![]()

1 THE CISO ROAD MAP

![]()

Chapter 1

CISO Role: Evolution or Revolution?

The information security discipline has grown substantially over the past 20 years, evolving into a “profession” previously reserved for technical staff buried deep in the computer operations area. While security controls have been managed since there have been computers, dating back half a century, information security was not a focus area beyond establishing controls for who should have access to the system. The profession has grown substantially in recent years due to the cyber threats, increased connectivity, increased laws and regulations, and a desire to manage security holistically to mitigate the risk of financial loss due to the destruction, loss, or alteration of information.

The need to manage the security of information has given rise to a new role of the CISO, or Chief Information Security Officer. The role is “new” in relation to other industries and roles that have been around much longer. The first named “CISO” was Steve Katz, designated CISO in 1995 for Citibank. While there were individuals named as security managers prior to this time, organizations did not place the value of this role at the executive level. This was the beginning of the environment we know today where it is taken for granted that every organization of any size would have a CISO and even those smaller organizations would have an individual they could name as being accountable for information security.

Other industries such as accounting, construction, and manufacturing processes have been around for many years. For example, the accounting industry dates to Luca Pacioli, who first described the double-entry bookkeeping system used by Venetian merchants. Now those in the information security field may argue that the first information security thinking came from Julius Caesar (100–44 BC), where he created the “Caesar Cipher” substituting each letter of the alphabet with another letter further along. This was used to communicate with his generals and would not be viewed as very strong encryption today, as there were only 25 possible combinations of letters using the displacement. This is where the comparison to early thinking in information security and the accounting profession would stop. While there were advances in information security through such developments as the Enigma machine, first patented in 1919 and used by the German Navy in 1926 used to encipher and decipher messages through a much more complex mechanism than the Julius Cipher, using 17,756 ring settings for each of 60-wheel orders (compared to Julius’s 2-wheel approach), there was still not the concept in organizations of a central person to manage the information security program. Contrast this to the accounting industry, where the industrial revolution necessitated the need for more advanced cost accounting systems and corporations were being formed with bond and stockholders, to the point where the American Association of Public Accountants was formed in 1887 and the first licensed Certified Public Accountants (CPAs) were licensed in 1896. Contrast this with the first broad industry-recognized information security credentialing organization, the International Information System Security Certification Consortium (known as ISC2) formed over 100 years later in 1989. The first credentialed Certified Information Systems Security Professional (CISSP) was issued in 1994, again almost 100 years after the CPA. Today, there are approximately 700,000 CPAs and over 110,000 CISSPs, almost a sevenfold multiple. This short history is essential to understand, as consistency between organizations, public or private sector, does not generally exist as this profession is in an evolution of “best practices” that has had to catch up to the other industries, such as the accounting industry, to standardize practices and generally accepted approaches. This makes the CISO job that much more challenging, as there is the need to review and select the appropriate methods, security frameworks, controls, and policies that will be valuable to the organization they are initiating and leading information security programs.

Clearly, this is a young, maturing industry that has made significant steps in a short period of time. For those that have been in the industry for many years, some days it may feel like the tasks are like those of 20 years ago. This may be true when considering the technical underpinnings are similar—such as the threat environment needs to be evaluated, an organization needs to determine their risk, and controls need to be put in place to mitigate the threats, just as in today’s organizations. The difference between the CISO role today and in the early beginnings has to do with the transformation and maturity of the profession over this period as the attack surface changed, the threat model changed, and the regulatory environment has significantly changed.

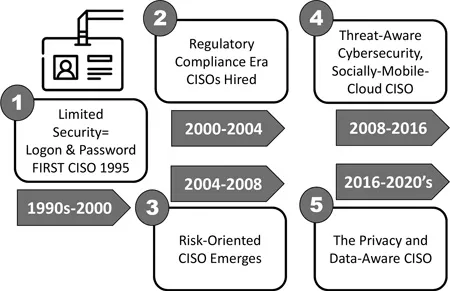

Figure 1.1 Five phases of CISO role evolution 1995–2020. (Adapted from Fitzgerald, Privacy Essentials for Security Professionals, 2018, San Francisco, RSA Conference.)

