eBook - ePub

The Fractured Metropolis

Improving The New City, Restoring The Old City, Reshaping The Region

- 260 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

The Fractured Metropolis

Improving The New City, Restoring The Old City, Reshaping The Region

About this book

This book provides a thorough analysis of cities and the entire metropolitan region, considering how both are intrinsically linked and influence one other, targeted at architects, students, urban designers and planners, landscape architects, and city and regional officials.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access The Fractured Metropolis by Jonathan Barnett in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Architecture & Architecture General. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Topic

ArchitectureSubtopic

Architecture General1

Introduction: The Fractured Metropolis

American cities are splitting apart. Traditional downtowns still have their ring of old urban neighborhoods, but nearby suburban villages and rural counties have been transformed into a new kind of city, where residential subdivisions extend for miles and shopping malls and office parks are strung out in long corridors of commercial development.

The old city contains most of the deteriorated housing, the high-crime areas, and what is left of the original smokestack industries, plus the office, government, and cultural concentration downtown, and the fashionable districts of fifty or a hundred years ago, which may still be attractive places to live.

The new city has more than half the recently built office space, many of the best shops, the cleanest industries. Its residential areas are mostly middle or upper income; although lots may be small, houses and apartments are large, luxurious, and new; so are the schools.

The old city is fighting for its life: its tax base is in danger; its schools are in trouble; its streets are unsafe. Although the development boom of the 1980s has subsided, the new city is still prosperous and peaceful, except where its sprawling growth has enveloped older communities with problems of their own.

This division between old cities and new has been created in the last generation. It is different from the familiar separation of rich and poor neighborhoods, or of city and suburb. It affects the new metropolis in the Sun Belt or on the West Coast as much as older urban concentrations in the Northeast and Middle West.

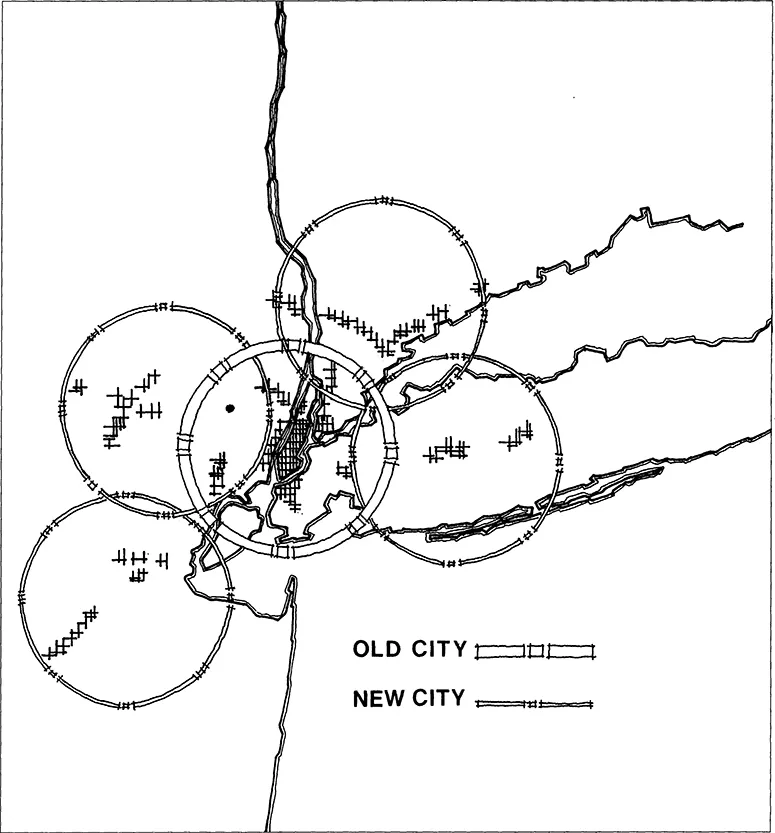

The new city in metropolitan St. Louis centers on Clayton, still a suburb but now also a major office location, and extends to include development along the U.S. 40 and Interstate 70 corridors. A circle encompassing these new urbanized areas takes in the desirable western neighborhoods of the city of St. Louis; but most of the circle includes recently built outlying residential districts that are more connected to new office parks, factories, and shopping malls than to the old city center [1]. A similar new city can be found north of Baltimore, centered on Towson; northwest of Chicago around Schaumberg; or east of Phoenix, around Tempe and Scottsdale. The same kind of diagram could be drawn for Miami/Coral Gables, Dallas/North Dallas, Seattle/Bellevue, Minneapolis/Bloomfield, Houston/Houston Galleria, San Diego/La Jolla, Atlanta/North Atlanta, Pittsburgh/Monroeville. Even a relatively small metropolitan area like Charleston, South Carolina, has split into Charleston/North Charleston, and many a small-town Main Street has been deserted for a new, outlying shopping mall.

