eBook - ePub

Cannibal Culture

Art, Appropriation, And The Commodification Of Difference

Deborah Root

This is a test

- 256 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Cannibal Culture

Art, Appropriation, And The Commodification Of Difference

Deborah Root

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

The book examines the ways Western art and Western commerce co-opt, pigeonhole, and commodify so-called "native experiences." It raises important and uncomfortable questions about how we travel, what we buy, and how we determine cultural merit.

Frequently asked questions

How do I cancel my subscription?

Can/how do I download books?

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

What is the difference between the pricing plans?

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

What is Perlego?

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Do you support text-to-speech?

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Is Cannibal Culture an online PDF/ePUB?

Yes, you can access Cannibal Culture by Deborah Root in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Arte & Arte general. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

I

Fat-Eaters and Aesthetes: The Politics of Display

A few years before Cortés landed on the coast of Mexico, evil omens began to appear in the capital city of Tenochtitlán that warned of the imminent arrival of the Spaniards and the destruction of the Aztec empire. One omen was a strange, ashen-colored bird fished out of the lake surrounding the city. This bird wore a mirror in its forehead in which could be seen the night sky and certain constellations. As Motecuzoma gazed into the mirror, the black starry night dissolved to show strange warriors coming toward him, riding deer and fighting among themselves. When the king asked his magicians to look into the mirror, both the image and the bird suddenly disappeared.

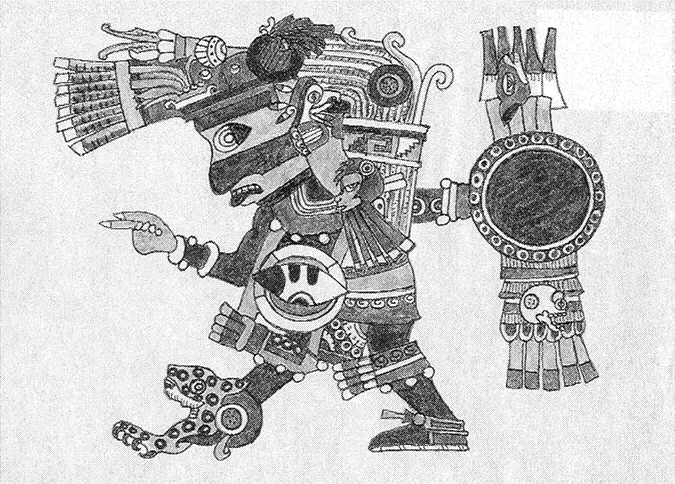

What made this omen so particularly disturbing to Emperor Motecuzoma and so clearly a portent of the destruction of the city? The appearance of the bird meant it was a message from Tezcatlipoca (see Figure 1.1) to his subject and surrogate, Motecuzoma. Tezcatlipoca is the Smoking Mirror, the black god of the north, of night, and of magicians and robbers. He sometimes appears as a handsome, flute-playing youth and sometimes as a jaguar. Smoking Mirror controls the forces of death and destruction and was referred to in Tenochtitlán as “the enemy on both sides” and “the tyrannical one,” yet he also creates and bestows wealth and dignity. The presence of Tezcatlipoca saturates the institutions of kingship and human sacrifice in Aztec Mexico.

The story of a doomed king gazing into a mirror recalls the demise of another ruler, the god-king Quetzalcoátl-Topilzín of Tula, the Toltec kingdom on which the Méxica people, or Aztecs,1 based their legitimacy and whose history and mythology they appropriated. Here, Quetzalcoátl’s brother fomented a revolution in order to impose human sacrifice and militarist ideals on the Toltec city. The evil brother was, of course, Tezcatlipoca the Smoking Mirror, and he bested his brother by a ruse: through trickery and malice, Tezcatlipoca made his brother look into a mirror, and the sight of his face so shocked and horrified Quetzalcoátl that he became drunk and committed incest with his sister. In shame Quetzalcoátl was forced to flee the city, leaving it to Tezcatlipoca and the forces of human sacrifice and militarism. Bad omens began to announce Tula’s impending collapse. In the cyclical histories of Méxica cosmology the fall of Tula mirrored the imminent fall of Tenochtitlán, with Tezcatlipoca appearing as the mocking destroyer.

Figure 1.1 Tezcatlipoca (after Codex Borgia, D. Root)

Tezcatlipoca plays a double game. His ambivalent relation to his subjects exemplifies how despotic authority operates and seduces again and again. No matter how power is represented, no matter how often it appears as something kindly, benevolent, or beautiful, Tezcatlipoca waits to hand us the mirror, revealing the connections between wealth and death, power and disaster. In the contemporary imperial systems of the Western tradition violence and beauty continue to go hand in hand, fragments endlessly reflecting each other but all pointing to the scornful hunger of Tezcatlipoca. If the despot is imagined as the sign that all other signs refer to, we can see that the various manifestations of despotic authority are able to devour images as much as human bodies.

