- 172 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

This book is a beautiful and moving personal account of the Ainu, the native inhabitants of Hokkaid?, Japan's northern island, whose land, economy, and culture have been absorbed and destroyed in recent centuries by advancing Japanese. Based on the author's own experiences and on stories passed down from generation to generation, the book chronicles the disappearing world—and courageous rebirth—of this little-understood people. Kayano describes with disarming simplicity and frankness the personal conflicts he faced as a result of the tensions between a traditional and a modern society and his lifelong efforts to fortify a living Ainu culture. A master storyteller, he paints a vivid picture of the ecologically sensitive Ainu lifestyle, which revolved around bear hunting, fishing, farming, and woodcutting. Unlike the few existing ethnographies of the Ainu, this account is the first written by an insider intimately tied to his own culture yet familiar with the ways of outsiders. Speaking with a rare directness to the Ainu and universal human experience, this book will interest all readers concerned with the fate of indigenous peoples.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Our Land Was A Forest by Mark Selden,Kayano Shigeru in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Politics & International Relations & Regional Studies. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

Our Nibutani Valley

THE AZURE HORIZON spreads in all directions, not a cloud in sight. The pine grove on the opposite shore of the Saru River is dark, but everything else in the vast landscape is pure white, covered with snow. The first time southerners see this Hokkaidō winter scene, they are likely to feel it would somehow be wrong to step into it. I myself felt such reluctance when I first went south and faced the grass that everywhere made the earth green.

Surveying the strikingly clear sky and the distant, dark pine grove across the river, I made my way over the bright snow to pay a visit to the ailing Kaizawa Turusino.

Standing in front of the old woman's house, I noticed a hureayusni decorating the upper right corner of the entrance. Hureayusni, or a branch of raspberry, was used as a charm to ward off colds. When I was a child, if word spread that a cold was making the rounds of a nearby village, every Ainu family put up raspberry branches either at the entrance of their reed-thatched home or by a window.

Turusino's house, like all Ainu homes these days, was a modern cement-block building that resists the cold. Yet this woman in her nineties was unhesitatingly carrying out this long-forgotten custom. The sight of that single branch carried me back forty years to my childhood.

In the early 1930s our Nibutani home was in the distinctive Ainu style, with a wood frame and a roof of thatched reed layers. The boards that served as walls, nailed on from the outside, were just 1 centimeter thick, and they were so warped that a hand could easily fit between the slats. So as winter approached, my mother and older sister prepared large amounts of glue with which to paste sheets of newspaper inside, hoping somehow to keep the snow and wind from blowing in.

I have a photograph of Nibutani in winter taken quite a bit later, in 1939, by the Italian ethnologist Fosco Maraini. As it shows, my home was just a single building without any food storage hut or tool shack; all that stood next to the house was an outhouse. It was the chilly dwelling of the poor.

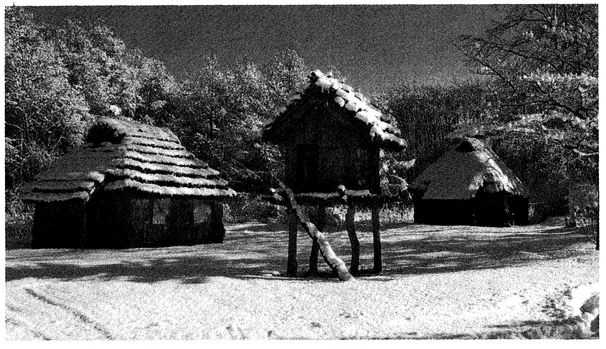

In Ainu a house is called ciset, from ci (we) and set (floor to sleep on). The roofs and walls of the houses shown here, restored for the Nibutani Museum of Ainu Cultural Resources, are made of thatch, which keeps the rooms unexpectedly warm.

But outside of it we children played to our heart's content, racing around in the snow and sledding. Although we wore long underwear, split at the thighs, all we had on top were extra layers over our summer kimonos. If in my excitement I slid down too steep a hill, my kimono would flap open. The snow would come in through the slits of my long underwear, leaving me gasping for breath as it fell onto my penis. As I forgot myself in our games, my hands would stiffen up, and my penis, small enough to begin with, would shrink to the size of a kidney bean.

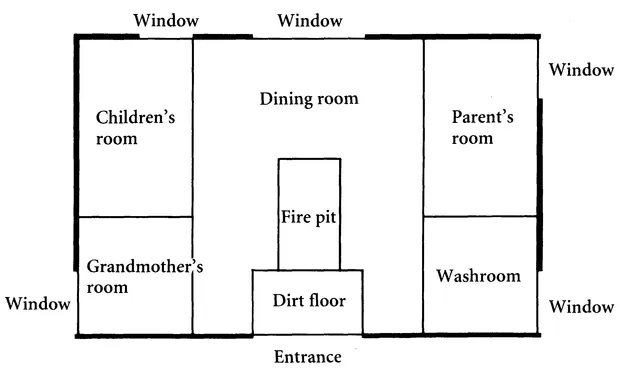

The plan of the Kaizawa house

That was when I would finally miss home. Then I would run with all my might, warming my hands by putting them in my mouth or blowing on them. The moment the house came into sight, I would burst into tears. My mother, hearing me blubbering, would come out of the house and brush off the snow frozen onto my rear end or the hem of my kimono. She would then take my bright red, icy hands inside her robe and warm them between her breasts.