Bigger urban regions can have more than one new city. The Philadelphia metropolitan area has one around Valley Forge and King of Prussia, northwest of the old downtown, and a second around Cherry Hill, northeast of Camden, New Jersey. It is possible to make a diagram that shows three new cities in metropolitan Washington, D.C., and four around New York [2].

The separation between old and new city began with the spread of post–World War II residential development, supported by federal mortgage insurance and the mobility conferred by car ownership. This migration to the suburbs made possible the first shopping malls and suburban corporate headquarters. Next, factories moved from constricted urban areas to expansive greenfield locations, a massive relocation process sustained by the new interstate highways, which made railside connections optional. The factories drew people from the old urban neighborhoods, generating demand for more new houses and shops. Then, as more women entered the workforce, the suburban labor market could support more and more offices.

New expressways built to serve old commuting patterns instead drew development outward; the beltways and ring roads designed to help long-distance travelers bypass cities became a new variety of main street. By the mid-1970s, shopping centers could be found around the whole periphery of the city, and the majority of office space was being built away from downtowns in office parks or highway commercial strips, conveniently near the homes of top executives or by the airport. Back in the old city, downtown stores began to close, factories were abandoned, and whole neighborhoods became derelict.

2. The old New York City metropolitan area is surrounded by four new cities. One includes suburban areas north and east of Manhattan, with major urbanization along the Cross Westchester Expressway, and in downtown White Plains, New York, and downtown Stamford, Connecticut, which used to be small suburban business districts. A second new city is located around Morristown, New Jersey, with the urbanized area extending northward to Whippany, Parsippany, and Troy Hills and south to formerly rural communities like Bernardsville and Basking Ridge. A third new city extends along the Route 1 corridor on both sides of Princeton, New Jersey, while Long Island has its own new city, with the main focus around Huntington. The Manhattan business center is peripheral to the area of influence of each of these new urban concentrations. The urbanized New Jersey shore might be considered a fifth new city.

The pace of change accelerated in the 1980s. Builders constructed master-planned communities of thousands of new houses, and other rural areas were transformed by the combined effect of many smaller developments. Much of this new housing was built at densities that used only to be found in close-in urban neighborhoods: large houses on small lots, attached townhouses, and garden apartments. In the meantime, malls and office parks converged into corridors and concentrations equivalent in importance to traditional city centers.

The older cities worked hard to fight the trends and keep the tax base necessary to support aging residential neighborhoods, the accumulated stock of subsidized housing, and ever-growing social programs. Cities devised sophisticated public-private partnerships and transformed the design of downtown: assembling land, building parking garages; manipulating the tax code for office buildings and hotels; constructing cultural centers, convention centers, and festival market places; promoting downtown housing; improving the streetscape. Cities also used subsidies to retain industry in urban locations, or to lure it back.

These efforts have often worked. The rapid expansion of urban areas in the 1980s was accompanied by a downtown development boom. But the shiny new skyline and elegant downtown mall draw attention away from devastated inner-city neighborhoods, and from schools and social services struggling to keep up with accelerating numbers of people in need. Even the cities like Portland, Oregon, Minneapolis, and Boston that have been the most successful in renewing themselves look to the future with uneasiness, as do big centers that once thought they were invulnerable, like New York, Chicago, and San Francisco. Other cities, such as Camden, New Jersey, or Gary, Indiana, have such severe problems that it seems impossible for them to solve them on their own. In the older parts of every city, factories continue to leave and offices and stores to close; in some neighborhoods abandonment and deterioration have been followed by situations where law and order seem to be breaking down completely.