Understanding how the profession has evolved is instructive to the next-generation CISO to avoid repeating history. The CISO may be the first CISO in an organization or may be the fourth or fifth one in the role. More likely than not, the role of CISO will be something that was created within the last 5–10 years, and the organization may not have much history with the role.

Figure 1.1 illustrates the evolution of the CISO role from 1995 to 2020, depicting the role of the information security profession and the focus of the CISO as continually adapting and expanding. Over the past few decades, I would suggest there have been five distinct phases of information security program maturity, each phase requiring a different focus for the CISO as well as potentially a different type of security leader within the role. Security has been a concern since the beginning of time to keep those away from valuables that were not authorized to have them. The focus changes, and just as we no longer must roll rocks in front of our caves to protect ourselves, we now have other threats to deal with. Knowing the history and how this profession has evolved can be instructive to avoid repeating our previous mistakes or leverage the good ideas from the past. As we work with new technologies, some of the challenges may require new approaches; however, some of the fundamentals of what needs to be in place can leverage some activities of the past.

These stages should be regarded as cumulative or additive in nature. In other words, we expand our breadth as CISOs and the world that needs to be focused on becomes larger in scope.

CISO Phase I: The Limited Security Phase (Pre-2000)

The period prior to 2000 could be considered as the “Limited Security” phase. This is not to imply that organizations did not secure their information assets, but rather that as a formalized discipline that had the board attention of senior management, for most organizations, this was very limited, and in some organizations, nonexistent, compared to today. Financial institutions were clearly ahead of the curve, as there was a real threat to monetary loss if access was gained to the systems. In the 1990s, there was still the perception by many organizations that the information contained within their systems would not be interesting to external parties. Granted, there were firms concerned with intellectual property protection; however, the concern was typically around managing access to ensure that users were properly authenticated and authorized to the systems they needed access to, no more and no less. The focus was on internal logon ID and password provisioning, and physical access. Much of information security was security by obscurity, which today might be referred to as security by absurdity!

So why was the focus so internal for many companies? Much of this had to do with the connectivity of the computer equipment. The 1980s–1990s saw the changeover from “glass house data centers” where all the data was contained within the data center and accessed by terminals, to the introduction of the IBM PC in 1981 connected through local area networks to information. Security controls were necessary to ensure the isolation of human resource and financial systems, as well as to protect the stability of the production environment by implementing processes and controls for change management. Information was also starting to experience data sprawl and proliferation, as desktop computers now contained data previously stored in the data center. Still, the information concern was the flow of information within the organization, along with email to parties outside the organization.

The focus changed from internal protection of access between users to external threats (except for physical threats that were predominantly externally focused) in the mid-1990s as the World Wide Web (www), or the Internet we all take for granted today, was emerging and companies were trying to figure out the appropriate use cases for it. Companies sent questionnaires to employees asking for justification as to why they needed Internet access. This would seem silly today; however, that was the state of the technology in the mid-1990s. It was not until this connection to the Internet that organizations had to start to examine security threats more broadly than the information flow with their business partners (through direct communication links) and external email communications with customers. The Internet presence spawned an entire industry ensuring that firewalls and antivirus (AV) programs were blocking unwanted malicious traffic. On November 2, 1988, Robert Morris, a graduate student in Computer Science at Cornell University, wrote an experimental self-replicating and propagating program called a worm taking advantage of a bug in the Unix sendmail program and let it loose on the Internet. He released the worm from Massachusetts Institute of Technology, so it would not look like it came from Cornell. The worm continued to spread and wreaked havoc before researchers at Harvard, Berkley and Purdue University developed solutions to kill the worm. He was convicted of violating the Computer Fraud and Abuse Act (1986), created to aid law enforcement agencies with the lack of criminal laws to fight the emerging computer crimes. He was sentenced to 3 years’ probation, 400 hours of community service, fined $10,050 (over twice as much in today’s dollars), and the costs of supervision. He appealed, and it was later rejected. This is a small fine in comparison to the estimated damage to the organizations suffering crashes due to the worm, costing universities, military sites, and medical research facilities between $200 and more than $53,000 each to fix. The numbers pale in comparison to the cost of breaches today; however, the impact was large to the organizations connected to the Internet.

