eBook - ePub

Requiem For The Sudan

War, Drought, And Disaster Relief On The Nile

- 385 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Requiem For The Sudan

War, Drought, And Disaster Relief On The Nile

About this book

After a decade of uneasy peace, the historic conflict between the North and South Sudanese erupted into violent conflict in 1983 This ferocious civil war, witti its Arab militias and widespread use of automatic weapons, has devastated the populace. In additon to the miseries of war, drought and famine took a further toll on an already battered societyalthough this regional calamity remains largely unknown to the outside world, over 1,000,000 people have either perished or been displaced. Furthermore, the Sudanese government seemed little inclined to help its own people Requiem for the Sudan provides a chilling account of the ravages of drought and civil war, graphically recounting how attempts by international agencies and humanitarian organizations to provide food and medical reliefhave been thwarted by bureaucratic infighting, corruption, greed, and ineptitude. Based on a wealth of previously unpublished documents, Requiem for the Sudan clearly illustrates how the failure of conflict resolution, organizational mismanagement, and a government hostile toward its own people had tragic human consequences.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Requiem For The Sudan by J. Millard Burr,Robert O Collins,J Millard Burr in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Politics & International Relations & Asian Politics. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

One

The Death of a Dream

The mutiny was local; it occurred in one battalion, and it was restricted to one province. The mutiny has ended completely, and it has not spread at all in the south.

—General Joseph Lagu, Khartoum, March 1983

At approximately 5:00 P.M. on 27 February 1972 in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia, Ezboni Mondiri Gwonza, representing the Southern Sudan Liberation Movement, and Dr. Mansour Khalid, minister of foreign affairs of the Sudan government, ratified the Addis Ababa Agreement and effectively ended civil war in the Republic of Sudan. The agreement halted a conflict that for over seventeen years had devastated the South and caused the deaths of an estimated half million southerners. The region's population had been scattered like chaff in the wind; some two hundred thousand Sudanese were found in neighboring countries and five hundred thousand of those displaced had burrowed into the hinterland, or bush, of Southern Sudan.1 The agreement was hailed by the international community as a triumphant example of how a nation could resolve a debilitating and divisive dispute through negotiation, compromise, and mutual respect. The president of the republic, Jaafar Numayri, an army colonel who had seized power in October 1969, basked in the glow of his role as peacemaker.

Aftermath of the Addis Ababa Agreement

The terms, but not the spirit, of the Addis Ababa Agreement were subsequently implemented. Refugees were repatriated, and the South's indigenous military movement, the Anya-Nya guerrilla fighters, were offered posts within the Sudanese army, police, or game warden system. By the end of 1976, 6,000 Anya-Nya officers and troops had been integrated into the army's Southern Command. Unfortunately, the expectations of a new era based on peace, equality, and social justice—not only

in the South but in all of Sudan—did not materialize. Large-scale development schemes made possible by peace and the infusion of Middle East capital were invariably located in Northern Sudan. Moreover, in the distribution of social services—schools, hospitals, communications—the South did not receive its proportionate share. Still, the South did achieve a large measure of regional autonomy complete with a southern legislative assembly and a High Executive Council.

Arabic remained the official language of Sudan, but English was declared the "principal language" for the southern region, "without prejudice to the use of any other [regional] languages."2 Soon, however, the southern politicians were squabbling among themselves, frequently maneuvering and manipulating for personal gain at the expense of public good. Gradually, the spirit of Addis Ababa expired. The hundreds of different ethnic cultures split along the great divide between the North—oriented to the Arab, Muslim world of the Middle East—and the South, whose peoples identified with the African, non-Muslim region stretching far to the south and west. It was this enormous difference in culture, religion, and mutual perceptions that the Addis Ababa Agreement had sought to resolve, and the great experiment failed when President Numayri ceased to believe in a political creation he himself had sponsored.

