- 232 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

Unemployment is the most serious economic and social problem in Europe today. Although the extent varies from region to region, it is generally most extreme in large cities. This volume asks why European unemployment is so high and examines the policies adopted at local, national and European level to tackle the problems. It also includes five case

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Unemployment in Europe by Valerie Symes in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Negocios y empresa & Negocios en general. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

UNEMPLOYMENT IN THE EUROPEAN COMMUNITY

Unemployment in the European Union has risen more or less continuously in the past fifteen years and is ‘the single most serious challenge facing Member States today’ (CEC 1993). In 1994 registered unemployment stood at over 12 per cent, with sixteen million officially unemployed. The number of people seeking work is even higher as official statistics underestimate joblessness. Unemployment levels vary a great deal between Member States, with very much higher rates in certain regions and countries of the Community. The problems arising from unemployment are not only economic problems of inefficiency arising from wastage of human resources, rising public sector deficits and possible monetary instability arising from this, but also an increase in social tension and social costs in terms of ill health, increasing poverty, family and community breakdown, and arguably increasing crime levels.

This chapter will examine the causes of the rise in unemployment in Europe and look at the relative seriousness of the problem for different groups.

European economies are said to have special features that result in higher levels of unemployment than similar advanced industrialised economies. This is the question that will be addressed first of all, as the implication is that if the factors behind the higher unemployment level can be identified, action can follow to reduce the problem.

Unemployment in the period 1981–91 was higher for the European Community as a whole than in other major economies. Table 1.1 shows the unemployment rates (standardised) for the USA, Japan, the EC and selected countries within the EC which will be the focus of later study.

The USA and Japan had lower unemployment rates than the European Community in both 1981 and 1991. Individual countries within the EC show greater disparities in unemployment rates ranging in 1991 from 4.3 per cent in Germany to 16 per cent in Spain. Apart from Germany all other countries under study had higher rates than the USA and Japan in both years.

Figures for the individual countries demonstrate the wide disparities in the problem of unemployment throughout the Community. The amalgamation of West Germany with East Germany in 1989 has resulted in an increase in unemployment in Germany more recently, and special problems, which will be illustrated by the case study of Frankfurt. Apart from Germany all countries within the study have showed higher levels of unemployment than both of the other major economies shown in the table.

| 1981 | 1991 | |

| USA | 7.5 | 6.6 |

| Japan | 2.2 | 2.1 |

| EC | 9.9 | 8.8 |

| France | 7.4 | 9.4 |

| Germany | 4.2 | 4.3 |

| Netherlands | 8.5 | 7.0 |

| UK | 9.8 | 8.9 |

| Spain | 13.8 | 16.0 |

Source: OECD Quarterly Labour Force Statistics (1992)

One would expect that as national income rose employment would also rise as there is normally a strong link between growth and employment. In terms of national income growth the EC as a whole and the individual countries did not perform significantly worse than the USA and Japan for the period 1981–89 (see Table 1.2). The average growth rate in Japan was 4.2 per cent, nearly matched by the Netherlands with 4.1 per cent. The USA’s growth rate was surpassed by the Netherlands, Spain and the UK. Growth in employment, however, shows a different picture with employment growing at 2 per cent p.a. in the USA, 1.2 per cent p.a. in Japan, but with the exception of the UK at 1.2 per cent all other countries experienced employment growth of below 1 per cent p.a. This could be explained by changes in the labour force (Table 1.2, column 3). The labour force can reflect demographic changes such as the number of young people coming onto the labour market, or social changes such as more married women wishing to work, but the number of people offering themselves for work can also reflect the demand for labour. As working opportunities rise so do the number of people seeking employment. The reverse is also true that as employment opportunities fall the labour force can fall because people feel it is no longer worthwhile to seek employment. This can be particularly relevant where adequate welfare payments provide a real choice between seeking work and not seeking work. It is difficult, therefore, to interpret changes in the labour force in this context. What the figures show is that employment grew faster than the labour force in the USA and in the UK, at the same rate in France and Spain and at lower rates in the EC as a whole and in Germany, the Netherlands and Spain (Table 1.2).

| Real GDP/GNP | Employment | Labour force | |

| USA | 2.9 | 2.0 | 1.6 |

| Japan | 4.2 | 1.2 | 1.2 |

| EC | 2.5 | 0.6 | 0.7 |

| France | 2.2 | 0.3 | 0.3 |

| Germany | 2.5 | 0.1 | 0.6 |

| Netherlands | 4.1 | 0.4 | 0.6 |

| UK | 3.2 | 1.2 | 0.8 |

| Spain | 3.3 | 0.9 | 1.3 |

Source: OECD Employment Outlook (1992)

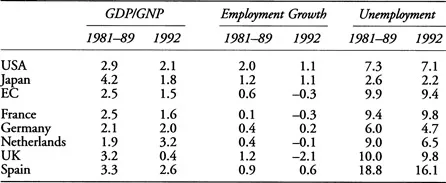

With the advent of the recession after 1991 the effects of the recession on employment growth were more marked in Europe than in the USA and Japan (Table 1.3).

Table 1.3 Changes in real GDP/GNP and employment growth, 1981–89 and 1992

Source: OECD Employment Outlook (1992)

Although in 1992 unemployment grew in the USA and Japan employment also grew by 1.1 per cent whereas in the EC it fell by an average of 0.3 per cent and the UK was worst hit by a fall in employment of 2.1 per cent. For more than a decade the rate of job creation has been lower and the rate of unemployment higher on average in the EC than in either the USA or Japan despite the fact that growth rates have not been significantly different.

