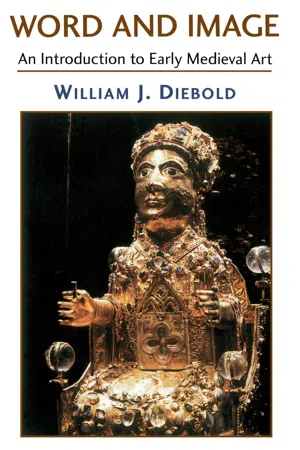

eBook - ePub

Word And Image

The Art Of The Early Middle Ages, 600-1050

- 176 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

This book provides an introduction to early medieval art, both the images themselves and the methods used to study them, focusing on the relationship of word and image, a relationship that was central in northern Europe and the Mediterranean from about 600 to about 1050.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Word And Image by William Diebold,William J. Diebold in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Art & Art General. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Topic

ArtSubtopic

Art General1

Books for the Illiterate?

Art in an Oral Culture

Christian legend holds that the religion had already reached northern Europe by the first century. Historical study indicates that the second or third century is a more likely date. And by the year 600, when the narrative of this book begins, Christianity was firmly established in some areas of Europe (Italy, southern France) but virtually unknown elsewhere (England, much of Germany). One of Gregory the Great’s goals was to spread Christianity to those who were not Christian and to regulate Christian practice among those who were. Gregory is crucial to our story because images are one of the means he used to achieve these goals.

In 597 the pope sent a mission to England to convert the pagan Anglo-Saxons. This mission, led by Augustine (not to be confused with the more famous fourth-century bishop, author of The Confessions and The City of God), encountered the Anglo-Saxon ruler Ethelbert on the island of Thanet just off the southeast coast of England. The meeting of missionary and pagan king was described in an eighth-century British source, Bede’s History of the English Church and People:

After some days, the king came to the island and, sitting down in the open air, summoned Augustine and his companions to an audience. But he took precautions that they should not approach him in a house; for he held an ancient superstition that, if they were practisers of magical arts, they might have opportunity to deceive and master him. But the monks were endowed with power from God, not from the devil, and approached the king carrying a silver cross as their standard and the likeness of our Lord and Saviour painted on a board.1

Two years after he sent the mission to England, Gregory wrote to Serenus, the bishop of Marseilles, on the Mediterranean coast of France. This region had long since been converted to Christianity, so Gregory’s problem here was not outside the church but inside it. Serenus was an iconoclast, a breaker of images. The pope, Serenus’s superior, reprimanded him for this practice:

I note that some time ago it reached us that you, seeing certain people adoring images, broke the images and threw them from the churches. And certainly we praise you for your zeal lest something manufactured be adored, but we judge that you should not have destroyed those images. For a picture is displayed in churches on this account, in order that those who do not know letters may at least read by seeing on the walls what they are unable to read in books.2

