- 496 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

This book introduces the first champions of the cause of charity toward the sick and wounded: the Genevan philanthropists and physicians. It focuses on the international Red Cross movement from the first Geneva conference in 1863 until the Tenth Conference in 1921.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Champions Of Charity by John Hutchinson in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & World History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Part One

The Civilizing Mission

There’s nothing wrong with war except the fighting.

—Evelyn Waugh, Unconditional Surrender (1961)

1

A Happy Coincidence

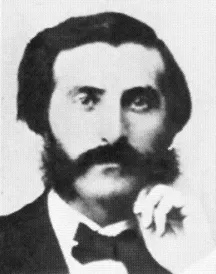

ONE DAY IN 1862, Genevan philanthropist Gustave Moynier received in the mail a small book entitled A Memory of Solferino. Moynier knew nothing of its author, a young businessman named Henry Dunant, but as president of the Geneva Society for Public Utility (SGUP) he was used to being approached with requests to support various good causes. On reading this book, he discovered that Dunant’s cause was that of caring for wounded soldiers. The author, it seemed, had been an involuntary witness to the human carnage caused by the battle of Solferino in 1859, when French and Sardinian armies fighting to liberate Lombardy from Austrian rule had clashed with the armies of Emperor Francis Joseph. Moynier read with growing interest and concern Dunant’s harrowing descriptions of soldiers grievously wounded and then seemingly abandoned to a gruesome fate by armies that lacked sufficient doctors, nurses, dressings, and field hospitals to care for them properly. In a few paragraphs at the end of the book, Dunant appealed to his readers to take up the cause of the war wounded by promoting the formation of voluntary aid societies that could furnish supplies and trained nurses to remedy the deficiencies of the official army medical services.

Thinking this a cause worthy of support, Moynier asked Dunant to call on him to discuss what plans the young author had made to bring the proposed aid societies into being. Apart from having his book printed at his own expense and having sent it around Europe to influential persons such as Moynier himself, Dunant had done nothing; as he had written in A Memory of Solferino, he hoped that his book would “attract the attention of the humane and philanthropically inclined.”1 Moynier, quickly sizing up Dunant as an idealist rather than an organizer, offered to help; he would be happy, he said, to raise the subject of voluntary aid societies at the next meeting of the SGUP, in order to gauge by the reaction of its members—all of them men of affairs—whether such a proposal was feasible and worth pursuing further. Delighted by this promise of support Dunant took his leave, convinced that his cause would find immediate and unwavering sympathy among everyone who heard about it. The more practical Moynier, meanwhile, began to wonder whether men who knew more about armies and medicine than himself or Dunant would be to the idea.

Two more unlikely collaborators than Dunant and Moynier could scarcely have been imagined. On the face of it, they shared a good deal: Genevan upbringing, respectable bourgeois backgrounds, the Protestant religion, and a desire to improve the lot of suffering humanity. Yet they were as different in their temperaments as they were in their ideas of how to achieve this goal. The impulsive Dunant was a fervent evangelical Christian who, like an Old Testament prophet, sought to bring himself and others closer to God through acts of repentance and contrition; Moynier, on the other hand, was an austere and high-minded Calvinist who had found in utilitarian philanthropy the path to a new moral world of rationality, sobriety, and self-discipline. Their collaboration would be brief, awkward, even strained; for each soon found the other extremely difficult to work with.

However, their first meeting was one from which, “by a happy coincidence,” as Moynier later put it, momentous consequences were to flow.2 The coincidence lay in the fact that the 1860s happened to be a decade when the European powers—for their own good reasons—were prepared to give some attention, in a concerted way, to the care of wounded soldiers. In these peculiarly favorable circumstances, Moynier and Dunant were able to influence, in their very different ways, both the birth of the Red Cross and the signing of the Geneva Convention. Because of this happy coincidence—and only because of it—Moynier’s interview with Dunant became a memorable event in the history of both war and charity.

