![]()

1 The Vikings on the eve

A furore normannorum, libera nos, domine. (From the violence of the men from the north, deliver us, O Lord.)

This might well be taken as the epitaph chiselled by general historical opinion on the Viking gravestone. The phrase – there is no evidence that it ever became part of the monastic litanies – sums up the hostile treatment frequently given to the Vikings by historians of the early Middle Ages: the wild Vikings proved a temporary threat to the progress of western civilization. They belong, it is said, on the periphery of events, far removed from the central events of the ninth, tenth and early eleventh centuries. They were, like the Magyars and the Moors, irritants, negative and destructive, hostile to Francia, the historical centre of Europe at that time. The traditional story begins or, at least, rises to a high pinnacle with the coronation of Charlemagne at St Peter’s in Rome on Christmas Day in the year 800. We are told variously that this event was the central point of the early Middle Ages, that it was the first attempt by the Germanic peoples to organize Europe, that it was the event which provides a focus for European history till the eleventh century and beyond. Political theorists have taken this event, however they may interpret it, as a landmark in the struggle between ‘church and state’. And, we are told, the main lines of European history follow. Charlemagne established an empire or, at least, a large area of western Europe under Frankish control: from the Danish March to central Italy. This so-called empire collapsed under his son and his grandsons. With the treaty of Verdun in 843 there began the dismemberment of this empire, and within a hundred years the once united empire of Charlemagne had been fractured and left in hundreds of pieces, some tiny, others large, all virtually separate and autonomous units. Then, the traditional story continues, the East Franks in Saxony slowly began to rebuild and Otto I took the imperial title in 962. His successors developed a strong East Frankish state; in 1049 this development reached its climax when Henry III placed on the papal throne Leo IX, who started the work of papal reform. The promise of Charlemagne was now fulfilled. Thus, in this accounting, the story of European history from the beginning of the ninth century till the mid-eleventh century is the story of the rise and fall of the Carolingian empire and the rise of its German successors. Who can doubt this?

Doubt, however, should arise, for this traditional view has as its focus Francia; the rest of Europe, while not forgotten, is thrown out of focus and placed on the margin of events, peripheral to what was happening in the lands of Charlemagne and his successors. The nationalist historians of the nineteenth century, particularly the French and Germans, in search of their national origins have set the historiographical agenda for the twentieth century and, one fears, the twenty-first century: thus, this Charlemagne-Otto I-Henry III school of historical writing. The Viking invaders, to them, were merely a negative, destructive force which accelerated the decline of civilization in the west. Relying overmuch on the monastic chronicles, the nationalist historians seem to have forgotten the other destructive forces at play in the Europe of the time. What of the internecine wars among the Irish tribes or the Anglo-Saxon kingdoms or the Frankish peoples? The Vikings have become a convenient whipping boy.

This book argues that the traditional focus is misplaced: if there is to be a single focus, it should not be centred on the Carolingians and their successors but, rather, on the Scandinavian peoples of northern Europe and on the peninsulas of the north where the dynamic forces of Europe were to be found. The Viking civilization of the north, vibrant, untamed and raw, had a strong and unmistakable impact on much of the rest of Europe and on lands across seas and oceans. While Charlemagne was receiving the imperial crown in the year 800, the Vikings were harassing the coasts of England, Scotland and Ireland and setting up bases in the Orkneys and the Western Isles. Before the death of Charlemagne in 814, they had interdicted the northward progress of the Franks. To the court of his son, Louis the Pious, there came with an embassy from Constantinople in 838 Vikings who had undoubtedly reached Byzantium through Russia. While the grandsons of Charles were carving out their petty kingdoms, destined to be carved into smaller and smaller pieces, the countryside of Francia was almost constantly raided by these people from the north. Within a hundred years of the death of Charlemagne the Vikings had set up kingdoms in Ireland, in the north and east of England and in Russia as well as an overseas settlement in Iceland. These warrior-seamen of Scandinavia were to travel as far west as the shores of North America and as far east as the Volga basin and some even beyond.