Another feature of unemployment in which the European Community is in stark contrast to the USA is in the proportion of the unemployed who have been without a job for longer than a year, the long-term unemployed (Table 1.4).

| 1983 | 1987 | 1989 | 1990 | |

| USA | 13.3 | 14.0 | 7.4 | 5.7 |

| France | 42.2 | 45.5 | 43.9 | 38.3 |

| Germany | 39.3 | 48.2 | 49.0 | 46.3 |

| Netherlands | 50.5 | 46.2 | 49.9 | 48.4 |

| UK | 47.0 | 45.9 | 40.8 | 36.0 |

| Spain | 52.4 | 62.0 | 61.5 | 54.0 |

Sources: Eurostat; INSEE; Labour Force Survey; Ministry of Employment and Social Security, Spain; Bureau of Labour Statistics, USA

In 1983, of the unemployed in the USA only 13.3 per cent had been unemployed for more than a year. This had fallen to 5.7 per cent by 1990. In Europe the proportion of long-term unemployed was over three times that in the USA ranging from 39.3 per cent in Germany to 52.4 per cent in Spain. In Germany and Spain the proportions had increased to 46.3 per cent and 54 per cent by 1990. In the three other countries it had reduced but was seven and nine times the rate of the United States.

Many studies have addressed the questions ‘Why has European unemployment been persistently higher than that of the USA and Japan?’ and ‘Why has the number of long-term unemployment differed so much between the United States and European countries?’ The explanations for the former can be categorised into the effect of aggregate demand; the role of wages in turn affected by the unemployment compensation and institutional factors; and structural change. Long-term unemployment is again linked to the unemployment benefit system but also to hysteresis effects and discrimination.

Taking the first of these explanations, the role of aggregate demand, Bean, Layard and Nickell (1986), Blanchard and Summers (1986), Lawrence and Schultz (1987), Drèze and Bean (1990) all identify demand conditions in Europe as being important in creating and maintaining high levels of unemployment, especially in the EC. Tight monetary and fiscal contractions in the 1980s in most EC countries, with the exception of Mitterand’s expansionary programme in France in the early 1980s, and the interdependence of European economies with high levels of inter-Europe trade, made any expansionary strategy by individual economies impotent. It is argued that these aggregate demand shocks left a serious legacy in destroying investor confidence, and damaged the ability of the labour markets to function effectively. Underutilised capacity affected the demand for investment. The growth of demand is linked to both government expenditure and world trade. Governments were cutting back on expenditure and reducing public deficits. High interest rate policies to control inflation further reduced investment, and at the margin caused closures through rising business costs. European shares of world trade fell as a result of differences in the growth rates of domestic and foreign prices through the price elasticity of demand for imports and exports.

The sustained growth in unemployment in Europe since 1970 challenged the premise of a ‘natural’ or Non-Accelerating Inflation Rate of Unemployment (NAIRU) toward which an economy will gravitate. The idea is that an increase in unemployment will lower the rate of inflation since wage costs will lower as a result of unemployment, unemployment will then reduce as the demand for labour increases with falling real wages. It was found, however, that high rates of unemployment had little impact on inflation. In fact unemployment and inflation in EC countries often went up together. It was reported (Blanchard and Summers 1986) that the NAIRU rose from 2.4 per cent in 1967–79 to 9.2 per cent in 1981–83 in the UK; from 1.3 per cent to 6.2 per cent in Germany and from 2.2 per cent to 6.9 per cent in France in the same periods. Flanagan (1987) estimated a NAIRU for both France and Germany 1983–87 of 6.0 per cent and NAIRU increased more in most of Europe than in North America. Policy makers in this situation were unwilling to stimulate demand as it was thought that it would lead to higher inflation not higher output.

Control of inflation was the major preoccupation of macroeconomic policy in Europe in the 1980s in an attempt to generate export led growth through more competitive prices and reduced uncertainty on future prices. As previously mentioned any expansionary policy that would be effective in reducing unemployment would have to be a concerted effort by all major EC economies. Expansionary fiscal policy was also seen as capable of exerting only temporary effects as it would induce balance of trade and public deficits and lead therefore to a reversal of policy (Drèze and Bean 1990).

In high unemployment countries the reduction in wage share of value added was low when unemployment was high. Wage theory would suggest that high unemployment would cause a reduction in wages and that this would be reflected in the wage share. Table 1.5 shows average percentage change per annum in employee compensation in the USA, Japan and the EC.

The share of wages in national incom...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Full Title

- Copyright

- Dedication

- Contents

- List of figures

- List of tables

- Acknowledgements

- Introduction

- 1 UNEMPLOYMENT IN THE EUROPEAN COMMUNITY

- 2 URBAN UNEMPLOYMENT IN EUROPE

- 3 THE ROLE OF THE EUROPEAN COMMUNITY IN HELPING THE UNEMPLOYED

- 4 MONTPELLIER

- 5 MANCHESTER

- 6 ROTTERDAM

- 7 BARCELONA

- 8 FRANKFURT AM MAIN

- 9 UNEMPLOYMENT IN EUROPEAN CITIES: CAUSES AND POLICIES

- 10 PRESCRIPTIONS FOR THE FUTURE

- Notes

- Bibliography

- Index