At that time my family consisted of nine members: my grandmother (born in 1850), my parents, an older sister, two elder brothers, myself, and two younger brothers. It was a rather hectic household, all of us crowding into a space of about 40 square meters.

We had a fire pit in the floor about 90 by 180 centimeters. In each of the two corners closest to the master's seat was a sunkenstump 10 centimeters in diameter. These stumps of catalpa, the bark still on, were my father's carving stands, and it was there that he made the many tools we needed in daily life. The tables wore down after several years of use, so Father would pull them out of the fire pit and take them to the altar outside the house. There he would lay them out with millet and cigarettes, offering prayers along the lines of "Please take these gifts back to the land of the gods." The new stumps were installed only after this ritual was performed.

A fire shelf hung above the fire pit. It was about the same size as the pit and had two functions. It ensured that sparks from the fire would not rise to the roof and set it aflame, and it served as a drying shelf for stalks of millet. The shelf was just the right height for a seven-year-old child to bump his head against, and around that age, when I stood up suddenly, I often did hit my head. My grandmother and parents would laugh, saying, "Good, good, it means you're growing. It's just as painful for the shelf. Comfort it by blowing on the spot where you bumped it." I would fight against the pain and, holding back my tears, blow earnestly on the shelf where I had run into it.

My grandmother, too, always sat in a fixed place. It was at the center of one edge of the fire pit, to the right of my father's seat. In front of her in the pit stood a kanit, a divided stick for winding thread. As Huci (Grandmother) wound the thread she had twisted with her fingertips onto the spindle, she would relate Ainu folktales, called uwepekere, to us grandchildren. Of course, she told them in Ainu.

I was her favorite, and Huci would start with "Shimeru" (she could not pronounce "Shigeru"). Once I answered, she would slowly start the tales, never once stopping her work at the spindle. There was a great variety of stories, interwoven with practical bits of wisdom for carrying out daily activities and lessons for life: One must not arbitrarily cut down trees, one must not pollute running water, even birds and beasts will remember kindnesses and return favors, and so on. One of the most often-repeated tales was about a child who was considerate of the elderly, praised by other people and the gods, and grew up to become a happy and respected adult.

In addition to the uwepekere, Huci also told us many, many kamuy yukar, or tales in verse about the Ainu gods. A god dwells in each element of the great earth mentioned in these tales, she would tell us, in the mountains off in the distance from Nibutani, the running waters, the trees, the grasses and flowers. Those gods looked just like humans, spoke the same language, slept at night, and worked by day in the land of the gods. As a child, I trustingly accepted as truth these tales about the gods.

Huci died in 1945 at the age of ninety-five. She had been a superb personal tutor when I was growing up, and it is thanks to her that I speak fluent Ainu and came to take pride in my ancestry. One day, when I was four or five years old, we were walking to the home of relatives about 2 kilometers away. As we approached the Kenasipaomanay, a little creek below the Nibutani communal graveyard, Huci called out, "Kukor son ponno enter" (Grandson, wait a moment for me).

As I stood still, she put aside her cane, sat down at the edge of the creek, and removed her black cloth headdress. Washing her hands and face in the creek, she turned to me and said, "Wash yourself off, too, Shimeru." When I did as she told me, she impressed upon me, young as I was, "You're going to grow up, and your hues will die. Whenever you pass this creek after I'm gone, I want you to remember that this is where you washed with your huci."

Nowadays, the roads around Kenasipaomanay are completely paved, and not a trace of the landscape back then remains. Even fifty years later, however, I always recall my grandmother when I pass by that area. I can thus say that her wish to live on in her grandson's heart, even after she was gone, has been fulfilled.

