![]()

Part One

Introduction

IN THIS SECTION WE PRESENT AN OVERVIEW OF THE DIVERSITY OF RURAL communities and the community capitals that contribute to their degree of environmental health, social inclusion, and economic security. How is rural defined? What is the variation in ruralness across the United States? Watch the first episode, Who Cares? From the “Rural Communities: Legacy and Change” video instructional series (www.learner.org/resources/series7.html) to get an introduction to the book and the some of the places discussed in the text. It addresses why rural America is important to us as a nation, what steps should be taken to respond to rural communities in crisis, and what the future holds for these rural areas. In it, rural people show how the provision of water, recreation, minerals, and biodiversity come from rural areas and how the production of those shared resources contribute to values and cultures that support people and places. The differences among rural areas in the United States are shown, as are the different assets and issues that stem from those differences. Rural communities are sources of innovation in working together to resolve issues as they also increase their dependence on the rest of the world. Those who are rural by choice versus rural by heritage sometimes conflict, but they can come together through their commitment to place.

It will help in doing the assignments to choose a community with which you are familiar to analyze and to apply the concepts learned. If it is an urban community or neighborhood, it can help you understand what is unique about rural communities and what characteristics all communities of place share.

It is increasingly difficult to analyze rural-urban differences, as less and less data are available on smaller places (known as small-area data). Except for seven basic questions still asked on the census, the American Community Survey (ACS) has replaced the decennial Census of Population and Housing. The 2000 Census was the last that included the full battery of social, economic, and housing characteristics. The ACS has the advantage that it is conducted annually rather than once every ten years. As a survey rather than a complete census, it may in fact be more accurate than the census for larger jurisdictions. However, for smaller places and populations it is necessary to combine data for three or five consecutive years for the data to be reliable. A National Research Council panel (Panel 2015) analyzed options for increasing the accuracy of small-area data gathered in the ACS, but as is pointed out by Chevat and Lowenthal (2015), there is need for funds to test out new approaches for more efficient and accurate data collection, but such efforts are complicated by a failure of Congress to appropriate adequate funds, except in the couple years leading up to the decennial census. As government shutdowns, budget sequestrations, and cuts in research budgets and research personnel increase, separate rural data analysis is easy to drop, as there are few constituencies organized to demand it. An important source of available rural data—and all in one place—is the Atlas of Rural and Small Town America (Economic Research Service 2011).

Rural areas are increasingly linked to urban ones through migration, information technology, and social media, with less obvious differences in important norms, values, and symbols. Viewing rural, suburban, and urban as a continuum with a high degree of interaction does not deny the importance of considering rural communities, but it does suggest that the lessons learned about how community capitals work in rural communities can give us great insights into other settings as well.

![]()

1

COMMUNITY CAPITALS AND THE RURAL LANDSCAPE

THE RURAL LANDSCAPE

Christine Walden grew up in paradise. The daughter of schoolteachers in Mammoth Lakes, California, Christine spent her childhood surrounded by the majestic peaks, lush forests, and crystal-clear lakes of the Sierra Nevada range, nurtured by the closeness possible in a town of two thousand. In 1954 an all-weather road and a double chairlift opened, beckoning skiers to the north face of Mammoth Mountain. By 2013 the town’s population was over three times what it was in 1970, the year Christine’s parents first came to the community. Golf courses replaced horse pastures, as befits a major tourism destination. Multimillion dollar vacation homes adorn hillsides that once were covered with trees and native shrubs. Christine and her husband now work as teachers in the same school district for which her parents worked. But Christine no longer lives in Mammoth Lakes. Land development and speculation have driven housing costs beyond what the salaries paid by the local school district can support. The median house or condo costs over half a million dollars, and the average rent is over $1,200 a month. So the family lives in Bishop and commutes forty miles each way to work. Paradise has grown too expensive!

Wade Skidmore grew up working in coal mines. Part of the fifth generation of Skidmores to live in McDowell County, West Virginia, Wade in his childhood was shaped by what was underground rather than what could be enjoyed on the slopes of the rugged Appalachian Mountains. He attended school in Welch, the county seat, only through the tenth grade. Working in the mines didn’t require much education and offered him a chance to work at his own pace. For a time the work was steady and the pay was good. But as the price per ton of coal dropped, Wade found that he had to work harder to make ends meet. Then coal-loading machines came along—machines that could do the work of fifty men. Then some veins started giving out. Wade’s children are now growing up in poverty: substandard housing, water pollution from mine runoff, raw sewage in the streams, poor schools, and high illiteracy rates. McDowell County, which lost approximately 20 percent of its population between 2000 and 2013, has unemployment that is nearly twice as high as in West Virginia as a whole. Wade Skidmore lives in a region and among people trapped in persistent poverty. To make things worse, the town is susceptible to floods, as extreme weather events have increased in the last twenty years. A recent flood seriously damaged the Skidmore home located on the bank of the Tug Fork River—the only flat land around.