Dunant and Solferino

Henry Dunant was a devotee of Christian pietist philanthropy. He was raised in a family that had been heavily involved in the religious revival that swept Geneva after the turmoil of the Revolutionary and Napoleonic Wars. An enthusiastic volunteer even as a youth, Dunant had joined a charitable society whose members visited and gave small allowances to the city’s poor and sick and distributed moral tracts to prisoners.3 He was also a promoter of the “Christian Unions” that appeared in France in the 1850s, organizations that have been regarded as the forerunners of the Young Men’s Christian Association. Dunant took his religion very seriously and very personally. When he sat down to write about what had happened at Solferino, he later confessed, he believed himself to be an instrument of God: “I was as it were, lifted out of myself, compelled by some higher power and inspired by the breath of God. … In this state of pent-up emotion which filled my heart, I was aware of an intuition, vague and yet profound, that my work was an instrument of His Will; it seemed to me that I had to accomplish it as a sacred duty and that it was destined to have fruits of infinite consequence for mankind. This conviction drove me on.”4

1.1 Henry Dunant, author of A Memory of Solferino.

1.2 Genevan philanthropist Gustave Moynier was the real architect of the Red Cross, although in the twentieth century members of the movement have, for their own reasons, preferred to accord this role to Henry Dunant.

Dunant’s notion that he had been chosen to accomplish a divine mission attracted to his cause those who wanted to believe in him; for more practical souls such as Moynier, this belief in divine inspiration was one of the things that made Dunant a difficult collaborator.

It was, however, not evangelical religion but business that had taken Dunant to Lombardy in the summer of 1859. He was, in fact, searching for Napoleon III, in the hope that an appeal to the sovereign himself could cut through the red tape that threatened to block a business deal in which Dunant was involved in French Algeria. The details of the enterprise may be passed over; what matters is that Dunant, anxious to overcome these bureaucratic obstacles, had gone to Paris to find the emperor but had been told that Napoleon III was already on his way to Piedmont.5 Dunant was disappointed, not least because he had hoped to present the emperor with two of his writings, one a memorandum concerning his Algerian company (the Société anonyme des Moulins de Mons-Djémila) and the other a tract on the reestablishment of Charlemagne’s empire by Napoleon III—an extraordinary piece of pseudoreligious nonsense in which Dunant claimed that the restoration of the Holy Roman Empire had been foretold in the Book of Daniel.6 Swallowing his disappointment, Dunant set out for Italy in the hope of tracking down the emperor. Thus it was that he happened upon the scene of the battle of Solferino on 24 June to find the many wounded from both armies who had been brought to an improvised field hospital in the church building and churchyard of nearby Castiglione.

Appalled by the plight of so many untended wounded soldiers, Dunant forgot the purpose of his trip and spent several days doing what he could to relieve their misery. In the absence of adequate supplies, this often meant simply comforting them or saying a prayer because there was little water available to clean a wound or relieve parched lips. Only after he had done everything he could for the wounded did he proceed to the encampment of the French army to resume his search for the emperor. There were others in Castiglione as well—many local women, an Italian priest, a journalist from Paris, a couple of English tourists—but it is Dunant’s perception of these terrible days that has survived in A Memory of Solferino. He was far too busy on the days in question to keep a diary, so the book was composed from memory two or three years after the event. Despite this, it is as vivid and immediate as if it had been written at the time; reading it, one can easily believe that Dunant was driven to write it by the nightmare visions that must have stayed with him after such an experience.

So much hagiography has been written about this man and his book that both have been seriously distorted. The reality is that Dunant was as impressed by the sight of armies in conflict as he was appalled by the human carnage that resulted. His account of the battle itself is full of examples of courageous officers who led charges, rallied their men, and inspired others to emulate their bravery. One such incident concerned Lie

carrying his regimental flag, was surrounded with his battalion by a force ten times the size of his own. He was shot down, and as he rolled on the ground he clutched his precious charge to his heart. A sergeant who seized the flag to save it from the enemy had his head blown off by a cannon-ball; a captain who next grabbed the flag-staff was wounded too, and his blood stained the torn and broken banner. Each man who held it was wounded, one after another, officers and soldiers alike, but it was guarded to the last with a wall of dead and living bodies. In the end, the glorious, tattered flag remained in the hands of a Sergeant-Major of Colonel Abattuci’s regiment.7

Such passages could have come straight out of a regimental history, so completely do they reflect an uncritical acceptance of the glory of war. Not only men but even beasts were affected by the quest for glory: Dunant describes cavalry horses who were so “excited by the heat of battle” that they “played their part in the fray, attacking the horses of the enemy and biting them furiously, while their riders slashed and cut at one another.” Even a goat, which had evidently attached itself to a regiment of sharpshooters, “pushed fearlessly forward in the attack on Solferino, braving shot and shell with the troops.” Of his visit to French headquarters after the battle, he wrote, “The panoply of war which surrounded the General Headquarters of the Emperor of the French was a unique and splendid sight.” In short, Dunant’s romantic imagination was greatly stirred by this exposure to the battlefield.8