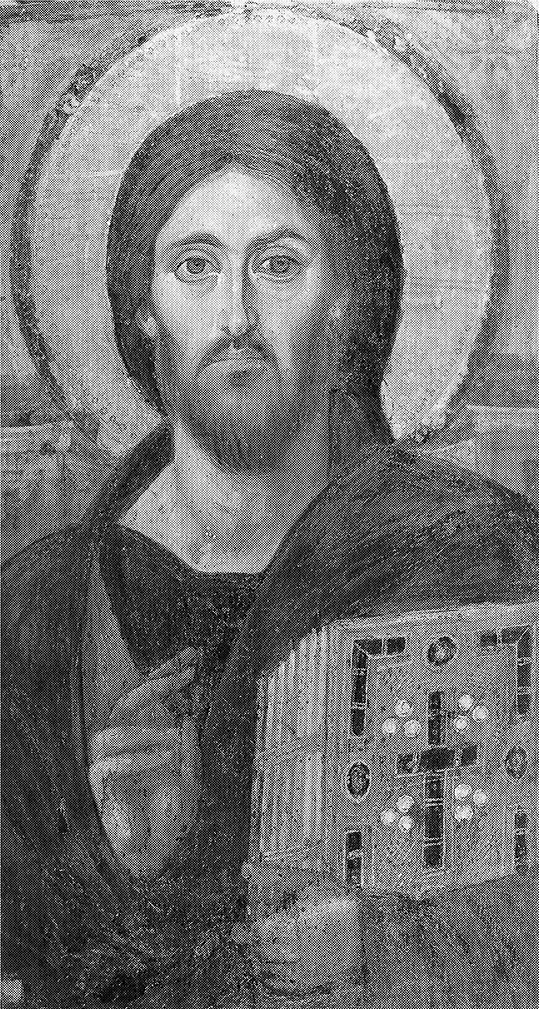

Both of these texts indicate the important role Gregory assigned to pictures. Augustine’s mission arrived with a likeness of Christ painted on a board (that is, an icon something like [i]). At Marseilles, Gregory condemned Serenus’s destruction of images, even though in Serenus’s estimation those images were being adored, a practice that Gregory agreed was unacceptable for Christians. By the end of the sixth century, then, images had become central to Christianity. Because Gregory’s pro-image position became the standard Catholic one, we miss its strangeness. With our knowledge of the importance of art in the later Christian church (for example, Chartres Cathedral in the thirteenth century or the Sistine Chapel in the sixteenth, to cite only two very different cases), Gregory’s endorsement of images seems natural. But in the early Middle Ages it was far from obvious that Christians would have images. Since virtually all of the art talked about in this book was made in the service of the church, it is important to understand how images achieved a central role in Christianity.

1 Icon of Christ. Constantinople (?), sixth-seventh century. Mt. Sinai, Monastery of St. Catherine. Reproduced through the courtesy of the Michigan-Princeton-Alexandria Expedition to Mt. Sinai

The question of the legitimacy of images arose for Christians because the two most important sources of Christian culture, classical antiquity and the Old Testament, both had their doubts about them. Plato’s condemnation of images as nothing more than deceptive imitations of the truth was influential in the early church. And in the Old Testament, God himself had questioned the value of art, commanding, “Thou shalt not make to thyself a graven thing, nor the likeness of any thing that is in heaven above, or in the earth beneath, nor of those things that are in the waters under the earth. Thou shalt not adore them nor serve them” (Exod. 20:4–5).3 Since the central Christian text, the New Testament, contains almost no reference to images, the Second Commandment was the most important statement on images for Christians. According to one strict reading, the commandment forbids representational art; thus, many Jews and Muslims prohibit images in synagogues and mosques. But from early on Christians tended to read the commandment more loosely, understanding the second part, “Thou shalt not adore them nor serve them,” as governing the entire commandment. It was all right to make representational images as long as they were not worshiped. Art was fine, but idolatry was prohibited.

As Serenus’s actions indicate, this looser interpretation of the Second Commandment did not please everyone. Unfortunately, we know almost nothing about what the practices were around images in Marseilles that drew Serenus’s wrath. No statement by him survives, so we have only the evidence of Gregory’s letter, which tells us that Serenus broke and threw from the church “images of holy persons.” These may have been icons, painted or sculpted images of a single holy figure, such as the image of Christ that Augustine brought on the mission to England. None of the surviving Roman icons from this period happen to depict Christ, but a Christ icon from the eastern Mediterranean gives us an idea of what Augustine’s painting looked like [1]. This panel (Bede’s “board”) was probably made in about Gregory’s era, likely in Constantinople, the Byzantine imperial capital. It escaped the almost universal destruction of images that occurred in Byzantium during the iconoclasm of the eighth and ninth centuries because it was (and is) preserved at the remote monastery on Mt. Sinai in Egypt.

Portraits of important people, such as the emperor or the revered dead, had been made in the pre-Christian Roman world. It was not altogether surprising, then, that Christians adopted the practice for images of their ruler, Christ, and their revered dead, the saints. The cosmopolitan audience in Marseilles would certainly have been familiar with images like the Sinai Christ icon and would have understood its pictorial language, for it was a language that had been current in the Mediterranean for more than a millennium. Marseilles, the oldest city in France, was founded by Greeks in about 600 B.C.; later, it had become fully Romanized and was a central city of the Empire. Paintings like the Christ icon are illusionistic: They are meant to resemble the things they depict. The purpose of pagan funerary portraits and Christian icons was to keep present those who were dead and gone. Illusionistic art depends on establishing a confusion between the representation, the painting or the sculpture, and the thing it represents. This confusion is the magic of this kind of art, but, construed less positively, it is also the root of idolatry. The iconoclast Serenus was probably defending against the idolatrous potential of such images by destroying them.