Ray and Mildred Larson face a decision. They farm near Irwin, Iowa, on land that they and Mildred’s three siblings inherited, and they split earnings from the farm four ways. They are worried that they will not be able to pay off the new planter and combine (combination harvester) they contracted to buy when corn prices were high. When hog prices were low in the late 1990s, Mildred’s parents got out of hog raising, growing only corn and soybeans. The Larsons get their seed, fertilizers, and herbicides from the Farm Services Cooperative in nearby Harlan, Iowa, and bought their new equipment from Robinson Implement, Inc. in Irwin. With the increase in corn prices beginning in 2007, they shifted their land from their previous rotations that included small grains into corn. Land prices increased very rapidly, making it difficult to acquire more land. So they plowed up marginal land they had put into the Conservation Reserve Program in order to plant more corn.

Irwin is a farming community that was settled as the railroads pushed westward across the Great Plains during the nineteenth century. The descendants of the early settlers still own some of the homesteads, such as the Larson place. The population of Shelby County declined 10.5 percent between 2000 and 2012, although nonfarm employment increased and unemployment is low. Ray and Mildred both hold full-time jobs off the farm. They wonder whether they should rent out their land or sell their equipment and find a farm management company so someone else will farm it.

Ray and Mildred know that in either case, the new operators would probably not buy machinery and inputs locally. They are also considering renting land from retired farmers to achieve the economies of scale needed to pay for their new machinery, even though corn and soybean prices are low, and cut back their paid employment during planting and harvest season so they can cover all the land.

Billie Jo Williams and her husband, Maurice Davis, are moving to Atlanta. Raised in Eatonton, Georgia, sixty-five miles from Atlanta, they grew up enjoying the gentle hills and dense stands of loblolly pine in Putnam County. Eatonton is home; both the Williams and Davis families go back to plantation days. But Billie can’t find a job. She just finished a degree in business administration at Fort Valley State College, and Putnam County is growing rapidly, its population increasing more than 14 percent between 2000 and 2013. But Eatonton’s population is decreasing, and other than in the apparel factory (which has now closed and moved overseas) or as domestic workers for the rich families who built retirement homes on the lake, there were few jobs for African American women in Eatonton when Billie Jo graduated high school. Unemployment rates are higher than for the state as a whole, and 31.4 percent of the population lives in poverty. Manufacturing, the major employers, are moving to other countries where people will work cheaper. Maurice settled into a factory job right out of high school but figures he can get something in Atlanta. The situation seems strange. In the twentieth century Eatonton did better than most communities in adapting to change, shifting from cotton to dairying to manufacturing and now to recreation/retirement economies. But in the twenty-first century most African Americans have a hard time finding jobs that pay a living wage.

________

Which is the real rural America—ski slopes of California, mines of West Virginia, farms in Iowa, or exurban resort and manufacturing communities in Georgia? Family farms and small farming communities dominate popular images of rural areas, in part because politicians, lobbyists, and the media cultivate those icons, supporting the myth that agricultural policy is rural policy. In fact, rural areas embrace ski slopes, mines, manufacturing, farms, retirement communities, Native American reservations, bedroom communities, and much, much more. In the twenty-first century, rural communities differ more from each other than they do, on average, from urban areas.

The diversity found among rural communities extends to the problems felt as each responds to the environmental, social, and economic change under way. Some rural and remote communities share the concerns of Irwin, wondering at what point their population will become too small to support a community. A few farming communities have grown as they take on the role of regional retail and service centers for surrounding small towns. The amenity-based community of Mammoth Lakes, California, faces rapid growth. Its citizens are grappling with how to protect both the environment and the small-town character they value. In Eatonton, Georgia, a long commute from several large urban centers, economic growth has been substantial with the expansion of the resort economy and nursing homes, but its majority black citizens have not shared equally in its success. Eatonton’s population is highly transient, and its poverty rate remains higher than that of the state of Georgia as a whole. Those living in mining-dependent McDowell County face poverty and high out-migration, despite the richness of the land surrounding them. Nearly one-third of the population falls below the poverty level, and median income is nearly $16,000 less than in the rest of West Virginia.

