eBook - ePub

Criminological Controversies

A Methodological Primer

- 224 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Criminological Controversies

A Methodological Primer

About this book

This book is about how to study crime. It addresses the controversies in crime as a means of developing answers and of contributing to the resolution of disputes and as a means of introducing and explaining basic methods of a social science of crime.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

1 The Class and Crime Controversy

John Hagan

At one time, there may have been consensus that adverse class conditions cause crime. If this was true once, it is true no more. Prominent criminologists now write of the “Myth of Social Class and Criminality” (Tittle et al., 1977) and ask, “What’s Class Got to Do With It?” (Jensen and Thompson, 1990). The question of whether class causes crime is more complicated than it may at first seem, and simple answers are elusive. Nonetheless, we begin this book by attempting to clarify and answer this question. We begin this chapter by considering historical and ideological aspects of the class and crime controversy.

Class and Crime in Time

Riesman (1964) describes sociology as a “conversation between the classes.” Although “conversations” linking class and crime predate both modern sociology and criminology, this metaphor usefully highlights the layers of meaning that often are communicated in discussions of class and crime. Popular discourse of earlier eras included frequent references to the “dangerous” and “criminal classes” and assumed that the poor and destitute were more criminal that those who were financially better off, while scholarly discourse today features discussions of an “underclass,” which is assumed to prominently include criminals. The notion of an underclass has evoked much controversy.

Discussions of criminal or dangerous classes are traced by Silver (1967) to eighteenth- and nineteenth-century Paris and London (see also Gillis, 1989; Tombs, 1980; Ignatieff, 1978), and they were common as well in nineteenth- and twentieth-century Canada and the United States (Boritch and Hagan, 1987; Monkkonen, 1981). For example, Daniel Defoe (1730:10–11) wrote of eighteenth-century London, “The streets of the City are now the Places of Danger,” while Charles Brace (1872:29) warned nearly a century and a half later in The Dangerous Classes of New York, “Let but law lift its hand from them for a season, or let the civilizing influences of American life fail to reach them, and, if the opportunity afforded, we should see an explosion from this class which might leave the city in ashes and blood.”

As Silver (1967:4) makes clear, these discussions of the dangerous or criminal classes referred primarily to the unattached and unemployed and to their assumed propensity for crime.

Although historians continue to write about conceptions of the dangerous and criminal classes of earlier periods and different places, today the dangerous and criminal class concepts probably are heard infrequently because they were used in such an invidious and pejorative fashion. Both popular and scholarly discussions of contemporary affairs refer to the “underclass.” Myrdal (1963) introduced discussion of the underclass to draw attention to persons driven to the margins of modern society by economic forces beyond their control. Marks (1991), however, has detailed a different direction in the contemporary development of the concept of the urban underclass, calling particular attention to the place of crime within that underclass. The current controversy surrounding the underclass conceptualization is partly that, like earlier discussions of the dangerous or criminal classes, it also can be used or interpreted in pejorative ways.

Marks (1991) noted that Auletta (1982:49) distinguished four distinct elements of the underclass: “hostile street and career criminals, skilled entrepreneurs of the underground economy, passive victims of government support and the severely traumatized,” while Lemann (1986, 41) characterized this class in terms of “poverty, crime, poor education, dependency, and teenage out-of-wedlock childbearing.” Often race is embedded in these characterizations, leading to debate about the extent to which the U.S. underclass is a black underclass. But what is most striking in these discussions is the extent to which the modern underclass, like its historical precedents described by Silver (1967), is defined by the association with crime of the unattached and unemployed. Marks (1991:454) asked, “Is … criminality the major ingredient of … underclass status?” Her concern was that “the underclass has been transformed from surplus and discarded labor into an exclusive group of black urban terrorists.”

Declassifying Crime

There are both scientific and ideological reasons to carefully consider the modern linkage drawn between class and crime in the concept of the underclass. Gans (1990:272) argued that this new concept is itself “dangerous” because by focusing on crime and other non-normative behaviors in discussing the underclass, “researchers tend to assume that the behavior patterns they report are caused by norm violations on the part of area residents and not by the conditions under which they are living, or the behavioral choices open to them as a result of these conditions.” Gans concluded that the effect is to identify and further stigmatize a group as “the undeserving poor.”

