Indigenous South Americans Of The Past And Present

An Ecological Perspective

- 504 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

About this book

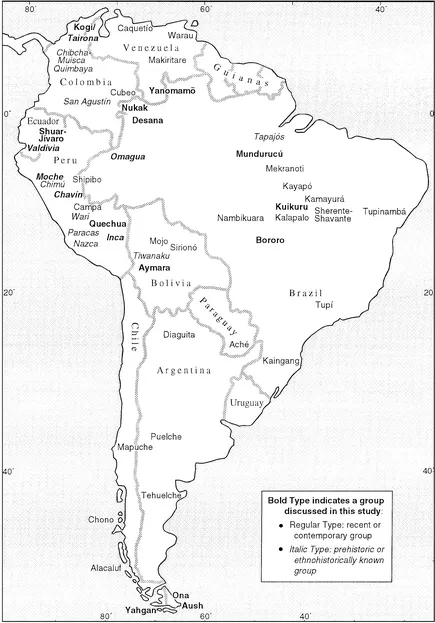

Utilizing ethnographic and archaeological data and an updated paradigm derived from the best features of cultural ecology and ecological anthropology, this extensively illustrated book addresses over fifteen South American adaptive systems representing a broad cross section of band, village, chiefdom, and state societies throughout the continent over the past 13,000 years.Indigenous South Americans of the Past and Present presents data on both prehistoric and recent indigenous groups across the entire continent within an explicit theoretical framework. Introductory chapters provide a brief overview of the variability that has characterized these groups over the long period of indigenous adaptation to the continent and examine the historical background of the ecological and cultural evolutionary paradigm. The book then presents a detailed overview of the principal environmental contexts within which indigenous adaptive systems have survived and evolved over thousands of years. It discusses the relationship between environmental types and subsistence productivity, on the one hand, and between these two variables and sociopolitical complexity, on the other. Subsequent chapters proceed in sequential order that is at once evolutionary (from the least to the most complex groups) and geographical (from the least to the most productive environments)?around the continent in counterclockwise fashion from the hunter-gatherers of Tierra del Fuego in the far south; to the villagers of the Amazonian lowlands; to the chiefdoms of the Amazon v¿ea and the far northern Andes; and, finally, to the chiefdoms and states of the Peruvian Andes. Along the way, detailed presentations and critiques are made of a number of theories based on the South American data that have worldwide implications for our understanding of prehistoric and recent adaptive systems.

Frequently asked questions

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Information

CHAPTER 1

Introduction

South American Indigenous Groups

- the Yahgan (Yámana) canoe people and the Ona (Selk'nam) guanaco hunters of Tierra del Fuego, located at the southern tip of the continent, both groups adapted to one of the most challenging environments anywhere in the world;

- the Chono and Alacaluf (Halakwulup) canoe people of the towering forests and deep fjords of the rainy Chilean archipelago;

- the Puelche and Tehuelche of the dry, grassy southern pampas of Argentina, who used multiple leather thongs with attached pouches containing stones (more succinctly called bolas) to bring down the ñandú, or South American ostrich, of this area; and

- the Sirionó, who until very recently roamed the humid jungles of eastern lowland Bolivia practicing a mix of horticulture and hunting-gathering that permitted the continuance of their essentially mobile lifestyle.

- the Bororo of central Brazil, whose complex on-the-ground village layouts represent one of the most interesting and complicated South American social organizations;

- the Sherente of central Brazil, who, like many other South American groups from the Amazon area to the Andes, live in opposing but complementary societal halves called moieties;

- the Tupinambá of the eastern Amazon Basin, now extinct, but infamous in early colonial times as cannibals who cooked their human victims in large pots;

- the Kayapó of the southern Amazon Basin, a fiercely independent and, to intruding Brazilian settlers at least, warlike people whose cause recently was taken up by anthropologist Darrell Posey and rock star Sting;

- the Mundurucú of the upper Tapajós River, in the southern part of the Amazon, known for their matrilocal marriage rule, the social solidarity of the women, and the long-distance raiding expeditions against unrelated groups carried out by the men, who, upon bringing human captives and trophy heads back to the settlements, returned in an exalted spiritual state that disallowed sexual relations for several years;

- the Yanomamö "fierce people" of northernmost Brazil and southeastern Venezuela, whose shamans, like many of those from Tierra del Fuego to the jungles of Venezuela, "throw" magical darts (called hekura, in Yanomamö) around their environment to cause any number of ills and, not surprisingly, the corresponding need for shamans in other villages to suck these darts out of the body in attempts to cure the intended victims; and

- the Shuar-Jívaro, of eastern Ecuador, who attacked nearby neighbors, including even their own kin, and until just recently shrank the heads of human victims killed on raiding expeditions to gain control over the soul power (called muisak) of the killed warriors.

