- 192 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Feminism, Objectivity and Economics

About this book

This classic study extends feminist analysis to economics, but rejects setting up an economics solely for women. It is the first full length, single authored book to focus on gender bias in contemporary economics.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Feminism, Objectivity and Economics by Julie Nelson in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Business & Business General. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Part I

THEORY, FEMINIST AND ECONOMIC

1

THINKING ABOUT GENDER AND VALUE

WHAT “GENDER” IS NOT

A frequent popular confusion is to take the word “gender” to mean “about women.” This interpretation is misleading on two counts. First of all, women are not the only sexed people in the world. Men are also sexed; it is only because maleness has often been confused with universality that the implications of male sexual identity have been pushed into the background. Second, (except where the substitution of “gender” for “sex” is done because of squeamishness about the latter word’s possible connotation of sexual activity) “gender” is now used in much scholarly literature to refer to something different from biological sex. Seeking to distinguish between inborn proclivities and socially created stereotypes, feminists have taken over the term “gender” to refer to the latter. While this book takes a feminist viewpoint, in this chapter the term “gender” will be used in a way that also has much in common with the term’s older, linguistic, sense.

In linguistics, gender refers to the way in which many cultures divide words into distinct classes and mark them accordingly. While, masculine/ feminine are common linguistic genders, other classifications such as inanimate/animate can also form the basis for grammatical gender. That is, the emphasis in this book is on the way in which the masculine/ feminine distinction serves as a means of classification undergirding language and thought, rather than how the sex/gender system tends to mold men and women in stereotypical ways. This chapter investigates how gender serves as a cognitive organizer, based on the idea of metaphor as a basic building block of understanding. Without this background, the argument of the next chapter—that current economics is held back by its gender associations—can hardly help but be misunderstood.

This chapter investigates current conceptions of gender, and suggests a way of envisioning gender which does not conflate notions of masculinity and femininity with judgments about worthiness.

THE LINGUISTIC BASE

“The essence of metaphor is understanding and experiencing one kind of thing in terms of another,” as George Lakoff and Mark Johnson say in their work, Metaphors We Live By (1980:5). According to them, and numerous other researchers in the areas of cognition, philosophy, rhetoric, and linguistics, metaphor is not merely a fancy addition to language, but is instead the fundamental way in which we understand our world and communicate our understanding from one person to another (e.g., Ortony 1979; Grassi 1980, cited in Weinreich-Haste 1986; Margolis 1987; McCloskey 1985). Lakoff and Johnson give many examples of how the language we use reflects metaphorical elaborations of more abstract concepts on the foundation of basic physical experiences. Our perception of “up/down,” for example, forms the basis for “good is up, bad is down,” “reason is up, emotion is down,” “control is up, subjection is down,” and “high status is up, low status is down.” Richer meanings can be found in more complex metaphors such as “argument is war” (reflected in language like “win,” “lose,” “defend,” “attack”), “argument is a journey” (e.g., “step by step,” “arrive at conclusions”) or “argument is a building” (e.g., “groundwork,” “framework,” “construct,” “buttress,” “fall apart”).

These metaphors affect our understanding and our action: for example, if we perceive ourselves as engaged in an argument, how we interpret what we hear and how we respond depends in good part on which metaphor we use. Metaphorical understanding is also culturally variable. For example, there could exist another culture that uses the metaphor “argument is dance” and so uses language of esthetics, style and synchronization. All of the above examples are given by Lakoff and Johnson.1 Echoes of a similar understanding of cognition and communication can be found in works that speak about cognition in terms of “webs of connection” (C.Keller 1986), “patterning” (Margolis 1987; Wilshire 1989), “cognitive schema” (Bem 1981), Gestalts, or analogies, instead of “metaphor.” I will use the word “metaphor” loosely, to mean all these things.