Meanwhile the developing new city has its own problems. For years, the most rapidly growing suburban towns and counties continued to assume they were satellites of established city centers. They were not prepared to become centers themselves. Their zoning and subdivision ordinances had been written when a major change meant adding a few dozen houses, or building a new supermarket on Main Street. Planning boards struggled with development proposals for huge shopping centers, massive office parks, residential subdivisions of hundreds and even thousands of acres. There were no precedents for the scale of these new developments or the speed with which they were constructed. Because each component was proposed separately, by competing developers, the shape of the new city did not emerge until it was accomplished fact. It became far more fragmented, ugly, and inefficient than if it had been planned in advance by either government or a single entrepreneur.

The most obvious defects of the new city are traffic gridlock, the deteriorating natural environment, bad planning and shoddy construction. Many strip shopping centers and jerry-built town-house and garden-apartment clusters have a doubtful economic future. There are also more subtle problems of personal alienation and social disconnection.

Older cities and suburbs grew up around rail transportation systems, which concentrated development within walking distance of train stations and transit stops, or in corridors close to trolley routes. Out in the newly developing areas everyone at first assumed that automobile access on local roads and highways would be sufficient, and part of the attraction of moving a business to the new city was freedom from traffic congestion and the old commute downtown.

Today many newly urbanized areas experience almost continuous rush-hour conditions, with short breaks in the midmorning and midafternoon. Saturday, when everyone is out doing errands, can be the worst day of all. Fewer people commute along the highways from suburb to downtown and more commute from place to place within the new city, often on roads that were never planned for heavy traffic, and have been widened and improved ad hoc. Attempts to encourage minivan routes or car pools have relatively little success; and the new city is too spread out and fragmented to be served effectively by the minimal bus systems found in most areas.

Each shop or office building has to provide its own parking, so each structure is surrounded by asphalt, fragmenting development even more. Individual companies or investors seeking relief from traffic and from squalid corridors of continuous parking lots, garish signs, and disorganized, contending architecture seek new sites on the urban fringe. Others soon follow and the pattern repeats itself, accompanied by even more scattered development and traffic.

One of the reasons for escaping the old city was to enjoy the natural environment, an ambition often frustrated by rapid urbanization. Losing familiar scenery to standardized houses, massive buildings, and parking lots strikes many people as sufficient reason to change development policies, but the issues go beyond aesthetic preferences. Regrading hillsides, which requires removing natural vegetation, placing streams in culverts, or paving over large areas for parking were all acceptable techniques for managing development when they were exceptions within a largely natural environment. Once whole regions are regraded, paved, and channeled, there is a high risk of undesirable environmental change: flooding, soil erosion, greater temperature extremes, falling water tables, contaminated aquifers.

The expanding city also requires more and more natural resources to sustain it—not just land, but the fuel for all the extra automobile trips, water supplies for newly urbanized areas, and the construction materials to duplicate the buildings and infrastructure left behind in the old city. As natural systems become overloaded in the new city, air and water pollution, somewhat improved in the old city after years of expensive upgrading of factories and infrastructure, become serious problems over an increasingly large area.

There is also an uneasy feeling that life in the new city has an alienated quality. Out in two-acre-zoning country, old ideas of neighborhood and neighborliness are hard to sustain: borrowing a cup of sugar from the house next door might mean a five-minute walk. People living in new town-houses or garden apartments are close to their neighbors, but without street-life and local schools or services they have all the disadvantages of concentrated urban life without the amenities. The parent as chauffeur has become a familiar description; when most houses are built on large lots or in isolated clusters, schools and parks are inevitably out of walking distance for all but a few children, and school friends can live long distances apart. Domestic errands also take a lot of driving time when residential zoning districts can extend for miles, without permitting so much as a convenience store. Shops and services are zoned into narrow strips of land along a few main highways, meaning that customers must drive from store to store, generating more trips and more congestion. For some, spending a lot of time in a car alone may be a welcome respite from frantic offices and demanding home life. Car phones, radios, and tape decks are compensations for solitude; but hours of daily automobile travel have become a necessity for many people whether they like it or not.

