- 192 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Internal Objects Revisited

About this book

The authors show how their ego-psychological object relations theory integrates drive theory and object relations theory and does justice to recent findings regarding the vicissitudes of transference and countertransference interactions in the psychoanalytic situation. 'A significant shift has taken place in the last few decades in the way in which psychoanalytic theory has developed and in its application to psychoanalytic technique. This development has, in essence, consisted in the ascendance of object relations theory as an overall integrating frame of reference linking psychoanalytic metapsychology closer to the vicissitudes of the psychoanalytic process. This has facilitated the formulation of unconscious intrapsychic conflict in more clinically helpful ways than has the traditional frame of reference exclusively based on the conflict between drives and defensive operations. 'The great interest of the Sandler's approach resides in their careful and systematic elaboration of what might be called the various "building blocks" of a contemporary ego psychological object relations theory, carefully exploring each areas on its own merits before gradually taking them into an overall theoretical approach.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

CHAPTER ONE

On the psychoanalytic theory of motivation

Introduction

The topic of motivation is an extraordinarily difficult one to study and has preoccupied psychologists for many years. A major problem has been the fact that neither in the field of general psychology nor in the more specific area of psychoanalysis is there agreement on what a motive really is. Even when we turn to the relatively restricted area of psychoanalytic theory, we find that we cannot be sure whether the term “motive” refers to drives, drive derivatives, affects, feelings, needs, wishes, aims, intentions, reasons, or causes. This chapter approaches the issue of object relationships from the side of the psychoanalytic theory of motivation and is essentially an account of the development of some ideas that led to the views presented in this book.

* * *

Some time ago—in 1959, when working with Anna Freud at what is now The Anna Freud Centre—I had the opportunity to present a paper to the British Psycho-Analytical Society. The first part was a theoretical consideration of feelings of safety, and the second was a short account of some analytic work with a woman I had commenced treating some nine years previously, who had been my first control case. The theoretical part of my paper, later published as “The Background of Safety”,1 presented the view that

the act of perception [can be regarded as] a very positive one, and not at all the passive reflection in the ego of stimulation arising from the sense-organs; … the act of perception is an act of ego-mastery through which the ego copes with excitation, that is with unorganized sense data, and is thus protected from being traumatically overwhelmed; … the successful act of perception is an act of integration which is accompanied by a definite feeling of safety—a feeling so much a part of us that we take it for granted as a background to our everyday experience; … this feeling of safety is more than a simple absence of discomfort or anxiety, but a very definite feeling quality within the ego; … we can further regard much of ordinary everyday behaviour as being a means of maintaining a minimum level of safety feeling; and … much normal behaviour as well as many clinical phenomena (such as certain types of psychotic behaviour and the addictions) can be more fully understood in terms of the ego’s attempts to preserve this level of safety.

The feeling of safety or security was, I argued, something positive, a sort of ego-tone, and as a feeling it could become attached to the mental representations of all sorts of different ego activities. Because of this, it was possible to postulate the existence of safety signals, just as we have signals of anxiety. I suggested that the safety signals were related to such things as the awareness of being protected by the reassuring presence of the mother, and that we could see in this the operation of what could be called a safety principle.

This would simply reflect the fact that the ego makes every effort to maintain a minimum level of safety feeling … through the development and control of integrative processes within the ego, foremost among these being perception. In this sense, perception can be said to be in the service of the safety principle. Familiar and constant things in the child’s environment may therefore carry a special affective value for the child in that they are more easily perceived—colloquially we say that they are known, recognisable, or familiar to the child. The constant presence of familiar things makes it easier for the child to maintain its minimum level of safety feeling.

The second part of the paper described the case of a woman of 35 who had been referred for sexual difficulties—more specifically, for the symptom of vaginismus.2 She was able to have what was regarded as a good analysis, as her sexual problems readily transferred themselves to the whole area of communication in the analysis. She had an obstinate though intermittent tendency to silence, and I commented that

It soon became clear that this paralleled, on a psychological level, the physical symptom of vaginismus. The similarity between the two was striking, and it seemed as if she suffered an involuntary spasm of a mental sphincter. In time we could understand something of her inability to tolerate penetration of a mental or physical kind, and as the silence disappeared in the course of analysis, so there was an easing of her physical symptom. It became clear that she wished me to attack her, to make her speak and to force my interpretations upon her. She was able to recall how her sexual phantasies in childhood had been rape phantasies, and the thought of being raped … had been a very exciting one.