An attempted coup in 1975 and another in July 1976 swung Numayri and the Sudan's only party, his Sudan Socialist Union, irrevocably to the political right. Numayri turned to old foes in the Muslim Brotherhood, the Ikhwan al-Muslimin, for support and rebuilt bridges to the traditional sectarian political parties he had once prorogued. In 1977 he achieved a reconciliation with his principal opponents—the Umma, the Democratic Unionists (DUP), and the Islamic Charter Front (ICF, later renamed the National Islamic Front, or NIF), which were collectively known as the National Front. Although the National Front had sought to overthrow Numayri in the abortive but bloody 1976 coup d'état, the president was prepared to purchase their support at the expense of the South. He yielded to National Front demands to revise the Addis Ababa Agreement and eliminate what Arabs in the North regarded as the South's privileged status. Certainly, the Islamic Charter Front, the party representing the Muslim Brothers, cared nothing for Numayri or for southern aspirations; instead, it used the National Front to accumulate power for itself and its members.

From 1977 onward, the National Front abetted President Numayri's relentless ambition to undo the Addis Ababa Agreement, and in 1978 Front members were brought into the government and Numayri's Sudan Socialist Union. Subsequent events convinced the president that not only should he gut the Addis Ababa Agreement but that the surgery could best be accomplished through his espousal of Muslim ideology. Nevertheless, in 1980 Numayri suffered a reverse when united southern opposition forced him to abandon his scheme to redefine the border between North and South so as to arrogate the oil fields of the Upper Nile province. Numayri's fury increased when southern representatives in the National Assembly published a small pamphlet, The Solidarity Booklet, in which they criticized him personally and northern political figures in general. The last straw was the student riots that erupted during his visit to the South's prestigious Rumbek Secondary School in December 1982. From that point there was no turning back, and the split between North and South was irrevocable.

The Relocation of the Integrated Southern Forces

The Southern Sudanese armed struggle was precipitated by the mutiny of the 105th battalion of the Sudan army in March 1983. The battalion was composed of former Anya-Nya officers and enlisted personnel who had been "absorbed" into the army's Southern Command as part of the Addis Ababa Agreement. The absorbed forces, however, were not immune to the deteriorating relations between President Numayri arid the southern Sudanese elite. To be sure, most soldiers of the 105th were illiterate, and their horizons were limited; their world was their homeland south of the Sudd, the great swamps of the Nile north of which lay the hostile environment of Sahil, Muslims, and Arabs. They were only vaguely cognizant of the political machinations in Khartoum and of the various grievances expressed by the southern intelligentsia; their officers were aware, however, that no army recruitment had taken place in the South since 1974 and that southerners comprised less than 5 percent of those attending Sudan's prestigious military college. Moreover, they observed with great anxiety that retirement and dismissals had drastically reduced the number of southern Sudanese officers.

Although President Numayri had incarcerated twenty-four prominent southern leaders in December 1981 and the speaker of the regional assembly and the vice president of the High Executive Council of the South in February 1983, in his efforts to disestablish the Addis Ababa Agreement it was clearly more important to neutralize the Southern Command than to imprison a handful of fractious politicians. To immobilize the only possible armed resistance to his abrogation of the Addis Ababa Agreement, he ordered the relocation of most of the absorbed forces out of the South. In doing so Numayri demonstrated that he was suffering from acute political amnesia and had forgotten the lessons learned during nearly two decades of civil war in postcolonial Sudan. In August 1955 the Equatorial Corps of the Sudan Defense Force headquartered at Torit had been ordered to Khartoum to take part in the celebrations accompanying the departure of British troops from the Sudan. The Equatorial Corps, established in 1910, consisted solely of southerners under British officers; English was the language of command, and the religion, if any, was Christianity rather than Islam. As had occurred with the absorbed forces in 1983, the rank and file had intermarried with local families surrounding their posts. They established farms, reared families, and enjoyed the routine of garrison life. Thus a transfer to Northern Sudan was perceived as a removal from a friendly to a hostile environment. On 8 August No. 2 Company was on parade at Torit when it suddenly broke ranks and rushed the armory. Armed mutineers massacred Northern Sudanese officers, merchants, and their families, and rebellion swept Equatoria. Peace would not return until the ratification of the Addis Ababa Agreement in March 1972.