However, this criticism is unfounded in its association with William Julius Wilson’s (1987) discussion of the underclass in The Truly Disadvantaged. This book focused on concentrations of joblessness among the ghetto poor as explicit causes of crime and violence in these communities. Wilson (1991:12) is careful to make clear that his thesis is not confined to Black American ghettoes, noting that “the concept ‘underclass’ or ‘ghetto poor’ can be theoretically applied to all racial and ethnic groups, and to different societies if the conditions specified in the theory are met.” Wilson’s work has stimulated important new research on urban crime and poverty (e.g., Sampson, 1987; Matsueda and Heimer, 1987), and he (1991:6) worries that “any crusade to abandon the concept of underclass, however defined, could result in premature closure of ideas just as important new studies on the inner-city ghetto, including policy-oriented studies, are being generated.” Wilson (1991) interchanges the term “ghetto poor” for “underclass” in his recent writing, while other authors sometimes refer to low income or distressed communities.

Nonetheless, the scientific utility of some uses of the underclass concept is open to question, at least for the purposes of theorizing about crime. Insofar as the conceptualization of the underclass includes within it the cultural (e.g., attitudes and values) and structural (e.g., joblessness) factors assumed to cause crime, as well as crime itself, it may be little more than a diffuse tautology. A tautology is a description posing as an explanation. Tautologous formulations seem to tell us more than they do, as when the famous analyst of baseball, Yogi Berra, instructed us, “You can see a lot by just watching.” Seeing and watching are, of course, the same thing. Similarly, Billingsley (1989:23) noted, “If one asks how is underclass different from poverty, the answer is that it includes poverty. If it is asked how does it differ from unemployment, the answer is that it includes unemployment.… And now street crime has been added.”

It may partly be this feature of some discussions of the underclass, like the dangerous and criminal class conceptualizations before it, that has engendered skepticism in criminology and limited our understanding of connections between class and crime.

From Class and Crime to Status and Delinquency

Prominent theories of crime also emphasize the harsh class circumstances experienced by poor and even more desperate segments of the population (see Matza, 1966; Hirschi, 1972), and these theories causally connect these adverse class conditions with serious crime (e.g., Merton, 1938; Shaw and MacKay, 1942; Cohen, 1955; Miller, 1958; Cloward and Ohlin, 1960; Colvin and Pauly, 1983). However, these theories separately identify class conditions and criminal behavior as distinct phenomena and then propose an association between the two. The association between class and crime proposed in these theories is largely taken for granted in descriptive ethnographic research (Liebow, 1967; Howell, 1973; Anderson, 1978; Rose, 1987; Hagedorn, 1988; Monroe and Goldman, 1988; Sullivan, 1989), and it also is observed in most research that uses census tracts or other measures of neighborhoods (e.g., from Chilton, 1964 to Sampson and Groves, 1989) to link class and crime. We will say more about these ethnographic and community level studies later.

Meanwhile, the association between class and crime is only weakly, if at all, reflected in self-report analyses based on surveys of individual adolescent students attending school (e.g., Tittle et al., 1977; Weis, 1987), leading to calls for the abandonment of class analyses of crime. Self-report studies are undertaken in a survey or interview format and use what some have called a “confessional” methodology in asking adolescents to reveal their delinquent behaviors. These studies sometimes find weak patterns, and often no significant tendency at all, for children of lower status parents to be more delinquent. Since these self-report studies are at variance with many theories of crime as well as ethnographic and community level studies reviewed later, there might seem grounds to simply reject the former method and its results. However, doing so risks underestimating the valuable role that self-report studies have played in the advancement of criminological theory. Self-report methodology (e.g., from Nye and Short [1957] through Hindelang et al. [1981]) has allowed researchers to gather extensive information otherwise unavailable about individuals, which can then be used to explain their reports of criminal behavior. Self-reports also have freed researchers from reliance on potentially biased official records of criminality. This methodology has underwritten classic contributions to theory testing in criminology (e.g., Hirschi [1969]; Matsueda [1982]).