The Aztecs recognized that human flesh was necessary to the functioning of the state, and they knew the extent to which violence and the consumption of bodies were immanent to empire. At some point a deal was cut: The Aztecs were allowed to consume the wealth of the people they conquered, but it cost them blood. The Smoking Mirror was very explicit in his demand for blood, and the Aztecs were rigorous in upholding the ceremonies that honored this demand. The sacrificial victim climbed the pyramid to meet the obsidian knife, and after the heart had been cut out of the body and the blood offered to the gods, the arms and legs were distributed to the priests who administered the sacrificial cult. The eating of human flesh was strictly ritualized in Tenochtitlán, and complex cosmological questions regarding the transmutation of matter circumscribed the cannibal ceremonies. At the same time, however, the Aztecs made a point of eating foreign enemies rather than Méxica. It is always someone else’s flesh that is the meal of choice.

Does Tezcatlipoca walk in the West? Does Tezcatlipoca still demand blood in exchange for power? Is it possible that, despite the European claim to rationality and the ideal of the democratic polis, violence and cannibalism have a ceremonial function here similar to that of the Aztec state? Elaborate systems of representation distract attention from the extent to which our system also depends on the ritualized killing of human beings. The Western powers launched a war in the Persian Gulf and bodies were consumed amid a ceremonial display and repetition of images of the Western family, of individual heroism, and of cultural self-congratulation. “Baghdad lit up like a Christmas tree,” one pilot said, thus articulating a display of power that was more exhilarating than negotiations or sanctions could ever be because it aestheticized the idea of dead bodies. Violence became something beautiful. The Christmas tree image elides what was occurring on the streets of Baghdad as the bombs fell, and all we are left with is the pilot’s pleasure of mastery. The words of the U.S. pilot offer no more than a glimpse of how cannibal power works, but they promise so much more. The smoking mirror offers a dream of plentitude and perfection, but as Tezcatlipoca and Louis Althusser have shown in their different ways, the image of the face of power can operate only as another ruse.

Different societies approach questions of power and representation differently, and some are much more suspicious of authority than the Western tradition is and have developed techniques to contain the representation of power. Some societies see power as quite dangerous and unattractive (although always interesting).2 Others bring the problem right out into the open and give power a name, which can be another version of the same thing. In recognizing that power can be named as such, we can see how the Méxica stories illuminate the nature of power, which remains behind the mirror in the Western tradition because we are unwilling to gaze into its face. The Aztec metaphor suggests another way to approach Western ambivalence about representation and imperial authority. It is worth paying attention to Tezcatlipoca because he demonstrates that the state is and always has been a cannibal monster continually seeking flesh to consume. Let us return to the story of the two brothers.

That the fall of the Toltec state appeared in the Aztec writings as the result of a conflict between enemy brothers was indicative of how destructive the antagonism between these two figures was. Each brother represented a rival view of militarism and human sacrifice—in short, how violence should be organized and represented by the state. I sometimes wonder if these stories suggest that the outcome of the struggle could have been different and that, barring Tezcatlipoca’s treachery, the Méxica could have created a different kind of state, where bodies were not consumed by wars and the sacrificial block. It is important to remember that the expansionist ideals of imperial Tenochtitlán, the economy based on tribute, and the mass human sacrifice of prisoners of war were all instituted and maintained by the military-religious-merchant elites of the city. As in Europe, it was not the hunters, farmers, or ordinary people living in small villages who established the cannibal regimes.

Certainly it was at least in part through the honoring of Quetzalcoátl that people were able to maintain nonmilitaristic ideals within a militaristic economy. Quetzalcoátl was presented as a dupe and victim of sorcery and tricks, yet was always more benevolent and helpful to people than Tezcatlipoca. But the veneration of Quetzalcoátl as the Toltec god par excellence—and as the god of learning, science, and the priesthood—did not change the fact that it was the sorcerer Tezcatlipoca, the Smoking Mirror, who ultimately won. In imperial Tenochtitlán, Tezcatlipoca was elevated to the supreme god and worshiped as Tloque Nahuaque—Master of the Near and the Close—the god who was always there.

Quetzalcoátl, in contrast, was taken up by the priesthood. High priests were given the title of “Quetzalcoátl,” which at first glance seems fitting given the view of the Toltecs as the source of all knowledge and culture and of the figure of Quetzalcoátl as the exemplary Toltec sovereign. Quetzal-coátl’s peaceful reign in Tula (until all the trouble at the end, of course), his identification with the priesthood and with the virtues of harmony, wisdom, and learning, were evoked again and again in the Méxica priestly texts, which seems somewhat contradictory given Quetzalcoátl’s well-known opposition to human sacrifice and the priests’ rather intense dedication to it. The ideals extolled in the Quetzalcoátl literature were nevertheless presented as antithetical to the sorcery and discord wrought by Tezcatlipoca, and the Méxica writings were careful to distinguish between the two figures and the qualities and values with which each was associated.