One can gain additional insight into the human mind’s way of classifying and understanding by looking at “gender” in the strictly linguistic sense. Corbett (1991) explains that gender systems always have a semantic core, that is, some words for which the meaning of the word determines its gender. This includes direct association, as, for example, in Spanish one finds la mujer (the woman, feminine) and el hombre (the man, masculine). Also included in the semantic core are metaphorical associations, mediated through associations of objects with the sexes through myths and children’s stories or by association with the customary occupations of the sexes. For example, while the English language has only pronomial (pronoun) gender, dogs are commonly considered more masculine than cats in Englishspeaking cultures, perhaps due to images in children’s literature. Some words may take their grammatical gender only formally, from morphological (word structure) or phonological (sound structure) rules, having no relation (even metaphorical) to sex (Corbett). In this book, it will be gender in the metaphorical sense that is primarily of interest, though I will go beyond the strictly linguistic sense to include metaphorical associations not reflected in word structure and to include parts of speech other than nouns. I will also use “gender” somewhat more narrowly than in the linguistic sense, in that I will discuss only metaphors built on the male/female distinction. The key point, however, is that the masculine/feminine distinction serves as an organizing pattern in our minds and language.

GENDER AND METAPHOR

I use “gender,” then, to refer to the cognitive patterning a culture constructs on the base of actual or perceived differences between males and females. Gender is the metaphorical connection of non-biological phenomena with a bodily experience of biological differentiation.

Bodily sexual difference is clearly a salient part of experience starting in early childhood, in most cultures. Yet one of the major breakthroughs in feminist analysis has been the discovery that many (if not most) of the traits assumed to be “essentially” male or female related, in a biological sense, actually have very strong cultural components. Take, for example, the idea that men are more suited for intellectual work than women. The smaller size of the female brain was taken as scientific proof of intellectual inferiority in the nineteenth century (Bleier 1986). While the lack of connection between size and power has since removed this craniometric argument, the undermining of such supposed biological proofs does not necessarily carry with it a cessation of gender attribution. The cultural salience of the idea of women as less intelligent than men may persist in spite of a lack of supporting theory and even in the face of evidence to the contrary.

To say something has the masculine gender, then, is not to say that it necessarily relates to intrinsic characteristics of actual men, but rather to say that it is cognitively (or metaphorically) associated with the category “man.” A male person is biologically masculine; a pair of pants (as on the stick figures that adorn restroom doors) is only metaphorically so. An angular abstract shape may also be understood through the metaphor of masculinity, as contrasted to a curvy abstract shape. Cats are generally considered in contemporary American culture to be more feminine (in disregard of their actual sex), whereas dogs are considered more masculine. The Pythagoreans connected masculinity to odd numbers and femininity to even numbers (Lloyd 1984). In all these cases, the attribution of gender tells us more about how human minds work—about our tendency to organize what we see according to gender—than about any properties inherent in pants, shapes, cats or numbers, or about any of the constraints put on men and women in American (or Pythagorean) society. There is general agreement within a particular culture, at a particular time, in a particular context, about which objects, activities, personality attributes, skills, etc. are perceived to be masculine, which are understood as being feminine, and which are more or less ungendered. As the functioning of gender categories varies historically and cross-culturally, I need to clarify here that when I talk about “our” conceptions of gender I will be referring, with all due apologies to non-Western readers, to dominant conceptions held in the modern Western and English-speaking world. When I refer to “masculine” or “feminine” traits, I do not mean traits that are essentially “more appropriate for” or “more likely found in” persons of one sex or the other, but rather traits that have been culturally, metaphorically gendered.2

The dominant conception of gender is as a hierarchical dualism. That is, to the metaphorical connections outlined by Lakoff and Johnson of up-in-center-control-rational we can add “superior” and “masculine,” and to the connections of down-out-periphery-submission-emotional we can add “inferior” and “feminine.” The traditional, dominant conception of gender can be represented by the following picture:

That is, masculinity and femininity are construed of largely as opposites, with masculinity claiming the high status side of the line. Discussions about the metaphorical connection of this duality with numerous other hierarchical dualisms such as science/nature, mind/body, etc. are endemic in feminist scholarship (e.g., Hartsock 1983:241; Harding 1986:23). Tables like the following appear with great frequency, illustrating the metaphorical association of particular traits with gender in post-Enlightenment Western, white, thought:

