Introduction

Omar Mir Seddique, also known as Omar Mateen, killed forty-nine people and wounded fifty-three others in a mass shooting at the Pulse gay nightclub in Orlando, Florida, on June 12, 2016. During calls with negotiators, Mateen pledged his allegiance to Abū Bakr al-Baghdadi, the leader of the radical Islamist terrorist group ISIS. Mateen was born in New Hyde Park, New York, had an associates degree in criminal justice technology, and worked for nine years as a security guard—on the surface, an unlikely terrorist. However, as the case study in Chapter 5 discusses, Mateen was unraveling through the years, culminating with his mass shooting at Pulse. In his calls with police negotiators, Mateen pledged his allegiance to ISIS and said the shooting was “triggered” by an airstrike six weeks earlier in Iraq that killed Abu Wahib, an ISIS commander (Orlando Sentinel 2016). Mateen’s target selection methodology came to light during the FBI’s questions of his wife; he was looking for a lightly protected venue, packed with unsuspecting people (CBS News 2018). After surveilling a Disney park and another nightclub, both with armed law enforcement at the entrance, he chose Pulse.

In the post-9/11 world, the United States made great strides to further reinforce already hardened targets such as military installations, government buildings, and transportation systems. Those facilities now employ concentric rings of security, more cameras, and a robust security workforce, serving to repel would-be terrorists and violent criminals. However, as these hard targets are further reinforced with new technology and tactics, soft civilian-centric targets such as the Pulse nightclub are of increasing interest to terrorists. But this concept is not new; although lost in the news at the time, evidence collected following the 9/11 attack proved the aircraft hijackers also accomplished preliminary planning against soft targets, surveying and sketching at least five sites, including Walt Disney World, Disneyland, the Mall of America, the Sears Tower, and unspecified sports facilities (Merzer, Savino, and Murphy 2001). Despite horrific terrorist operations against civilians, such as the 2002 Beslan school massacre, the 2005 Moscow theater siege, the 2008 Mumbai attacks, the 2013 Nairobi shopping mall assault, and the 2015 Paris attack, few resources are applied toward hardening similar soft targets in the United States. A very small portion of our national security budget and effort is spent protecting civilian venues. Responsibility for security is often passed on to owners and operators, who have no training and few resources. In military terms, we are leaving our flank exposed.

The problem is far more complex than a simple lack of funding; the challenges are also psychological and tactical. First of all, contemporary terrorism has no moral boundaries. Who could have predicted, even ten years ago, that schools, churches, and hospitals would be considered routine, legitimate targets for terrorist groups? Outrage and outcry at the beginning of this soft targeting era has given way to acceptance. Psychologically, it is more comfortable to pretend there is no threat here in the homeland, and these heinous attacks will always happen “somewhere else.” Americans also have a very short memory—a blessing when it comes to resiliency and bouncing back from events like devastating civil and world wars, the Great Depression, and 9/11. However, in terms of security, this short-term memory can be our Achilles heel when faced with a determined, patient enemy. In fact, we almost have a revisionist history, downplaying and explaining away previous attacks as individual acts of violence by groups of madmen, not seeing the larger trends.

Some facility owners and managers choose to roll the dice, sacrificing a robust security posture to provide a more pleasant experience for students, worshippers, shoppers, or sporting or recreational event fans. In a clear example of how we fail to learn from violent massacres and change, take the case of the Valentine’s Day massacre on 2018 at Marjory Stoneman Douglas High School in Parkland, Florida. The building had the exact same doors that doomed Sandy Hook six years earlier—locking from the outside with a key, and glass window panes in the doors to allow the attacker to see students and shoot inside the room. We are a change-resistant culture fighting several emotional traps that, frankly, keep getting innocent people killed.

We must remember the choice of target for terrorists is not random, particularly for radical religious groups seeking elevated body counts, press coverage, and a fearful populace in order to further their goals. Hardened targets repel bad actors, and, as the case studies in this book illustrate, unprotected soft targets invite.

Attacks against soft targets have a powerful effect on the psyche of the populace. Modern terrorist groups and actors redrew the battlefield lines, and places where civilians once felt secure were pulled into the war zone. Persistent, lethal attacks by al-Qaeda-affiliated terrorists against churches, hospitals, and schools in the Middle East and Africa have even successfully shifted the center of gravity in major conflicts. When places formerly considered “safe” become targets, frightened civilians lose the will to fight. They may flee and surrender the territory to the aggressor or be compelled to assist their efforts. Alternatively, as seen with Boko Haram in Nigeria, the suffering population may rise up en masse, compelling the government to militarily engage or make concessions to insurgents to stop the brutality against noncombatants.