By 1983 President Numayri had dissipated the goodwill generated by the Addis Ababa Agreement. The pittance spent on economic development in the South, combined with Numayri's efforts to appropriate for the North the benefits of both oil discoveries in the South and the Jonglei canal construction in the Upper Nile, devalued and demeaned southern aspirations. Given the numerous personal and petty controversies among southern politicians, he considered the South an impotent giant. By far the most discordant political issues were the question of redivision, which could destroy the 1972 Addis Ababa Agreement, and the treatment of southern units in the Sudanese army. Eventually, the latter would be his undoing.

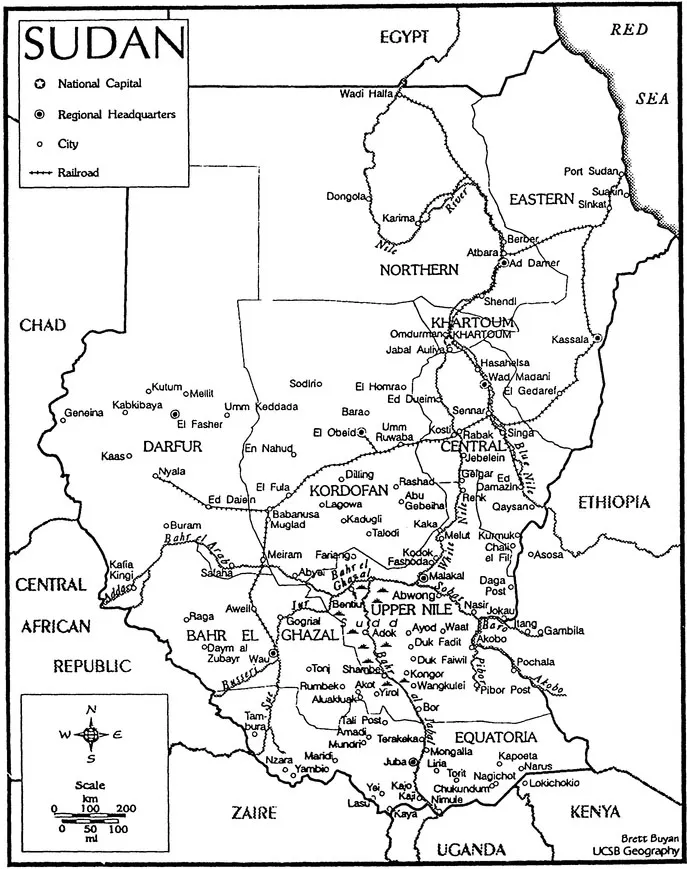

Most southern officers were absolutely opposed to the government plan to transfer the absorbed Anya Nya battalions to the North where they would be integrated into northern units. Nevertheless, Numayri was convinced that he had little to fear. He ordered the relocation of battalions 105 at Bor, 110 at Aweil, and 117 at Kapoeta in 1982 to 1983. Battalions 104 at Nasir, 111 at Rumbek, and 116 at Juba would move in 1983 to 1984. The Aweil unit received orders to relocate first but only after considerable persuasion departed for Darfur in December 1982. In contrast, the battalions at Bor and Rumbek refused to move, and only after the intervention of the High Executive Council at Juba did Numayri agree in January 1983 to postpone their transfer until later in the year. Although the concession temporarily mollified the 105th at Bor, the government, alleging mishandling of past payrolls, refused to reimburse the personnel. This transparent ploy, for there were no irregularities, only infuriated the Bor garrison. In retaliation the 105th and its units at Pibor, Ayod, and Pachalla mutinied. Units at Bentiu, the Upper Nile region, and Rumbek in the Bahr al-Ghazal region followed suit; and southern soldiers at the Raga garrison, a district headquarters located 225 miles northwest of Wau, refused orders to transfer to El Fasher, capital of Darfur, and "fled with their weapons."3