- the Kogi of the Sierra de Santa Marta, northern Colombia, a still unassimilated people who recently invited outsiders from BBC television in for a brief stay in their mountain fastness to deliver, as our "elder brothers," a message aimed at averting further ecological disasters in what they see as the dying "civilized" world of we "younger brothers";

- the Colorados, who live in rain forests on the western slopes, of the Ecuadorian Andes and are so named because of the men's custom of dyeing their hair with a red paste made from the achiote plant;

- the Aymara and the Quechua, who live in the hundreds of thousands across the high grasslands, or puna, and adjacent deep valleys of the Andean countries of Bolivia, Peru, and Ecuador, and who, although partly assimilated into national economies, still maintain egalitarian village adaptations that date back several thousand years; and

- the Mapuche of central Chile, who were famous in the early colonial period for their fierce resistance to the European encroachment and who still maintain many aspects of their traditional way of life.

- the Tapajós of the lower Amazon River, who were made famous by the accounts of Francisco de Orellana both for their great numbers and sociopolitical complexity and for the fact that their war leaders appeared to be women (hence the name Amazons, from Greek mythology, given to the river);

- the Omagua of the upper Amazon River, whose settlements, like those of their downstream neighbors, appear to have extended for "leagues" along the main river channel and were based on the high productivity of the nutrient-rich waters of the main channel of the river;

- the Tairona, whose prehispanic chiefdom-level societies are ancestral to the village-level Kogi (which, as will be seen in a later chapter, raises the. issue of societal devolution in the face of the European intrusion);

- the Muisca, or Chibcha, of the central Colombian plateau around the modern city of Bogotá, famous, like other Colombian indigenous groups, for their exquisite gold-and-copper alloy artifacts made by the "lost wax" technique;

- the San Agustín culture, southern Colombia, well known for its production of large, free-standing stone statues; and

- the Valdivia and Jama-Coaque complexes: of coastal Ecuador, famous for their elegant modeled pottery figures and vessels as well as for the possible signs (of interest to diffusionist scholars) of influences from various far-flung places, including Polynesia and west-central Mexico.

- the Inca, whose imperial organization and highway system extended along the Andean mountain chain from what is now central Chile to the southern extreme of modern Colombia, a larger area by far than that occupied by any other polity in prehispanic South America;

- the Chimú of the Peruvian north coast, famous for their huge mud city of Chan Chán, one of the largest of such centers anywhere in the world;

- the Lupaqa and Pacaxes kingdoms of the Bolivian and Peruvian altiplano, or "high plain," around Lake Titicaca, famous among modern-day travelers to the area for their beautifully constructed stone burial towers, called chullpas here and elsewhere in the Andes;

- the Wari of the central Peruvian highlands, the probable creators of the first extensive state, or empire, in this part of South America and whose ancient capital lies near the modern city of Ayacucho;

- the Tiwanaku of the Lake Titicaca region, known both for their giant carved stone Statues with "weeping" eyes and for the highly productive ridged fields they constructed along the shore of the lake;

- the Nazca of the Peruvian south coast, known by almost anyone who has read about South America as the creators of an extensive (and still mysterious) series of lines and drawings etched out on nearby desert plains, or pampas; and

- the Moche of the Peruvian north coast, well known for one of the most elegant pottery styles ever produced in South America and, more recently, made famous around the world by the archaeological rescue from the hands of would-be tomb robbers of fabulous royal graves containing gold and silver artifacts and hundreds of other luxury goods.

Scope of This Book

Rationale: Ethnology and Archaeology

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title

- Copyright

- Contents

- List of Tables and Figures

- Preface

- Acknowledgments

- 1 Introduction

- 2 Theoretical Approach

- 3 An Overview of South American Environments

- 4 Subsistence and Sociocultural Development

- 5 Band Societies Present and Past

- 6 Amazonian Villages and Chiefdoms

- 7 Northwest Villages and Chiefdoms

- 8 Contemporary Central Andean Villages

- 9 Prehistoric Central Andean States

- 10 Toward a Scientific Paradigm in South Americanist Studies

- Glossary

- References

- Index