- 240 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

The growth and expansion of cities and the transition from a rural to an urban society are among the most critical links between population change and economic development. On the one hand, migration is one of the fundamental demographic processes associated with changes in the population of urban places; the changing distribution of population be

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Urbanization And Development by Paul K C Liu in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Sciences sociales & Anthropologie. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

Economic Development and Population Growth

The postwar economic development of Taiwan has been one of the real success stories in the less developed world. Starting from a level not very different from other less developed countries in the late 1940s, Taiwan had achieved a per capita GNP of $3,145 in 1985 which placed it well above the average of $1,850 for "upper-middle-income" countries according to the World Development Report (World Bank, 1987). Although there were several aspects to Taiwan's development, probably the most important was the rapid growth of manufacturing. In 1950, Taiwan was predominantly agricultural with most manufacturing centered on the processing of farm or forestry products. By 1980, one-third of the labor force was employed in manufacturing and the proportion in manufacturing exceeded that of several Western nations such as England, France, Italy, and the USSR.

The economic development and industrialization of Taiwan was accompanied by rapid urbanization. As we shall show in the following chapters, Taiwan was transformed during this period from a largely rural country to one in which the majority of the population lived in metropolitan areas or cities of over 100,000 population. While urban growth has been rapid, it has not been excessive and growth has been spread out both over time and space. While Taiwan has experienced some of the problems associated with rapid growth such as traffic congestion and air pollution in major cities, it has avoided other problems such as widespread urban unemployment and extensive squatter settlements which have plagued many less developed countries.

The relative ease with which Taiwan has progressed through the rural to urban transition, the balanced growth between different regions and between core and peripheral areas, and the adjustment of migrants to urban settings all provide examples for other less developed countries which are still mostly rural. It is our goal to describe the process of urbanization in Taiwan and to explore the determinants and consequences of urbanization both at the aggregate level and the individual level. We will seek to answer both why individual cities have grown and why individuals have moved to these places. We shall investigate the effects of growth on places and individuals. While some of the answers will relate to factors which are unique to Taiwan, many are factors which could be replicated in other settings.

Taiwan's urbanization has been shaped, to a large extent, by the course of economic development and population growth. Before examining the details of the urbanization process, it will be helpful to review the course of development and population growth. What are the factors responsible for Taiwan's rapid development? What has been the history of population growth and how has it been related to development? In the rest of this chapter, we will try to answer these questions.

The Economic Development of Taiwan

Taiwan's successful economic development has received widespread recognition.1 Little (1979, p. 448) states that "Taiwan has a good claim to be ranked as the most successful of the developing countries." Since the early 1950s, Taiwan has been one of four Asian countries to experience sustained and rapid economic growth starting from a low level after World War II without reliance on substantial mineral resources.2 However, two of the others, Hong Kong and Singapore are city states which function partly as international trade centers for products produced in other countries. The other country, Korea, has equalled Taiwan in overall economic growth, but has not done as well in distributing this growth among different regions of the country or sectors of the economy (Lau, 1986).

The growth of Taiwan's economy is briefly summarized in Table 1.1. The most impressive thing about this data series is the regularity of the growth over a long period of time. Although there have been slowdowns in growth, most notably in 1974 and 1982, when growth is averaged over five year periods and adjusted for inflation, it varies only from 6.4 to 10.6 percent per year. The most rapid growth occurred during the period from 1975 to 1980, although it also was high in the early 1950s and during the entire decade of the 1960s.

In addition to the rapid growth in GNP and GNP per capita, Taiwan accomplished a very significant transformation from an agricultural nation to an industrial nation during this period. In 1951, 32 percent of the gross national product was obtained from the primary sector of the economy

TABLE 1.1

INDICATORS OF ECONOMIC GROWTH IN TAIWAN

INDICATORS OF ECONOMIC GROWTH IN TAIWAN

| Period | Average Annual Growth in GNP in Constant 1981 Dollars | Average Annual Growth of Real Per Capita GNP | Average Annual Growth in Consumer Prices | Export as Percent of GNP in Final Year |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1951-55 | 9.7 | 6.0 | 14.3 | 8.3 |

| 1955-60 | 6.7 | 3.1 | 10.5 | 11.3 |

| 1960-65 | 9.5 | 6.1 | 2.4 | 18.7 |

| 1965-70 | 9.8 | 6.5 | 4.4 | 29.7 |

| 1970-75 | 8.8 | 6.7 | 12.2 | 39.5 |

| 1975-80 | 10.6 | 8.4 | 8.7 | 53.0 |

| 1980-85 | 6.4 | 4.7 | 3.9 | 54.5 |

Source: Calculated from data in DGBAS, Quarterly National Economic Trends, February 1986.

(farming, fishing and forestry) and only 24 percent from the secondary sector (mining, manufacturing, utilities and construction). By 1985, agriculture accounted for less than seven percent of the GNP and the secondary sector accounted for 51 percent (DGBAS, 1986, Table 6).

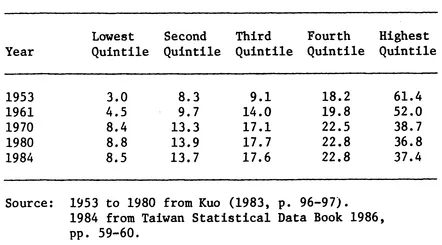

A third important aspect of Taiwan's development is the changes which have occurred in the income distribution. According to figures prepared by Kuo (1983) which are presented in Table 1.2, the share of income received by families in the top quintile of the income distribution declined significantly from 61 percent in 1953 to 37 percent in 1980 while that received by families in the lowest quintile increased from 3 percent to 9 percent. While the income distribution in general became much more equal, the distribution between urban and rural families followed a curvilinear pattern with increasing urbanization. Up to the early 1970s, the share ratio of income between the most rural counties and the largest cities decreased, but thereafter it increased (Kuo, 1983, pp. 109-116). This is contrary to the normal relationship whereby early development tends to increase inequality between urban and rural areas.

