- 204 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

University Architecture

About this book

Some of the most exciting architecture in the world can be found on university campuses. In Europe, America and the Far East, vice chancellors and their architects have, over several centuries, produced an extraordinary range of innovative buildings. This book has been written to highlight the importance of university architecture. It is intended as a guide to designers, to those who manage the estate we call the campus, and as an inspiration to students and academic staff. With nearly 40 per cent of school leavers attending university, the campus can influence the outlook of tomorrow's decision makers to the benefit of architecture and society at large.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

Part one

The campus

CHAPTER 1

Academic mission and campus planning

Defining a university: the challenge of design

A university may be defined as a self-governing, mainly publicly funded, community of academics and students engaged in absorbing, advancing or disseminating knowledge. Normally a university occupies a well defined physical area, giving it a sense of identity and social focus. There are exceptions, such as the UK’s Open University, which relies upon electronic media and summer schools for communicating with students engaged in academic discourse, but generally buildings make a university in both functional and spiritual terms. Since universities are diverse communities of scholars engaged in collective pursuit of knowledge, it is normally necessary to express the academic character of different institutions in built form and spatial pattern. Reinforcing the high ideals of learning through the physical fabric gives architects the opportunity to experiment or innovate. Historically, and particularly over the past fifty years, some of the most challenging and original works of architecture have been for university clients.

1.1 The University of East Anglia, Norwich, UK, has been an important centre for architectural experiment since its foundation in 1965.

Whereas vice-chancellors are keen to express the mission of their university in built form, or the matrix of spaces created, visionary architects are also drawn to the arena of the universities by the climate of invention fostered by academic ideals. Two examples illustrate the argument – Le Corbusier’s Carpenter Fine Arts Center at Harvard University (1959–63) and James Stirling’s History Faculty Building at Cambridge University (1965–7). Both were for well-established universities and led to buildings of great symbolic weight and volumetric invention constructed within highly conservative physical environments, and each in different ways became the focus for heated debate among academics. The need for new buildings to express or challenge values beyond the utilitarian is arguably the distinguishing feature of the best of university architecture.

1.2 Engineering Building, Leicester University, UK, by James Stirling (1965).

Universities in worn out cities are a symbol of physical and intellectual renewal. New universities constructed in emerging countries serve a similar spiritual function. Though constructed of concrete, steel and glass, a university is more easily defined in academic than social or architectural terms. We know that universities have high standards of governance and scholarship but these ideals are not always translated into physical environments. One of the best measures of a university is whether it looks like a centre of higher education. Such criteria transcend function and address questions of meaning and identity. This is dangerous territory for chancellors and designers alike, but for a university to fully fulfil its mission, the fabric of education (both buildings and spaces) needs to reflect academic aspirations. A university committed to testing and applying new skills or knowledge should embrace these within the built estate. New concepts in education lead to environments of innovation.

Universities are places of teaching and learning. They generate a feeling of community in whole and in part. The role of colleges is to create small, self-regulating units of resdential scholars who share dining and other social spaces. Sometimes the challenge is not so much that of establishing a distinct character for a college but for a faulty. Here a group of buildings or a single large one may require its own identity in order to reinforce the sense of a distinctive academic community. The administrative structure of a university, whether it be by faculties or colleges (or a combination) provides a framework for architectural expression. The hierarchies of built form, the spatial pattern of campus parts, the order of connection and much else needs to reflect the mission and organisation of the university in the widest sense. Where a university masterplan is based upon flexibility in the assembly of buildings it can lead to loss of environmental distinctiveness and the breakdown of a sense of place for faculties.

The speed of change in research and learning puts great stress upon the notion of academic community. The places created for learning become themselves stressed by the forces of change released by that learning. The striving for innovation in research, scholarship and teaching which universities promulgate creates a momentum of instability which highlights the limit of buildings to contain the activities within them. More than most building types, university teaching departments or research centres are less forms which follow function than those which struggle to contain dynamic uses.

If the speed of change is such that stability of form and function is only achieved for short periods, how then is reconciliation with the feeling of community to be achieved? The answer lies in distinguishing between building types and, in the buildings themselves, between rapid change and permanent elements. Halls of residence are less subject to unpredictable change than research laboratories, for example, and processional or ceremonial spaces (senate room, graduation hall) are less stressed by innovation than teaching or seminar rooms. Handling the forces of change within buildings requires a distinction to be made between the various elements of construction so that parts can be replaced or changed without distorting the whole. For instance, the main structural grid of columns should be free of walls, the walls unencumbered by built-in services, the power supplies free to change without great disruption to finishes and so on. It is an approach to design which gives physical and spatial clarity to the parts, which accepts orders or timescales of change, which allows for the unpredictable at the design stage, and which accepts that the logic of maintenance should influence design.