The tendency to connect metaphorically behaviors, activities, and attributes with masculinity or femininity extends not only to cultural conceptions of appropriate social roles for women and men, but also far beyond, as in the cat and dog example. To a reader who would question the asymmetry of what I argue is the dominant conception of gender (who would, perhaps, prefer to think of the actual social meaning of gender differences in terms of a more benign complementarity) I need only point out some obvious manifestations of asymmetry in the social domain. Rough “tomboy” girls are socially acceptable and even praised, but woe to the gentle boy who is labeled a “sissy.” A woman may wear pants but a man may not wear a skirt. Even fathers who consider themselves feminist may feel much more comfortable taking their daughter to soccer practice, than they would taking their son to ballet. The hierarchical nature of the dualism—the systematic devaluation of females and whatever is metaphorically understood as “feminine”—is what I identify as sexism. Seen in this way, sexism is a cultural and even a cognitive habit, not just an isolated personal trait.

One way of changing the understanding of gender and value might be to assert simply that “feminine is good, too.” While one might be able to gain some ground by this route, when looking at the roles played by stereotypically feminine concepts and traits, it sooner or later becomes clear that some of these factors are quite unattractive. If masculine is “strong” and feminine is ”weak,“ who wants to be weak? Another way of challenging the association of masculinity with superiority and femininity with inferiority might be to decide to do away with gender associations entirely. Perhaps we can just talk about good and bad traits, and leave gender out of the discussion. While some may hope for such a case as an ultimate goal, it seems premature to throw away gender categories if they still are actively used as cognitive and social organizers. The line between overcoming gender distinctions and simply suppressing (or, the more psychoanalytic might say, repressing) them is, as will be discussed in Chapter 10, one that can be too easily crossed. I suggest a third alternative, based on a more specific diagnosis of what is wrong with the old hierarchical gender dualism.

THE OLD METAPHOR COLLAPSES CATEGORIES

In contrast to traditional dualistic conceptions, I suggest that opposition is itself only unidimensional in its basis of physical orientation, and not in the realms to which the dualism has been metaphorically applied. For example, “down” is clearly the opposite, negation, or reverse of “up,” but “emotional” is not unambiguously an antonym for “rational.” One might consider “irrational” to be a better antonym. If we think one-dimensionally and assert that each concept can have only one opposite, then the only way out of this dilemma is to collapse the rational/ emotional and rational/ irrational comparisons by equating emotion with irrationality (and rationality with lack of emotion). But we do not need to be limited to thinking onedimensionally. “Irrational” is the opposite of “rational” in that it signifies as lack of the latter; “emotional” might be construed as the opposite of “rational” in the sense of complementarity, i.e., that there is some value to achieving a balance including both capacities. My Webster’s dictionary (New Collegiate 1974) allows “complementary” as one definition of “opposite.” Dare we use it ourselves in our thinking about gender?

I would like to suggest that we think about “opposition” as encompassing relationships both of lack and of complementarity. I will use the word “difference” to include both these aspects of opposition plus a third concept that I will call “perversion.” A concept is a perversion of another if it is similar (not opposite) but different due to distortion, corruption, or degradation. For example, emotionalism, or the tendency to make judgments on purely emotional terms (and hence irrationally), is a perverse use of emotional capacity, just as rationalism, in which all emotion is suppressed, is a perverse use of rationality.