Because of the constant emphasis on the differences between the two brothers, it is easy to forget that Quetzalcoátl was a ruler as well as a priest, which meant that he maintained political sovereignty in Tula, with all the hierarchy and violence implied by an institution of royal authority. The priestly ideal personified by Quetzalcoátl occluded his despotic function or, rather, purified and rendered benign the idea of the despot or supreme lord. Quetzalcoátl became the ruse of imperial power, appearing as what the state was at its best and what kings at their best were capable of offering the people. But we know better. The despotic face of the wise king was revealed by Tezcatlipoca, who brought about the fall of Tula by displaying to Quetzalcoátl his face: “Then he gave him the mirror and said: ‘Look and know thyself my son, for thou shalt appear in the mirror.’ Then Quetzalcoátl saw himself; he was very frightened and said: ‘If my vassals were to see me, they might run away.”’3

Tezcatlipoca’s sorcery is stronger than Quetzalcoátl’s arts and sciences because it is capable of revealing the despot to be not the benign face of Quetzalcoátl but the fearsome face of the enemy on both sides. Illusions fall down, all is revealed, and the face in the mirror is that of the sign all other signs refer to: power. Tezcatlipoca teaches that the state operates and maintains its authority through violence and terror. The sovereign of Tenochtitlán himself recognizes this and indeed becomes king by revealing Tezcatlipoca’s absolutist demands and by enacting a performance in which this is displayed for all to see. The human sovereign’s relationship to the deity is one of abjection and self-abasement before a greater power, here the despotic authority of the god. In the formal speech made by the Méxica king to Tezcatlipoca on the occasion of his ascension to the throne, the king says, “O master, O our lord, O lord of the near, of the nigh, O night, O wind, thou hast inclined thy heart. Perhaps thou hast mistaken me for another, I who am a commoner, I who am a labourer. In excrement, in filth hath my lifetime been—I who am unreliable, I who am of filth, of vice. And I am an imbecile.”4

The device of making the sovereign say such things publicly was instituted, not only I think, to underline his humility before the god but also to absolutize the idea of despotic authority in itself. The king’s willingness to express his subordination becomes a way to represent the broader concept of formal authority, and the point emphasized in the speech is that the symbolic system must be ordered hierarchically, with a chain of command in which everyone is implicated. Even a sovereign has a master. This is what is important, not any particular god or ruler.

The story of the two brothers explains despotic violence and militarism while seeming to maintain an ideal of the benign state, but the triumph of Tezcatlipoca functions as a recognition that political authority is always underlain by chaos and death.

The other principal gods, and their functions and activities, turn out to be different guises or aspects of the Smoking Mirror. The god of war, Huitzilopochtli, is revealed as the blue Tezcatlipoca of the south; the flayed god, Xipe Totee, is the red Tezcatlipoca of the east, and even the brother-enemy Quetzalcoátl becomes the white Tezcatlipoca of the west. Lamenting the fate of the unfortunate Quetzalcoátl distracts us from the extent to which the ideals associated with Tezcatlipoca’s triumph—that is, the ideals of the state, of militarism, and of human sacrifice—were affirmed in the Méxica cities.

One of the attributes of Tezcatlipoca is invisibility—in some paintings he is represented only by footprints—and this ability to become invisible at will increases his power and fearsomeness. Indeed, even though the name Tezcatlipoca is generally translated as “Smoking Mirror,” a more accurate rendition would be “The Smoke That Mirrors.” Obsidian mirrors were used for divination by the Méxica (and the Aztec mirrors that reached Europe after 1521 were used for the same purpose by magicians such as John Dee and Nostradamus). Magicians gazed into the mirror and waited for images to form. The sense of a smoke that mirrors is suggestive of a double quality of veiling and revealing through reflection; the smoke both obscures and reflects the image of the inquirer. The face of power is never fully revealed but always veils itself. And here it is the god himself, the despotic deity Tezcatlipoca, who reflects the image of the people and of the priests who seek knowledge of the future and of the affairs of state.

Tezcatlipoca’s mirror has a name; it is called “The Place from Which He Watches.” The invisible god sees all and knows all. The shock and horror provoked in both Quetzalcoátl and Motecuzoma by the presence in the mirror are not difficult to understand—both figures were reminded that the watching eye of power was on them, that the despotic gaze was everywhere, even on the supreme leaders of the state. They were also reminded that they, too, reflected the face of the despot, a truth that Quetzalcoátl found impossible to bear. And this despotic gaze implies a destructive quality that both observes and reflects the power of kings.