1.3 Planning principles, Stanford University, Palo Alto, USA.

The degree of change is a measure of the vitality of a university. Institutions which are not perpetually disfigured by tower cranes and construction plants may not be evolving to meet new student demands. Internal change can only meet some of the fresh functions required of educational innovation. Often functional innovation expresses itself in extensions to existing buildings. Research laboratories may have to be expanded to provide space for new scientific processes; successful faculties require additional teaching space; the notion of student-centred learning changes the use, form and content of libraries. Inevitably, academic change is expressed in the fabric of the university and the need to accommodate unpredictable, spasmodic and often rapid change is a frequent requirement of design briefs. The university masterplan has somehow to create a feeling of community among students and lecturers yet provide the means to accommodate change without disruption. The two factors – flexibility and order – are often in conflict. Cementing the sense of collegiate character requires physical identity and spatial enclosure. Traditionally the college was expressed through the vehicle of the courtyard, more recently the university was built around a processional street or linked squares – London University is a good example of connected squares of learning and Harvard of a pattern of processional streets. In both cases physical enclosure by buildings is the means by which social space is defined. Yet external space is just what expansion and change requires. Just as within buildings space is the means of accommodating flexibility, the same is true of the external environment. Space is required around the perimeter of buildings to meet the relentless pressure for growth on the university campus but to provide such space at the outset undermines the creation of physical enclosure which is the main means by which collegiate character is imparted.

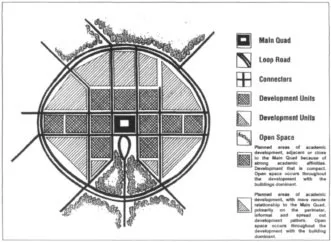

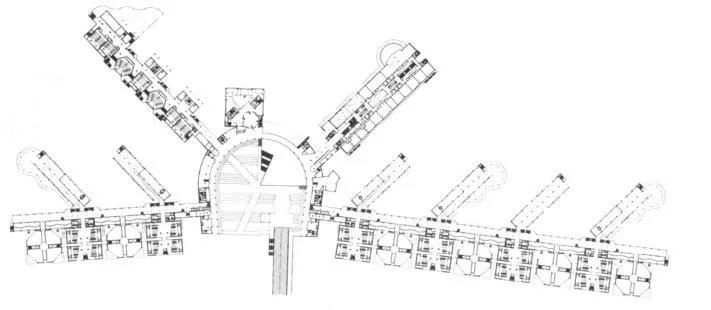

1.4 Legibility and extendibility combined at Temasek Polytechnic, Singapore, by Michael Wilford and Partners.

There are models of successful campus masterplans which create a sense of place and accommodate change. Michael Wilford’s radially ordered masterplan for Temasek Polytechnic, Singapore (1994), cleverly distinguishes between permanent and less permanent parts, creating space for expansion in a fashion which does not destroy the campus core or undermine teaching territories. The academic centre is well defined in volumetric and external space terms, the linear expansion of different teaching areas can be readily achieved, and the research areas can be altered or redeveloped without great disruption to the remainder. In addition, the campus has a unifying sense of landscape, an order which is planted rather than built, and which addresses the need for reflection within education.

The sense of place helps universities market themselves to potential students. In the competitive world of higher education, architectural quality matters. As students generally visit different universities before making their final choice, the visual impact of the campus is vital. The quality of environment is seen as an important selling point for universities judging by the images used in university prospecti. Most show students busying themselves against a backcloth of modern buildings and friendly external spaces. Some prospecti also show off the latest buildings by fashionable architects (Thames Valley University with its new library by the Richard Rogers Partnership) in the hope of attracting students to the campus.

The marketing of universities through design provides a further justification for the pursuit of architectural quality. If the university does not project a positive image of itself through its built fabric, it is unlikely to attract the best students. Since many universities supplement their income by hosting conferences or attracting business clients, the character of the campus has economic significance here as well. As universities become increasingly business orientated, marketing through architectural image helps raise awareness of the economic value of good design.

1.5 Architectural image can help promote a new university. Paul Hamlyn Learning Resource Centre, Thames Valley University, Slough, UK, by Richard Rogers Partnership.

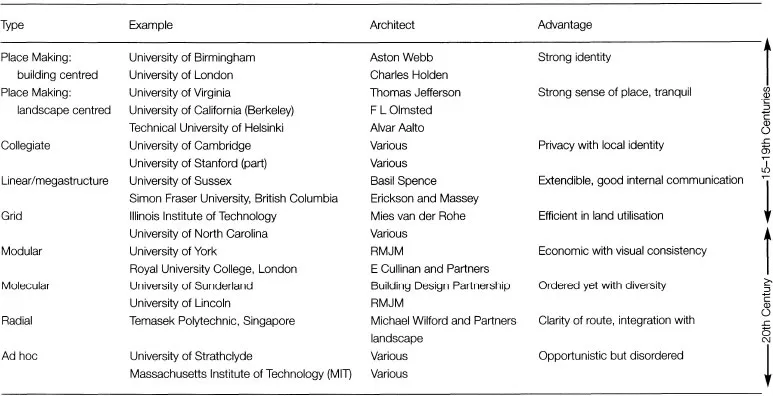

Table 1.1 Types of University Campus

Universities are not only a dialogue between academic image and built form in the widest sense, they are also engaged in a discourse with time and space, or, put another way, with history and geography. History shapes cultural awareness and this, with many nations, is an important factor in determining the layout and detailed planning of universities. A good example is the new university at Qatar, which blends modernity in the form of rectangular buildings with elements of Islamic culture. The campus, designed by Kamal El Kafrawi, has two separate social worlds for male and female students while allowing full intellectual interaction in the lecture t...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Half Title page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Contents

- Acknowledgements

- Introduction

- Part One The campus

- Part Two Buildings

- Part Three Conclusions

- Bibliography

- Index

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access University Architecture by Brian Edwards in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Architecture & Architecture General. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.