I noted at the time that a central feature of her personality was her intense masochism and a highly sexualized need for punishment. The analysis resulted in the disappearance of the vaginismus and a general lessening of the patient’s need to inflict damage on herself.

Four years after we had stopped, I heard from my patient again. She was very anxious, as her husband, from whom she had separated, had been threatening suicide if she did not rejoin him. She started treatment again, and I saw her for a year. She did not have her vaginismus, but it transpired that she had another symptom—she was now mildly but noticeably deaf (having been diagnosed as suffering from nerve deafness). At the time I noted that it seemed “that this new symptom derived from the same unconscious processes that had led to her vaginal spasm”. In spite of working through all the previous material again, her deafness persisted. However, an understanding of this came rather unexpectedly. I suddenly became aware that my need to talk loudly so that she could hear me also caused me to shout pedantically, as if to a naughty child. This realization led me to the understanding that

… by being deaf she could force me to shout at her as her grandmother had done when she was very small. It became clear that she was unconsciously recreating, in her relationship with me, an earlier relationship to the grandmother, who had been, in spite of her unkindness to and constant irritation with the patient, the most permanent and stable figure in [her] childhood. With the working through of feelings of loss of her grandmother, and her need to recreate her presence in many different ways, [her] hearing improved.

I took the position in this paper that my patient was not only obtaining masochistic gratification through her symptoms, but was defending against an intense fear of abandonment by recreating a feeling of the physical presence of the grandmother, “whose mode of contact with the child had been predominantly one of verbal criticism or of physical punishment”. (We could now postulate that the transference reflected the externalization of an internal object relationship—or, as is discussed in later chapters, the actualization of a wishful transference phantasy reflecting an internal self-object relationship.) I added that “the pain and suffering was the price she paid for a bodily feeling of safety, for the reassurance that she would not undergo the miserable loneliness and separation that characterized her first year of life.”