The Revolt at Bor

The National Defense Council in Khartoum concluded that discipline in the Southern Command had disintegrated. Thus an example would be made of the Bor garrison, and the Southern Command in Juba was ordered to disarm the 105th at Bor and Pibor. Government troops under the command of Dominic Kassiano, a Zande from Western Equatoria, were harassed on their march from Juba to Bor, and—eager for a fight— Kassiano's force attacked the 105th at dawn on 16 May. The attack was met with fierce resistance from soldiers commanded by a redoubtable southern soldier, Major Kerubino Kwanyin Bol. By sundown each side had sustained many casualties. At daybreak Kerubino, outnumbered and outgunned, led his troops into the bush and began the long march to the sanctuary of Ethiopia. In June the 105th's second in command, Major William Nyuon Bany, led a unit from Ayod to Ethiopia and joined rebel units from Bor and Pibor. There Kerubino and Nyuan Bany placed themselves under the overall command of Lt. Colonel John Garang de Mabior, who had been asked by President Numayri in March 1983 to try to resolve the most dangerous of the many festering disputes troubling the southern garrisons.

Garang had seemed the ideal choice, as he was from the Bor region and had served in the 105th. Still, as director of research at army headquarters in Khartoum, he had closely observed the corruption in the government and had watched with dismay Numayri's maneuvers to unravel the Addis Ababa Agreement. Born in Wangkulei north of Bor in Upper Nile Province on 23 June 1945, he had been sent to school at Rumbek by Protestant missionaries. Before he was able to graduate from secondary school, General Ibrahim Abboud, the Sudanese dictator from 1959 to 1963, initiated a campaign absolutely to destroy the thin stratum of educated Southern Sudanese. Garang was forced to flee to Ethiopia, and when an extradition treaty was signed between Abboud and Ethiopian Emperor Haile Salassie, Garang and other Sudanese made their way south. Garang eventually settled in Tanzania, where he obtained a scholarship to attend Magambia secondary school. He then left for Grinnell College in Iowa, where he earned a bachelor's degree in economics.

Upon returning to the Sudan in 1971 he joined the Anya-Nya— despite the reservations of its commander, Joseph Lagu, that he was overly educated. Following the signing of the Addis Ababa Agreement, he was commissioned a captain in the 104th battalion of the Sudan People's Defense Forces. Garang returned to the United States in 1977 and in 1981 earned a Ph.D. in agricultural economics at Iowa State University. After returning to Sudan, Garang was a popular lecturer at Khartoum University and the Sudan's military academy. Garang was deeply opposed to the monopoly of power exercised in Khartoum by Arab notables and their sectarian parties and to the diminution and political impoverishment of those Sudanese on the periphery—Muslim and non-Muslim, Arab and African.

When it became known that the Sudan army at Juba had been ordered to disarm and detain the mutineers, Garang was approached by the officers and troops of the Bor garrison and was asked to lead them in rebellion. Evidently, Garang did not take part in the fighting at Bor on 16 May, but the following morning he collected his family and following a long and tortuous route arrived in Ethiopia where he soon joined the troops of the 105th. From this nucleus Garang formed the Sudan People's Liberation Army (SPLA) and soon incorporated within its political arm the nascent Sudan People's Liberation Movement (SPLM).