TABLE 1.2

DISTRIBUTION OF INCOME AMONG HOUSEHOLDS BY YEAR

DISTRIBUTION OF INCOME AMONG HOUSEHOLDS BY YEAR

Taiwan's rapid economic growth can be divided into three phases, roughly corresponding to the periods from 1949 to 1960, 1960 to 1973, and the period from 1973 to 1985, although the transition dates for these stages are somewhat arbitrary and subject to debate (Gold, 1986). We shall refer to these as the takeoff phase (1949-60), the labor-intensive industry phase (1960-1973), and the industrial upgrading phase (1973-1985).

The Takeoff Phase

The first phase might be referred to as the takeoff phase of development. One of Rostow's criteria for takeoff is that a country without foreign aid should have net investment equal to 10 percent of the national income (Rostow, 1960)3 Kuo (1983:6) points out that if one counts only domestic savings as the source for investment, that this was not reached until 1963, although foreign aid and foreign investment, when added to domestic savings put Taiwan above the 10 percent level throughout the 1950s. Thus foreign aid and investment were important factors in Taiwan's early development.

The United States took a special interest in Taiwan because of its strategic position in the international relations and military strategy for East Asia in the 1950s and early 1960s. Between 1951 and 1965, the United States provided about $ 1.5 billion in economic aid to Taiwan plus additional military aid (Myers, 1986, p. 47). Between 1951 and 1961, U.S. economic aid amounted to about 37 percent of total domestic investment. After 1961, aid as a proportion of total investment declined and ceased altogether after 1968. The economic aid went particularly into supporting infrastructure such as electricity, transportation and communications. While the value of the military aid is hard to assess, if one assumes that because of fears of invasion from Mainland China that Taiwan would have built up the military with its own resources, then the U. S. military aid made it possible for more government resources to be devoted to economic development than would have been possible otherwise (Jacoby, 1966; Scitovsky, 1986, p. 143).

The second important factor in Taiwan's early development was land reform. The Land-to-the-Tiller program was initiated by the government in 1949. The program limited the amount of land which could be held by any one family to a maximum of three hectares and required the transfer of any additional land to tenants who were tilling the land, with payments spread out over ten years.4 About 30 percent of the payment to the landowners was in terms of shares in government industries, so that the program also provided a source of nonagricultural investment (Thorbecke, 1979). As a result of this program, the proportion of cultivators who were owners increased from 36 percent in 1949 to 60 percent by 1957. While many farmers owned only small parcels, they had an added incentive to farm the land intensively and land reform is generally credited with increasing productivity per hectare and with increasing total agricultural production in Taiwan (Kuo, 1983, pp 26- 29). Taken together with other agricultural development policies, land reform helped Taiwan to increase its exports of agricultural products during the 1950s and thus earn foreign currency to pay for imports needed for development.

The third factor which was important in Taiwan's takeoff period was monetary policy. Following a period of hyperinflation in the late 1940s, when prices increased 30 fold, high priority was given to the stabilization of prices and relatively high interest rates (in real terms) were established to keep the money supply from growing too rapidly. As a result, the inflation rate from 1955 to 1960 was held to about 10 percent per year (see Table 1.1) and during the 1960s it was generally on a par with inflation rates in the United States and other Western nations.5 This provided a good climate for investment in new businesses and the relatively high interest rates encouraged individual savings while government policies facilitated the opening of small bank accounts.

The resulting economic growth during the takeoff period was focused on import substitution, both on critical food products such as rice, on producer inputs such as fertilizer and chemicals, and on basic consumer goods such as clothing, footwear, wood products and bicycles. The government's policy of import substitution was carried out through stiff tariffs on certain imported goods and restrictions on some others. While the policy was successful in encouraging local production of these goods, Scott (1979) debates whether a policy of import substitution really helped development or whether it would have been better to promote exports at an earlier stage of development.

By the late 1950s, the government recognized the need to produce more products for export in order to expand its markets and provide a favorable trade balance. At first, exports were mostly agricultural products such as sugar, rice, bananas, teas and canned fruits and vegetables. Between 1952 and 1955, industrial products accounted for only about nine percent of exports (Wu, 1985, p. 10). However, by 1961-65, there was a noticeable increase in the proportion of industrial products to 44 percent of total exports.

The Labor-Intensive Industry Phase

While the government had already begun to promote exports in the late 1950s, this policy was strengthened in the 1960s by providing for rebates on import duties for materials used in the manufacture of exports and by several...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title

- Copyright

- Contents

- List of Tables

- List of Figures

- Foreword

- Preface

- 1 Economic Development and Population Growth

- 2 An Historical Overview of Urban Growth

- 3 The Relationship Between Urbanization and Development

- 4 The Growth of the Taipei Metropolitan Area

- 5 Alternate Responses to a Changing Economy: Migration, Commuting and Rural Industrialization

- 6 The Determinants of Migration to the City

- 7 The Economic Success of Migrants in Taipei

- 8 Living Conditions and Social Life of Migrants in the City

- 9 Implications for Policy and Further Research

- Appendix A: The 1973 Taiwan Migration Survey

- Bibliography