In many such efforts, self-report survey researchers provide separate measures of the concepts of class and crime. In doing so they implicitly have questioned the taken-for-granted nature of associations of crime and poverty in much criminological writing. Self-report survey researchers rightly insist on distinct, independent measures of class and crime that can provide the building blocks for testing explanations of crime. Literary or statistical descriptions of crime-prone areas, the modern sociological analogues to Dickens’s and Mayhew’s early depictions of the dangerous and criminal classes of London, are not enough for the purposes of theory testing.

Instead of providing literary or statistical descriptions, self-report researchers moved into the schools of America (and later other countries) to collect extensive information on family, educational, community, and other experiences of adolescents. Three substitutions that we describe later characterized this process: (1) schools replaced the streets as sites for data collection; (2) delinquency replaced crime as the behavior to be explained; and (3) parents’ occupational status replaced criminal actors’ more immediate class conditions as the presumed causes of delinquency.

In some ways, these substitutions enhanced the scientific standing of criminological research, but they also distanced self-report studies from the conditions and activities that stimulated attention to the criminal or underclass in the first place. For example, although sampling lists can more accurately be established from schools than from the streets, it is out-of-school street youth who are more likely than school youth to be involved in delinquency and crime. Further, although adolescent self-reports of delinquency might be free from some kinds of mistakes and biases involved in official record-keeping about adolescents and adults, the more common self-reported adolescent indiscretions are also less likely to be the serious forms of delinquency and crime of more concern to citizens. Finally, parental occupational status can be indexed using established scales independent of the adolescent behaviors that researchers are seeking to explain. However, these well-developed measures assume that parents have occupations, although many may not have jobs and/or may be unemployed. Furthermore, note that these are measures for parents, not for the youth whose behaviors are being explained. These substitutions may make self-report survey research more systematic, but they also produce the unintended result that less theoretically relevant characteristics (i.e., parental occupational status in place of parental or youth unemployment) are used to explain the less serious behaviors (i.e., common delinquency in place of serious crime) of less criminally involved persons (i.e., school youths rather than street youths and adults).

Reclassifying Crime

Serious attempts have been made to improve on these features of self-report studies. These efforts at improvement most significantly have involved the use of parental and youth unemployment measures, which better represent class positions and conditions, instead of, or in addition to, the occupational status of parents. Wright (1985, 137) explained why this reconceptualization is important when he wrote that “all things being equal, all units within a given class should be more like each other than like units in other classes with respect to whatever it is that class is meant to explain” [emphasis in original]. The key to defining a class in this way is to identify the relevant linking conceptual mechanisms. For example, in economics or sociology, if income is the theoretical object of explanation, then educational attainment, whether an indicator of certification or skill transmission, is an obvious linking mechanism that must be incorporated in the measurement of class.

In criminology, our theoretical objects in need of explanation—delinquency and crime—demand their own distinct conceptual consideration. So we need to more directly conceptualize and measure our own linking causal mechanisms. These mechanisms may involve situations of deprivation, desperation, destitution, degradation, disrepute, and related conditions. Tittle and Meier (1990:294) spoke to the importance of such factors when they suggest that “it would make more sense to measure deprivation directly than to measure socioeconomic status (SES), which is a step removed from the real variable at issue.”

In other words, when serious street crime is the focus of our attention, the relevant concern is with class more than status—especially as class operates through such linking mechanisms as deprivation, destitution, and disrepute. These linking mechanisms are more directly experienced when the actors themselves are, for example, hungry, unhoused, ill-educated, and unemployed, but the linking mechanisms may also operate indirectly through parental unemployment and housing problems such as those involving associated family disruption, neglect and abuse of children, and resulting difficulties at school. Youth and parental unemployment experiences are important sources of these kinds of direct and indirect class effects, and some survey researchers therefore have focused on these measures in self-report studies.

However, Brownfield (1986:429) reported that efforts of those who do school surveys to identify class circumstances in terms of parental joblessness still have considerable difficulty finding and studying the disreputable poor. Consider the few studies that are available. Hirschi (1969) studied delinquency in Richmond; he counted any spell of unemployment over three preceding years and found 16 percent of the family heads were unemployed. By oversampling multiple dwelling units and depressed neighborhoods, Hagan et al. (1985) produced a Toronto sample in which 9 percent of the family heads were unemployed. Johnson (1980:88) also focused on parental joblessness and selected three Seattle high schools “in order to obtain a sufficient number of underclass students” who constitute 8 percent of this sample.