Nevertheless, it struck him forcefully that war produced enormous cruelty as well as great courage. The cruelty was most apparent in clashes between the Algerians, who fought on the French side, and the Croats, who fought with the Austrians. The Algerians, he wrote, “rushed at their enemies with African rage and Mussulman fanaticism, killing frantically and without quarter or mercy, like tigers that have tasted blood.”9 The Croats, he was told, were notorious for killing all wounded prisoners, such as the luckless Captain Pallavicini, whose skull they crushed with building stones. “We have real barbarians in our army,” one Austrian officer told him.10 Both the Algerians and the peasants of Lombardy (in whose fields the battle was fought) engaged in looting, particularly boots, which they took from the dead and dying.11 However, despite the behavior of the Algerians, Dunant praised the French army not only for “the courage of its officers and men” but also for “the humanity of simple troopers.”12

Dunant’s description of the misery produced by the battle faithfully reflected the social outlook of a nineteenth-century bourgeois. More than half of his book is devoted to the sufferings endured on both sides of the conflict by the wellborn, who are identified by name as well as by regiment and rank. Dunant was particularly moved by the fate of the young Prince of Isenberg, who was found alive after the battle only because the return to camp of his riderless horse touched off a special search; if the Prince “had been raised sooner by compassionate hands from the wet and blood-stained earth on which he lay senseless, [he] would not be suffering still today from wounds which became serious and dangerous during the hours when he lay there helpless.”13 If the men of the aristocracy endured danger and hardship, the women of this class were equal to the challenge: “The gracious and lovely ladies of the aristocracy, made lovelier still by the exaltation of passionate enthusiasm, were no longer scattering rose-leaves from the beflagged balconies of sumptuous palaces to fall on glittering shoulder straps, on silks and ribbons, and gold and enamel crosses; from their eyes now fell burning tears, born of painful emotion and of compassion, which quickly turned to Christian devotion, patient and self-sacrificing.”14

On a different level altogether was Dunant’s discussion of the sufferings of ordinary soldiers. Although he related several examples of the dreadful tortures undergone by the horribly wounded, including the most unforgettable description of a battlefield amputation ever written, it is clear that courage, honor, and valor were for him the prerogatives of the aristocracy.15 The common soldiers that he liked best were those who bore their fate with fortitude. He was particularly taken by the “resignation generally shown by these simple troopers…. Considered individually, what did any one of them represent in this great upheaval? Very little. They suffered without complaint. They died humbly and quietly.”16 He was especially moved by those who feared that their wounds might make it impossible for them to work again and that, as a consequence, they might become a burden to their families.17 As a devout evangelical Christian, Dunant was also upset by the fact that so many common soldiers died with curses and blasphemies on their lips, with no one beside them to bring words of consolation.18 Both virtue and industry among the lower classes threatened to become casualties of modern warfare.

If, in matters of class, Dunant expected the wellborn to display loftier emotions than the common people, in matters of nationality he found the “amiable … chivalrous and generous French” more admirable than the stolid and unremarkable Austrians. He quoted General von Salm’s comment to the Chevalier du Rozel on being taken prisoner at the battle of Neerwinden (1793): “What a nation you are! You fight like lions, and once you have beaten your enemies you treat them as though they were your best friends.”19 To be sure, in Italy local sentiment was strongly for the French, with the result that after the battle “the French met with kindness from everyone,” whereas “the Austrians had no such good fortune.”20 The Lombard peasants also found that the French were willing to pay very high prices for the supplies that they requisitioned.21 Differences in national character were particularly evident, according to Dunant, in the response to misfortune: “For the most part … [the wounded Austrian prisoners] lacked the expansiveness, the cheerful willingness, the expressive and friendly vivacity which are characteristic of the Latin race.”22 By contrast, “In the French soldiers could be noted the lively Gallic character, decisive, adaptable and good-natured, firm and energetic, yet impatient and...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half title

- Title page

- Copyright Page

- Table of Contents

- List of Illustrations

- Preface and Acknowledgments

- List of Acronyms

- Creditsfor Illustrations

- Introduction: The Sacred Cow and the Skeptical Historian

- Part One The Civilizing Mission

- Part Two The Militarization of Charity

- Part Three The Pains of Rebirth

- Note

- Selected Bibliography

- About the Book and Author

- Index