Despite the stereotype that life in the country is simpler, rural residents face many of the same issues and concerns urban residents do, plus those related to dispersion and distance. Indeed, rural and urban areas are linked. The garbage produced in New York City may find its way into landfills in West Virginia. Plastic products in Chicago are made from Iowa corn, grown with fertilizers that increase productivity but may endanger rural water supplies. A housing boom in San Francisco creates jobs in the lumber industry in Oregon. However, the jobs last only as long as the forests. Air-quality concerns in Boston could shut down coal mines in Pennsylvania.

This book examines the diversity of rural America—its communities, the social issues they face in the twenty-first century, and the histories that explain those issues. It also addresses ways that rural communities have built on their history and their increasing connectedness to creatively address those issues.

DEFINING RURAL

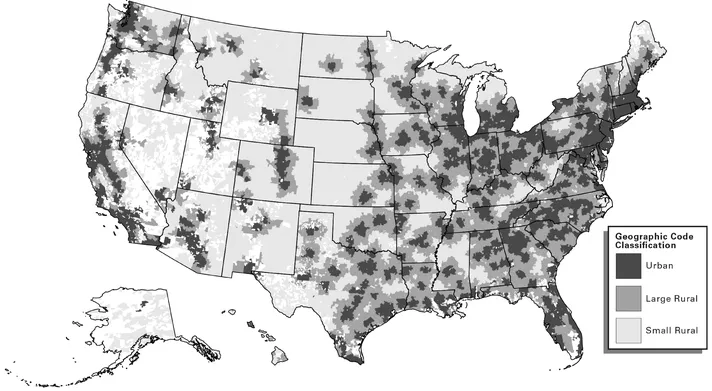

Giving a place a particular characteristic, thus “naming” it, suggests how people and institutions act toward it. When governments establish labels for places, they are generally for administrative purposes, to determine which places are eligible for specific government programs. When scholars establish labels, it is generally for analytical purposes, but because governments collect data, scholars often fall back on government labels. Media and advertisers use place labels such as “rural” to evoke particular images. In a consumer society rural is often defined by what one shops for in a place. Box 1.1 shows various governmental definitions of rural. In the past, small size and isolation combined to produce relatively homogeneous rural cultures, economies based on natural resources, and a strong sense of local identity. But globalization, connectivity, and lifestyle changes with shifting income distributions have changed the character of rural communities; they are neither as isolated nor as homogeneous as they once were. Figure 1.1 shows dispersion of population across the United States.

FIGURE 1.1 Urban and rural distribution. Source: Adapted from US Department of Health and Human Services, Health Resources and Services Administration, Maternal and Child Health Bureau. The National Survey of Children's Health 2007. Rockville, Maryland; US Department of Health and Human Services, 2011. Data from WWAMI Rural Health Research Center, 2006 ZIP Version 2.0 Codes, http://mchb.hrsa.gov/nsch/07rural/introduction.html.

Isolation

Part of the rural image is isolation, a sense that rural people live out their entire lives in the towns in which they were born. This was never true for all rural people. Loggers, miners, farmers, and a host of others routinely moved to wherever they could find work or land. However, some rural people were isolated. In parts of McDowell County, mountain men and women lived in “hollows” in the hills, living on game and part-time work in cutting wood or construction and creating a rich culture of self-sufficiency. Canals, railroads, highways, and airways have altered much of that isolation. Improved road systems have also changed rural residents’ occupations and spending patterns. Those living near urban areas often commute to work, living in one town and working in another. They buy many of their products in suburban malls. In regions where no metropolitan center exists, small towns, such as Harlan in Shelby County, have grown to become regional trade centers for towns like Irwin as people travel to the next-largest city to purchase products and obtain services.

Communication technologies have had an even greater impact on reducing isolation. Blogs and Twitter link rural residents with people who share their interests around the world. Rural residents now watch opera from New York, football games from San Francisco, the ballet from Houston, and congressional deliberations from Washington, DC, through satellite dishes. Rural people have become as literate, informed, and enriched as their urban counterparts. There is still a rural-urban connectivity divide, however: many residents on reservations in the Great Plains do not have phone service, much less broadband Internet connectivity, and wireless strategies based on satellites ...