An uncritical obsession with a European history with Francia and, later, the empire and the papacy at its centre has caused the historian to think of the Viking only in passing. This franco-centric view has, strangely enough, caused attention to be placed on the decline of a prematurely organized state with its tedious list of soubriqueted kings. The dynamic and vital forces in Europe are not to be found in a decaying civilization but rather in the exuberant, at times destructive warrior-seamen who sailed from the northern European peninsulas and whose legacy can be traced in lines through Normandy, Sicily, the Crusades and an Anglo-Norman state whose laws have come to form the basis of legal systems in North America and elsewhere. Let us look to the north.

Scandinavia

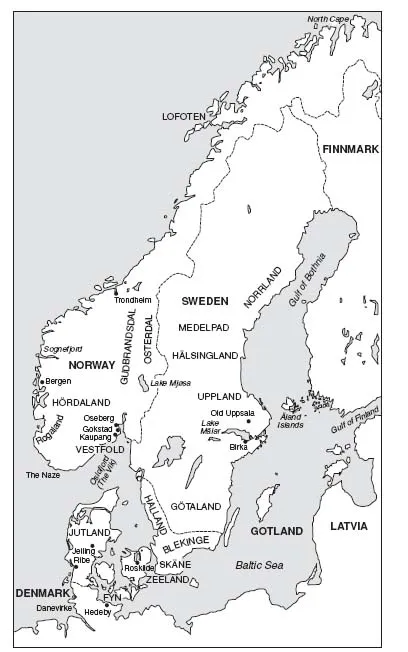

It was from the northern European peninsulas that the Vikings came: from the Jutland peninsula and its easterly islands and from the Norwegian-Swedish peninsula and the Baltic islands offshore. The three lands from which they came – which we would now call Norway, Sweden and Denmark – cover vast areas. If one leaves the northern tip of Scandinavia at Cape North and travels to Rome, one is only half-way when southern Denmark is reached. Yet, in a sense, this is misleading, for this land was not thickly settled in the Viking period: we are dealing with a very large area with a scattered population, and beyond the Nordic peoples were others such as the Lapps. These three places face the sea in different ways: the face of Denmark to the west and southwest; the face of Norway to the west and, so to speak, to the far west; and the face of Sweden to the east and southeast. If we are to look for a key to the geography of these places, it is in the mountains and fjords of Norway, the dense forestland of Sweden and the size of Denmark.

Norway, a vast land, then as now mostly uninhabitable, extends over 1,600 miles along its coast and 1,100 direct miles from its southern tip, The Naze, to Cape North, well above the Arctic Circle. The same northwestern European highlands which can be seen in Donegal and across Scotland stretch through almost the full length of this land, which looks like the upturned keel of a ship (thus, the name of these mountains, The Keel), and leave Norway with an average altitude of 500 metres above sea-level. Its western shore is punctuated by fjords; some of these long, deep-water inlets (for example, the Sognefjord) extend over a hundred miles into the interior. Fertile lands can be found in the southeast, in the lands near the waterways around the head of the Oslofjord and north from there on a line through Lake Mjøsa and the Osterdal and Gudbrandsdal valley systems to Trondheim. West of this fertile land is high plateau country reaching out towards the Atlantic and a coastline ragged, island-dotted and indented by deep fjords. Fertile lands can also be found in narrow rims between the mountains and the sea and along narrow, glaciated valleys. The favourable Atlantic climate usually keeps the western fjords ice-free throughout the year; today the mean January temperature at Lofoten, above the Arctic Circle, is −4°C (25°F). Although access to Sweden was possible through tortuous mountain passes, the normal internal and external means of communication was over the seas. By sea, Bergen lies nearer to Scotland than to Sweden. Settlements were scattered along these fjords and, perhaps, there were also nucleated settlements in the southeast. From fjord settlement to fjord settlement it was the highway of the sea that joined people together. Any national (i.e., Norwegian) feeling would be a long time in becoming crystallized, and the political organization of these people would have to wait for Harald Finehair (c.890). Even then, the extent of effective political control under him might have been limited only to parts of this large and sparsely settled land.

Map 2 Viking Age Scandinavia.