Another Gregory, also a bishop (this time of the central French city of Tours) and a contemporary of Serenus, provided direct evidence of sixth-century viewers mistaking an image for what it represents. He told the following story about an icon of Christ:

After a Jew had often looked at an image of this sort that had been painted on a panel and attached to the wall of a church, he said: “Behold the seducer, who has humbled me and my people!” So, coming in at night, he stabbed the image with a dagger, pried it from the wall, concealed it under his clothes, carried it home, and prepared to burn it in a fire. But a marvelous event took place that without doubt was a result of the power of God. For blood flowed from the wound where the image had been stabbed. This wicked assassin was so obsessed with rage that he did not notice the blood. But after he had made his way through the darkness of a cloudy night to his house, he brought a light and realized that he was completely covered with blood. At dawn the Christians came to the house of God. When they did not find the icon, they were upset and asked what had happened. Then they noticed the trail of blood. They followed it and came to the house of the Jew. They searched carefully for the panel and found it in a corner of a small room belonging to the Jew. They restored the panel to the church; they crushed the thief beneath stones.4

This distasteful tale is both anti-Semitic and unbelievable. But it is also telling. The Christian bishop Gregory of Tours takes the existence of images for granted. He knows that because of their reading of the Second Commandment, Jews did not have such images, and he imagines that they would find them fascinating. Most important, Gregory’s story assumes a perfect identity between the image of Christ and Christ himself. The painting bleeds when stabbed, just as Christ would. The real Christ, of course, had long since ascended to heaven, so the image is the only available surrogate; thankfully, it is a perfect one.

Gregory the Great was surely no proponent of idolatry. But he saw the value of illusionistic images for providing a focus for Christian faith, especially if they were regarded as stand-ins for the absent Christian god and saints—hence his condemnation of Serenus’s iconoclasm and his decision to equip Augustine with pictures for his mission to England. But an image that functions one way in one context can operate very differently in a different context. I have considered how the Christ icon would have been received in Mediterranean Marseilles in the year 600; what about in far-away Thanet? Britain had been the last part of western Europe to be added to the Roman Empire and was the first to be lost. By the time of Augustine’s mission, such elements of the Roman heritage as the Latin language or illusionistic images had been long forgotten or actively suppressed by the invading Saxons. The visual culture in Britain was very different from that of Rome or Marseilles.

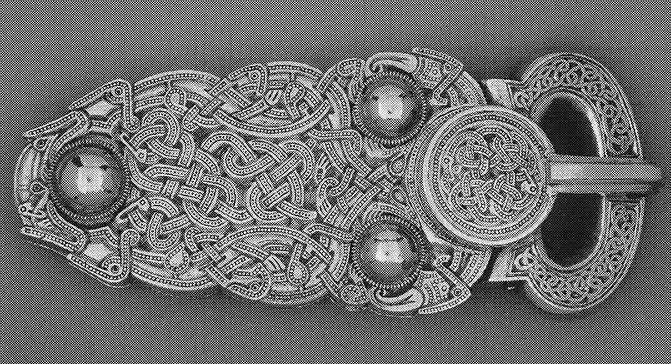

Around 625 a powerful Anglo-Saxon noble, perhaps a ruler, was interred in eastern England in a ship placed in a huge burial mound. Excavated in 1939, mound 1 at Sutton Hoo, as the place is now known, is one of the most remarkable archaeological finds of the twentieth century [2, 3]. The Sutton Hoo grave goods, of exceptional richness and technical virtuosity, are almost precisely contemporary with the Christian mission to England, but they show almost no sign of having been touched by that mission, even though Sutton Hoo is not far from Thanet. They are artifacts of the pagan, oral culture of the Anglo-Saxons, a culture forever changed after contact with the literate Mediterranean Christians. Mediterranean culture was not completely unknown to the ruler interred at Sutton Hoo; buried with him were a silver plate stamped with Byzantine imperial control marks and a selection of gold coins from Gaul.

2 Shoulder clasp from Sutton Hoo. Southern England, c. 625. London, British Museum. Photo: The British Museum

3 Belt buckle from Sutton Hoo. Southern England, c. 625. London, British Museum. Photo: The British Museum

But the Sutton Hoo burial is striking for the absence of Christian artifacts. Instead, we find such accoutrements of a warrior king as a helmet and scepter and spectacular pieces of jewelry, including a shoulder clasp for a cloak and a belt buckle. The primary decoration of the shoulder clasps is made of thin slices of garnet laid over gold foil scored with patterns to reflect the light. A special checkerboard glass of black and blue contrasts with the predominating gold and red. The aesthetic of pattern and decoration governs both the figurative scenes (the grazing boars on the shoulder clasps and the animal-headed interlace on the belt buckle) and such purely ornamental areas as the rectangular central panels on the shoulder clasps and the loop of the belt buckle. Although the pieces from Sutton Hoo are lavish, they are also small; the art of the Anglo-Saxons was portable and secular. This was the visual world that Augustine’s missionaries entered.