As the World Wide Web initiated support for multimedia display in the mid-1990s using HyperText Markup Language along with the common Uniform Record Locaters to simplify address lookup, the Internet became a key technology for organizations to be able to promote their capabilities directly to the end consumer. Along with this new connectivity to the Internet came a new threat vector to organizations outside of the university/research domain—external access beyond email. Firewalls and AV were the panacea to protect the organization from external threats. As CISOs of today like to joke about the good old days, then “as long as you had a firewall and AV,” you were good. Many executives would have that view when it came to security, infrastructure spending for security would end up with limited funding.

The type of leader hired to run the organizations during this period came primarily from a technical background and typically ended up somewhere in the Information Technology (IT) department. In many cases, those running the information security programs were reporting through the computer operations area. Progressive organizations viewed the security of the internal information important and combined the discipline with the database administrators , Data Modelers, software development life cycle practitioners, and systems quality assurance (SQA) testing, placing the security function within information resource management or data management organizations. While this was an important function in larger organizations, the visibility was rarely beyond the IT department. The function was also typically part of someone’s job function, usually as part of a systems administration function or networking function within the IT area. The first CISO role was not named until 1995 (and highlighted by an interview with Steve Katz in this chapter), and the role was not given the high-level visibility except in the largest organizations. The norm was for this role to exist at a manager or director level or at a technical systems administrator level. Rarely would an organization see the need to place this function at a C-level. The Chief Information Officer (CIO) was just emerging in the 1990s as needed with IT becoming a larger impact to organizations; however, the CISO role was just emerging and was not a household word during this period.

STEVE KATZ: INTERVIEW WITH THE FIRST CISO

Executive Advisor Security and Privacy, Deloitte

TODD: Steve we are honored to have you join us today. How did you get into the security field?

STEVE: Thank you Todd. I fell into the information security field accidentally in the 1970s and serendipity is just fantastic! After getting out of school and starting at First National Citibank, I was working in an internal consulting group and was asked to help figure out and be part of the establishment of an SQA function and Systems Development Life Cycle (SDLC) function. We mandated the use of an ID and password module in Cobol and Fortran programs. Although stored in a primitive clear text table, it was the start of protecting the code. I then gained experience when Access Control Facility (ACF2), Resource Access Control Facility (RACF), and Top Secret came on the scene and we converted the programs to use the new security software.

TODD: How popular was the information security group?

STEVE: The security group at that time was as popular as poison ivy, and developers would say, “You want me to do what?” and would blame the security software when application changes would fail. We generally asked them to retest, because it rarely was a problem with the security software.

TODD: What was your experience with auditing security controls in those days?

STEVE: I recall a time when a new examiner, fresh out of school, was sent to audit us. He wrote up a “major issue” in the report sent for my review that there was no “RACF in the DEC VAX” (computing) environment. I let the report go through without comment, and the lead federal examiner from Washington, DC, called and said, “What are you doing over there?” I said, “You are absolutely right—we don’t have RACF in the DEC VAX environment.” He said, “Well, RACF doesn’t run in the DEC VAX environment.” I said, “You are right, next time please send competent examiner!”

TODD: How much information was shared during that period between institutions?

STEVE: In the mid-1980s, the Data/Information Security Officers for the New York banks started getting together on an ad hoc basis every 2–3 months. Every meeting was different, with only two consistent agenda items—when will the next meeting would be held and who was bringing the donuts. This was the forerunner of the Information Sharing and Analysis Centers (ISACs). {Note: Steve was appointed to be the sector coordinator for financial services, following a task force commissioned by President Clinton to examine U.S. critical infrastructure security, holding formation meetings for FS-ISAC in 1997–1999}. We realized if...