The three different concepts of difference—lack, perversion, and complementarity—can be illustrated with reference to conceptions of masculinity and femininity in Aristotle’s biology of sexual difference. In thinking about gender in terms of lack, masculinity is defined by certain attributes, and femininity by their absence. For example, from Aristotle: “The woman is as it were an impotent male, for it is through a certain incapacity that the female is female” (quoted in Lange 1983:9). Women, according to Aristotle, have less “heat” than men and, accordingly, less soul. This corresponds to a metaphor of “more is up; less is down.” A second form of difference is for the negative end to be a perversion of the positive end. Again, from Aristotle: “Whatever does not resemble its parents is already in a way a monster, for in these cases nature has… deviated from the generic type. The first beginning of this deviation is when a female is produced” (quoted in C.Keller 1986:47). The female, though having something in common with the male in origin, is considered to be “deviated,” deformed, or distorted. This corresponds to a metaphor of “health is up; sickness is down” or “virtue is up; depravity is down.” A third way is for opposites to be conceived of as complements. In the hierarchical dualism, the complementary is always asymmetric: socially constructed femininity or biological femaleness is seen as something of a necessary evil. Aristotle, again: “While the body is from the female, it is the soul that is from the male, for the soul is the reality [substance] of a particular body” (quoted in C.Keller 1986:49). Both are apparently necessary for procreation, though maleness has the role deemed more important. On a metaphorical level, while “up” is quite literally the reverse of “down,” the two belong to the same dimension; without experience of one we can have no conception of the other. Complementarity is, as mentioned, part of the dictionary definition of “opposition.”

Feminists would obviously not want simply to reaffirm Aristotle’s explanation of the differences between men and women. But the idea of multidimensionality may be helpful. The idea that opposition is not itself unidimensional matters because a richer understanding of multidimensional “difference” can free us from the straitjacket of hierarchical, unidimensional thinking about gender. Experience suggests that metaphors are not immutable; in fact the phenomenon of discovery in science (as well as the power of certain kinds of poetry) has sometimes been attributed to the creation of a new metaphorical association (Ortony 1979). Lakoff and Johnson suggest that “new metaphors have the power to create a new reality” (1980:45).

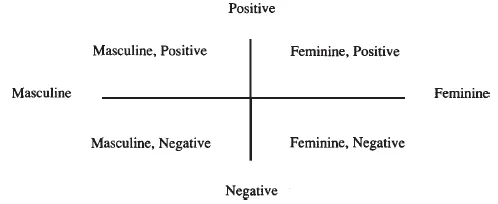

A NEW METAPHOR: THE GENDER-VALUE COMPASS

My new metaphor retains gender as a cognitive patterning system; it retains hierarchy in matters of value judgment; it retains opposition. I would argue that these are fundamental categories of thought that must be transformed rather than repressed.3 What this conception of gender gains over the unidimensional dualism is a radical break of gender categories from value categories, and an explicit exposition of the various meanings of difference. It can be presented in the form of a diagram which may seem deceptively simple: it just separates the masculinepositive and feminine-negative ends of the dominant conception into two separate dimensions: feminine/masculine and positive/ negative. I hope that this simplicity will make it immediately useful as a cognitive organizer. The apparent simplicity is deceptive because the jump from one to two dimensions doubles the number of categories involved— increases them from two to four—while tripling the types of relationships that can be represented: from that of poles on one dimension to relationships that are horizontal (which will represent complementarity), vertical (which will represent perversion), and diagonal (which will represent lack). This complexity makes the picture richer than it may first appear.

I will present the mechanics of the diagram first and then illustrate with examples of how it may clarify thinking. Imagine a situation or question that asks for a judgment about human behavior and that has often been answered in gender-oriented ways. Draw the diagram in two dimensions:

The shape of this diagram should have immediate cognitive “availability” for readers familiar with four-quadrant graphs or two-by-two matrices, without need for further metaphorical elaboration. For those readers who find this diagram unfriendly, I suggest thinking about it as analogous to a directional compass, with poles corresponding to north, south, east, and west. This interpretation suggests further metaphorical insights. As a compass, its service is to guide and direct—in this case to guide our thinking. It also “encompasses” a larger space than the old dualistic metaphor, which could be represented by the masculine-...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Acknowledgments

- Introduction

- Part I: Theory, Feminist and Economic

- Part II: Applications

- Part III: Specific Defenses

- Epilogue

- Bibliography