Due to our country’s adherence to the Geneva Conventions, we will not attack soft targets with no military necessity, even if the enemy takes shelter among citizens. In our eyes, civilians are not treated as combatants and therefore are not targets. Injured civilians are protected, not fired upon. Places of worship are never purposely hit. Schoolyards filled with children are not a target. We are intellectually unwilling to imagine an enemy who does not share what we believe to be universally accepted moral codes; therefore, have a severe blind spot and are wholly unprepared to protect soft targets in our country.

Our enemies see a busload of children and a church full of people as legitimate targets. Terrorists do not care about “collateral damage,” a phrase Timothy McVeigh unremorsefully used to describe the daycare children killed in his attack at the Alfred Murrah building. We also tend to forget domestic terrorists, our fellow citizens, routinely attack soft targets in our country, from arson to shootings and bombings. Hate groups and crimes are also on the rise; no matter your gender, race, religion, or sexual preference, there is a group in the United States actively or passively targeting you. Therefore, in light of this complex threat from a variety of bad actors, we must prepare both psychologically and tactically to harden our soft targets and lessen their vulnerability.

Protecting soft targets presents unique challenges for law enforcement since the buildings are usually privately owned and responsibility rests on the owners to secure the property and its occupants. Therefore, collaboration is critical: educating the owners on the threat, assisting with vulnerability assessments, and helping to harden the venue or establishment. However, when I speak with college presidents, high school principals, clergy, or owners of soft target venues about the possibility of a terrorist attack on their property, they may convey a feeling of hopelessness (there is not much we can do to prevent or mitigate the threat), infallibility (it will never happen here), or inescapability (it is destiny or unavoidable, so why even try). Those who frequent soft target facilities—employees and patrons alike—typically believe “It can’t happen to me.” They have a sense of invulnerability. Even worse, others may believe “If it is going to happen, there is nothing I can do about it anyway,” expressing inevitability. People with these mindsets are a detriment not only in security efforts before an attack but also in emergency situations, with no awareness of the threat, mental preparation, or sense of determination to engage during the situation. In an emergency, those without a plan or resolve may wait for first responders and law enforcement to arrive and rescue them before taking steps to save their lives and those of others. The Sandy Hook shooting event was over in six minutes, with twenty-six dead: there is no time to wait for help when the attacker is determined and brings heavy firepower to the fight. You are the first responder.

Most experts agree that, with our newly robust intelligence capabilities, another coordinated mass casualty event in multiple locations on the scale of the 9/11 attacks is unlikely. However, a Paris or Mumbai-styled event in a city with multiple avenues of approach, or a mass casualty bombing at a soft target location is more probable, and will still have an associated shock factor.

There is a general hesitation for the government to share specific threat information with the public, and perhaps officials do not want to cause panic; however, education is the best way to lower fear, as people will feel they can protect themselves and their loved ones. As witnessed in several natural disaster events in our country since 9/11, citizens are overly reliant on the government, lacking supplies at home as simple as flashlights, radios, batteries, nonperishable food, and water. Unfortunately, many police departments and hospitals took large funding cuts due to our country’s budgetary crisis and have been slow to rebound. Meaning response time may be slower than anticipated. During mass casualty events such as shootings or a fire, victims routinely are unable to locate emergency exits and they have no plan to defend themselves and others. Furthermore, most people do not understand what it means to “shelter in place” or how to follow other orders given during a serious emergency. The combination of lack of education about the threat, a feeling of invulnerability regarding soft target attacks, over-reliance on the government for help, and lack of first-response resources is potentially disastrous. We must educate citizens on the threat and response, so they become valuable force multipliers, instead of adding to challenges at the scene.

Security training and resources are typically the first to go during budget-cutting drills. When faced with a budgeting dilemma, leaders should ask: “What is the cost for not protecting our people?” Certainly, most schools, churches, and hospitals are not flush with cash and find it difficult to spend valuable dollars on security. Often, they make arbitrary decisions instead of using a system to assess vulnerability and threat, and then obtain the right mitigation tools to lower risk and protect their unique venue. With regard to profit-making soft targets such as malls and sporting and recreational venues, there is a desire for balance between security and convenience, minimizing impact to the customer. Business owners see customer backlash when other facilities like airports add layers of active, hands-on security and it likely discourages them from pursuing similar activities. For example, the addition of backscatter technology at airports drew the ire and scrutiny of millions of people, many of whom did not even fly on a regular basis. Even news of the almost-catastrophes in flight with shoe and underwear bombs did little to persuade the public for the necessity for these systems. Security may not be popular, and security decisions should not be made by consent.

