- 304 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Absorbable and Biodegradable Polymers

About this book

Interest in biodegradable and absorbable polymers is growing rapidly in large part because of their biomedical implant and drug delivery applications. This text illustrates creative approaches to custom designing unique, fiber-forming materials for equally unique applications. It includes an example of the development and application of a new absor

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

Section D: Growing and Newly Sought Applications

11: Tissue Engineering Systems

Chuck B. Thomas and Karen J.L. Burg

11.1 Historical

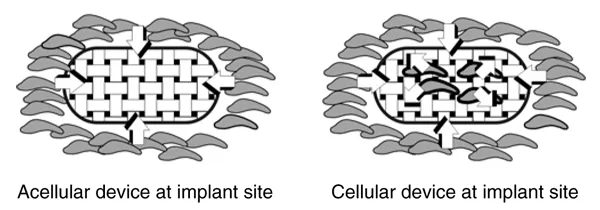

Tissue engineering is generally defined as the development of biologically based replacement tissues and organs. This is a broad definition and may incorporate cellular or acellular devices. In the case of acellular tissue engineering devices, the implant will promote growth of the existing tissue (Figure 11.1). The cellular device will supply new cells to the implant site that will either augment the existing cell population or reintroduce a missing population (Figure 11.1). Additionally, the cellular device may or may not incorporate a materials element. In many cases, however, an absorbable polymeric substrate (otherwise termed as a “matrix” or “scaffold”) is a key component and is sculpted to provide the appropriate form for the cellular component. The substrate may be used as a temporary delivery vehicle on which cells are housed; following implantation, the substrate absorbs at a defined rate as the tissue acquires the initial shape.

FIGURE 11.1 Acellular mesh induces tissue ingrowth (left) while cellular mesh integrates with surrounding tissue (right).

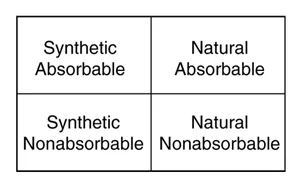

FIGURE 11.2 Four classifications of polymeric biomaterials.

Although the term “tissue engineering” was coined years earlier in a clinical explant study of a polymethylmethacrylate (PMMA) keratoprosthesis, 1 Langer and Vacanti brought the terminology into the public eye with their review of the field in 1993.2 Langer and Vacanti detailed how the field of tissue engineering could be used to provide clinical solutions for the replacement of ectodermal, endodermal, and mesodermal-derived tissue. At least 26 times they noted the importance of polymers in tissue engineering research, ranging from the treatment of Parkinson’s disease and the regeneration of peripheral nerves to the design of vascular grafts and the regeneration of cartilage. Two properties are typically used to classify the tissue engineering polymers. First, the material is categorized by its affinity to break down in vivo; that is, it is termed either absorbable or nonabsorbable. Second, the source of the material is used to classify the material as natural or synthetic. All four combinations of these characteristics (Figure 11.2) have found use in tissue engineering.

11.1.1 Synthetic Polymers

Polylactides have been researched for over 30 years in applications such as rods and films for bone fixation and sutures.3 Polyesters such as polyglycolide (PGA) and poly-L-lactide-co-glycolide (PLGA) have been used since the 1970s as biodegradable sutures.4–8 Polydioxanone, a polyetherester, has been utilized as a biodegradable suture since the early 1980s.9,10 Polyorthoesters have been evaluated for drug delivery applications due to their surface erosion characteristics; they have complex degradation products, and they require additives to promote erosion.11,12 Polyanhydrides have also been researched for drug delivery. Langer conducted studies on polycarboxybisphenoxypropane (PCPP) and found that by incorporating sebacic acid (SA) with PCPP, the degradation rate could be improved.12