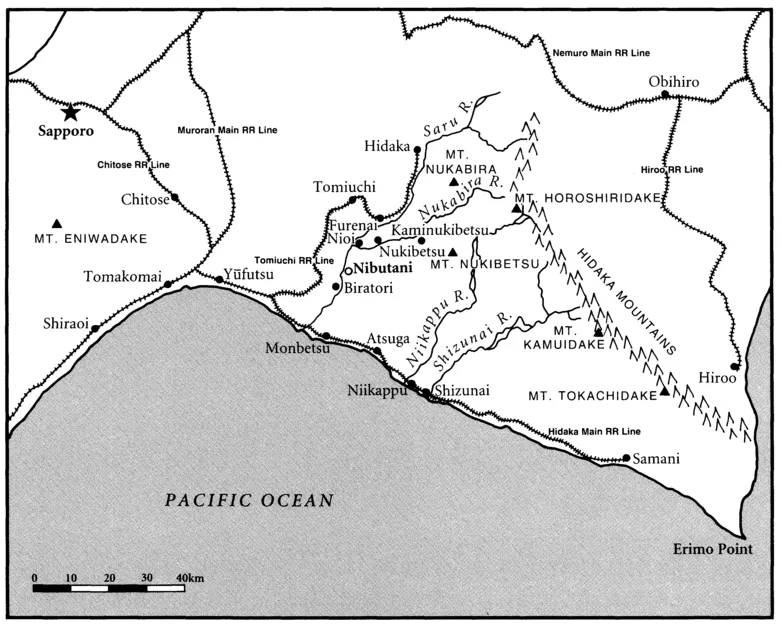

Detail of south-central Hokkaidō

This Nibutani, where I was raised in material poverty yet with spiritual wealth, is in the town of Biratori, located in the Saru region of Hidaka county, Hokkaidō.1 From Tomikawa Station on the Hidaka main line, which runs along the southern shoreline from Tomakomai to Erimo on the national railway, it is about 20 kilometers inland by National Highway 237. This is the warmest region of Hokkaidō, with the least snowfall. The Saru River flows near here, and rice paddies abound. In the past, salmon were plentiful in the river, and in the nearby mountains there were deer and hare.

The Ainu had settled long ago in the Saru River region, with its mild climate and rich supply of food, dotting the landscape with their communities. I believe it is to the Saru that Ainu culture can trace its origins, for the kamuy yukar state that the river is the land of Okikurmikamuy. This is the god who taught folk wisdom to the Ainu: how to build houses, fish, raise millet, and so forth.

We Saru River Ainu prided ourselves on being from the land where the god Okikurmikamuy was born. Whenever we greeted Ainu from neighboring hamlets, we first identified ourselves in the following manner: "I am So-and-so, living and working in the village to which Okikurmikamuy descended from the heavens and taught us our folk wisdom." The other person would take a step back and welcome us respectfully, replying, "Ah, you're So-and-so of the village where the god Okikurmikamuy lived."

It was not until recently that I discovered the origins of the name Nibutani, which lies at about the midpoint of the Saru River. An acquaintance by the name of Nagai Hiroshi brought me an 1892 map on which the valley and its surroundings were labeled Niputay, which must come from nitay. Nitay means woods, forest, jungle. It was this map that finally made me realize the evolution of the Japanized name, Nibutani.

I have also encountered other proof to support my belief that Nibutani was a richly wooded area. About 6 kilometers from Nibutani, in the township proper of Biratori, there is a buckwheat noodle shop called the Fujiwara Eatery. Fujiwara Kan'ichirō, from the generation preceding the shop owners, first came to Biratori as a lumber dealer. He used to tell me, "I've logged all over, but the katsura in Nibutani were the best in Hokkaidō. It wasn't unusual to find trees 2 meters thick. They were so fine I once had a sawyer cut out a section for me to make a table." Even now, that impressive surface, made from a single piece of wood 150 centimeters wide, graces a table in the Fujiwara Eatery.

With just a glance at that piece of katsura, I—a woodcutter for twenty years—can still conjure up images of the dense woods in the mountains behind Nibutani: It was a forest of katsura, with herds of deer roaming through it. Whenever the Ainu needed meat, they entered the woods with bows and arrows and hunted as many deer as they desired. Sometimes they made sakankekam, or dried venison, and stored it. And in the Saru River, whose pure water flows beneath the mountain with its beautiful katsura woods, salmon struggled upstream in the autumn. The Ainu caught only as many salmon as they needed and, removing the innards, split the fish open to dry or smoked them for later use. Long before my time, Nibutani was such a fertile region.

During the Edo period, however, the shamo (mainland Japanese)2 came into the area and, finding the Ainu living in this vast and rich landscape, forced them to labor as fishermen. Then in the Meiji era the shamo started taking over on a larger scale. (I expand on the history of the oppression of the Ainu in later chapters.) Ignoring the ways of the Ainu, who had formulated hunting and woodcutting practices in accordance with the cycles of nature, the shamo came up with arbitrary "laws" that led to the destruction of the beautiful woods of Nibutani for the profit of "the nation of Japan" and the corporate giants. With this, half of the Nibutani region ceased to be a land of natural bounty.

1. Hokkaidō is divided into fourteen counties.

2. Shamo is from a Japanized pronunciation of the Ainu word sam (side, neighbor).

2

The Four Seasons in the Ainu Community

I GO...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title

- Copyright

- Contents

- List of Illustrations

- Foreword

- Translators' Note

- 1. Our Nibutani Valley

- 2. The Four Seasons in the Ainu Community

- 3. My Grandfather, a Slave to the Shamo

- 4. Following Forced Evacuation

- 5. A Long Absence from School

- 6. My Father's Arrest

- 7. An Adolescence Away from Home

- 8. Realizing My Dream of Becoming a Foreman

- 9. Lucky Is the One Who Dies First

- 10. The Teachings of Chiri Mashiho

- 11. Making the Acquaintance of Kindaichi Kyōsuke

- 12. Building the Museum of Ainu Cultural Resources

- 13. As a Member of the Ainu People

- Epilogue

- Glossary

- About the Book and Author