If businesses are concerned about their reputation for long security lines and visitor frustration, owners should consider the damage to their reputation should a mass casualty terrorist or violent criminal attack happen on their property. For instance, the movie industry as a whole was impacted by the shootings at the Cinemark Theater in Aurora, Colorado, on July 20, 2012, at the premiere of the movie The Dark Knight Rises. In response to the violent attack, the film’s producer, Warner Brothers Studios, pulled the movie and all of its violent movies from theaters. As attendance dropped dramatically worldwide in light of the shooting, theater owners paid extra for increased security to reassure their customers. Cinemark not only paid the burial expenses of the twelve victims but also gave each family $220,000 and covered their legal bills. The company avoided paying millions of dollars of hospital bills for the seventy injured theatergoers, as they were forgiven and funded by the state. However, despite these actions, Cinemark was still sued by the families for not preventing the event, with some decisions still pending.

Another example—the lavish Westgate Mall, portrayed as a symbol of Kenya’s future and costing hundreds of millions of dollars to build, had high-end stores and affluent customers who generated millions of dollars in revenue weekly. The mall was completely destroyed in the four-day siege with al-Shabaab terrorists, and only half of the store owners had terrorism insurance (Vogt 2014). Stores were looted during and after the event by corrupt soldiers, adding to the financial ruin of shop owners. Rebuilding the mall was necessary to show resilience and national pride; however, the cost, approximately $17 million, was exorbitant for the country and insurers. Also, the inability of mall personnel to detect the planning stages of the attack, the ineffective response by armed mall security to put down the offensive, and the lack of communication with shoppers and store owners inside the mall about the unfolding events were widely criticized. The downplaying of the severity of the situation by the government and its sluggish, uncoordinated response cast doubt on its ability to handle violent events in the country. The tourism industry, critical to Kenya’s fragile economy, was hit hard, with 20 percent fewer visitors in the months following the attack and hopes for hosting future Olympic games and World Cup soccer events dashed. Lax security at one mall sent devastating ripples through an entire national economy and harmed future prospects for development.

Although international terror remains a viable threat to our country, domestic terrorism from right-wing, left-wing, and single-issue groups is perhaps a greater daily concern for our law enforcement agencies. The growing propensity of these organizations and their members to “act out” on soft targets and to step up and engage law enforcement is alarming. The radicalization of Americans continues, with several successful attacks by homegrown jihadists and more than one hundred more thwarted since 9/11 (Crenshaw, Dahl, and Wilson 2017). Exacerbating the threat, the lack of a rehabilitation program means there is no way of ensuring those who serve their prison sentence and return to society will not go back to their old terroristic ways… with a vengeance. Furthermore, the threat of lone actors, already embedded in society and isolated, with unyielding determination, is extremely worrisome. Factor in an unprecedented increase in hate groups and gangs in our country, and the domestic terrorism picture becomes quite grim, with resource-constrained law enforcement agencies struggling to juggle myriad challenges. Finally, brutal Mexican drug trafficking organizations are now operating in the United States; cartels are using gangs to move product and corrupting border patrol officers who open lanes, permitting people and drugs (and potentially worse) into our nation. They are in most every state and are now exploiting rural areas. Cartels use brutal tactics against soft targets in an effort to influence the political process and instill fear in the populace—factors elevating them beyond mere criminal groups. We should expect the same type of horrific violence south of the border to eventually end up on our streets.

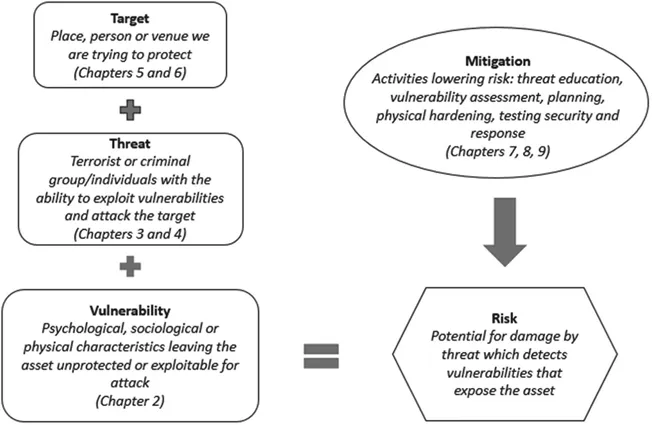

This book remains the first of its kind to explore the topic of soft targeting. The work studies the psychology of soft target attacks, our blind spots and vulnerabilities, and attributes making civilian-centric venues appealing to bad actors. Next, looking through the lens of past, current, and emergent activities, the research yields an estimate of the motivations and capabilities of international and domestic terrorist groups, as well as drug trafficking organizations (arguably terrorists), to hit soft targets in our country. A current assessment of soft target attacks worldwide will give insight to trends and operational tactics and security failures. Studying the activities of terrorist groups, such as ISIS, successfully and repeatedly striking soft targets reveals security vulnerabilities and how poor government engagement and response can intensify the number of casualties. The book explores new tactics and challenges, and the human as the “best weapon system” in this battle. Finally, training and tactics for psychological and infrastructure hardening, as well as planning and exercising strategies, provide a road map for those who own, operate, protect, and use soft target locations.