, after a millennium and a half of survival as an independent state, the Chams suffered a severe defeat at the hands of the Vietnamese in 1471. More than 60,000 Chams were killed and about half that number were carried into captivity. Thereafter, Champa was limited to the small area south of Cape Varella around Nha Trang. The remnant state lingered until 1720, when it was finally absorbed by the Vietnamese, the last Cham king and most of his subjects fleeing into Cambodia.

The Cham society was and is matriarchal, daughters having the right of inheritance. Following the Hindu tradition, the Chams cremated their dead, collected the ashes in an urn, and cast them into the waters. Their way of life resembled that of the Funanese. Men and women wrapped a length of cloth around their waists and mostly went barefoot. Their weapons included bows, arrows, sabers, lances, and crossbows of bamboo. Their musical instruments included flutes, drums, conches, and stringed instruments. Today about 40,000 southern Vietnamese and about 85,000 Cambodians claim Cham ancestry. Their social organization, marriage, and inheritance rules did not change despite their later conversion to Islam.

The Khmers

Not far west of Saigon and south of the Mekong live about 500,000 Khmers in what were once provinces of the Khmer empire (founded in the ninth century AD) and its precursors, the kingdoms of Chenla (seventh to eighth century AD) and Funan (first to sixth century AD). Like the Chams, the Funanese were of Indonesian race, whereas the Chenlas and the Khmers were kindred to the Mons of Burma. At its height, the Khmer empire extended over the southern areas of mainland Southeast Asia, including the Mekong Delta. The Funanese and the Khmers were extremely active as a maritime commercial power, serving as intermediaries in the trade between India and China. Both were Indian ized kingdoms that adopted the Sanskrit language and Indian literature and religions and grafted Indian concepts of art and architecture to indigenous forms, producing (among others) the world-renowned monuments of Angkor, After the sack of Angkor by the Tais in AD 1431, the Khmers became subservient to the Tais but still retained control of the Mekong Delta. With the Vietnamese conquest of Champa and the final absorption of the Champa kingdom, the Mekong Delta region of the Khmer kingdom was exposed to the aggressive Vietnamese policies. The present-day Khmers of Vietnam are descendants of the population that chose to stay on in the Mekong Delta after its conquest by the Vietnamese in the eighteenth century. An indeterminately large number of them were used by the Vietnamese as an advance column in their march into Cambodia in December 1978.

The Chinese

Until the recent exodus, there were more than a million Chinese in Vietnam, mostly in the south and especially in Cholon, the twin city of Saigon (now called Ho Chi Minh City). Some of them are descendants of very old families, whereas ancestors of most others migrated in the wake of the French colonial rule in the nineteenth century, principally from the Canton area. As in most other countries of Southeast Asia, the Chinese dominated the economic life of their adopted country, acting as traders, bankers, moneylenders, officials, and professionals. They maintained close ties with relatives in their homeland. Due to their economic power, they invited the hatred and distrust of the Vietnamese people and governments, including the present Communist government. More recently, they became the target of official persecution in 1978-1979, resulting in their large-scale migration to China and as boat people to other destinations. A large number perished on the high seas.

One of the most persistent themes throughout Vietnamese history is a love-hate relationship between China and Vietnam. If the Vietnamese appreciated, admired, and adopted Chinese culture, they despised, dreaded, and rejected Chinese political domination. Such a mixture of envy and hostility is seen in the contemporary Vietnamese attitudes toward the ethnic Chinese in Vietnam, who have been by far superior to the Vietnamese in trade, commerce, and finance. Historically, Vietnam was the only country in all of Southeast Asia with close political and cultural ties to China, all the other Southeast Asian countries being heavily influenced by Indian culture, at least in the first millennium of the Christian era. As David Marr observed, "The subtle interplay of resistance and dependence ... appeared often to stand at the root of historical Vietnamese attitudes toward the Chinese."2

The long history of Sino-Vietnamese relations was marked by significant Vietnamese absorption of Chinese culture both through imposition and willful adoption. Vietnamese intellectuals through the centuries have regarded their country as the "smaller dragon" and a cultural offshoot of China. Nonetheless, their history has been punctuated by numerous valiant efforts to resist the deadly domination of their land by their northern neighbors. Vietnamese nationalism has taken a virulent form whenever fear of Chinese takeover loo...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title

- Copyright

- Dedication

- Contents

- List of Tables and Maps

- List of Acronyms

- Preface

- 1 ETHNICITY, GEOGRAPHY, AND EARLY HISTORY

- 2 A MILLENNIUM OF FREEDOM

- 3 THE FRENCH CONQUEST OF VIETNAM

- 4 THE NATIONALIST MOVEMENT

- 5 ROOTS OF THE SECOND INDOCHINA WAR

- 6 THE INDOCHINA IMBROGLIO

- 7 THE NEW VIETNAM

- 8 VIETNAM AND ITS IMMEDIATE NEIGHBORS

- 9 VIETNAM'S RELATIONS WITH CHINA, THE SOVIET UNION, AND ASEAN

- 10 US-VIETNAM RELATIONS AND VIETNAMESE AMERICANS

- Chronology

- Notes

- Bibliography

- Index