Much less mountainous than Norway, its neighbour Sweden had, at the beginning of the Viking period, a few large settlements. The one at Uppland, inhabited by the Swedes (Latin, Suiones), was centred on Old Uppsala. Its land formed the northern edge of the central European plain and, although at one time thickly forested, by the eighth century Uppland was sufficiently cleared to maintain its people. South of Uppland, separated by dense forests, Gotaland lies in an area which contains perhaps the most fertile land on the peninsula. To the north of Uppland, again separated by forest and bog land, large areas of which were impenetrable, were the very thinly settled regions of Halsingland and Medelpad, and beyond, in another world, the arctic regions of Norrland and Finnmark. The Baltic island of Gotland (to be distinguished from the mainland Götaland), possibly the ancestral homeland of the Goths, who descended upon the Roman world in the late fourth century, was ideally situated along trade routes to the littoral of the Baltic and beyond to the heartland of what was to become Russia. Separated peoples all; their primary identification was local and particular, rather than national. Although Uppland was clearly the most powerful part of Sweden by the eighth century, the extent of the hegemony of its kings over the peoples of Gotland and Götaland is not clear.

Much more homogeneous geographically and politically was Denmark, consisting of the other northern peninsula, Jutland, and the islands, particularly Fyn and Zeeland, to the east. It should be remembered, also, that the extreme south of modern Sweden (Skäne, Halland and Blekinge) belonged in this Danish orbit during the Viking period and for a long time thereafter. The neck of the peninsula, largely barren in our period, provided a barrier between the Danes and their southern neighbours the Saxons and the Slavs. Most of Denmark was fairly flat and lent itself, where cleared, to the growing of grain and the raising of livestock. Its maritime nature made fishing in the neighbouring waters a fruitful industry. In about the year 800 Denmark had a strong king in Godefred and was perhaps the most politically advanced of these northern European countries.

The Scandinavians inhabiting these lands lived mostly in scattered settlements and farmsteads, yet at least four major trading centres existed: Kaupang in Norway, Hedeby and Ribe in Denmark and Birka in Sweden.

Situated on the western shore of the Oslofjord (The Vik), Kaupang was the smallest of the four. It was visited in the late ninth century by Ohthere, a Norwegian from Helgeland. He said that the place was called Sciringesheal and that it was a market. Its modern name, Kaupang, means a market. Recent archaeological evidence has clearly identified this site. The water-level has dropped 2 metres since Viking times, and aerial photography and a keen archaeological imagination are necessary to see in the modern remains a market-place situated on a bay and sheltered at its back by hills and at its front by islands and shoals, many of them then submerged but now visible. Excavations in the market and in the hinterland, particularly rich in graves of the Viking period, reveal objects from the British Isles, the Rhineland and the eastern Baltic. The commodities traded at Kaupang probably included iron, soapstone and possibly fish. Yet, Kaupang ought to be viewed more as a stopping-off point for traders on their way from Norway to the Danish town of Hedeby than as a terminal market.

Ohthere, a traveller from Norway, when he called at Kaupang, was, in fact, on his way, to Hedeby, five days’ further journey. The largest of the towns of Scandinavia, Hedeby had a life almost coterminous with the Viking period. It probably came into existence during the eighth century when three small communities combined at a point in the neck of the Jutland peninsula where a stream enters a cove of the Sleifjord. Extensive excavations since the late nineteenth century have revealed a town facing east towards the fjord, its back and sides protected by a semi-circular rampart, two-thirds of a mile long, which was built in the tenth century and rose to a height of nearly 10 metres. The 60 acres within the rampart contained dwelling places of both the stave-built (horizontal as well as vertical) and the wattle-and-daub varieties. It had a mixed population of Danes, Saxons and probably Frisians, but from about 800 the Danes were predominant. In about 950 an Arab merchant, al-Tartushi, from the caliphate of distant Cordova, visited Hedeby and recorded his vivid impressions of the place.

Slesvig [i.e., Hedeby] is a large town at the other end of the world sea. Freshwater wells are to be found within the town. The people there, apart from a few Christians who have a church, worship Sirius. A festival of eating and drinking is held to honour their god. When a man kills a sacrificial animal, whether it be an ox, ram, goat or pig, he hangs it on a pole outside his house so that passers-by will know that he has made sacrifice in honour of the god. The town is not rich in goods and wealth. The staple food for the inhabitants is fish, since it is so plentiful. It often happens that a newborn infant is tossed into the sea to save raising it. Also, whenever they wish, women may exercise their right to divorce their husbands. An eye makeup used by both men and women causes their beauty never to fade but to increase … Nothing can compare with the dreadful singing of these people, worse even than the barking of dogs.