Since the 1960s, hydrogels have been employed in biomedical applications such as wound dressings and thus were incorporated immediately into tissue engineering research.13 One of the earliest hydrogels studied, Hydron™ (Hydro Med Sciences, Cranbury, NJ), consisted of a composite system of polyhydroxyethylmethacrylate (PHEMA) and polyethylene glycol (PEG).14 It was studied for various applications including wound dressings; however, results from different studies of this material were conflicting.15 While it was lauded for alleviating patient pain and being easily applied, reports were also published that indicated Hydron had difficulty in adhering to the wound, cracking in many instances, and requiring removal from the wound.16–18 Vigilon® (C. R. Bard, Inc., Covington, GA), a wound dressing hydrogel, was developed in the 1980s.19 Vigilon consisted of 96% water and polyethylene oxide (PEO) placed between two polyethylene films, and it was found to be impermeable to bacteria and permeable to oxygen. Vigilon also was able to absorb exudate from the tissue without adhering to it, and the hydrogel was practically translucent.20,.21

11.1.2 Natural Polymers

The first polymers used as tissue engineering scaffold materials were natural polymers. In the late 1970s and early 1980s, Bell and co-workers researched collagen-based polymers in what are now considered tissue engineering applications.22,23 These studies included the development of full thickness skin-equivalent grafts that consisted of a rat collagen lattice initially cast with rat fibroblasts. After an in vitro growth phase, the subsequent dermal layer was seeded with epidermal cells from the same host animal, and the entire construct was implanted into an open skin wound on the back of the host. The grafts became vascularized, inhibited wound contraction, filled the original wound space, and, other than the absence of hair follicles and sebaceous glands, resembled normal skin. Yannas and co-workers performed studies in the 1970s and 1980s with porous crosslinked copolymers of collagen and glycosaminoglycans for the purpose of designing artificial skin.24,25 Yannas also developed copolymers of collagen and proteoglycans for skin and peripheral nerve repair.26

Alginate, a natural polysaccharide, is obtained from seaweed and finds widespread use in tissue engineering research. Alginate is comprised of chains of guluronic acid and mannuronic acid, with the amount and length of the guluronic blocks having a direct impact on its physical and mechanical properties. When alginate is combined with a source of divalent cations such as Ca++ or Mg++, it forms a gel. Early research with alginate gels in the 1980s focused on their potential use as microencapsulation vehicles for cells.27 Although alginate has good biocompatibility, it cannot be broken down enzymatically in the human body. Another drawback of alginate is that, depending on the seaweed source, the relative amounts and ratio of guluronic acid and mannuronic acid vary considerably.

11.2 Evolution and Status

11.2.1 Nonabsorbable and Absorbable Polymers

Focus has changed with time from nonabsorbable to absorbable polymers. Absorbable polymers typically take the form of fibrous meshes, porous scaffolds, or hydrogels. If the polymer can degrade at a controlled rate, the body’s own cells can infiltrate the matrix and replace the polymer space with natural tissue. The use of an absorbable polymer can have many advantages, such as the following:

- Absorbable polymers provide less risk of permanent infection than nonabsorbable polymers.28

- Absorbable polymers can be optimized for specific applications. For example, they can be manufactured to provide a local acidic or basic environment for the cells. Their porosity and pore size can be tailored to alter mechanical properties and to provide optimal growth parameters for specific cell types. In addition, their degradation can be altered so that the polymer erodes from the inside (bulk erosion) or by surface erosion. Side chains can also be included in the polymer design so that drugs, growth factors, hormones, and nutrients can be released during degradation.29

- Absorbable implants do not necessitate a removal operation, which is advantageous to both the patients and the economy.30

11.2.2 Synthetic and Natural Polymers

Selection of a tissue engineering substrate includes a choice between absorbable and nonabsorbable material, as well as a choice between synthetic and naturally derived materials. The most common synthetic polymers used for fibrous meshes and porous scaffolds include polyesters such as polylactide and polyglycolide and their copolymers, polycaprolactone, and polyethylene glycol. Synthetic polymers have advantages over natural polymers in select instances, suc...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Preface

- Acknowledgment

- The Editors

- Contributors

- Section A: Introduction Notes

- Section B: Development and Application of New Systems

- Section C: Developments in Preparative, Processing, and Evaluation Methods

- Section D: Growing and Newly Sought Applications

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Absorbable and Biodegradable Polymers by Shalaby W. Shalaby,Karen J.L. Burg in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Medicine & Biomedical Science. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.