The Research Triangle Institute (see Rachal et al., 1975) oversampled ethnic communities and produced a sample in which about 7 percent of the youth lived in a household with an unemployed head. The Arizona Community Tolerance Study (see Brownfield, 1986:428) overrepresented rural families, 3 percent of which had unemployed heads, including many “miners who were temporarily laid off.”

More recently and most successfully, a panel study concentrated on high crime areas of Rochester, New York (Farnworth et al., 1994), has produced a sample in which one-third of the principal wage-earning parents were unemployed.

These are the only self-report studies we can find that report parental joblessness as a measure of underclass position. All attempt to overrepresent jobless parents, and all, with the recent exception of the Rochester study, find relatively few underclass families. It is particularly noteworthy that the Rochester study finds consistent evidence of a relationship between parental unemployment and self-reported delinquency but little indication of such a relationship when measures of occupational status are used.

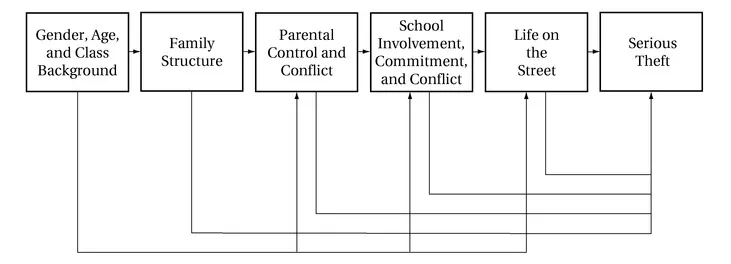

The limited study of, and variance in, parental unemployment reduces the likelihood of finding stable or substantial associations between parental class positions and adolescent delinquency. And there is the further and possibly more important factor that the influence of parental class on adolescent delinquency is from a distance. For example, the parental class effect is assumed to operate over as long as a three-year-lag in the case of the Richmond study. Furthermore, the effects of parental class is also presumed to be indirect, operating through the variety of family, school, and other mediating variables. For example, Figure 1.1 presents a causal model of delinquency from a study that includes both youth in school and youth living on the streets of Toronto (see Hagan and McCarthy, 1992). Note the succession of paths through which the effect of parental class background passes to cause delinquency. It is a rule of thumb in such models that the further removed a causal variable is from the ultimate outcome, the weaker its effect will be (Blalock, 1964). This rule of thumb suggests that the impact of parental class position on delinquency should be weak. And it is therefore not surprising that this indirect class effect is elusive and uncertain in self-report research.

Figure 1.1 A Conceptual Model of Streetlife and Serious Theft

Source: John Hagan and Bill McCarthy, 1992. “Streetlife and Delinquency: The Significance of a Missing Population.” British Journal of Sociology, vol. 43, pp. 533-61.

This shifts our attention to the more immediate and direct class effects of youth unemployment on crime and delinquency. Although there are many community level studies of crime and unemployment (Chiricos, 1987) that we consider later, there are again surprisingly few studies that focus on unemployment among individual adolescents. However, these individual level studies reveal higher levels of youth unemployment than is present in the studies focused on parents. Perhaps most importantly, these studies report the expected association between youth unemployment and youth involvement in delinquency and crime, even if the full nature of this association is only beginning to be understood.

For example, Farrington et al. (1986) reported that nearly half the sample of 411 London males followed in their research that tracked youths from ages 8 to 18 experienced some unemployment, and these youths self-reported more involvement in delinquency during the periods of their unemployment. This study (and further research reported later) allowed some consideration of the timing of crime and une...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Contents

- Dedication

- Prologue: The Fact of the Matter…

- 1 The Class and Crime Controversy

- 2 Testing Propositions About Gender and Crime

- 3 Urbanization, Sociohistorical Context, and Crime

- 4 Initial and Subsequent Effects of Policing on Crime

- 5 Subcultural Theories of Crime and Delinquency

- 6 The Drugs and Crime Connection and Offense Specialization

- Epilogue: Toward a Science of Crime

- References

- About the Book and Authors

- Index

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Criminological Controversies by John L Hagan,A. R. Gillis,David Brownfield,A R Gillis in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Social Sciences & Sociology. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.