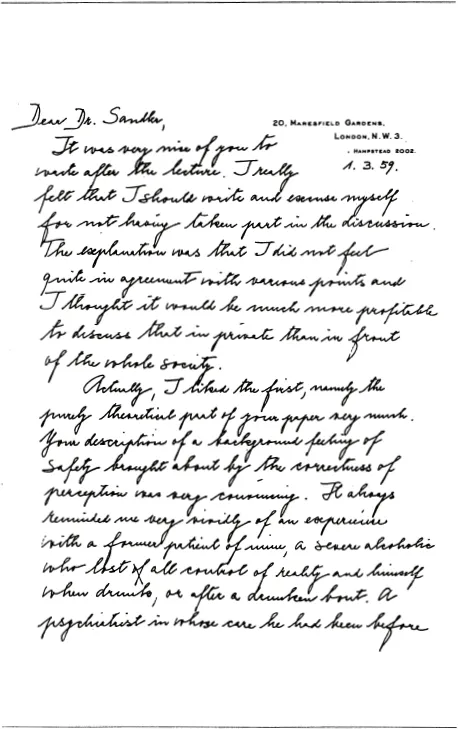

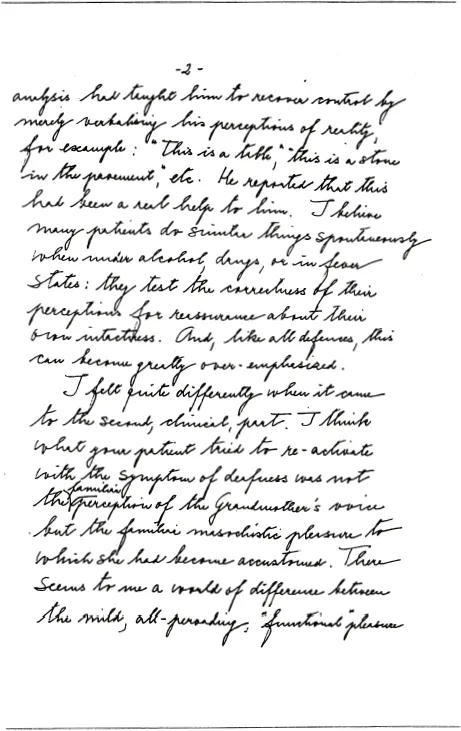

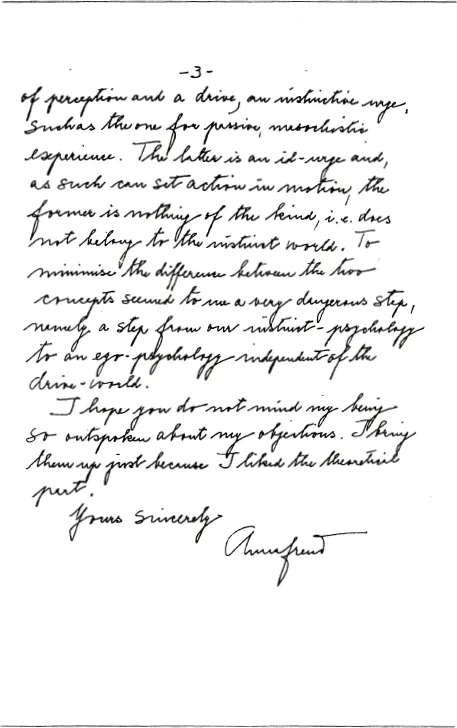

The week after I presented this paper, I received a letter, dated 1 March 1959, from Anna Freud. It was in reply to a short note of mine. She wrote—I must say, very sweetly—as follows

Dear Dr. Sandler,It was very nice of you to write after the lecture. I really felt that I should write and excuse myself for not having taken part in the discussion. The explanation was that I did not feel quite in agreement with various points and I thought it would be much more profitable to discuss that in private [rather] than in front of the whole Society.Actually, I liked the first, namely the purely theoretical part of your paper very much. Your description of a background feeling of safety brought about by the correctness of perception was very convincing. It always reminded me very vividly of an experience with a former patient of mine, a severe alcoholic who lost all control of reality and himself when drunk, or after a drunken bout. A psychiatrist in whose care he had been before analysis had taught him to recover control by merely verbalizing his perceptions of reality, for example: “this is a table”, “this is a stone in the pavement”, etc. He reported that this had been a real help to him. I believe many patients do similar things spontaneously when under alcohol, drugs, or in fever states: they test the correctness of their perceptions for reassurance about their own intactness. And, like all defences, this can become greatly over-emphasized.I felt quite differently when it came to the second, clinical, part. I think what your patient tried to re-activate with the symptom of deafness was not the familiar perception of the grandmother’s voice but the familiar masochistic pleasure to which she had become accustomed. There seems to me a world of difference between the mild, all-pervading “functional” pleasure of perception and a drive, an instinctual urge, such as the one for passive, masochistic experience. The latter is an id-urge and, as such, can set action in motion; the former is nothing of the kind, that is, does not belong to the instinct world. To minimize the difference between the two concepts seemed to me a very dangerous step, namely a step from our instinct-psychology to an ego psychology independent of the drive-world.I hope you do not mind me being so outspoken about my objections. I bring them up just because I liked the theoretical part.Yours sincerely,Anna Freud

Anna Freud was, of course, quite correct in her view that the pleasures associated with direct instinctual gratification have a quality that is markedly different from what she called “mild all-pervading ‘functional’ pleasure”. Without doubt, her major concern was, as she put it, to prevent what she saw as the dangerous step “from our instinctual psychology to an ego psychology independent of the drive world”. I think that we can understand this very well in view of the need of psychoanalysis, throughout its history, to protect its basic notions from those who wished to minimize the importance of infantile sexual and aggressive drives, and the role of persisting instinctual impulses of this sort in adult life.

I must confess that although I felt abashed by Anna Freud’s comments, a niggling feeling remained that neither of us had really come to grips with the problems involved in the disagreement between us, and it is only many years later that I found myself able to be more precise about where these problems lie. In what follows I shall attempt to work my way towards a suitable response to Anna Freud’s comments and shall do this by a less than direct route.