How barbaric it all must have seemed to this man from the magnificent splendour of Islamic Spain. Did he know, one wonders, that it was the Danes, some perhaps from Hedeby itself, who, a century or so earlier, had sailed up the Guadalquivir and attacked Seville in the heartland of this mighty caliphate? Even at the time al-Tartushi was writing Hedeby’s days were numbered. In the middle of the eleventh century it died: burned by Harald Hardrada in 1050, ravaged by Slavs in 1066 and, in the end, probably abandoned as the water-level receded.

Ribe in west Jutland had a flourishing fur trade probably from the eighth century. The early site lies opposite the town and its cathedral on the north bank of Ribe River, and excavations have discovered numerous ninth-century coins and evidence of workshops and commerce. Firm dates are hard to come by, but sometime in the early eighth century, possibly about the year 700, there was a market-place there, which seems to have been in use only seasonally at first. The evidence suggests that the market was reorganized in 721/2 and lasted until the middle of the ninth century.

Birka in central Sweden may have been the wealthiest of the northern trading centres. Although there is evidence of commercial connections between Birka and Dorestad in modern Holland and with the Rhineland, its main trade was with the east, particularly with Muslim traders whom Swedish merchants would meet among the Bulgars at the Volga Bend. Coins found from the Islamic east in excavated graves on the site at Birka are seven times more numerous than coins found from the west. Situated on an island in Lake Mälar on the way to the open sea from Uppsala and nearly fifty miles west of modern Stockholm, Birka had its rampart to its back and sides. The Black Earth, so called because human habitation has coloured the earth, was the settled area; over it a commanding hill stood watch. Over 2,000 graves in the cemetery have provided archaeologists with the richest Viking site so far known. Extensive excavations undertaken between 1990 and 1995 have revealed 4,000 stratigraphic layers and 90,000 finds and find groups; indications are that Birka existed about the year 750 and was a centre for fur trading. Although the level of the lake has dropped at least six metres since Viking times, its demise as a thriving trading centre should rather be attributed to the breaking of trade links with the Arab world by Svyatoslav’s assault on the Bulgars at the Volga Bend (c.965).

How many other trading places like these four lie undiscovered or unstudied we do not know, but it would be rash to limit the early towns to these few.

Important as it is to stress the separate settlements of the north, the isolation of thinly settled areas from one another and the sense of localness of the peoples, it would be a mistake to think of the Scandinavians as having nothing in common save their northern lands. They were united by links stronger than those of politics and frequent human commerce: they shared a common language, a common art and a common religion.

Runic inscriptions of the eighth to the tenth centuries, which have been found in widely distant places in each of these lands, show a sameness of language. Spoken language, no doubt, differed from the written language and dialects of spoken language were inevitable, but these were the normal differences found in any language which is living and is used to communicate human needs and feelings. The primitive Nordic language (dönsk tunga, vox danica) was still in use among these Nordic peoples at the beginnings of the Viking Age. The Vikings in Vinland and the Vikings at the Volga Bend would have been intelligible to one another. Only later did the dönsk tunga give rise to the distinct languages characteristic of Norway, Sweden, Denmark and Iceland.

Likewise, a common art was shared by the Vikings in the north. Art historians refine our knowledge of Viking art and distinguish six different styles: Style III (Oseberg), Borre, its near contemporary Jelling, Mammen, Ringerike and Urnes. The surviving examples of these styles undoubtedly represent only a small fraction of the artistic output of the Viking period. As distinct as these styles no doubt were, in our context we should stress the similarities of these styles rather than their differences. No doubt dependent on earlier Germanic art and influenced by and, in turn, influencing Irish, Anglo-Saxon and Carolingian art, the distinctive art of the Vikings was an applied art found principally on wood and stone and, to a lesser extent, on metal. The semi-naturalistic ornamentation of functional objects made use of motifs with animal heads and their ribbon-like...