In Khartoum it first appeared that the revolt at Bor was but another spontaneous mutiny that had been easily handled. Sworn in for his third successive term as president on 24 May, Numayri casually claimed that it "had been resolved sternly and forcefully."4 In fact, Garang was already galvanizing his forces in Ethiopia into a formidable revolutionary army, and by his own account more than 60 percent of those comprising the SPLA's first five battalions were battle hardened former Anya-Nya. Garang's first and most important political act was to publish a Manifesto on 31 July 1983. It spoke against the separation of the southern region from the Sudan and argued forcefully that the SPLA was fighting "to establish the united socialist Sudan, not a separate Sudan."5

As Garang sought to build a revolutionary army, he found himself challenged by the Anya-Nya II for leadership of that army. The Anya-Nya II was led by Samuel Gai Tut, a Nuer from Waat in the Upper Nile, and was made up of former Anya Nya who opposed the Addis Ababa Agreement. In 1975 Gai Tut, who had received training in Israel, had led a short-lived mutiny of the Akobo garrison after it received orders to prepare to move to the North. The southerners mutinied, shot their commander and seven men loyal to him, and, with their arms, headed for Ethiopia. Once reconstructed, the Anya Nya II forces reappeared in significant numbers in the Upper Nile region in the early 1980s. The dissidents made contact with Libya in 1981, and their movement began to receive arms in 1982. At first many villages opposed the rebels, but, according to one Westerner who knew the region well, by 1983 "this attitude had changed" and villagers "around Nasir spoke favorably of the guerrillas, contrasting their discipline with the lack of it among the Army."6 In early 1983 missionaries and international relief workers in Southern Sudan reported that they had "run into Anya Nya II road blocks where they saw military equipment as sophisticated as that used by the regular Sudanese army."7

Gai Tut was a confirmed secessionist who sought to entice Garang's followers to his standard, arguing that secession was the only way for the South to preserve its cultural integrity. The issue of unity versus secession was debated vigorously in the rebel camps until February 1984 when Gai Tut was killed during a confrontation with the SPLA. Thereafter, an Anya-Nya II faction joined the SPLA, and a remnant, under the command of William Abdullah Chuol, retired to Malakal where it was soon reconstituted as a militia and used by the army to fight the SPLA. Although Garang consolidated military control, few Southern Sudanese politicians rallied to the SPLA, and most questioned the movement's aims. Some opponents supported separation, whereas others abhorred the SPLA's frequent use of revolutionary Marxist jargon; the split also reflected the deep differences that existed between the Dinka—which dominated the SPLA leadership—and other Southern Sudanese ethnic groups. The South, which contained about 25-30 percent of the nation's population, was a melange of at least forty tribes. Unlike the first civil war, spearheaded by Anya-Nya soldiers born in and operating from Equatoria, the second civil war would be led by Dinka from the Upper Nile and Bahr al-Ghazal. The Dinka were regarded with suspicion by the peoples and politicians of Equatoria, for they comprised about 40 percent of the South's population and contained by far the largest number of highly educated individuals in the South.

Unlike Joseph Lagu, the unsophisticated leader of the Anya-Nya I, Garang was quick to adapt the precepts of modern guerrilla warfare to the Sudanese bush.8 He could not be bought with offers of political power as Numayri had bought Lagu. Moreover, Garang did not consider the movement a regional revolt; rather, it was a national rebellion opposing Numayri and the northern politicians unwilling to share power with the South. He soon won over many Nuer and Anuak in the Upper Nile and some Taposa of eastern Equatoria—all tribes long considered enemies of the Dinka.9 The SPLA also attracted some Nuba from South Kordofan and occasional Fur from Darfur. It eventually attracted some Muslims, the most important being Mansour Khalid...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title

- Copyright

- Contents

- List of Illustrations

- Preface

- List of Acronyms

- Introduction

- 1 The Death of a Dream

- 2 The Politics of Food

- 3 Battering the Dispossessed

- 4 Starvation in the South

- 5 The International Response

- 6 Operation Lifeline Sudan

- 7 The Return of the Military

- 8 The Junta Is Challenged

- 9 Escalating the War and Reducing Relief

- Conclusion: A Decade of Despair

- Notes

- Bibliography

- About the Book and Authors

- Index