In the following year, under the influence of writers such as Edith Jacobson, Edward Bibring, and Annie Reich, I found myself referring, in a paper “On the Concept of Superego”,3 not only to feelings of safety, but also to feelings of well-being and self-esteem. It was possible to comment, for example, on the topic of identification as follows:

If we recall the joy with which the very young child imitates, consciously or unconsciously, a parent or an older sibling, we can see that identification represents an important technique by which the child feels loved and obtains an inner state of well-being. We might say that [through identification] the esteem in which the omnipotent and admired object is held is duplicated in the self and increases self-esteem. The child feels at one with the object and close to it, and temporarily regains the “good” feelings that he experienced during the earliest days of life. Identificatory behaviour is further reinforced by the love, approval, and praise of the real object, and it is quite striking to observe the extent to which the education of the child progresses through the reward, not only of feeling omnipotent like the idealized parent, but also through the very positive signs of love and approval granted by parents and educators to the child. The sources of “feeling loved”, and of self-esteem, are the real figures in the child’s environment; and in these first years identificatory behaviour is directed by the child toward enhancing, via these real figures, his feeling of inner well-being.

I went on to suggest that the same feelings can be obtained through compliance with the precepts of the superego introject or by identification with that introject, and I wrote that, in contrast to unpleasant feelings such as guilt and unworthiness, an

opposite and equally important affective state is also experienced by the ego, a state which occurs when the ego and superego are functioning together in a smooth and harmonious fashion; that is, when the feeling of being loved is restored by the approval of the superego. Perhaps this is best described as a state of mental comfort and well-being…. It is the counterpart of the affect experienced by the child when his parents show signs of approval and pleasure at his performance, when the earliest state of being at one with his mother is temporarily regained. It is related to the affective background of self-confidence and self-assurance…. There has been a strong tendency in psychoanalytic writing to overlook the very positive side of the child’s relationship to his superego; a relation based on the fact that it can also be a splendid source of love and well-being. It functions to approve as well as to disapprove.

On looking back at that paper, it now seems clear to me that I was struggling to deal with a conflict over my deep conviction that psychoanalytic theory had to take account of other strong motives that were not instinctual drive impulses—in particular, the need to experience or control feeling states of one sort or another. I was, I think, beginning to be involved in much the same sort of problem that concerned many others. At that time my way of dealing with the issue was to do what was perhaps commonly done—that is, to follow Freud in making use of his own solution to this theoretical conflict by shifting the emphasis from the drive impulse itself to the hypothetical energies regarded as derived from the drives and making the assumption that such energies entered into all motives. So I wrote, for example, that in identification with another person “some of the libidinal cathexis of the object is transferred to the self”; but in a footnote to the paper I commented:

The problem of what it means to “feel loved”, or to “restore narcissistic cathexis”, is one that has as yet been insufficiently explored. What the child is attempting to restore is an affective state of well-being which we can correlate, in terms of energy, with the level of narcissistic cathexis of the self.

Having said this, I was able to put drive energies to one side and to talk again about feeling states:

Initially this affective state, which normally forms a background to everyday experience, must be the state of bodily well-being which the infant experiences when his instinctual needs have been satisfied (as distinct from the pleasure in their satisfaction). This affective state later becomes localized in the self, and we see aspects of it in feelings of self-esteem as well as in normal background feelings of safety…. The maintenance of this central affective state is perhaps the most powerful motive for ego development, and we must regard the young child (and later the adult) a...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Dedication

- Table of Contents

- Preface

- Foreword

- 1 On the psychoanalytic theory of motivation

- 2 The striving for “identity of perception”

- 3 On role-responsiveness

- 4 On object relations and affects

- 5 Character traits and object relations

- 6 Stranger anxiety and internal objects

- 7 Comments on the psychodynamics of interaction

- 8 A theory of internal object relations

- Notes

- Bibliography

- Index

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Internal Objects Revisited by Anne-Marie Sandler,Joseph Sandler in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Psychology & History & Theory in Psychology. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.