The School Handbook for Dual and Multiple Exceptionality

High Learning Potential with Special Educational Needs or Disabilities

- 100 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

The School Handbook for Dual and Multiple Exceptionality

High Learning Potential with Special Educational Needs or Disabilities

About this book

The School Handbook for Dual and Multiple Exceptionality (DME) offers a range of practical strategies to support SENCOs, GATCOs, school leaders and governors in developing effective provision for children that have both High Learning Potential and Special Educational Needs or Disabilities. Building on the principles of child-centred provision and coproduction, it provides useful tips on developing the school workforce to better identify and meet the needs of learners with DME.

Relevant for learners in primary, secondary or specialist settings, the book focuses on ways of meeting individual needs and maximising personal and academic outcomes. It includes:

- An explanation of what DME is and why we should care about it

- Practical advice and guidance for SENCOs, GATCOs and school leaders on developing the school workforce

- A discussion of the strategic role of governors and trustees in the context of DME

- Suggested approaches to ensure effective coproduction between families and professionals

- Case studies exploring the experiences of learners with DME

- Sources of ongoing support and resources from professional organisations and key influencers.

This book will be beneficial to all those teachers, school leaders, SENCOs, GATCOs, governors and trustees looking to support learners by identifying and understanding DME. It recognises the central role that leaders and governors play in setting the inclusive ethos of a school and suggests ways for schools to ensure that all learners have the opportunity to meet their full potential.

Frequently asked questions

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Information

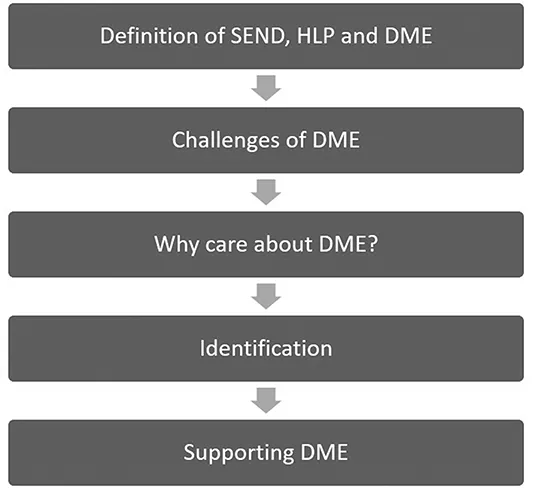

1 What is DME and why should we care?

Definition of SEND

- significantly greater difficulty in learning than the majority of others of the same age; or

- a disability which prevents or hinders them from making use of educational facilities of a kind generally provided for others of the same age in mainstream schools or mainstream post-16 institutions.

- Communication and interaction – children and young people with speech, language or communication issues. Specific learning difficulties such as dyslexia or a physical or sensory impairment such as hearing loss may also lead to communication difficulties. Children and young people with an Autism Spectrum Condition may have difficulties with communication, social interaction and imagination. In addition, they may be easily distracted or upset by certain stimuli, have problems with change to familiar routines or have difficulties with their co-ordination and fine-motor functions.

- Cognition and learning – children and young people with learning difficulties may learn at a slower pace than other children and may have greater difficulty than their peers in acquiring basic literacy or numeracy skills or in understanding concepts, even with appropriate differentiation, including dyslexia, dyscalculia and dyspraxia. However, those with cognition and learning issues may also have other difficulties such as speech and language delay, low self-esteem, low levels of concentration and under-developed social skills.This definition of cognition and learning issues can be difficult to demonstrate for children and young people with DME, many of whom are learning at age-appropriate levels and pace. The key is not to evaluate their learning difficulty in relation to that of their class peers but in relation to what and how they are capable of otherwise learning with the right support. The risk is that children and young people with DME can appear to be operating at or above average within their peer group. As shall be seen later, particularly in some of the case studies, whilst this can be difficult to measure, it is not impossible to identify and provide for.In circumstances where DME is unidentified, children are at risk of developing additional Special Educational Needs, particularly social, emotional and mental health issues. They may then need additional support in these areas, even where it did not present as a Special Educational Need in the first instance but arose from inaccurate identification within the broad area of cognition and learning.

- Social, emotional and mental health – children and young people who have difficulties with their social and emotional development may have immature social skills and find it difficult to make and keep healthy relationships. Resulting issues can range from being withdrawn or socially isolated to having disruptive or challenging behaviour. This can lead to emotional health issues such as self-harm, eating disorders, trichotillomania, anxiety or depression. Some children and young people may also have other recognised disorders such as attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), attachment disorder, anxiety disorder or, more rarely, conditions such as schizophrenia or bipolar disorder.

- Sensory and/or physical – children or young people with vision impairment (VI), hearing impairment (HI) or multisensory impairment (MSI) or other physical difficulties would fall into this broad area.

Definition of HLP

- More able, Most Able or High Attainers – these are the current terms used by Ofsted and the Department of Education and focus on ‘those who have abilities in one or more academic subjects such as mathematics or English’.

- More/Most Able – this term either on its own or with gifted and talented was inserted by schools and government and reflects the unease which many people felt at the term ‘gifted and talented’ which was seen as ‘elitist’ and ‘not reflecting the education situation in many schools’. More/most able (which are often used interchangeably) was defined as those who have abilities in one or more subject areas and the capacity for or ability to demonstrate high levels of performance. Thus, someone could be academic because they worked hard and applied themselves rather than because they had an innate ability in one or more subjects.

- More Able and Talented – this was used by the Welsh Government to show pu...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Endorsements

- Half Title

- Series Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Table of Contents

- Foreword: Danielle Brown MBE

- Introduction

- 1. What is DME and why should we care?

- 2. Equipping the school workforce

- 3. Leadership and governance

- 4. Effective relationships with learners and their families

- 5. DME provision Real stories

- Conclusion: The way forward for DME in your school

- References

- Appendix 1: Glossary of terms used

- Appendix 2: DME support available for schools

- Appendix 3: Ten myths of supporting pupils with DME

- Index