I chose (or perhaps appropriated) the example of the two Mexican brothers to illustrate something that can be overlooked in Western culture: Power is never benign. When the mask of the good king is stripped away, the face underneath is always that of Tezcatlipoca, whether he is called Good Queen Bess or John F. Kennedy. Tezcatlipoca—or at least his manifestations in the human world—is a cannibal, an entity that needs nev-erending streams of blood and human bodies to consume and whose desires are organized around death. In societies with hierarchies that control bodies and determine which ones will live and which ones will die, there is always some spectacle of violence (even if it sometimes takes place behind closed doors, with only a few witnessing or partaking). Most sacrificial spectacles, which take explicit and implicit forms, display and symbolize the link between power and representation for all to see. All are implicated, and people are kept in line. Power swallows life.

The story of the two brothers shows us that the Méxica recognized the nature of a hierarchical political system, but once social and religious power was concentrated in the hands of an elite, the system became extremely difficult for ordinary people to change, even assuming they wanted to do so. The Méxica sacrificial system is not, I think, an anomaly among hierarchical social systems, which is why it can illuminate the blind spots and failures in the Western tradition. The specific form this system took— the pyramids, the lines of prisoners awaiting the sacrificial block—was more explicit than many others about its need to consume human bodies and to display this ability to consume for all to see. I am not describing the Méxica state as a cannibal system in order to separate Aztec Mexico from the equally cannibalistic European social orders and derisively mark it as “barbarian” (or some such epithet). Much like the system that has come to dominate the West, the Méxica symbolic and political economy had to feed off violence in order to reproduce and survive. The Aztecs understood the ambivalence of power, its ability to simultaneously seduce and demand, and its facility in taking on a life of its own. The particular manifestations of imperial authority (as demanded by Tezcatlipoca) became extremely difficult to divert from the cannibal path once it had reached a certain point. And, again, some people benefited from such a system. The story of the two brothers also shows that Tezcatlipoca is perhaps easier to recognize, if not control, if he is understood within a sacred order.

Because most Spaniards who invaded Mexico in the sixteenth century refused to look squarely at the implications of power, they could not tolerate the explicitness of the Méxica state’s organization of violence and mass death. For example, in Tenochtitlán prisoners of war were sent to the sacrificial pyramids, while in Paris in the same years thousands were slaughtered in the streets in the Saint Bartholomew’s Day massacre. The European state was—and is—as much a cannibal as the Aztec, but mass death in Europe tends to be classified as an accidental phenomenon rather than as something intrinsic to the functioning of the system. Despite example after example of Western atrocities, it is always someone else who is the cruel and pitiless barbarian.

These harsh words are not intended to negate the many critical streams in European thinking that have addressed questions of violence and power and, in particular, the ambivalence these are able to generate. But I think we must face the possibility that something is dreadfully wrong with society and that this is somehow connected to the bloody history of Western culture, a bloodiness that surpasses all others, including the Aztecs and their human sacrifice. But is it even possible to look at our cannibal nature? We remember the consequences of looking in Tezcatlipoca’s mirror— Quetzalcoátl lost his power and had to leave the city.

The Aztec state rendered absolutely and unmistakably explicit the nature and consequence of a hierarchical and imperial social order, something that is prettied up in the Western tradition with notions of “civilization,” the aesthetics of high culture, and the Greek polis as the source of democratic political organization. This disavowal continues to obtain today. The Méxica are presented as a horrific, incomprehensible society where violence was totally out of control—unlike us. European writing about Aztec society focuses almost exclusively on human sacrifice, which is described in such a way as to obscure the links among the different versions of violence from above. (A great deal of perplexed head-shaking goes on as Western academics attempt to account for Aztec state institutions; Claude Lévi-Strauss refers to the Aztecs as “that open wound on the flank of Americanism.”5) This refusal has its consequences in t...

Table of contents

Citation styles for Cannibal Culture

APA 6 Citation

Root, D. (2018). Cannibal Culture (1st ed.). Taylor and Francis. Retrieved from https://www.perlego.com/book/1598377/cannibal-culture-art-appropriation-and-the-commodification-of-difference-pdf (Original work published 2018)

Chicago Citation

Root, Deborah. (2018) 2018. Cannibal Culture. 1st ed. Taylor and Francis. https://www.perlego.com/book/1598377/cannibal-culture-art-appropriation-and-the-commodification-of-difference-pdf.

Harvard Citation

Root, D. (2018) Cannibal Culture. 1st edn. Taylor and Francis. Available at: https://www.perlego.com/book/1598377/cannibal-culture-art-appropriation-and-the-commodification-of-difference-pdf (Accessed: 14 October 2022).

MLA 7 Citation

Root, Deborah. Cannibal Culture. 1st ed. Taylor and Francis, 2018. Web. 14 Oct. 2022.