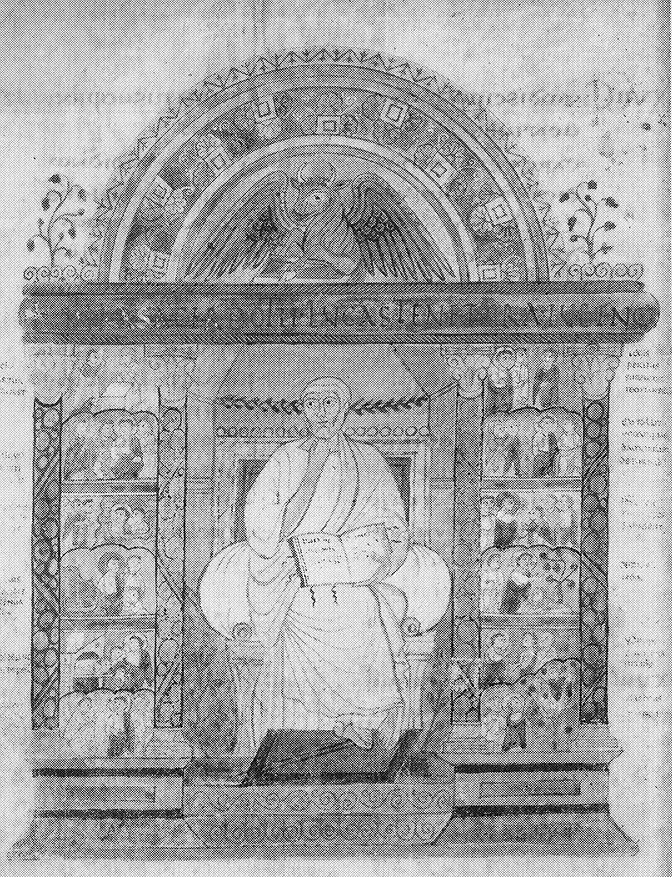

We do not have the “likeness of our Lord and Saviour painted on a board” brought by the missionaries. Bede also wrote, however, that Gregory equipped Augustine with “many books,” and by remarkable chance, it appears as if one of these has survived. Medieval tradition connected a gospel book, then preserved in the English city of Canterbury, with Augustine, who founded the church there [4, 9]. Since the manuscript was made in Italy late in the sixth century, there is every reason to think it is one of the books Gregory sent with Augustine. Even if it is not, the Gospels of St. Augustine (as the manuscript is now known) must be very close indeed to the kinds of books Augustine had with him on the mission. Each of the four gospels was preceded by a portrait of the evangelist, the gospel’s author. Only one of these remains; it depicts Luke, seated in a contemplative pose with his gospel open on his lap [4]. In the arch above Luke is an ox, the symbol associated with him. To the left and right are small scenes from the life of Christ, the story told in the gospel.

4 Luke. Gospels of St. Augustine. Italy, probably Rome, late sixth century. Cambridge, Corpus Christi College, MS 286, fol. 129v. Photo: The Master and Fellows of Corpus Christi College, Cambridge

Parts of England had been converted to Christianity in late antiquity, but the Saxon conquest of England in the fifth century completely suppressed the religion in Britain. It also suppressed literacy, for the Saxons, like all of the invading barbarians, had no written language. Theirs was an oral culture. With Augustine’s mission, reading and writing were brought back to the British Isles. This should not be construed as contact between a high, literate Mediterranean culture and a low, illiterate Saxon one. Literacy and superior culture do not necessarily go hand in hand. But there is a crucial link between Christianity and literacy, for Christianity, in contrast to either Roman or Germanic pagan religion, is a religion of the book; it possesses a written record of divine revelation. The importance to Christians of the word is clear in the first sentence of the Gospel of John: “In the beginning was the Word, and the Word was with God, and the Word was God.” A little later, John describes Christ’s incarnation, his arrival on earth, as “the Word made flesh” (John 1:1, 14). John wrote in Greek and used the rather abstract Greek word logos (“thought, mind”), which Jerome’s Vulgate literally rendered into Latin as verbum, “word.” This translation gave the concrete word a special place in Latin Christianity.

The Gospels of St. Augustine are one expression of that word. But the manuscript also contains images. What is their function? In his letter to Serenus, Gregory wrote that pictures substitute for the sacred word, allowing the illiterate to read what they cannot read in books. The pope thought images were especially important as a too...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Half title

- Title

- Copyright Page

- Dedication

- Acknowledgments

- Contents

- Illustrations

- Introduction

- 1 Books for the Illiterate?

- 2 Art in the Service of the Word

- 3 Books for the Illiterate?

- 4 The Crisis of Word and Image

- 5 Inscriptions and Images

- Conclusion

- Notes

- Further Reading in English

- Index