![]()

1

History of antifungals

EMILY L. LARKIN, ALI ABDUL LATTIF ALI, AND KIM SWINDELL

Introduction

Early treatments

Antifungals for the treatment of invasive infections

Polyenes

Nystatin

Amphotericin B

Azole antifungals

Early azoles

Second generation azoles

Third generation azoles

Echinocandin antifungals

New antifungals underdevelopment

Topical antifungals

Future agents

References

INTRODUCTION

Over the past decades, the incidence and diversity of fungal infections has grown in association with an increasing number of immunocompromised patients. The human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) epidemic, technological improvements in the fields of solid organ transplantation medicine, stem cell transplantation, neonatology, coupled with the advent of new immunosuppressive drugs have collectively attributed to an increase in the incidence of systemic fungal infections, including those caused by Candida, Aspergillus, Cryptococcus, Coccidioides, Pneumocystis, and Zygomycetes species. More recently, other species have begun to rival Candida albicans as major causative agents of fungal disease. For example, fluconazole-resistant non-albicans Candida species, such as C. glabrata, are now more prevalent in some hospitals [1,2]. Likewise, molds, such as Scedosporium, Fusarium, Rhizopus, and Mucor species, are now increasingly responsible for superficial and systemic mycoses in humans [3,4].

Healthcare professionals must carefully consider the expanded role of medically important fungi in order to provide optimal treatment of fungal infections in immunocompromised patient populations. Coincidently, novel therapies that target host defenses, fungal biofilm physiology, and emerging resistances must be developed in order to keep pace with changes in the etiology and the resistance patterns of fungal pathogens.

EARLY TREATMENTS

Antifungal therapies evolved slowly during the early years of the past century. For example, from the beginning of the twentieth century until after World War II, potassium iodide was the standard treatment for cutaneous fungal infections, including actinomycosis, blastomycosis, sporotrichosis, and tinea [5]. First derived from sea algae, potassium iodide was considered to exert a direct antifungal effect, although the complete mechanism of action remains unclear [6,7,8]. Contemporarily, radiation was used to treat severe tinea capitis infections, often with significant complications, including skin cancer and brain tumors [9].

In the 1940s, Mayer et al. [10] demonstrated that sulfonamide drugs, such as sulfadiazine, exhibited both fungistatic and fungicidal activities against Histoplasma capsulatum [11]. This discovery led to the formation and the use of sulfonamide derivatives for the treatment of blastomycosis, nocardiosis, and cryptococcosis [12,13,14].

Griseofulvin, a compound derived from Penicillium griseofulvum, has been widely used to treat superficial fungal infections since its isolation in 1939 [15]. In 1958, Gentles [16] reported the successful treatment of ringworm in guinea pigs using oral griseofulvin.

These successful attempts to develop novel and effective antifungal drugs encouraged the further study and discovery of new agents.