Of course, life in the new city is attractive; offering spacious residential neighborhoods with beautifully tended lawns and gardens, gatehouse protection, offices in parklike settings, all kinds of convenient shopping—hence the new city’s continuing ability to draw the vitality out of older areas. Most people who have moved to the new city are aware that they have adopted a way of life created as an escape from community social responsibilities. At the back of consciousness, they know that the new city cannot be a permanent refuge if the old city does not survive and prosper. The split between the old city and the new is irreversible, but the current situation is just a phase in a still evolving pattern. The question is: What will happen next?

Corporate headquarters and research installations are beginning to move to rural sites beyond the new city. Land is easier to find, development approvals are faster, and the journey to work from the new city out to a rural area avoids most of the places where traffic gridlock takes place now. For example, Sears has moved its merchandise division from its tower in downtown Chicago to an office campus in Hoffman Estates, 37 miles from the Loop, and 12 miles farther out than the office concentration in Schaumberg. J. C. Penney has moved to Plano, beyond the northern fringe of the Dallas metropolitan area; Chrysler’s new technology center is in Auburn Hills, about 35 miles north of downtown Detroit. Hoffman Estates is way beyond the rapid-transit system and rail network that serves the older parts of metropolitan Chicago; Plano is a long way from south Dallas; Auburn Hills is a long way from Detroit. The corporate decision-makers who chose these locations had to know that very few people from old city neighborhoods would be able to make the commute. If employment centers continue to move out in this way, the new city will be effectively severed from the old.

Corporate offices have been leaving the old city for a long time. Banks, brokerage houses, insurance companies, and public utilities—plus the lawyers and accountants that serve them—have remained in downtown office centers because they need big clerical staffs and thus a central location in the largest possible labor market.

Long-predicted innovations in technology and communication have recently begun to transform these businesses. Back-office clerical activities are moving out of the downtown headquarters building. The first moves were to cheaper space in the same city, but once the back office is at the other end of a telephone wire, or fiber-optic cable, it doesn’t seem to matter where it is. Boston’s State Street Bank has its back-office operations in suburban Quincy; much of Citibank New York’s back office is now in Sioux Falls, South Dakota. Once the front office no longer needs to be next to a big back office, the old city downtown is no longer the only practical headquarters location for financial businesses and utilities.

When United States manufacturing industries lose business to foreign companies and are left with overcapacity in the United States, the logical plants to close are the oldest, in the most constricted urban locations. Most current plant closings are taking place in old factory towns and the older parts of metropolitan areas.

These are disturbing trends. If corporations are choosing rural locations beyond commuting distance for inner-city workers, and if employers no longer need their central-city clerical offices and factories, where does today’s old-city resident find tomorrow’s job?

People in areas without jobs are going to move if they can: populations are falling in many older cities, while the percentages of people on welfare are rising. As a city’s social problems increase and its tax base goes down, it enters a familiar downward spiral of deteriorating maintenance, services, and public safety. The big downtown corporations subscribe to redevelopment plans and send executives to conferences on the future of the city, but if old cities continue to deteriorate, it is only a matter of time before the remaining major businesses start looking seriously for alternatives.

Is the old city a write-off? Is it destined to be replaced by new suburban and exurban development? Only an extraordinarily rich country could even contemplate such a possibility, and it still seems improbable. The replacement cost of buildings, roads, and utility services in any city would be higher than its total assessed valuation plus its entire capital debt; the cost of reproducing the whole urban establishment is probably beyond our national means. Real estate goes through cycles: one investor’s disaster is eventually another’s opportunity. Business also goes through cycles; Sioux Falls loses jobs in meat packing and gains them in data processing and telemarketing.

But it will take a long time for the business cycle to start solving the problems of cities. The next few decades, all the future that most people can cope with, could easily be a time of dangerous social conflict. The vitality could continue to be drawn from many older cities, making them more and more the places with the most problems and the least resources. Newly developing areas could continue to suffer from a surfeit of growth, creating more and more gridlock, which will require expensive corrective measures, and more degradation of the natural environment, which probably can never be repaired. Experience with the consequences of rapid urbanization leads to more bruising zoning battles, pushing development even farther away from the older urban centers and intensifying the split between old city and new.

In addition to the ethical questions raised ...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Table of Contents

- 1. Introduction: The Fractured Metropolis

- Part I: Improving the New City

- Part II: Restoring the Old City

- Part III: Reshaping the Metropolitan Region

- Suggestions for Additional Reading

- Illustration Credits

- Index