ANTIFUNGALS FOR THE TREATMENT OF INVASIVE INFECTIONS

Polyenes

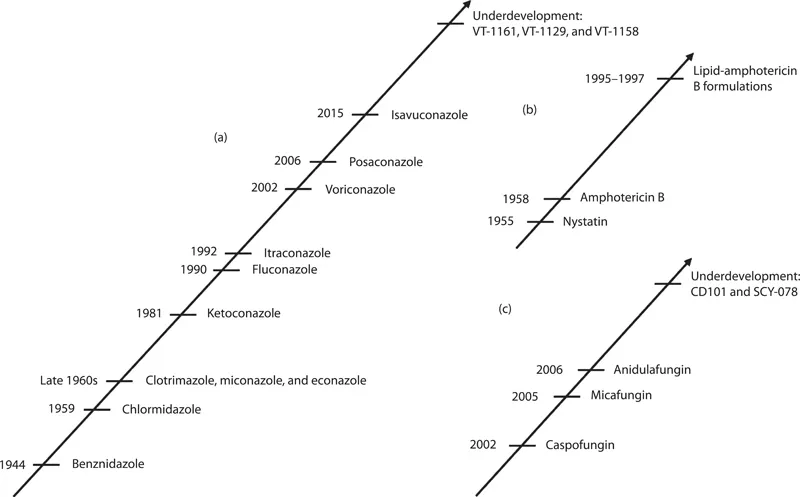

In 1946, polyene antifungals (Figure 1.1), which are effective against organisms with sterol-containing cell membranes (e.g., yeast, algae, and protozoa), were developed from the fermentation of Streptomyces [17,18]. These drugs disrupt the fungal cell membrane by binding to ergosterol, the main cell fungal membrane sterol moiety. As a result, holes form in the membrane allowing leakage of essential cytoplasmic materials, such as potassium, leading to cell death. From the 1950s until the advent of effective azole compounds in the 1960s, polyene antifungal agents were standard therapy for systemic fungal infections [19].

NYSTATIN

In 1949, while conducting research at the Division of Laboratories and Research of the New York State Department of Health, Elizabeth Lee Hazen and Rachel Fuller Brown discovered nystatin, a polyene derived from Streptomyces noursei [20,21,22]. In 1955, Sloane [23] reported topical nystatin to be particularly effective for treatment of noninvasive moniliasis (candidiasis), a frequent complication observed in children enrolled in early chemotherapeutic leukemia trials underway during this period [24]. Nystatin exhibited good activity against Candida and modest activity against Aspergillus species.

In aqueous solutions, nystatin forms aggregates that are toxic to mammalian cells both in vitro and in vivo. The insolubility and toxicity precluded its use as an intravenous therapy for systemic mycoses.

Subsequently, (NyotranOR), a more soluble liposomal nystatin formulation with reduced toxicity was developed [25]. The liposomal formulation consists of a freeze-dried, solid dispersion of nystatin mixed with a dispersing agent, such as a poloxamer or polysorbate [26,27]. The dispersing agent prevents aggregate formation in solution, increasing the drug’s solubility and decreasing toxicity while maintaining efficacy [27,28]. Liposomal nystatin has good activity in vitro against a variety of Candida species, including some amphotericin B–resistant isolates [28].

Studies by Oakley et al. [29] showed that NyotranOR was more effective than liposomal amphotericin against Aspergillus species. Although the liposomal form of nystatin was less toxic than conventional nystatin, unacceptable infusion-related toxicity unfortunately caused a halt in the development of this drug [30,31,32].

AMPHOTERICIN B

Amphotericin B is a fungicidal polyene antibiotic and, like other members of the polyene class, is effective against organisms with sterol-containing cell membranes [19]. Amphotericin B was extracted from Streptomyces nodosus, a filamentous bacterium, at the Squibb Institute for Medical Research in 1955 and subsequently served as the standard treatment for many invasive fungal infections [33].

Figure 1.1 Historical development of the antifungal agents, including novel antifungals: (a) azoles, (b) polyenes, and (c) echinocandins (1,3-β-glucan synthase inhibitors).

Amphotericin B provided activity against invasive Aspergillus superior to that of previously available antifungal agents [33,34]. Amphotericin B continues to be effective for the treatment of fluconazole-resistant fungal infections [19,30]. Like other polyenes, amphotericin B exhibits dose-dependent toxicities including renal impairment and hypokalemia [19,30,34,35]. Renal toxicity associated with polyene antibiotics is believed to be mediated by the drug interaction with cholesterol within the mammalian cell membrane, resulting in pore formation, abnormal electrolyte flux, decrease in adenosine triphosphate (ATP), and eventually a loss of cell viability [19].

In the early 1980s, several research groups developed a new liposomal amphotericin B formulation. Graybill et al. [36] published the first extensive study investigating the treatment of murine cryptococcosis with liposome-associated amphotericin B. The tissues of Crytococcus-infected mice treated with the liposome-associated formulation were demonstrated to have lower tissue fungal burden than the tissues of similarly-infected mice treated with conventional amphotericin B. Liposome-associated amphotericin B demonstrated increased efficacy attributed to the ability to treat with higher doses (due to its lesser toxicity) than was possible with amphotericin B deoxycholate (conventional amphotericin B formulation) [36,37].

In the past decades, three novel liposomal formulations of amphotericin B have been approved for use in the United ...